Sebasthetops omaliniformis Jäch, 1998

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3635.1.10 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B76B7A06-0744-4510-8738-6A0675F2EFEB |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6155616 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B387BD-FFD7-FFD9-FF28-FE9DA5403A01 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Sebasthetops omaliniformis Jäch, 1998 |

| status |

|

Sebasthetops omaliniformis Jäch, 1998 View in CoL

Material examined. 25/ix/2009, South Africa, Western Cape Province, stream at Mont Rochelle, above Franschhoek. 1,100 m. 7 3 5Ƥ.

Description of male. As female (Jäch, 1998), with the exception of the following characters:

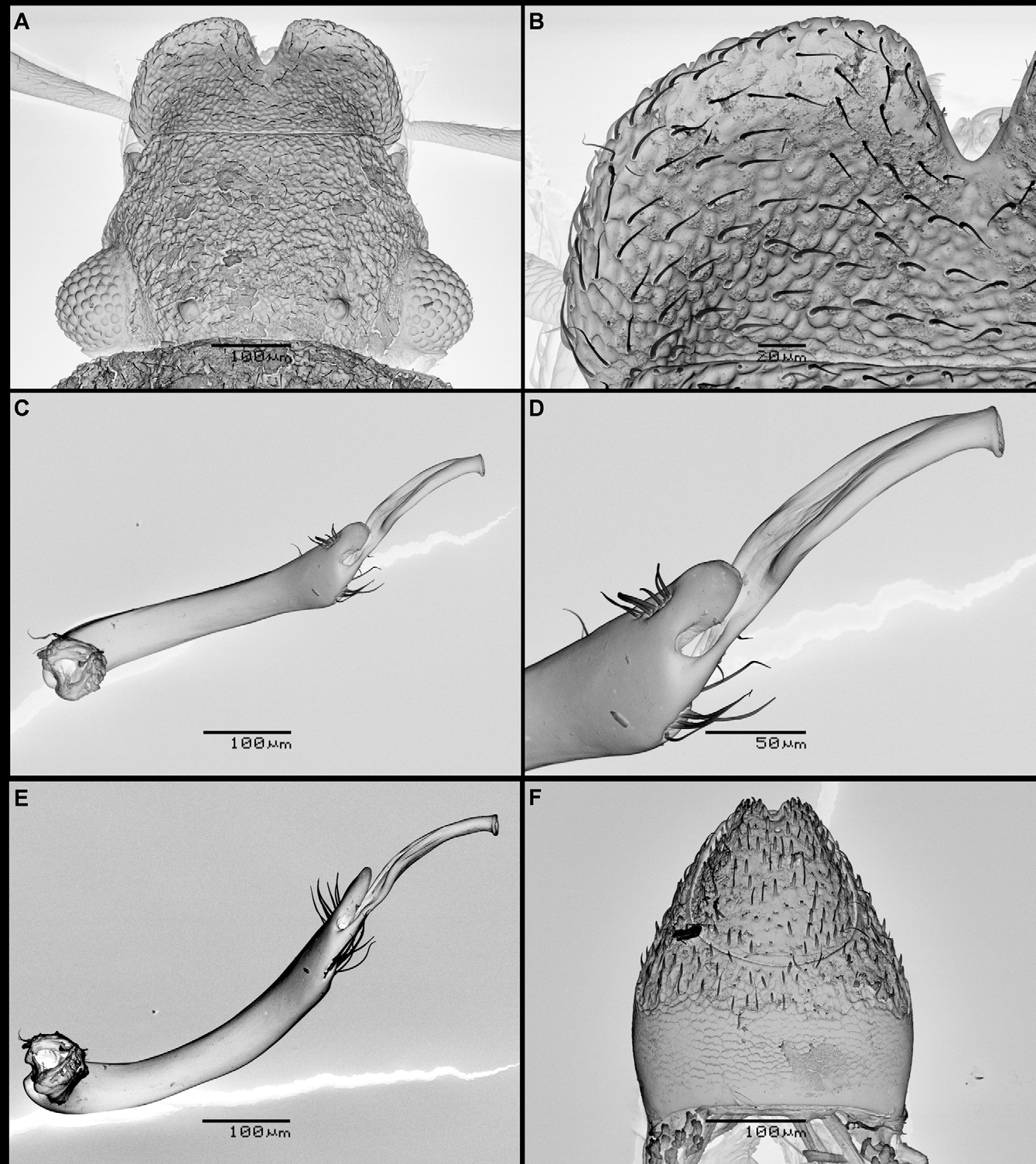

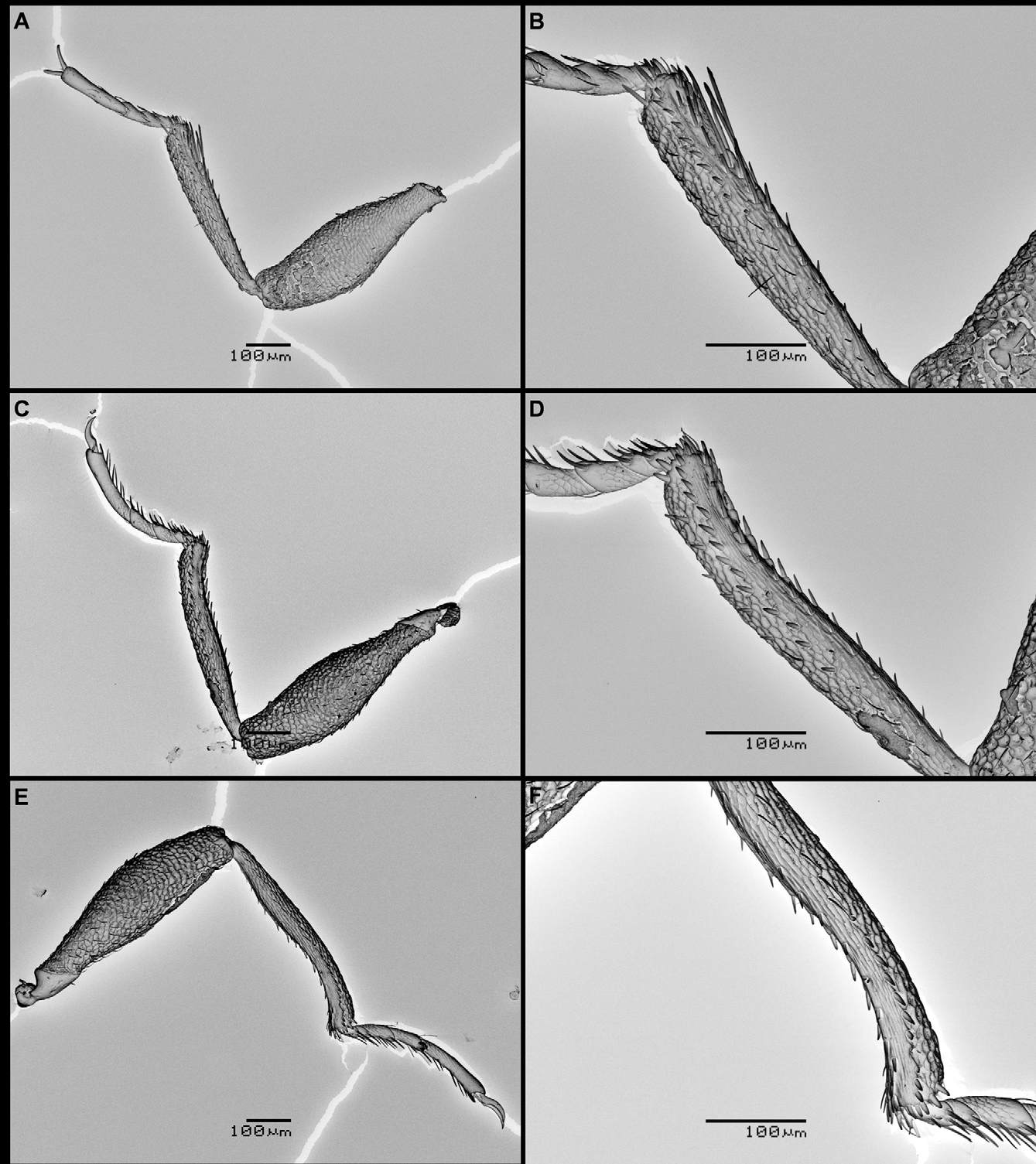

Labrum more elongate, with larger, broader explanate regions at front and outer lateral margins ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 A & B). Maxillary palpi longer, particularly basal and apical segments ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Pronotum narrower and more arched in male; consequently less flattened in appearance. Side margins less strongly toothed ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Elytra much more rounded at sides in dorsal view, and more evenly tapering towards apices, which are much more narrowly truncate ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). More arched in cross section, less flattened than in female, and less serrate at side margins. Elytral ridges less well marked in males, with outer ridge on presumptive interval 8 stronger relative to the others. Granules on elytral intervals larger and more obvious than in females. Elytral pseudoepipleurs as wide as in females, but narrowing in width gradually over their apical third rather than abruptly at apex. As in female, a small portion of tergite VII and tergites VIII–X are exposed. Tergites VII and VIII with dense hydrofuge pubescence; tergites IX and X glabrous. Tergite IX and X with short, stout setae, these being more numerous than in females. Tergite X also differing in shape (see Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 F). Mentum more coarsely rugose than in females. Medial impression of metaventrite deeper, with stronger, deeper punctures. Abdominal sternites II–VII covered in hydrofuge pubescence, and sternites VIII and IX glabrous, as in females. Sternites VIII and IX with fine microreticulation with the exception of a small, smooth shining triangular area at the apex of sternite IX. Sternites VIII and IX with stout bristles; these being stouter and more numerous than those on the abdominal apex of females. Front tibiae with setal fringe occupying 2/3 of inner face ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 A & B); only present in apical ¼ in females, whose setae are also shorter. Mid tibiae ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 C & D) curved and denticulate on inner face, with short, stout spines. Hind tibiae ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 E & F) curved, with bristles and setae on inner face. Mid and hind legs longer than in females. Aedeagus ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 C–E) with stout, evenly curved main piece; parameres entirely absent. Apex main piece with two clusters of setae, and long, flattened distal lobe, with a strong longitudinal furrow and a tubular apex ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 D).

The original description makes no reference to the wings of S. omaliniformis . In all specimens examined, of both sexes (3 3 2 Ƥ), these are very short, approximately 1/3 elytral length, with weak venation, mostly along front margins.

Ecology. All specimens were found under large sandstone rocks resting on a substrate of sandstone cobbles in swift, deep riffles and runs in a nutrient-poor stream flowing through mountain fynbos ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ). Beetles were living in water ca. 60–80 cm deep, and were aggregated and locally abundant on the under surface of larger stones, to which they clung strongly. A wide range of other microhabitats were examined for hydraenid beetles at the time of the visit, but Sebasthetops was apparently restricted to this specific microenvironment. In such places the species was found exclusively in higher reaches of the watercourse, above 1,100 m; lower elevation reaches being apparently devoid of specimens despite superficially suitable microhabitats being present. At Mont Rochelle S. omaliniformis was microsympatric with the elmids Elpidelmis capensis (Grouvelle) , Haplelmis mixta (Grouvelle) , Leielmis cf. georhyssoides (Grouvelle), and Peloriolus spp.

Discussion

Sebasthetops omaliniformis has escaped detection for over twenty years, and is still only known with certainty from a small area of the Dutoitskop mountains above Franschhoek. This is despite targeted sampling of hydraenid beetles in the region, particularly by the late Sebastian Endrödy-Younga, and more recently the present author. Together with the fact that adults have very short wings, clearly incapable of sustaining flight, this strongly suggests that the species has a very narrow geographical range (see Arribas et al., 2011 & Bilton et al, 2001). Aside from the Franschhoek area, the only other specimens of Sebasthetops known are two females collected much further east in the Langeberg [ South Africa: Western Cape Province, Langeberg, Heldersfont, river stones, stop #1565 (20° 52' E; 33° 56' S), elev. 1150 m, coll. Endrödy-Younga, 8 March 1979]. The elytra of these Langeberg specimens are flatter and more markedly acuminate at the apex than material from Franschhoek, however, and in the absence of males it is unclear whether they represent S. omaliniformis or an undescribed species. At Mont Rochelle, S. omaliniformis could only be found in deep, cold areas of fast flowing water, above 1,100 m, and on the basis of present observations the species appears to a be specialized, cold-stenotherm. A number of other Western Cape freshwater invertebrates show similar biogeography and ecology, including species of Syncordulia dragonfly, which are restricted to very small permanent headwater sections of cold mountain streams; some taxa being discovered only recently as a consequence (Djikstra et al., 2007). Such species can be considered relictual, their restriction to high altitude streams likely arising as a consequence of increasing aridity over the course of the Pliocene/Pleistocene (Cowling et al., 2009; Grant & Samways, 2007; Swart et al., 2009).

A number of these biogeographic relicts are also relicts in a phylogenetic sense, being taxonomically isolated or basal within their respective groups. Such cases include southern African Chironomidae with transantarctic affinities, all of which are found exclusively in mountain streams (Saether and Ekrem, 2003) and the water beetle Aspidytes niobe Ribera, Beutel, Balke & Vogler, 2002 , one of only two known members of the family globally (Ribera & Bilton, 2007). Sebasthetops also appears to be phylogenetically isolated, preliminary analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data suggesting that the genus occupies a rather isolated position, sister to a clade containing Mesoceration Janssens, 1967 , Prosthetops Waterhouse, 1879 and related genera (Ribera et al., in prep.). Such ‘evolutionary distinctiveness’ (sensu Isaac et al., 2007; Vane-Wright et al., 1991) clearly adds to the conservation interest of this narrow-range endemic.

At Mont Rochelle Sebasthetops was found exclusively in cold, deep water riffles, under large boulders; a microhabitat not typically occupied by Hydraenidae . Within the family relatively few taxa have successfully penetrated the rithral zone of streams and rivers. In the absence of a well-supported genus-level phylogeny, it is not possible at present to state how many times invasion of this habitat has occurred in hydraenids, but it seems clear that it has happened independently on a number of occasions, including members of the widespread genus Hydraena (particularly the “ Haenydra ” lineage (Hydraeninae—Trizzino et al., 2011)), New Zealand Orchymontiinae (Ordish, 1984; Perkins 1997), many southern African Mesoceration and some Parasthetops ( Prosthetopinae – Perkins & Balfour-Browne, 1994). Within this ecological group of rithral taxa, S. omaliniformis is apparently associated with deep, fast-flowing water, a microhabitat more usually occupied by riffle beetles ( Elmidae ). The dense hydrofuge vestiture on much of the ventral surface of Sebasthetops seems likely to function as an efficient plastron, enabling it to remain submerged indefinitely.

Acknowledgements

Phil Perkins kindly communicated details of the Langeberg material. I am grateful to Rebecca Bilton for her help in the field, and to Prof. Michael Samways, Deon Hignet and Danelle Kleinhans (Cape Nature) for assistance with sampling permits. Pete Bond and Glenn Harper kindly assisted with electron microscopy, and Ignacio Ribera supplied unpublished information on molecular phylogenies.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |