Otospermophilus douglasii ( Richardson, 1829 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1093/mspecies/sead010 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4D24F4D5-E4C3-4606-879D-4985392A35D4 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BC2FC613-FF9C-CB5E-FF44-B135FE2E1836 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Otospermophilus douglasii ( Richardson, 1829 ) |

| status |

|

Otospermophilus douglasii ( Richardson, 1829)

Douglas Ground Squirrel

Arctomys View in CoL ? ( Spermophilus View in CoL ?) Douglasii Richardson, 1829 , 1:172. Type locality “banks of the Columbia,” (see “Nomenclatural Notes”).

Spermophilus douglasii : Cuvier, 1831:333. Name combination.

Spermophilus grammurus var. Douglasi Allen, 1874:293. Name combination and incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Spermophilus grammurus douglassi : Bryant, 1891:355. Name combination and incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Spermophilus (Otospermophilus) grammurus douglasi : Elliot, 1901:89. Name combination and incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Citellus View in CoL v [ariegatus]. douglasi : Elliot, 1903:183. Name combination and incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Citellus beecheyi douglasi : Grinnell, 1913:345. Name combination and incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Citellus douglasii : Grinnell, 1918:644. Name combination. Citellus douglasi : Couch, 1922:18. Incorrect subsequent spelling of douglasii ( Richardson, 1829) .

Otospermophilus grammurus douglasii : Miller, 1924:181 Name combination.

Otospermophilus douglasii : Edge, 1931:194. First use of current name combination.

CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Rodentia, suborder Sciuromorpha, family Sciuridae, tribe Marmotini ( Howell 1938; Hall 1981; Helgen et al. 2009). Eight subspecies of Otospermophilus beecheyi were recognized by Hall (1981), Helgen et al. (2009), Howell (1938), Thorington and Hoffmann (2005). However, recent genetic studies supported the elevation of O. b. douglasii to full species status as O. douglasii ( Phuong et al. 2014). Thus, the three species of Otospermophilus are: O. douglasii ( Richardson, 1829); O. beecheyi ( Richardson, 1829); and O. variegatus ( Erxleben, 1777). To reflect this, we have made every effort to include only information on O. douglasii (formerly O. b. douglasii) from older literature, as well as references to O. beecheyi from the known range of O. douglasii. Our revised distribution for O. beecheyi follows the traditional subspecific distribution of O. beecheyi from previous workers, with the Sacramento River assumed to be the biogeographic barrier between O. douglasii and O. beecheyi. Otospermophilus douglasii is located west and north, whereas O. beecheyi is east and south of the Sacramento River ( Grinnell and Dixon 1918; Grinnell 1933; Howell 1938; Hall 1981). Recent genetic studies support the Sacramento River as the polyphyletic division between O. douglasii and O. beecheyi ( Phuong et al. 2014; Holding et al. 2021). However, the precise taxonomic delineation of Otospermophilus living in southeastern Yolo and Solano counties, along the northwestern margin of the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, remains unclear ( Phuong et al. 2014). Moreover, while there is apparently no overlap of O. douglasii and subspecies of O. beecheyi ( Grinnell and Dixon 1918; Grinnell 1933), laboratory experiments showed that captive O. douglasii can hybridize with both O. b. beecheyi to the south and O. b. fisheri to the east ( Marsh and Howard 1968), so precise delineation of species ranges, whether a clear species boundary or a hybrid zone, has not yet been genetically determined. Given this current uncertainty, we have included some information about those conspecifics but have noted their county of origin.

NOMENCLATURAL NOTES. Formerly placed in Spermophilus as one of the subspecies of S. beecheyi, this species was reclassified as O. beecheyi douglasii in the genus Otospermophilus ( Helgen et al. 2009). Otospermophilus is a name derived from Greek and attributed to the relatively large ears and its dietary preference for eating seeds. Specifically, “ Otos ” means ear, “ spermatos ” means seed, and “ phileo ” means love ( Jaegar 1955). Otospermophilus is a sister lineage of Callospermophilus ( Harrison et al. 2003; Helgen et al. 2009). Higher-level taxonomy follows Helgen et al. (2009), and the species designation as O. douglasii follows Phuong et al. (2014).

The type specimen was collected by Scottish botanist David Douglas, who received a skin from a hunter on the “banks of the Columbia ” during one of his three explorations in western North America aboard the HMS Blossom. Grinnell and Dixon (1918:644) stated, without any evidence, the type locality to be “ Probably somewhere in southern Oregon or northern California. ” This was despite Richardson (1829:172) stating that the type specimen was collected “from the banks of the Columbia.” Given that O. douglasii was absent from southwestern Washington state at the time of Grinnell and Dixon’s (1918) statement, the type specimen was most likely instead taken from the mouth of the Columbia River near the Pacific Ocean in the vicinity of the northwestern coast. This area is now Fort Stevens State Park in Oregon. Dalquest (1948:276) stated that the type locality was “probably near The Dalles, Wasco County, Oregon,” though Lyman (1909) clearly explains that the HMS Blossom did not sail east of Fort George (now Fort Astoria) in the Columbia River mouth. The common name, the Douglas ground squirrel, was resurrected, following the use of that name in many earlier works; this was true despite possible confusion with the Douglas squirrel, Tamiasciurus douglasii , a tree squirrel found from northern California to British Columbia, also named in honor of botanist David Douglas ( Steele 1999).

DIAGNOSIS

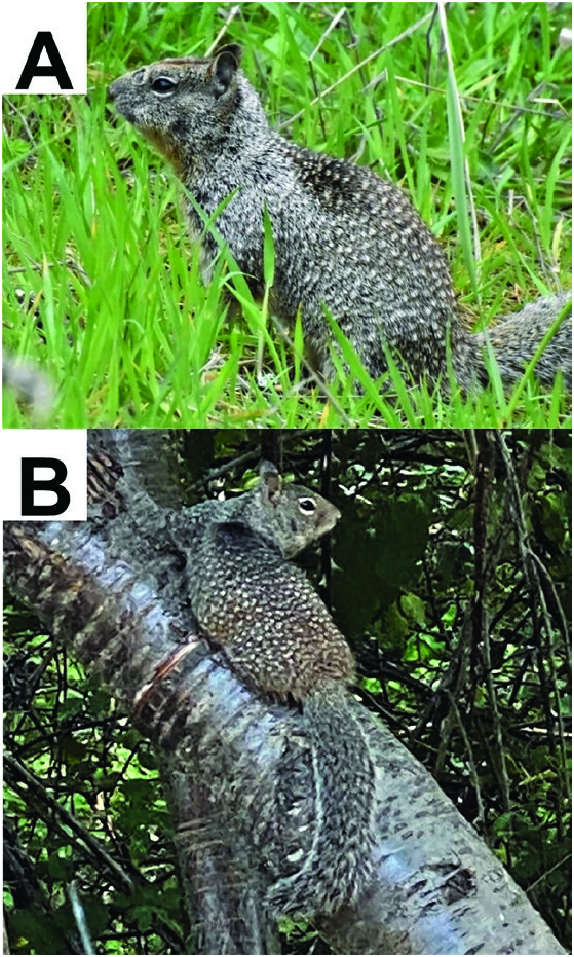

Compared to ground squirrels of other genera, the distinguishing traits of Otospermophilus douglasii include ventral fur that is light brown to cream-colored, a long, bushy tail, and white rings around the eyes ( Eder and Ross 2005). Despite their similar color variation, the medial stripe of O. douglasii is darker than that of O. beecheyi ( Allen 1874) . The charcoal to blackish-brown triangular patch extending from the nape of neck to about midway down the back, the lighter colored brown shoulders, and the dense, silvery hairs that are often present on the lateral margins of the nape and the shoulders are the major characteristics that distinguish O. douglasii from O. beecheyi . The upper forelegs and tail of O. douglasii typically have lateral hairs tipped with white; this contrasts with the buffy wash seen on the lateral hairs in O. beecheyi . These differences between O. douglasii and O. beecheyi are most apparent in adults and may not be as discernable in immature individuals ( Allen 1874; Thorington et al. 2012). The grayish brown fur with speckled white spots on the dorsum of O. douglasii distinguishes it from O. variegatus , the rock squirrel. Specifically, in addition to having grayish brown fur, the dorsum of O. variegatus typically includes a mixture of cinnamon buff and light brown to bone to dark blackish-brown fur ( Thorington et al. 2012). In some instances, the entire dorsum of O. variegatus is black, a feature that is absent from O. douglasii ( Thorington et al. 2012) .

GENERAL CHARACTERS

The pelage of Otospermophilus douglasii is sandy-brown to grayish brown dorsally and laterally with a scattering of silvery-white spots; it has a bushy tail, white eye rings, and large ears ( Figs. 1 View Fig and 2 View Fig ). Otospermophilus douglasii has a dark interscapular patch that is most pronounced in adult males, is laterally wider, and extends more caudally than in females. In females, the dark interscapular patch is more pronounced than in immatures. There seems to be a general color gradient, with coastal Oregon populations being darker brown and having extensive silvery fur above the forelimbs, those in central Oregon being medium brown, and those in eastern Oregon being a lighter brown in summer pelage and somewhat grayer in winter ( Edge 1935b; Maser et al. 1981).

Mean measurements (mm; parenthetical ranges) of 17 adult specimens (12 males and 5 females, respectively) from the northwestern California counties of Sonoma north to Humboldt were: total length, 478 (438–504), 439 (427–453); tail vertebrae, 200 (175–221), 192 (161–210); hind foot, 60 (57–63), 57(56–60); ear from crown, 23 (19–29), 23 (18–26— Grinnell and Dixon 1918). Mean measurements (mm ± SE) of female O. douglasii from three regions in Oregon were: coastal Oregon (n = 31), body length 241.05 ± 1.46, tail length 196 ± 0.81, foot length 56.0 ± 0.182, ear length 26.8 ± 0.155; Eugene (central Oregon; n = 30), body length 243.3 ± 1.56, tail length 191.1 ± 1.18, foot length 57.4 ± 0.256, ear length 27.6 ± 0.134; eastern Oregon (n = 33), body length 257.5 ± 1.23, tail length 183.5 ± 1.23, foot length 56.5 ± 0.147, ear length 23.8 ± 0.102 ( Edge 1935b).

Museum specimen data were collected by one of us (DJL) from a series of 83 sexually mature O. douglasii from California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History (LACM), University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ), and University of Kansas Museum of Natural History (KU). These specimens were collected in California ( Humboldt , Lake , Lassen , Plumas , Marin , Mendocino , Napa , Shasta , Siskiyou , Sonoma , Tehama , and Trinity counties) and Oregon ( Klikatat , Lane , Lincoln , and Washington counties). Based on these samples, the average masses were 605.4 g (365– 847 g) for males (n = 38) and 501.0 g (403–661 g) for females (n = 45).

Otospermophilus douglasii shares a skull morphology ( Fig. 3 View Fig ) that is generally indistinguishable from that of O. beecheyi and O. variegatus ( Hall 1926; Oaks et al. 1987; Phuong et al. 2014). Mean cranial dimensions (mm; parenthetical range) of 17 full-grown (12 males and 5 females, respectively) O. douglasii from the northwestern California counties of Sonoma north to Humboldt were: greatest length of skull, 60.5 (57.8– 63.1), 58.5 (56.8–60.4); zygomatic breadth, 37.0 (34.9–38.2), 35.9 (35.0–36.8); interorbital width, 14.3 (13.5–15.7), 14.0 (13.1–15.0— Grinnell and Dixon 1918).

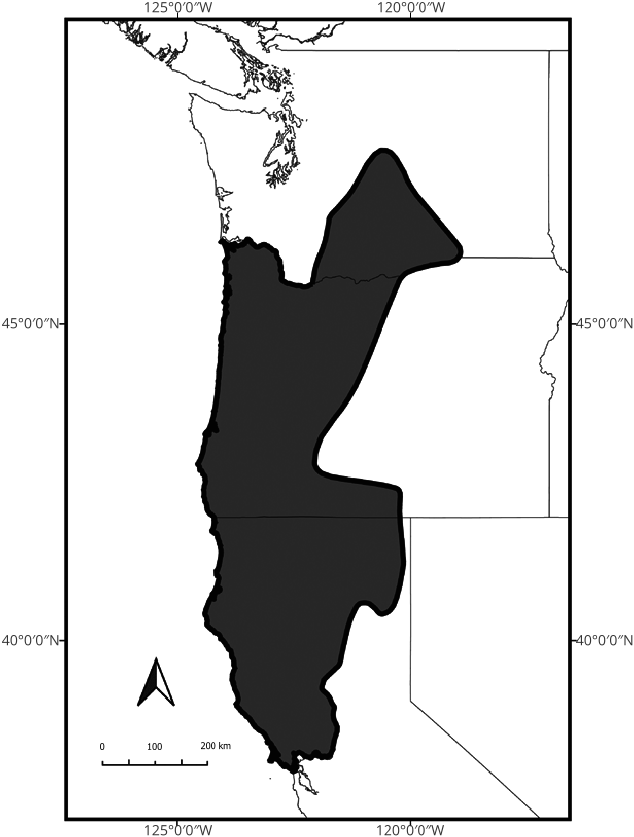

DISTRIBUTION

Otospermophilus douglasii has a distribution that ranges from northern California ( Fig. 4 View Fig ) from the coast and Central Valley at the Sacramento River to the south, extending east to the base of the Sierra Nevada mountain range and northeast into the Modoc Plateau; in Oregon, it has a distribution throughout the Pacific Coast and Cascade ranges and east through the Great Basin west of Nevada, and north into central Washington ( Hall 1981; Verts and Carraway 1998). The original distribution of the species was reported as being from northwestern California north to northern Oregon, excluding Washington State ( Howell 1938). However, O. douglasii was also reported from the Washington shore of the Hood River near the town of Bingen in 1912 before the construction of the nearby Hood River Bridge ( Couch 1922). How the squirrels crossed such a potentially wide dispersal barrier is unclear, though Shaw (1926) describes O. douglasii as being brought from the Rogue River, Oregon, in 1911 and was later released near Pullman in southeastern Washington. Otospermophilus douglasii later spread throughout central Washington ( Scheffer and Dalquest 1939), with the expansion of farmland aiding the dispersal and success of the species. The current northernmost occurrence is from the south end of Cle Elum Lake, about 100 km due east of the city of Tacoma ( Fig. 5B View Fig ). Populations occur at sea level along the coast as well as upslope inland. Grinnell and Dixon (1918) recorded the extent of their elevational range as 1,981 m at South Yolly Bolly Mountain in Tehama County, California, and 2,072 m in the Scott Mountains of Siskiyou County, California. Dalquest (1948) showed a small range of O. douglasii in extreme south-central Washington in Klickitat County between White Salmon to the west and Goldendale to the east.

There is apparently no overlap in the ranges of O. douglasii and O. beecheyi likely because the Sacramento River Basin forms a broad and constant biogeographic barrier between the two species ( Grinnell and Dixon 1918; Grinnell 1933; Howell 1938; Hall 1981; Smith and Coss 1984; Holding et al. 2021). Without providing any specific evidence, Howell (1938) suggested that O. douglasii forms a hybrid zone (rather than an intergrade zone) with O. b. fisheri in Butte County, California. However, Grinnell and Dixon (1918) stated that there was no apparent overlap in ranges between the two taxa in Butte County nor the adjacent Plumas and Lassen counties. Fine-scale population genetics data at the boundaries of the geographic ranges of these species are needed to clearly determine the amount of genetic hybridization, if any, and to delineate the ranges of O. douglasii more clearly from those of O. beecheyi and its subspecies.

FOSSIL RECORD

Fossils of Otospermophilus are known from the middle Miocene through the late Pleistocene in North America ( Kurten and Anderson 1980; Savage and Russell 1983; Goodwin and Martin 2017). Thorington et al. (2012) proposed two possible ancestors for Otospermophilus , either evolving from Miospermophilus in the late Oligocene to middle Miocene (ca. 24–12 Mya) or from Spermophilus in the middle Miocene (ca. 16 Mya). Black (1963) earlier proposed Miospermophilus as the ancestral lineage to Otospermophilus . Fossil and molecular data suggested a date of late Miocene (ca. 5 Mya) for the divergence of Otospermophilus and Spermophilus ( Smith and Coss 1984) . A genetic phylogeny by Harrison et al. (2003) showed that Otospermophilus diverged from other ground squirrel genera in the Miocene (ca. 17.5 Mya) and was not a descendant genus from Spermophilus .

Concerning the specific evolution of O. douglasii, Smith and Coss (1984) suggested a divergence between O. douglasii and O. beecheyi in the middle Pleistocene (ca. 0.725 Mya), which coincides with the development of the Sacramento River and the adjacent marshes and wetlands that produced a permanent barrier between the two populations of Otospermophilus . This eventually contributed to speciation between O. douglasii and O. beecheyi . That is, O. douglasii occurs largely to the west of the Sacramento River Basin; some populations are north of the area of the Sacramento River that connects with the San Joaquin Delta, Carquinez Strait, and the San Francisco Bay. In contrast, O. beecheyi occurs primarily south of the Sacramento River Basin. Phuong et al. (2014) clarified genetic criteria for specieslevel separation of O. douglasii from O. beecheyi . They also analyzed cranial characters of both species and demonstrated that there were no clear morphological traits distinctive of either species, making identification of more recent fossil Otospermophilus difficult. There are also several late Pleistocene records of Otospermophilus from the areas where O. douglasii occur today, including fossil specimens from Hawver Cave, El Dorado County, California, and Potter Creek and Samwel Caves, Shasta County, California ( Kurten and Anderson 1980; Blois et al. 2008).

ONTOGENY AND REPRODUCTION

Ontogeny.— Much of the information on the seasonal growth of Otospermophilus douglasii was established through the combined field and lab observations by Edge (1931). Specifically, he noted the growth trajectories for five offspring born in the lab after their wild-caught mother was live-trapped and observed in the lab. Her newborn offspring weighed, on average, 11.8 g. They were hairless with red, wrinkled skin, closed eyes, and showed little motor control ( Edge 1931). By the second week of life, these young averaged 24 g, their skin color darkened, and their natal fur began to show on the head and back. By the fourth week, the young averaged 35.2 g, the extent of natal fur had increased, eyes were barely open, and they attempted to move their limbs and raise their head. At 7 weeks, the young averaged 64.5 g and began to show pigmented hair throughout the body, their eyes were fully open, and they could move about with control and dexterity. By the eighth week, the young averaged 73 g and began foraging on solid food. These lab measurements suggest that young in the field venture out of the burrows at about 7–8 weeks of age ( Edge 1931).

In the field, juveniles were noted to venture out of their burrows in June in central Oregon ( Edge 1931), and June and July in several northern California counties ( Grinnell and Dixon 1918), with weaned offspring leaving the dens earlier in lower elevation habitats, and later in higher elevation habitats. Adults begin accumulating body fat at the end of summer and maximize fat stores by the end of September, preceding the start of inactivity in November ( Maser et al. 1981). Although there is little activity during winter, both adults and juveniles emerge during warm or dry spells during winter ( Edge 1931). Edge (1931) trapped adult females earlier in the spring than he trapped adult males. However, additional study is required to understand whether robust sex differences in activity exist in O. douglasii . In contrast, for most ground squirrels, including O. beecheyi , adult males are active above ground earlier in the spring than adult females in areas with seasonal activity patterns ( Smith et al. 2016). One removal study suggested that the young of the year typically dispersed from the natal social group by the end of the summer; a small number of adults also dispersed from populations of higher densities to populations of lower densities ( Stroud 1982). Discounting predation and disease, Edge (1934) estimated the maximum life span to be 5–6 years. Whether the sexes differ in their longevity is currently unknown.

Reproduction.— Reproductive information on Otospermophilus douglasii is sparse, but Maser et al. (1981) noted that enlargement of testes in adult males begins in February, and males are in breeding condition by March. Mating season for O. douglasii in western Oregon occurs from late February through early March ( Bickford 1980) but the timing of reproduction varies regionally ( Chapman and Lind 1973). Most females are pregnant by the end of March; birth and lactation occur from May to June ( Bickford 1980). Weaning occurs by mid-July ( Bickford 1980). In central western Oregon, the start of mating was observed in late March and mating peaked in early April; females were in the early stages of pregnancy at the start of April ( Edge 1931). Births and lactation occurred in the last week of April through May, suggesting an overall gestation period lasting 25–30 days. Females collected in northern California were carrying 5–6 embryos between late April and middle May, with some near parturition in late May ( Howell 1938). In Yolo County, California, the southern end of the geographic range of O. douglasii , breeding in mid-March, and recently emerged litters at the beginning of July were noted ( Owings et al. 1979). Litter sizes may be related to female size ( Edge 1931). He found larger females were more fecund (seven embryos) than smaller females (three embryos); however, prenatal mortality occurred in some females, suggesting that the initial number of embryos may not produce the same litter size at birth ( Edge 1931). Females likely produce only a single litter per year ( Grinnell and Dixon 1918).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Otospermophilus douglasii ( Richardson, 1829 )

| Long, Douglas J. & Smith, Jennifer E. 2023 |

Otospermophilus douglasii

| Edge E. R. 1931: 194 |

Otospermophilus grammurus douglasii

| Miller G. S., Jr. 1924: 181 |

Citellus douglasii

| Couch L. K. 1922: 18 |

| Grinnell J. & Dixon J. S. 1918: 644 |

Citellus beecheyi douglasi

| Grinnell J. 1913: 345 |

Citellus

| Elliot D. G. 1903: 183 |

Spermophilus (Otospermophilus) grammurus douglasi

| Elliot D. G. 1901: 89 |

Spermophilus grammurus douglassi

| Bryant W. E. 1891: 355 |

Spermophilus grammurus

| Allen J. A. 1874: 293 |

Spermophilus douglasii

| Cuvier M. F. 1831: 333 |