Pedioplanis benguelensis (Bocage, 1867)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5032.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4248D96B-2F99-408C-84EF-26702E02DD1A |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DBD63A-FFBC-CD35-FF17-F89622A328F3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Pedioplanis benguelensis (Bocage, 1867) |

| status |

|

Pedioplanis benguelensis (Bocage, 1867) View in CoL

( Figs. 2–4 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 )

Eremias Benguellensis: Bocage (1867a: 221) View in CoL

Eremias benguelensis: Bocage (1867b: 229) View in CoL

Eremias namaquensis: Boulenger (1887: 91) View in CoL [part]; Bocage (1895: 31) [part]

Eremias undata: Boulenger (1921: 283) [part]

Pedioplanis sp. 1 : Conradie et al. (2012b: 95)

Pedioplanis benguellensis: Ceríaco et al. (2016: 56) View Cited Treatment [part]; Marques et al. (2018: 222) [part]; Branch et al. (2019b: 92; 2019c: 306) [part]

Bocage (1867a) briefly mentioned three specimens of a new species “ Eremias benguellensis ”, collected by Anchieta in “Benguella” [= Benguela, Benguela Province], referring to a “diagnosis elsewhere”. In a subsequent paper that appeared immediately after in the same issue of the Jornal de Sciencias Mathematicas, Physicas e Naturaes, Bocage (1867b) provided a morphological description of “ Eremias benguelensis ”, spelling the specific epithet with a single “l”. The correct spelling of the name “ benguelensis ” has not been established to date, with both spellings being used by different authors over the years. The lack of a diagnosis in Bocage’s (1867a) first paper could lead one to consider it a nomen nudum under Article 12 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, however, the fact that both papers were simultaneously published in the same issue raises ambiguity. Considering this, the Principle of the First Reviser should be applied and, therefore, under Article 24.2 of the Code, Boulenger (1887) would act as First Reviser and establish “ benguelensis ” as the valid spelling.

In the morphological description of Eremias benguelensis, Bocage (1867b) seemingly describes only one specimen and makes no reference to a type series, even though he provides a range of ventral scales. In an annotated type catalogue of the lacertids in the Museum für Naturkunde (ZMB), Berlin, Germany, Bauer & Günther (1995) note that the ZMB catalogue lists a syntype (ZMB 7762) of Eremias benguelensis collected in “Maconjo” and donated by Bocage, which could not be located by the authors and was considered lost. The locality “Maconjo” could not be located by Bauer & Günther (1995) and has been tentatively interpreted as “Fazenda Mucungo, Namibe Province ” by Marques et al. (2018). However, Vaz Pinto et al. (2019) noted the existence of two historical collecting localities bearing the name “Maconjo” in Angola: one near Capangombe in Namibe Province, where Anchieta was known to collect; and another in Benguela Province, visited by William John Ansorge between 1903 and 1905, that these authors restricted to the “vicinity of the streams Conjo, Conjo Pequeno, and Cocumba (12º52’S, 13º21’E, 355 m asl), 20 km south of Uche, Benguela Province ” ( Vaz Pinto et al. 2019). Considering this, if a specimen bearing the locality “Maconjo” was indeed donated by Bocage to the ZMB, it most likely would have been collected by Anchieta in Namibe Province, near Capangombe. However, this specimen could not have been part of the original type series, as the description of Eremias benguelensis was published before Anchieta sent the first batch of specimens from Maconjo to Bocage in early October 1867 ( Banha de Andrade 1985), and reference to that specific locality was only made in Bocage (1873). Nevertheless, this putative syntype has not since been located in the ZMB collections ( Bauer & Günther 1995; LMPC pers. obs.) and its status could not be verified.

Boulenger (1887) referred E. benguelensis to the synonymy of E. namaquensis without providing any justification or record of Angolan specimens, and this was followed by Bocage (1895), who referred his previous records to the synonymy of this species. However, Bocage’s (1895) interpretation of “ namaquensis ” could have included up to three distinct taxa, as his material at hand comprised specimens from “Benguella” and “Catumbella”, which likely represented true P. benguelensis , and specimens from “l’intérieur de Mossamedes” and “Capangombe”, which probably represented a different taxon. Except for a specimen collected by Anchieta in Capangombe (MHNCUP/ REP 0231, Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 , see below), this material was lost in the fire that engulfed and destroyed all the collections of Museu Bocage in 1978 ( Marques et al. 2018), making it impossible to ascertain the taxonomic identity of these specimens.

Based on material collected by Ansorge and deposited in the collections of the BMNH, Boulenger was the first author to recognize the existence of two distinct species in Angola, recovering E. benguelensis as a valid species, diagnosed by the presence of a “large transparent disc formed of a single black-edged scale” on the lower eyelid ( Boulenger 1918), and assigning specimens characterized by a “lower eyelid with a transparent disc formed of 2 (…) larger black-edged scales”, from “Maconjo” and “Huxe”, in Benguela Province, to Eremias undata ( Boulenger 1921) . However, even though Bocage (1867b) mentioned a “transparent disc” on the lower eyelid, he did not mention the number of scales it comprised. The interpretation of this character can be ambiguous, considering that Bocage might have ignored the taxonomic value of this character, as did Laurent (1964) when he included both specimens with one and two transparent scales on the lower eyelid in the material he assigned to Eremias undata . Additional specimens conforming to Boulenger’s (1921) description of E. undata were collected by Wulf Haacke in Benguela and Namibe provinces during the 1970s and are deposited in the collections of the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History. Specimens conforming to Boulenger’s (1921) description of Eremias undata , with two transparent scales on the lower eyelid, were also collected by Conradie et al (2012b). Boulenger’s (1918, 1921) diagnosis of E. benguelensis based on the condition of the lower eyelid was accepted by subsequent authors (e.g., Parker 1936; Monard 1937; Mertens 1971; Szczerbak 1975; Mayer 1989; Arnold 1991; Branch 1998), leading Conradie et al. (2012b) to assign newly collected material from Namibe Province to this species.

During recent surveys, additional material was collected in the coastal areas of Benguela Province, in the vicinity of the original type locality of “Benguella”, which allowed for a reassessment of the status and diagnosis of P. benguelensis . As the original type material was lost in the fire that destroyed the collections of Museu Bocage on 18 March 1978, and the putative syntype identified by Bauer & Günther (1995) could not be located in the ZMB collections, the allocation of the name P. benguelensis to a specific taxonomic unit within the various lineages of Angolan Pedioplanis remains problematic. This situation is exacerbated by the lack of details provided by Bocage (1867a, 1867b) in the original descriptions, and the differences in subsequent interpretations by Boulenger (1887, 1918, 1921), Bocage (1895), Laurent (1964) and Conradie et al. (2012b). For the purpose of taxonomic and nomenclatural stability we consider it necessary to designate a neotype for this species.

Our results indicate that at least two species of Pedioplanis occur near Benguela, and Bocage’s (1867b) vague description could apply to either of them. The only known surviving specimen that was presumably examined by Bocage (MHNCUP/REP 0231) has a single transparent scale on the lower eyelid, agreeing with Boulenger’s (1918, 1921) diagnosis of P. benguelensis . However, while the material cited by Bocage (1867a) from Benguela was shipped by Anchieta in September 1866, the first batch of specimens from Capangombe was only shipped in July 1867 and reptiles from this locality were only cited in Bocage (1873). Therefore, this specimen could not have been part of the original type series, and was never unambiguously referred to P. benguelensis . Furthermore, it is likely that Bocage’s (1867a) original material comprised more than one taxon, and Boulenger’s (1918, 1921) decision to allocate the name P. benguelensis to his specimens with a single transparent scale on the lower eyelid was based on his own interpretation of Bocage’s vague description, as we found no evidence suggesting that he ever examined Bocage’s original material.

Instead of being consistent with Boulenger’s (1918, 1921) interpretation, we believe Bocage’s (1867b) original description of coloration—“ligne médiane d’une raie longitudinale noiratre (…) De chaque côté de cette raie dorsale une autre raie plus large noire, bordée en dessou de blanc”—is the most informative portion of his description and is more consistent with the coastal populations with two transparent scales on the lower eyelid, treated by Boulenger (1921) as Eremias undata . While these specimens display three distinct and well-defined dark dorsal stripes (see Diagnosis below), those with a single transparent scale on the lower eyelid most often show an indistinct vertebral stripe and broken dorsolateral stripes (see description below). Furthermore, we considered the proximity to the type locality as a main factor for the name allocation decision. Even though both species are sympatric in the vicinity of Benguela, what we designate as P. benguelensis sensu stricto has a coastal distribution centered in Benguela, while P. benguelensis sensu Boulenger (1918, 1921 ) is widely distributed in inland Benguela and Namibe provinces, with records from the coastal areas being scarce. Considering that Anchieta’s first exploration of Benguela was mostly limited to coastal areas ( Banha de Andrade 1985), we believe that he would be more likely to have collected the former rather than the latter. A designation of a neotype for Pedioplanis benguelensis (Bocage 1867) and an updated diagnosis for the species are provided below.

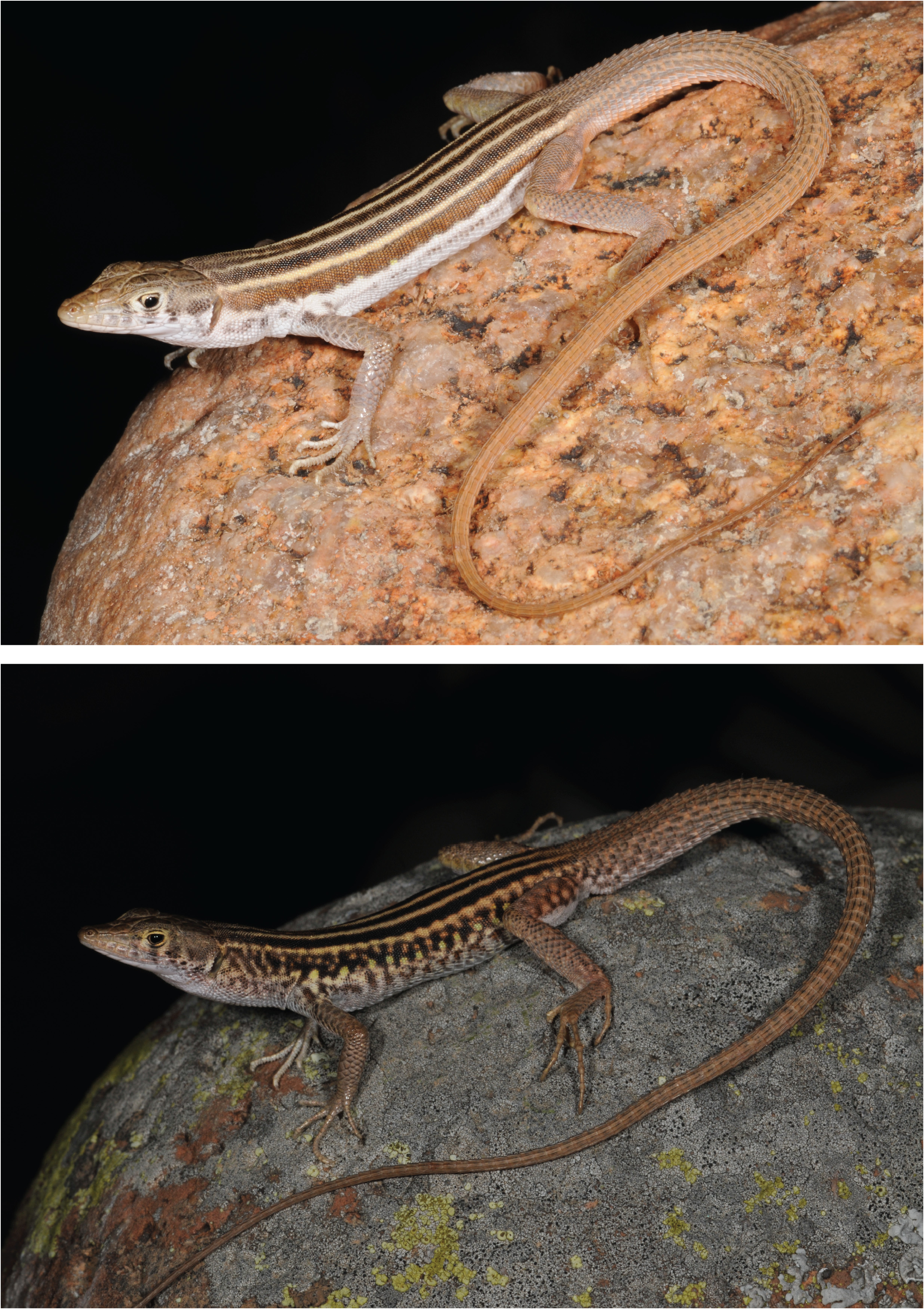

Diagnosis. Pedioplanis benguelensis is a boldly striped and medium-sized Sand Lizard, with an average SVL of 48 mm (max 58 mm) and a tail roughly two and a half times the SVL ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ). It can be distinguished from other species of the genus in Angola and Namibia by the following combination of characters: (1) lower eyelid with two enlarged transparent scales (rarely one—PEM R24110, or three—CAS 266239), with two to four smaller ones below; (2) five (rarely four or six) supralabials anterior to the subocular and usually three posteriorly; (3) two (sometimes one or three) rows of small granules between the supraoculars and supraciliaries; (4) a group of 9–26 (> 13 in 75% of specimens) small granules preceding the supraoculars; (5) ventral scales in ten longitudinal rows; (6) presence of three bold black stripes extending from the back of the head to the base of the tail. The background coloration of the dorsum is brownish, with black stripes intercalated with thinner yellowish lines. The vertebral stripe splits at the neck, and in rare cases may be entirely divided into two thinner lines. Dorsolateral stripes are bold and welldefined. On the flanks there is a dark lateral stripe that starts behind the eye and extends to the hindlimb insertion, usually faint and reticulated, and often with a series of yellow spots along its lower edge. There may also be a thin and irregular line or series of streaks of reddish to black coloration, starting behind the labials and extending to the hindlimb insertion. The hindlimbs and the tail are greyish to reddish brown, with the legs often covered above by more or less distinct pale circles surrounded by dark pigmentation. The underparts are white, sometimes reddish at the base of the tail and hindlimbs.

Comparison with other Pedioplanis species. Pedioplanis benguelensis is readily distinguished from P. burchelli , P. laticeps , P. breviceps (Sternfeld, 1911) , P. namaquensis and P. husabensis by the presence of two enlarged transparent scales on the lower eyelid (versus eight or more opaque to semi-transparent scales in the remaining species); from P. lineoocellata (Duméril & Bibron, 1839) by the presence of an enlarged tympanic shield (versus no enlarged tympanic shield in P. lineoocellata ); from P. inornata , P. rubens , P. gaerdesi and P. branchi by the presence of distinct dorsal stripes (versus no stripes in P. inornata , P. rubens , P. gaerdesi and P. branchi ); and from P. undata by a higher number of granules anterior to the supraoculars (usually> 13 in P. benguelensis versus <14 in P. undata ). Pedioplanis benguelensis is identical in most morphological characters to P. mayeri , from which it can be distinguished based on a greater maximum number of granules anterior to the supraocular (9–26 in P. benguelensis versus 9–16 in P. mayeri ) and geographic location ( P. benguelensis restricted to Angola versus P. mayeri restricted to Namibia). Regarding Angolan congeners, P. benguelensis is distinguished from P. haackei by dorsal color pattern (dark stripes distinct all the way to the tail in P. benguelensis versus mostly fading posteriorly in P. haackei ); and from P. huntleyi by a higher number of granules anterior to the supraoculars (usually> 13 in P. benguelensis versus <12 in P. huntleyi ), usually two rows of granules between supraoculars and supraciliaries (versus usually one in P. huntleyi ) and dorsal color pattern (dark stripes distinct all the way to the tail in P. benguelensis versus faded posteriorly in P. huntleyi ). It is distinguished from an undescribed species by the presence of two enlarged transparent scales on the lower eyelid (versus one, see description below).

Neotype. CAS 266242 About CAS (field number AMB 9984 View Materials ; Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ), adult male from Chimalavera Nature Reserve, vicinity of Main Camp [-12.83377°, 13.16991°, 293 m], Benguela Province. Collected by Luis M.P. Ceríaco, David C. Blackburn and Aaron M. Bauer on 11 December 2015. This specimen was selected as neotype because it was collected in the same biogeographic region and in the vicinity of the original type locality (<35 km distant), has associated genetic data, and its morphological characters closely match the original description.

Additional material. 49 specimens: Benguela Province: 5 km inland from Meva beach [-13.47778°, 12.59222°, 244 m] ( PEM R 24225) ; Chimalavera Nature Reserve, vicinity of Main Camp [-12.83377°, 13.16991°, 293 m] ( CAS 266237 About CAS *–266241*, 266243*–266246*) ; Dombe Grande-Cuio road [-12.97805°, 13.07391°, 130 m] ( CAS 266247 About CAS *) ; pass into Meva Bay [-13.42278°, 12.57083°, 103 m] ( PEM R 24101, 24102 View Materials ) ; near Benguela [-12.63556°, 13.31500°, 64 m] ( PEM R 22070) ; road to Benguela, S of Dombe Grande [-13.02000°, 13.08806°, 280 m] ( PEM R 24741, 24742 View Materials ) ; small canyon near Meva fishing village [-13.41556°, 12.57639°, 30 m] ( PEM R 24110*, 24111, 27735, 27736) ; 10 km N of Lobito [-12.33478°, 13.65085°, 301 m] ( TM 46575 ) ; 35 km S of Dombe Grande [- 13.27569°, 12.94866°, 362 m] ( TM 41254 ) ; Cimo, Equimina River [-13.333333°, 12.933333°, 268 m] ( TM 41245 ) ; Cuanza-Sul Province: Sumbe [-11.20026°, 13.84186°, 11 m] ( PEM R 25195*, 25196*) ; Namibe Province: 10.4 km S of Makonga River, on tar road to Bentiaba [-14.84194°, 12.427778°, 370 m] ( PEM R 24209, 24210 View Materials ) ; 10 km SE of Lucira [-13.93139°, 12.59444°, 546 m] ( PEM R 24076*) ; road to Bentiaba, 25 km N of junction with Lubango-Namibe road [-14.85292°, 12.42481°, 430 m] ( PEM R 21665*, 21666*) ; sand road towards Chapeu Armando [-14.51972°, 12.44028°, 471 m] ( PEM R 24147) ; 2 km S of Chapéu Armado [-14.46917°, 12.33750°, 23 m] ( PEM R 24138) ; Mucungo farm [-14.79528°, 12.49500°, 342 m] ( PEM R 24142*) , [-14.77890°, 12.48745°, 305 m] ( CAS 266250 About CAS ) ; Bentiaba Fort [-14.27329°, 12.38505°, 51 m] ( CAS 266254 About CAS ) ; dirt tracks N of Moçâmedes [-14.93503°, 12.26406°, 167 m] ( PEM R 21648*–21650*) ; small ridges N of Moçâmedes [-14.92408°, 12.37192°, 314 m] ( PEM R 21651*, 21652*) ; 31.5 km E of Namibe [-15.01686°, 12.39003°, 310 m] ( PEM R 18540*) ; 12 km S of Bentiaba [-14.34642°, 12.41838°, 248 m] ( TM 41148 , 41149 ) ; Bentiaba [-14.26667°, 12.38333°, 11 m] ( TM 25464 ) ; Lucira [-13.86667°, 12.53333°, 51 m] ( TM 41191 ) ; Lucira road, 5 km S of Catara River [-13.60194°, 12.62888°, 331 m] ( TM 41198 , 41201 , 41229 ) ; coastal tracks 11 km N of Namibe, 1 km before old bridge across Giraul River [- 15.08906°, 12.17014°, 58 m] ( PEM R 21658*) .

The following specimens were tentatively assigned to this species based on a combination of morphological characters and geographic location (11 specimens): Benguela Province: Cimo, Equimina River [-13.33333°, 12.93333°, 268 m] ( TM 41244 ) ; Namibe Province: 10 km SE of Lucira [-13.93139°, 12.59444°, 546 m] ( PEM R 24077) ; road to Bentiaba , 5 km S of Makonga River [-14.79750°, 12.43389°, 394 m] ( PEM R 24216, 24217 View Materials ) ; 2 km S of Chapéu Armado [-14.46917°, 12.33750°, 23 m] ( PEM R 24139) ; 2 km inland from Mucuio Bay [-14.89611°, 12.23722°, 110 m] ( PEM R 24155) ; Bentiaba [-14.26667°, 12.38333°, 11 m] ( TM 25466 , 43965 ) ; Lucira road, 5 km S of Catara River [-13.60194°, 12.62888°, 331 m] ( TM 41228 , 41232 , 41233 ) .

Description of the Neotype. The neotype is an adult male with a complete original tail ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ). SVL 57.4 mm; TL 144.1 mm. Body relatively stout (SVL/HL 4.35), with hindlimbs longer than forelimbs and tail length two and a half times the SVL (TL/SVL 2.51). Moderately sized head (HL/SVL 0.23), distinct from the neck. Other relevant measurements are presented in Table 5. Rostral wider than high, visible from above. Nostril pierced between three scales; supranasals slightly swollen and in broad contact with each other behind rostral; infranasal in contact with rostral, first supralabial and anterior loreal; postnasal small and subquadrangular, placed between the supranasal, infranasal, anterior loreal and frontonasal. Frontonasal slightly longer than wide, rounded anteriorly and slightly acuminate posteriorly. Prefrontals in broad contact with each other, the loreals, frontonasal and frontal. Two loreals, posterior largest. Frontal longer than wide, narrower posteriorly, in contact with prefrontals anteriorly, supraoculars laterally and frontoparietals posteriorly. Paired frontoparietals in broad median contact, touching the frontal and posterior supraocular anteriorly, and the parietals and interparietal posteriorly. Interparietal pentagonal, longer than broad. Occipital small, wider than long, in broad contact with interparietal, its posterior margin slightly wider than the anterior. Parietals longer than wide, in contact with frontoparietals, interparietal and occipital. Two rounded supraoculars in contact with each other and the frontal, preceded by a group of 14 (right side) and 13 (left side) small granules, those in contact with the frontal and prefrontal largest. Two rows of small granules between supraoculars and supraciliaries. Supraciliaries six (right side) and seven (left side), first longest. Temporal scales small and granular. One narrow and elongated tympanic shield at the anterodorsal edge of ear opening. Subocular bordering lip, upper margin wider than lower. Five supralabials anterior to subocular and three posteriorly. Lower eyelid with two black edged, enlarged transparent scales, with two smaller ones below. Infralabials six. Mental wider than long, in contact with first infralabials and first pair of chin shields. Four pairs of chin shields, first three in median contact and fourth largest. Gular scales 31, in a straight line between the symphysis of the chin shields and median collar plate. Collar free, comprising seven enlarged plates. Ventral scales smooth, in ten longitudinal and 28 transverse rows; outer scales smaller than others; those on the first complete transverse row posterior to collar notably longer than others. Precloacal scales irregular and subequal, central ones largest. Fifteen femoral pores on each leg. Lamellae under fourth toe 27. Dorsal scales small and granular, larger towards ventral scales. Upper forelimbs covered above by large hexagonal plates; forearm covered above by slightly imbricate and keeled scales, larger than dorsal scales, and below by enlarged plates. Hindlimbs covered above by slightly imbricate and keeled scales, larger than dorsal scales, and below by enlarged plates. Scales on tail diagonally keeled, except for those on ventral side of basal portion, which are smooth.

Coloration (in preservative). Head and limbs brownish; hindlimbs covered above with pale circles surrounded by black speckling. Dorsum with three bold and well-defined dark stripes intercalated with four thinner white to yellowish lines, extending from the back of the head to the base of the tail. The black vertebral stripe splits at the nape towards parietals. Flanks with a reticulated black stripe extending from the back of the eye to the hindlimb insertion, with a series of pale spots running along its lower edge. Tail brown above, with some black keeled scales. Moderate greyish speckling on the labials and flanks. Venter white.

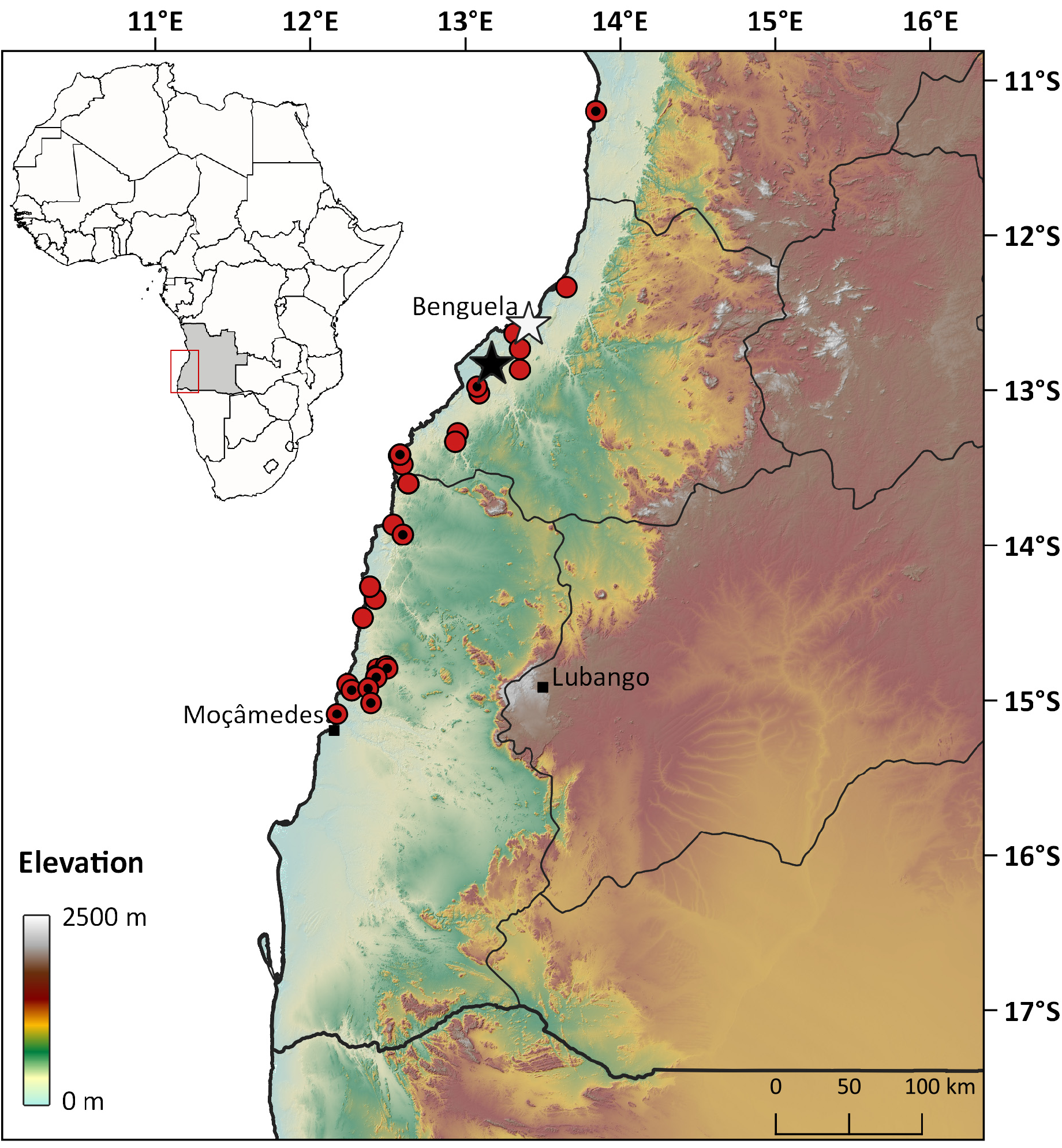

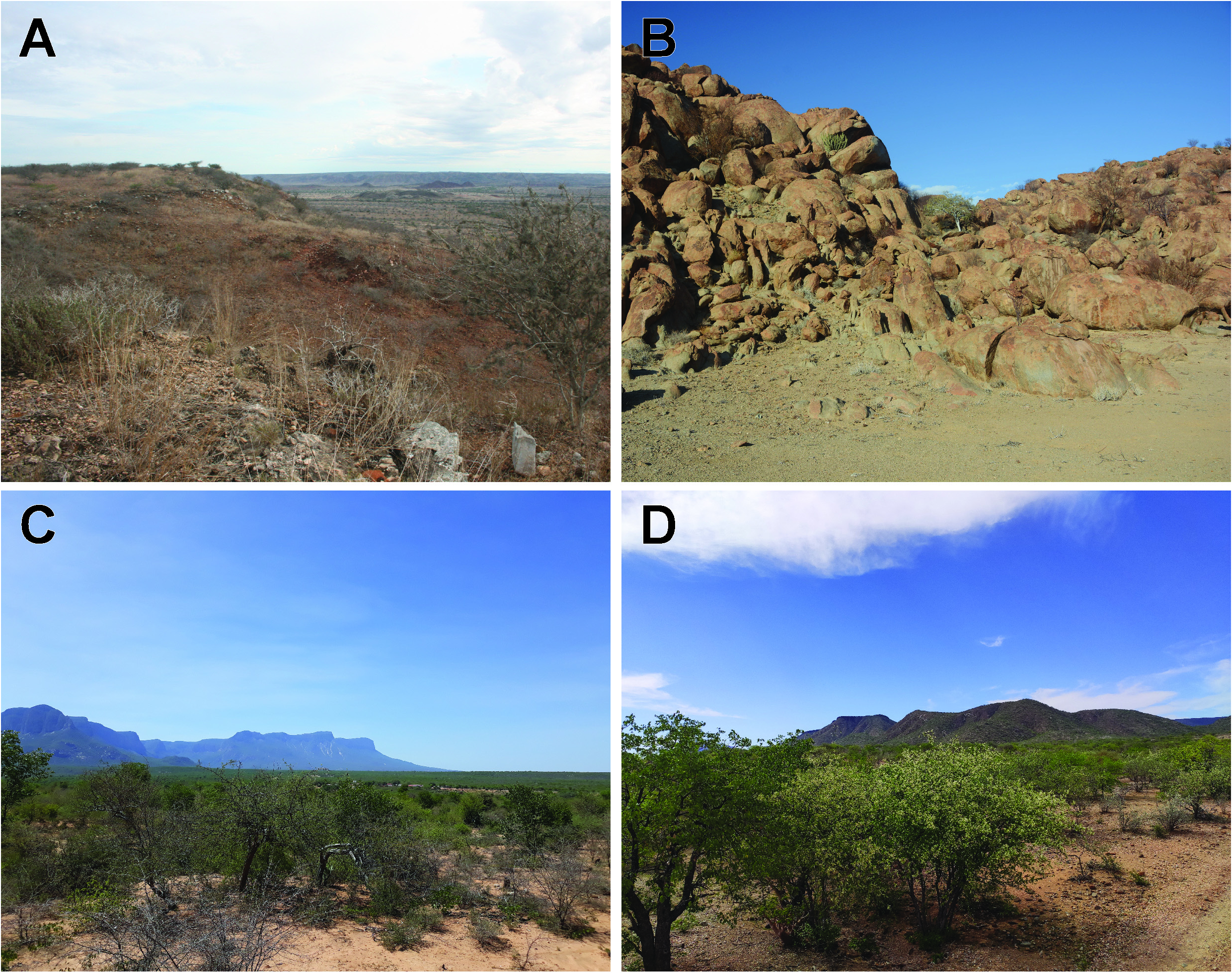

Distribution and habitat. Known records of P. benguelensis are restricted to lower elevation areas (below 546 m) in coastal Angola, as far as 30 km inland from the coastline, from Moçâmedes, Namibe Province, northwards to Sumbe, Cuanza-Sul Province ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ). It is sympatric with an undescribed species in most of coastal Benguela Province and northern Namibe Province, and P. haackei in the littoral of northern Namibe Province. This species inhabits the xeric coastal areas of southwestern Angola, which are characterized by sublittoral steppes with bushes and herbage, mostly belonging to the plant genera Senegalia, Commiphora , Colophospermum , Aristida , Schmidtia and Setaria ( Grandvaux-Barbosa 1970; Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

| PEM |

Port Elizabeth Museum |

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pedioplanis benguelensis (Bocage, 1867)

| Parrinha, Diogo, Marques, Mariana P., Heinicke, Matthew P., Khalid, Farkhanda, Parker, Kelly L., Tolley, Krystal A., Childers, Jackie L., Conradie, Werner, Bauer, Aaron M. & Ceríaco, Luis M. P. 2021 |

Pedioplanis benguellensis: Ceríaco et al. (2016: 56)

| Branch, W. R. & Conradie, W. & Vaz Pinto, P. & Tolley, K. A. 2019: 92 |

| Branch, W. R. & Vaz Pinto, P. & Baptista, N. & Conradie, W. 2019: 306 |

| Marques, M. P. & Ceriaco, L. M. P. & Blackburn, D. C. & Bauer, A. M. 2018: 222 |

| Ceriaco, L. M. P. & Sa, S. A. C. & Bandeira, S. & Valerio, H. & Stanley, E. L. & Kuhn, A. L. & Marques, M. P. & Vindum, J. V. & Blackburn, D. C. & Bauer, A. M. 2016: ) |

Pedioplanis sp. 1

| Conradie, W. & Measey, G. J. & Branch, W. R. & Tolley, K. A. 2012: 95 |

Eremias undata:

| Boulenger, G. A. 1921: ) |

Eremias namaquensis: Boulenger (1887: 91)

| Bocage, JVB 1895: 31 |

| Boulenger, G. A. 1887: ) |

Eremias Benguellensis: Bocage (1867a: 221)

| Bocage, J. V. B. 1867: ) |

Eremias benguelensis: Bocage (1867b: 229)

| Bocage, J. V. B. 1867: ) |