Halistemma foliacea

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3897.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CB622998-E483-4046-A40E-DBE22B001DFD |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FC87BC-FFE5-FFB6-FF62-AB2F6386FA6F |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Halistemma foliacea |

| status |

|

Halistemma foliacea View in CoL ( Quoy & Gaimard, 1833 ( 1834))

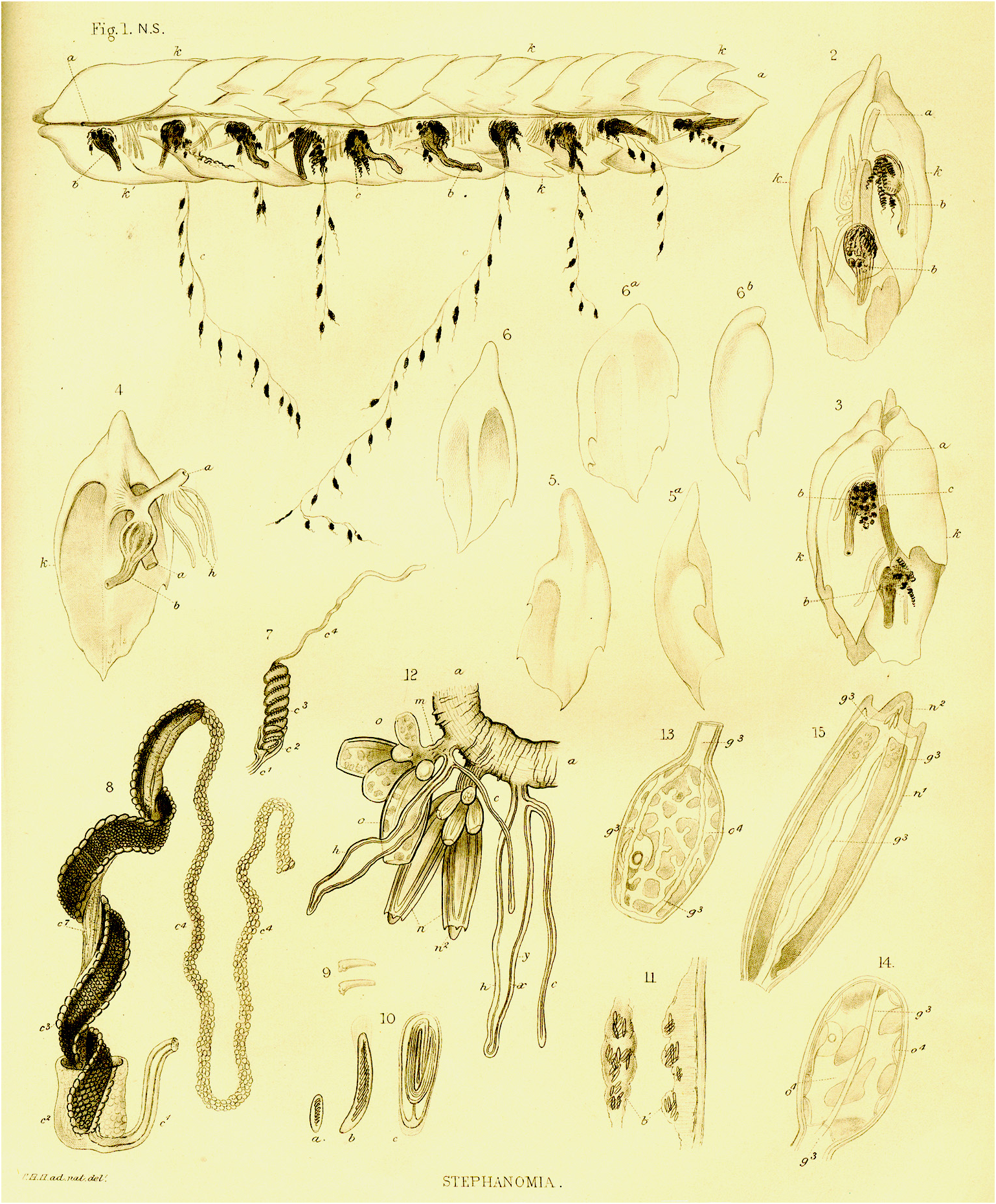

Stephanomia foliacea Quoy & Gaimard, 1833 ( 1834) , p. 74, Pl. 3, figs. 8–12; Blainville, 1834, p. 119; Lamarck, 1840, p. 28; Huxley, 1859, p. 136; Haeckel, 1888b, p. 225; Bedot, 1896, p. 384; Bigelow, 1911 b, p. 355;

Stephanomia amphitridis Huxley, 1854, p. 72 , Pl. 6; Bigelow, 1911 b, p. 287, Pl. 18, figs. 1–8;. Kawamura, 1954, p. 110.

Phyllophysa foliacea L. Agassiz, 1862, p. 368 ; Haeckel, 1888a, p. 40; 1888b, p. 225; Bedot, 1896, p. 399.

Phyllophysa squamacea Haeckel, 1888b, p. 225 .

Halistemma amphytridis Mapstone, 2004, p. 232 , figs. 1–3.

Halistemma foliacea Pugh, 2006, p. 42 View in CoL .

? Stephanomia nereidum Haeckel, 1888b, p. 221 .

Diagnosis. Nectophores with two, complete pairs of vertical lateral ridges. The lateral ridges do not connect with the upper lateral ones. Four types of bract, all, to a varying degree, with a distinct median keel on the lower side. The "ventral" bracts have a very characteristic semicircular indentation on their inner side of the distal half. Terminal filament of mature tentilla with small cupulate process.

Material examined. Specimen collected at Snellius I Station 317a at 7°55.0'S, 122°12.5'E, to the north of Flores, Indonesia, on the 22 nd August 1930. The specimen probably was collected in a 50 cm diameter opening plankton net, 1 m GoogleMaps in length towed at the surface. The water depth was 2350 m.

Description.

Pneumatophore. The small pneumatophore was greatly distorted and bore an apical cap of dark red pigmentation

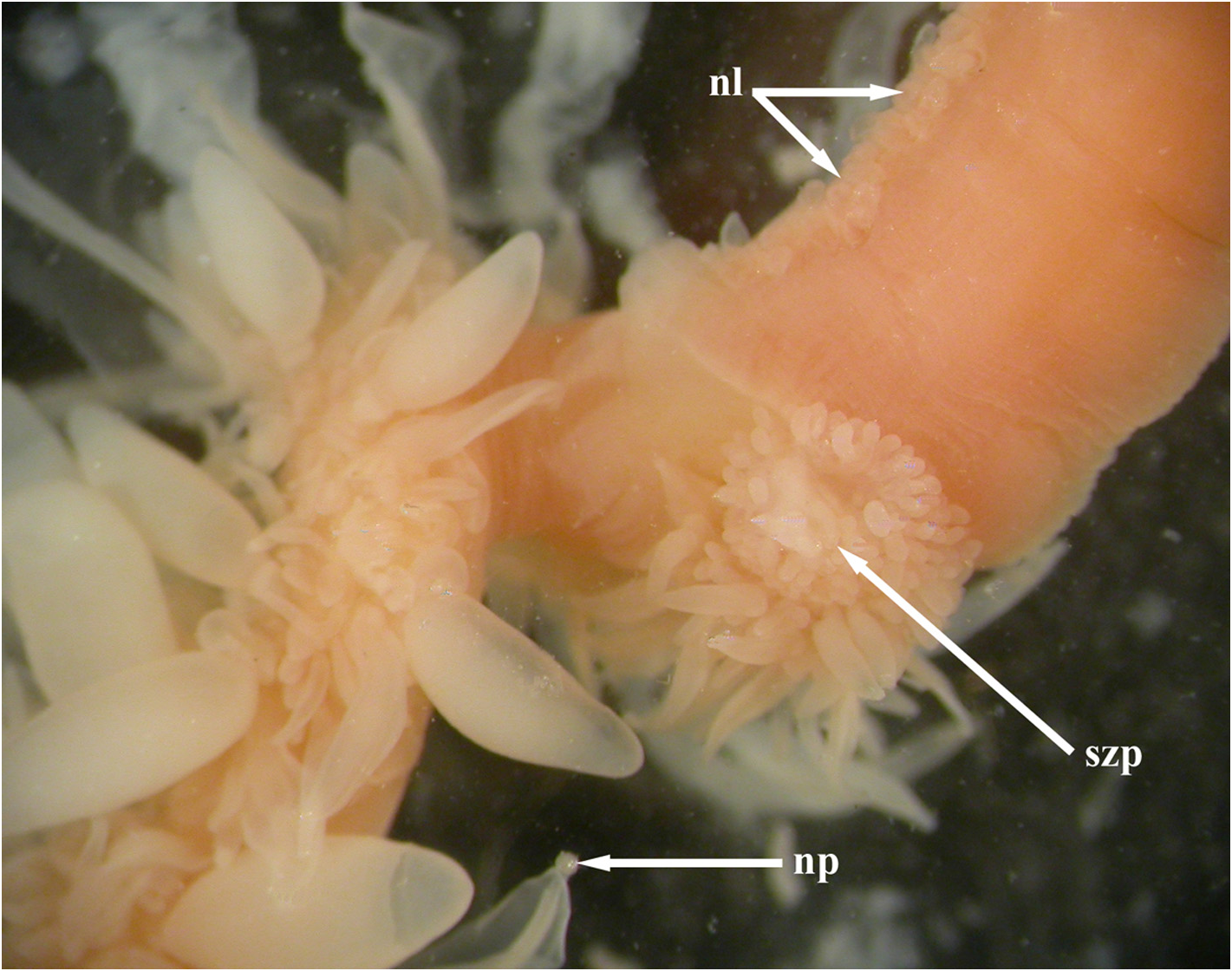

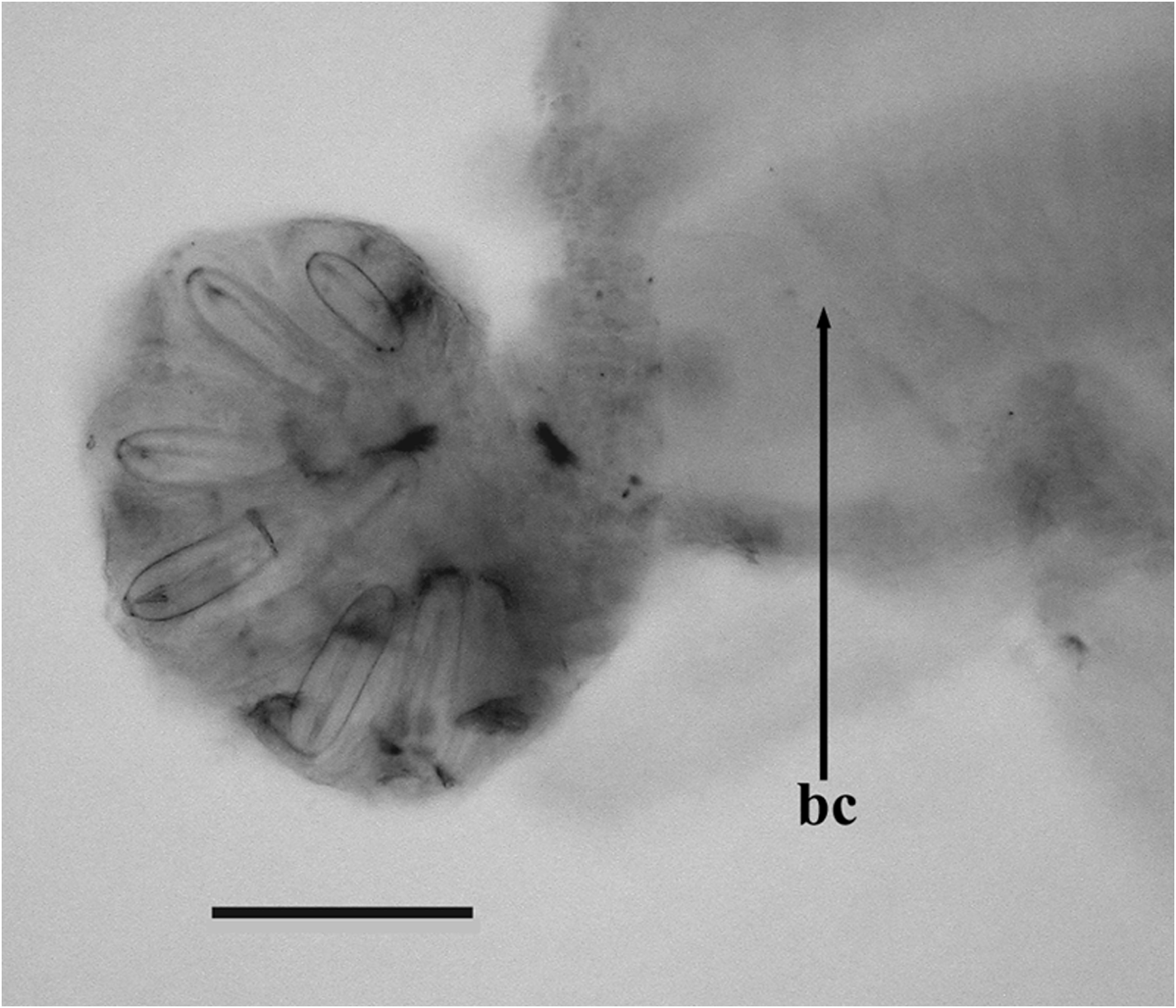

Nectosome. Typically the nectophores were budded off on the dorsal side of the nectosome ( Figure 60 View FIGURE 60 ), despite Mapstone's (2004) statement to the contrary. The nectosome and siphosome were a brownish orange colour in their preserved state.

Nectophores: The Snellius specimen included 45 mature nectophores and a very young one. The mature nectophores were, generally, in a poorish condition, as one might expect from net collected material. No patches of ectodermal cells were noted on the lateral surfaces of any of the nectophore, but one cannot be certain that they are truly absent. The very young nectophore ( Figure 61 View FIGURE 61 ) clearly showed the characteristic feature of the nectophores of Halistemma foliacea , that was the two pairs of vertical lateral ridges. The upper lateral ridges reached to the ostium and, at this stage, had a slight kink proximal to the ostium. The lateral ostial processes were relatively large but there were no obvious large nematocysts.

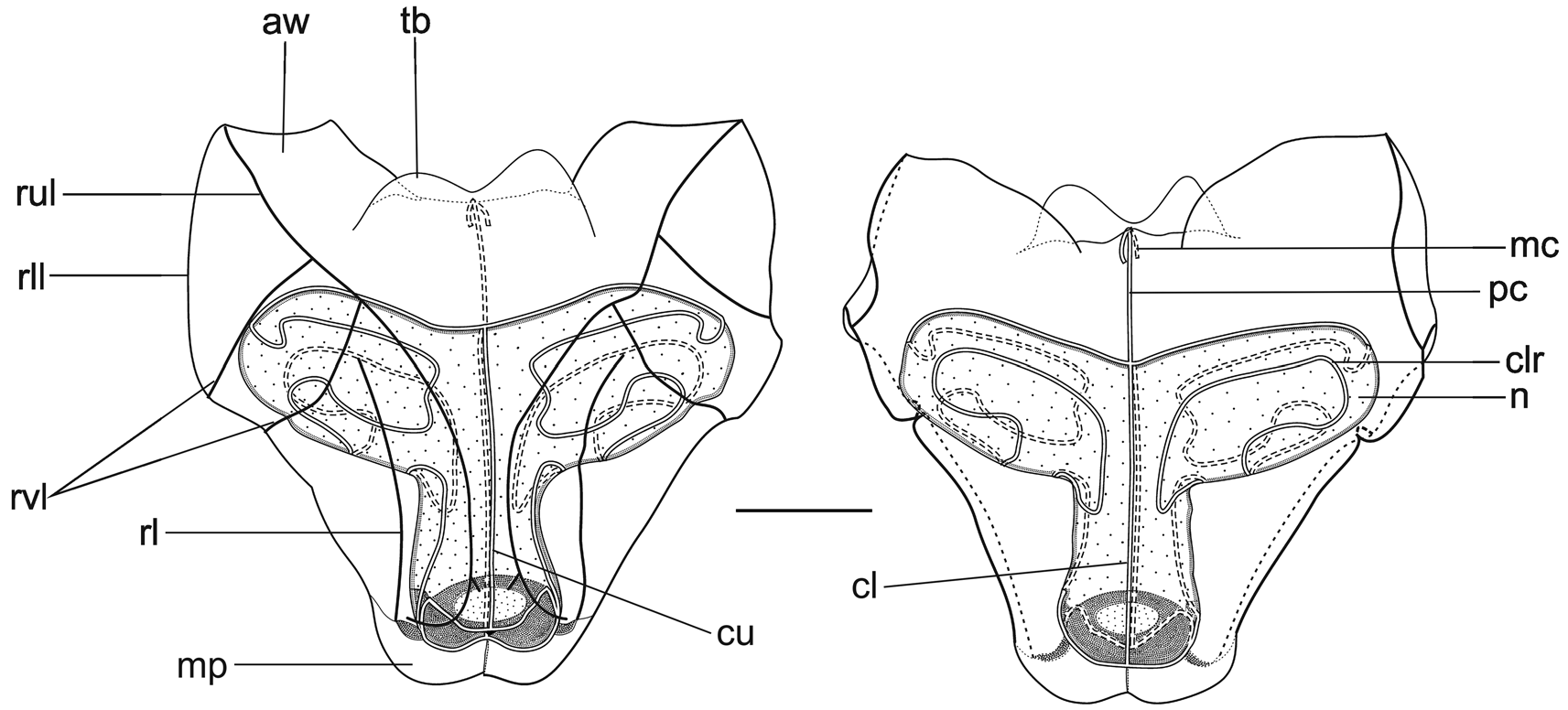

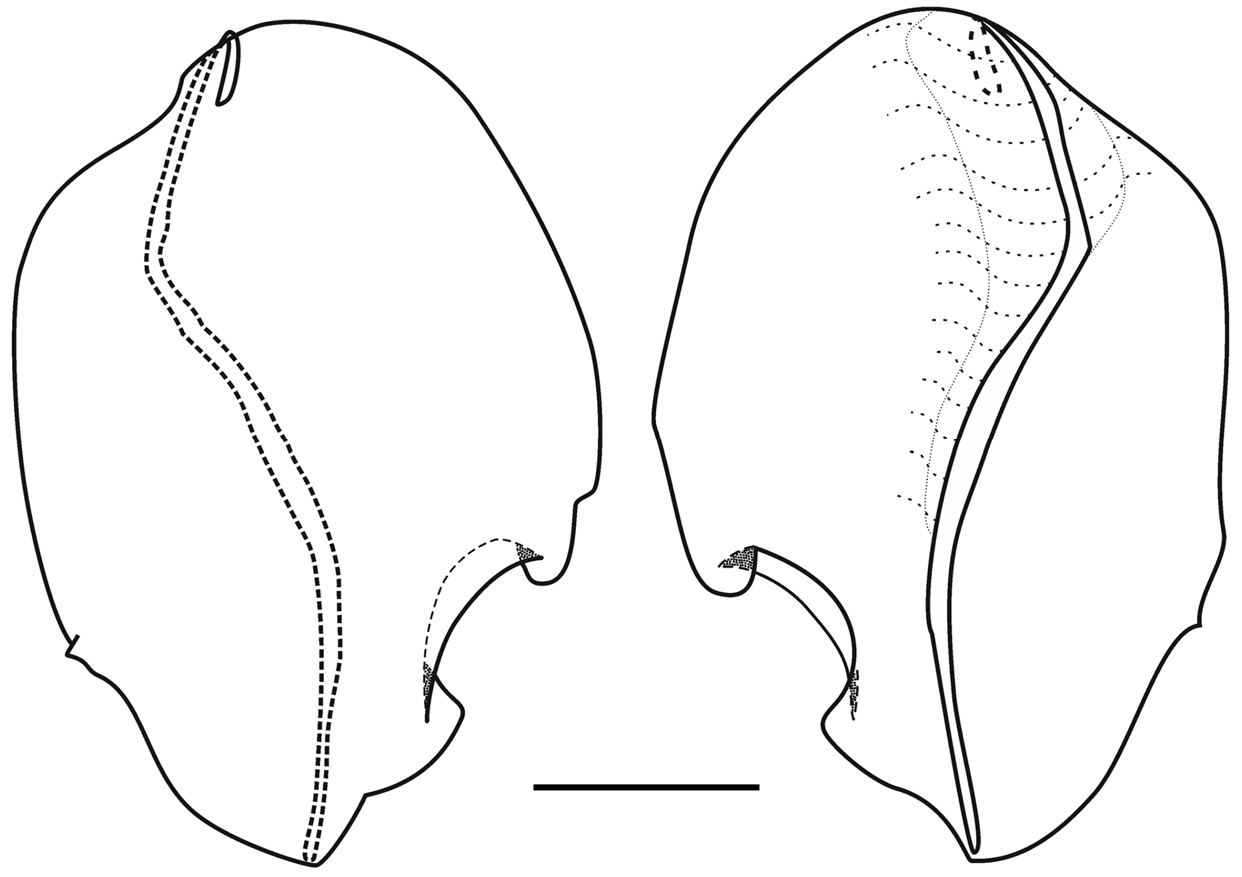

The adult nectophores ( Figure 62 View FIGURE 62 ) were very flimsy, often damaged, and many had the lining of the nectosac completely detached. The upper and lower lateral ridges met at the outer proximal tips of the axial wings. The upper laterals ran obliquely inwards toward the ostium, but the degree to which they approached each other was quite variable. Shortly above the ostium they began to diverge and each gave rise to a short inner branch, while the outer branch continued out laterally and eventually petered out in the region of the lateral ostial processes. The lower lateral ridges continued down the lower sides of the nectophore and eventually merged with the mouth plate. The rounded, relatively small mouth plate had a central, broad emargination, and the "ventral nerve tract" (see Mackie 1973) could clearly be seen running in the mid-line to join the ostium. The two pairs of vertical lateral ridges were distinct and complete. There was a furrow paralleling the more distal pair of ridges, but such furrows, particularly on the upper surface, are usually preservation artefacts. The pair of lateral ridges ran proximally and obliquely up from the ends of the lateral ostial processes, but did not connect with any other ridge.

The central thrust block was broad, but not greatly developed. It had a broad central emargination. The axial wings were proximally truncated, particularly in upper view. They too were not greatly developed and varied in the extent to which they projected from the main body of the nectophore. Most often they projected beyond the top of the thrust block, but not uncommonly they were virtually non-existent, with the thrust block extending beyond their proximal ends

The nectosac was roughly T-shaped, with a relatively narrow neck; although this probably was a preservation artefact due to the poor state of the nectophores. The ascending and descending branches of the mantle canal were quite short and of approximately the same length. The long pedicular canal ran down from the lower side of the thrust block to the top of the nectosac, where it gave rise to all four radial canals. The upper and lower canals ran straight down to the ostial ring canal. The course of the lateral radial canals was the most complex of all the Halistemma species and is better illustrated ( Figure 62 View FIGURE 62 ) than described in detail. There was a small patch of ectodermal cells on the velum close to where the upper canal joined the ring canal. The two lateral ostial processes were relatively small, and were covered by distinctive cells. These processes had usually become detached, except by the ostium, so that they appeared as flaps.

Siphosome. Bigelow (1911, p. 288) gave a description of the arrangement of the zooids in each cormidium of his specimens of Stephanomia amphitridis [sic], noting that "The cormidia have been described by Huxley, but the location of the various zooids is more precise than he supposed. In the present series there are nineteen siphons, with corresponding segments of stem, and in all of them the arrangement is as follows:—Proximal to any given siphon there are from 2–5 palpons; distal and close to it are the two gonodendra, ♀ and ♂, and crowded against them 3–6 palpons. On the pairs the of ♂ cluster is always next the siphon … Next to the ♀ gonodendron there is a vacant space occupied only by bracts; but midway between every two siphons there is a cluster of 3–6 palpons of different ages". This basic arrangement has been confirmed for the present specimen as is discussed below .

Bracts. Huxley (1859) thought for his specimen of " Stephanomia amphitridis " that there were two types of bracts arranged in four whorls, with pairs of laterals differing from the identical dorsal and ventrals (see Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Bigelow (1911, pp. 287–8), however, considered the bracts to be arranged into "four or five irregular somewhat diagonal rows", and "that their external location does not necessarily indicate the level at which their supporting lamellae join the stem". Nevertheless, he noted three types of bract that he designated "dorsal", "lateral" and "ventral"; a convention followed by Mapstone (2004). For the Snellius specimen she counted 161 "dorsal", 44 "lateral", and 12 "ventral" bracts. However, if the bracts had been arranged into four or more rows then one might expect the number of lateral bracts to be at least twice that of the other types. Thus, judging by the relative numbers found with the Snellius specimen, one wonders if Bigelow's designations were entirely correct, but unfortunately he gave no numbers for each type. Nevertheless we will follow his designations here, although we consider that there are two types of lateral bracts.

"Dorsal" bracts: Most of these bracts were in poor condition. They measured up to 32 mm in length by 19 mm in maximum width. At all stages of development the bracts distal end came to a median point, and up to two, slightly asymmetrical pairs of lateral teeth were present; although they were always very small and indistinct, often appearing just as small notches.

The younger "dorsal" bracts ( Figure 63 View FIGURE 63 ) were flattened in the upper/lower plane, but with a small median enlarged region, like a keel at the proximal end on the lower surface. The broad bracteal canal was widest in its central region and narrowed in both the proximal and distal directions. At the proximal end it curved over the thickened keel and up toward the upper side of the bract. At the distal end it might have been inflected slightly into the mesogloea, but the latter was very thin in that region. Although Mapstone (2004, p. 236) stated that the distal end of the bracteal canal was "terminating as small swollen apical button in cup-shaped depression filled with nematocysts" this was not found to be the case by the present authors. A single young "dorsal" bract, out of all the detached bracts of the three different types, showed that the bracteal canal ended, distally, below a ball of tissue that protruded out from the tip of the bract, in which nematocysts, probably stenoteles, were embedded, ( Figure 64 View FIGURE 64 ). A close study of the anterior end of the siphosomal stem shows that there are still some young "dorsal" bracts attached and showing this sphere of nematocysts at their distal tip (see Figure 60 View FIGURE 60 , np). However, more posteriorly, for the more developed "dorsal" bracts, this sphere of nematocysts has become detached, leaving a small, empty cup-shaped depression. No young bracts of the other types were seen on the siphosomal stem and so it is unclear whether they also develop such a sphere of nematocysts, but there was no evidence for it on the detached bracts.

As the bracts grew the proximal keel on the lower side of the bract became more prominent and gradually the bracteal canal narrowed ( Figure 65 View FIGURE 65 ). Firstly, the keel became displaced toward the inner side of the bract, and no longer reached to the proximal tip, which had begun to elongate so that the bracteal canal usually remained on the lower side of the bract. At some stage, but not necessarily concomitant with the proximal elongation, the proximal region of the bract began to become thickened with mesogloea. Thus in some cases ( Figure 65 A View FIGURE 65 , left) the bracteal canal continued to the proximal end and up toward the upper surface, and on its outer side (right in figure) the proximal end of the bract became thickened, while the other side was distinctly thinner, so that the narrow keel, in the preserved state at least, often formed a flap partially covering it. In another ( Figure 65 A View FIGURE 65 , right) the proximal end of the bract had begun to elongate and its central part was thickened, still with the distinctive keel running over it. In the fully developed bract ( Figure 65 B View FIGURE 65 ) the entire proximal end of the bract became thickened with mesogloea and formed a cone shaped structure, while the whole bract resembled a rhomb. However, in the mid region of the bract, on the inner side, the extent and appearance of the mesogloeal thickening could be very variable. The distal end always remained thin and, as above, it was difficult to decide whether the bracteal canal actually penetrated into the mesogloea before terminating.

Although not noticeable in the youngest bracts, as the bracts mature the proximal tip of the bracteal canal tended to enlarge slightly. Sometimes this was an internal swelling without affecting the width of the canal, sometimes it was expanded laterally and often it was slightly inflected into the mesogloea.

"Lateral" bracts: Although Mapstone (2004, p. 238) noted that there were two types of lateral bract she illustrated only of them in her Figure 3, and based the differentiation of the two types mainly on the distribution of the lateral teeth. However, there appear to be more substantial differences between them. Both types measured up to c 30 mm in length, but the second type tended to be wider than the first. At all stages of development both types were distinctly asymmetrical and occurred in enantiomorphic forms.

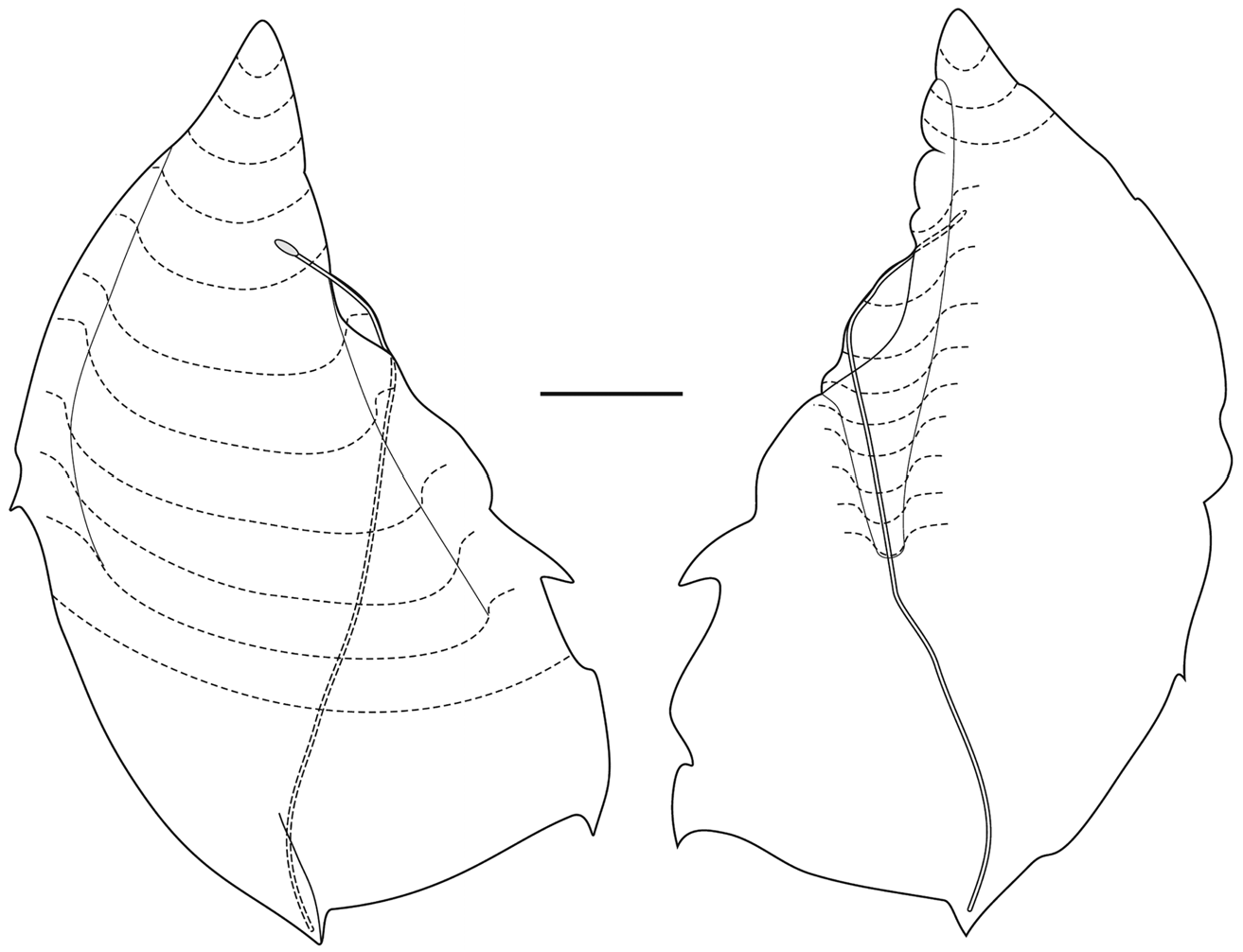

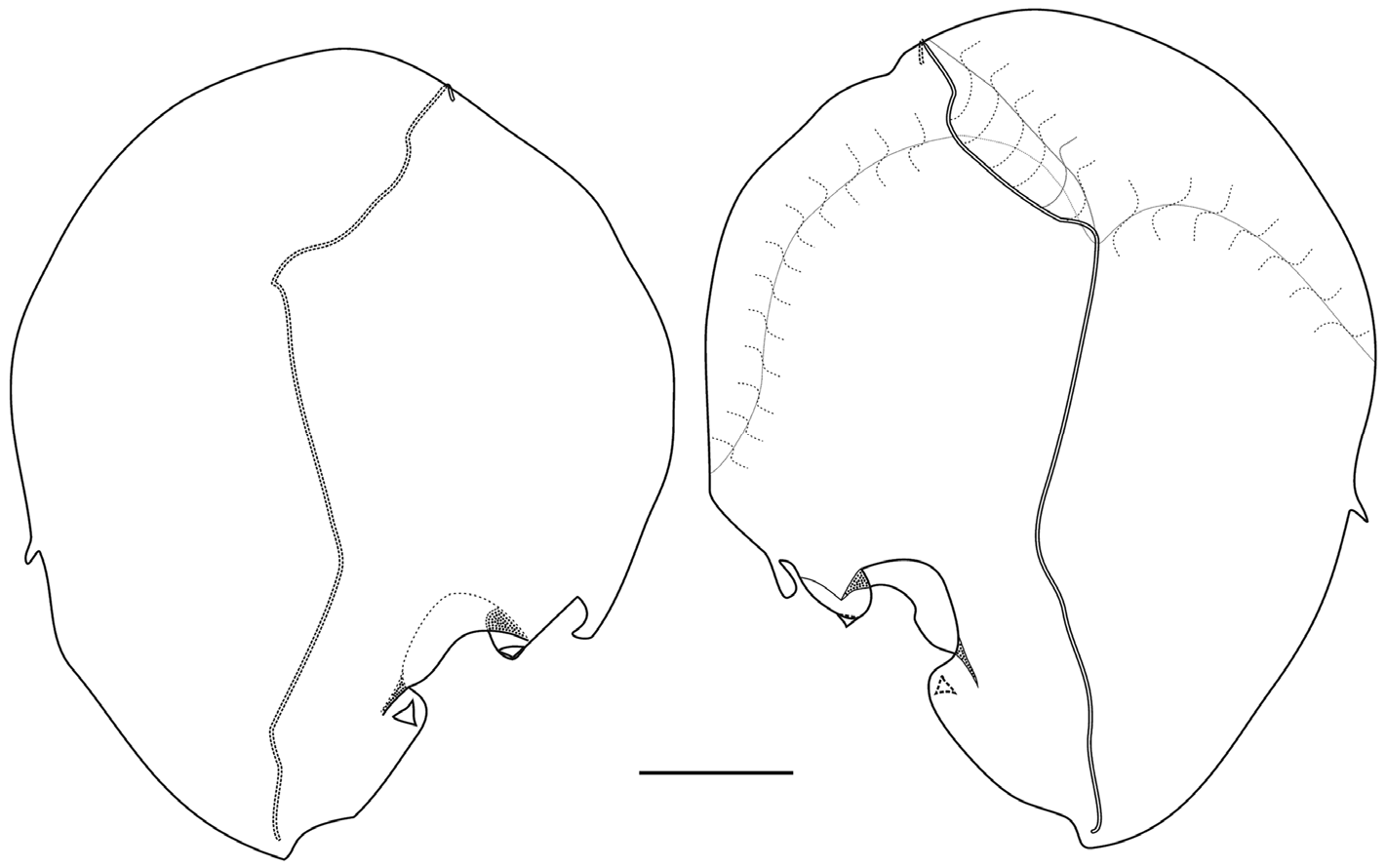

The Type I bracts ( Figures 66 View FIGURE 66 left, 67), which were about twice as common as the other type, were distinctly convex on their upper sides, particularly in the central part of the proximal half. For the younger bracts ( Figure 66 View FIGURE 66 , left), the distal end was pointed, while the proximal end was formed by a rounded cone like process. Toward the distal end there was a pair of lateral teeth; slightly asymmetrical in position and size. On the inner side there was an additional lateral process at about the mid-height of the bract. The proximal end of the bracteal canal often was slightly enlarged and inflected into the mesogloea. It then ran along the upper side before running over the inner lateral side, on to the lower side, and ran distally, initially over the edge of a slightly thickened keel, which at one point overhung the lower side, forming a small cavity. It was greatly thickened in its mid region tapering down both proximally and, particularly, distally. The canal ended at the distal tip of the bract, where there was no sign of an accumulation of nematocysts.

For the mature Type I bracts ( Figure 67 View FIGURE 67 ) the convexity of the upper surface was very obvious in its proximal two-thirds, as indicated by the dotted lines in Figure 67 View FIGURE 67 (left).. The pair of lateral teeth was distinctly asymmetrical in their positioning, with the one on the inner side being larger than the other. The lateral process, on the inner side, was prominent and now resembled an enlarged tooth or cusp. The bracteal canal, now narrow and of equal diameter, lay almost exclusively on the lower side of the bract. Proximally, however, it originated on the upper side of the bract and usually began with a small swelling that could be inflected into the mesogloea. As with the younger bract, the proximal part of the canal ran over the edge of the now thickened keel, which extended more laterally than the upper side of the bract and to above the mid-height of the bract ( Figure 67 View FIGURE 67 , right). There was an indication of a short median ridge descending from the distal end of the bract on the upper side ( Figure 67 View FIGURE 67 , left).

The Type II "lateral" bracts ( Figures 66 View FIGURE 66 (right), 68) differed markedly from the Type I ones in having a large excavated area on the upper and inner side of the bract, where the mesogloea between the upper and lower sides was quite thin. Both the distal and proximal ends of the bract were pointed, although the proximal end often was bent to one side. The excavated region was demarcated by a median, slightly elevated ridge running distally from the rounded proximal process to about the mid-height of the bract. It overhung the excavated upper side for most of its length. The distal border of the excavated area was formed by a thickened cushion of mesogloea whose distal side was demarcated by a shallow gutter. On the side of the cushion closest to the mid-line there was a distinct, but small, flap or rounded cusp ( Figure 68 View FIGURE 68 left, arrowed). Proximally, the bracteal canal lay entirely on the upper side of the bract and ended in a slight swelling, often inflected into the mesogloea, that lay beneath the overhanging median ridge. About halfway across the excavated region it passed over onto the lower side of the bract and ran distally over a marked, but fairly shallow, keel that extended to about half the length of the bract. It then continued toward the distal end but terminated before reaching it, and again without any sign of a patch of nematocysts being present. The proximal part of the bract, on its lower side was more thickened with mesogloea than the distal part and, particularly for the younger bracts, the distal tip was very thin. In addition the younger bracts tended to have only one small lateral tooth, distally, while the mature ones has a pair, arranged asymmetrically.

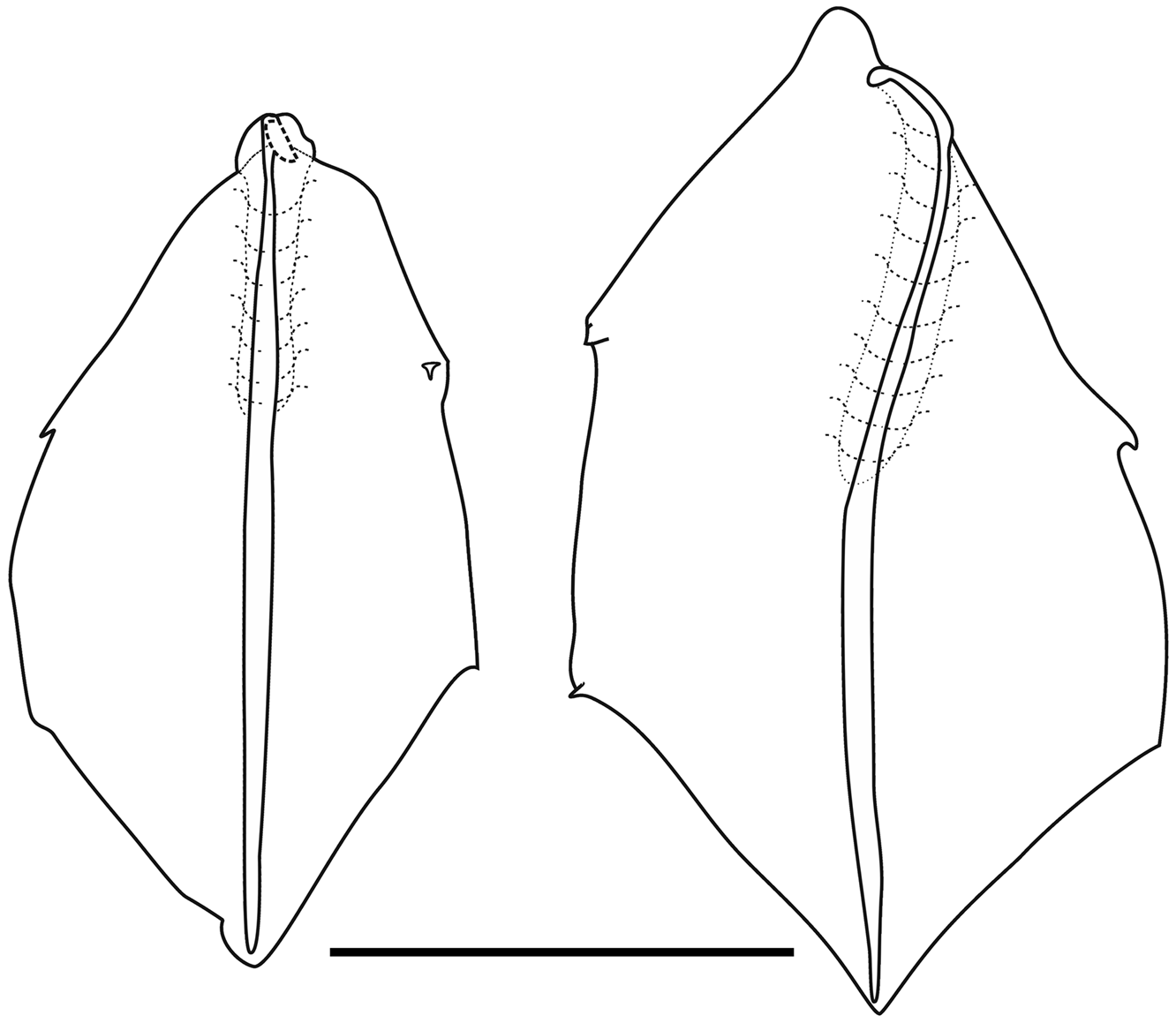

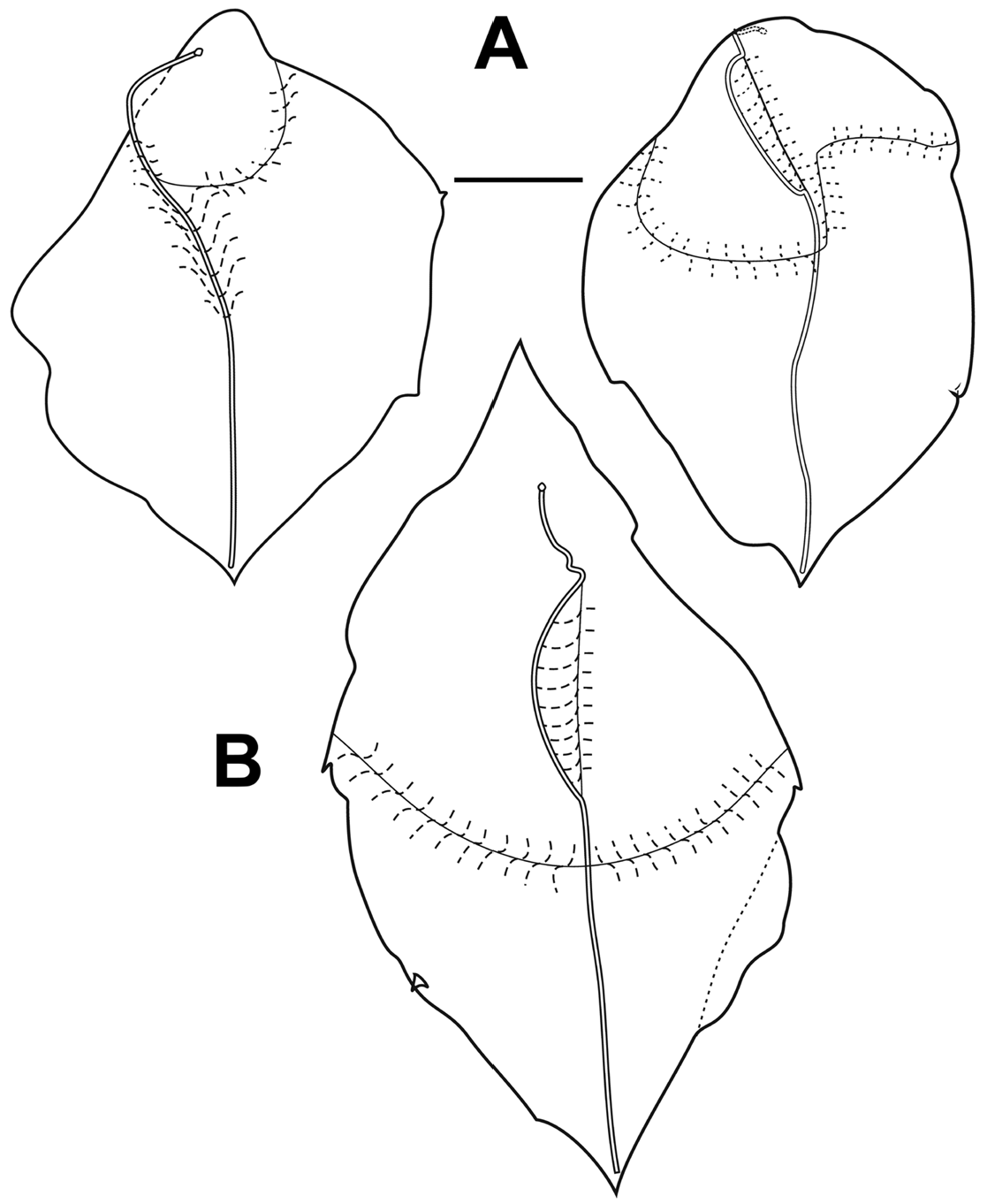

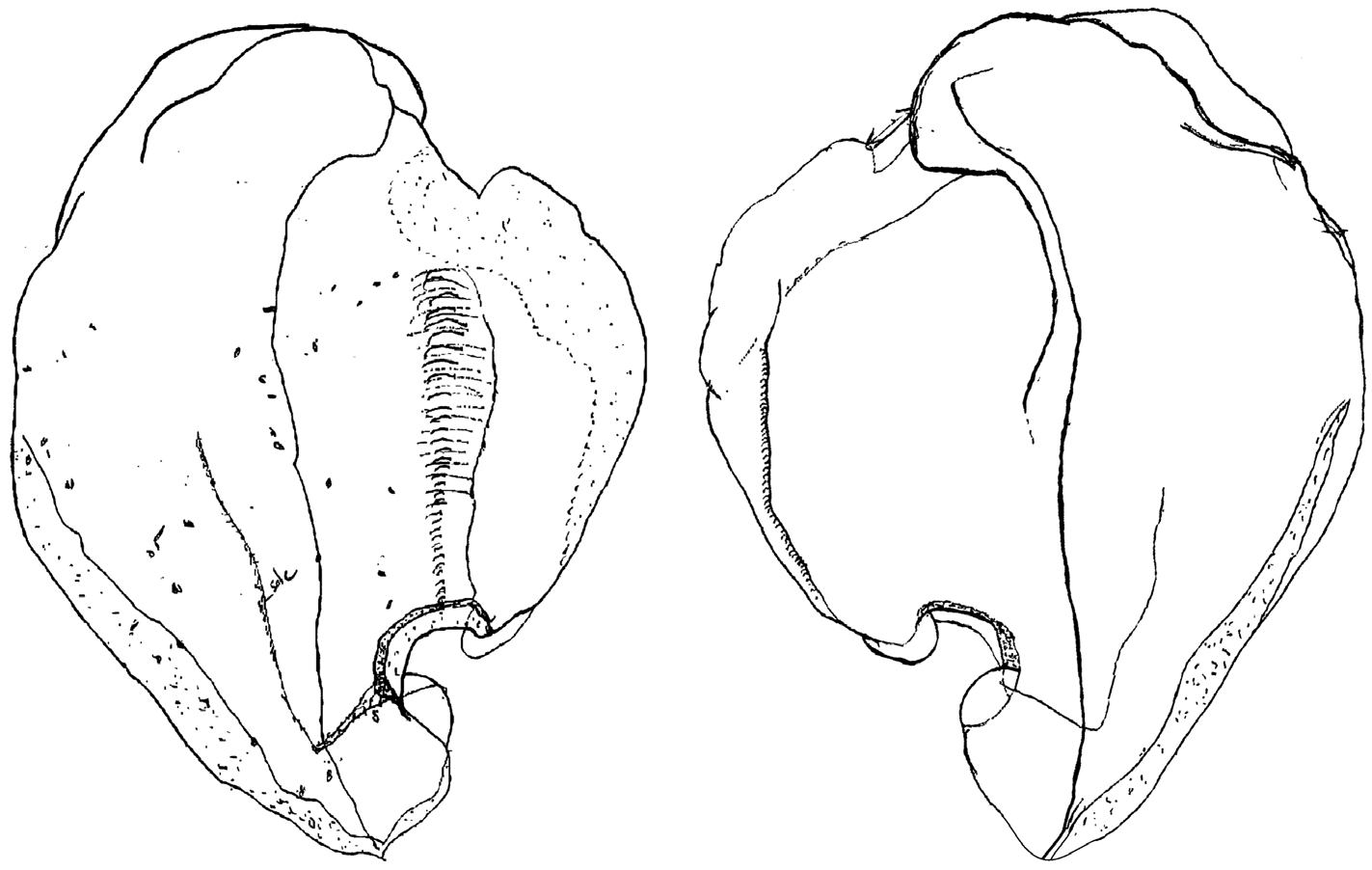

"Ventral" bracts: These were the most distinctive of all the bract types and the least common. They measured up to 27 mm in length and 22 mm in maximum width. At all developmental stages they had an obtuse distal tip, while the proximal end was rounded. On their outer sides the bracts were distinctly emarginated to form a hemispherical indentation, partially overlain by a flap on the upper surface. Although not visible on the younger bracts ( Figure 69 View FIGURE 69 ), the older ones ( Figure 70 View FIGURE 70 ) usually possessed a small tooth immediately above and below the indentation, on the upper surface of the bract. There was also a relatively large process on the outer surface of the mature bracts, just proximal to the indentation, which was represented by only a small notch in the younger ones. At all developmental stages there was another small tooth on the opposite, inner side of the bract at approximately the same level as the indentation.

The younger bracts ( Figure 69 View FIGURE 69 ) possessed a shallow but broad keel in the proximal half on the lower surface. On the mature bracts this keel was relatively short and narrow, but much more pronounced, such that in the preserved specimens it often bent over the inner side of the bract forming a sort of flap. Also on the lower surface the proximal end of the bract was distinctly thickened with mesogloea. This thickening was more pronounced on the outer side. The proximal end of the canal lay on the upper side of the bract; a feature more obvious in the younger ones. There was no obvious swelling or inflexion into the mesogloea. It then passed onto the lower side and ran distally over the middle of the keel and, with a zig and a zag extended to close to the distal end of the bract. In the younger bracts the canal was thickened, particularly in its central region, and tapered down toward the distal end. Very close to its distal end the canal penetrated through the thin layer of mesogloea to end on the upper surface; occasionally below a small cavity, but there was no indication of the presence of nematocysts.

Gastrozooid and tentacle. The gastrozooid ( Figure 71) was fairly cylindrical with a large basigaster occupying one quarter to one third its length. The stomach and proboscis regions were not well distinguished and narrow hepatic stripes could be seen ascending from the mid-height of the gastrozooid to the distal mouth. The tentacle was annulated, with each tentillum arising in the restriction between each segment.

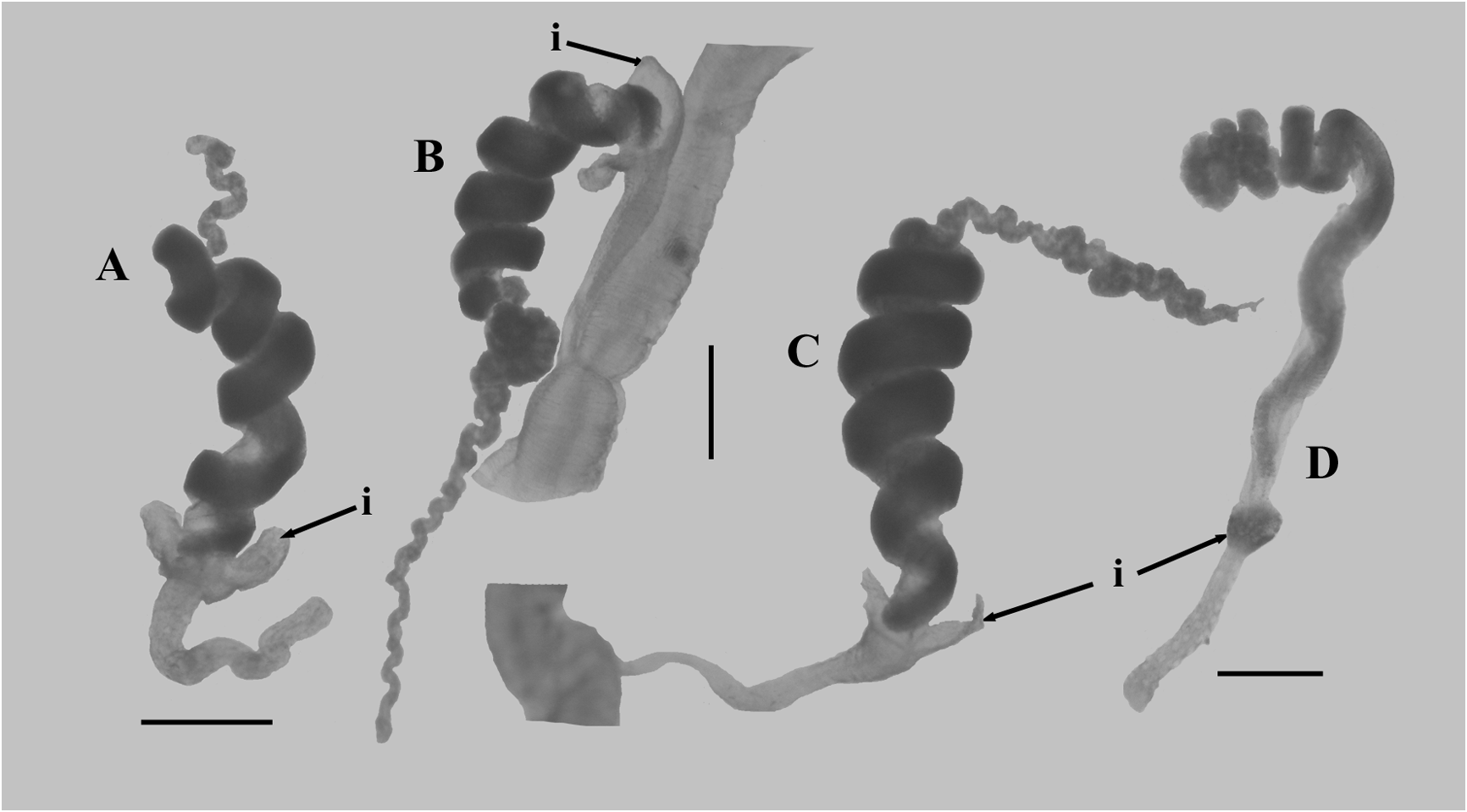

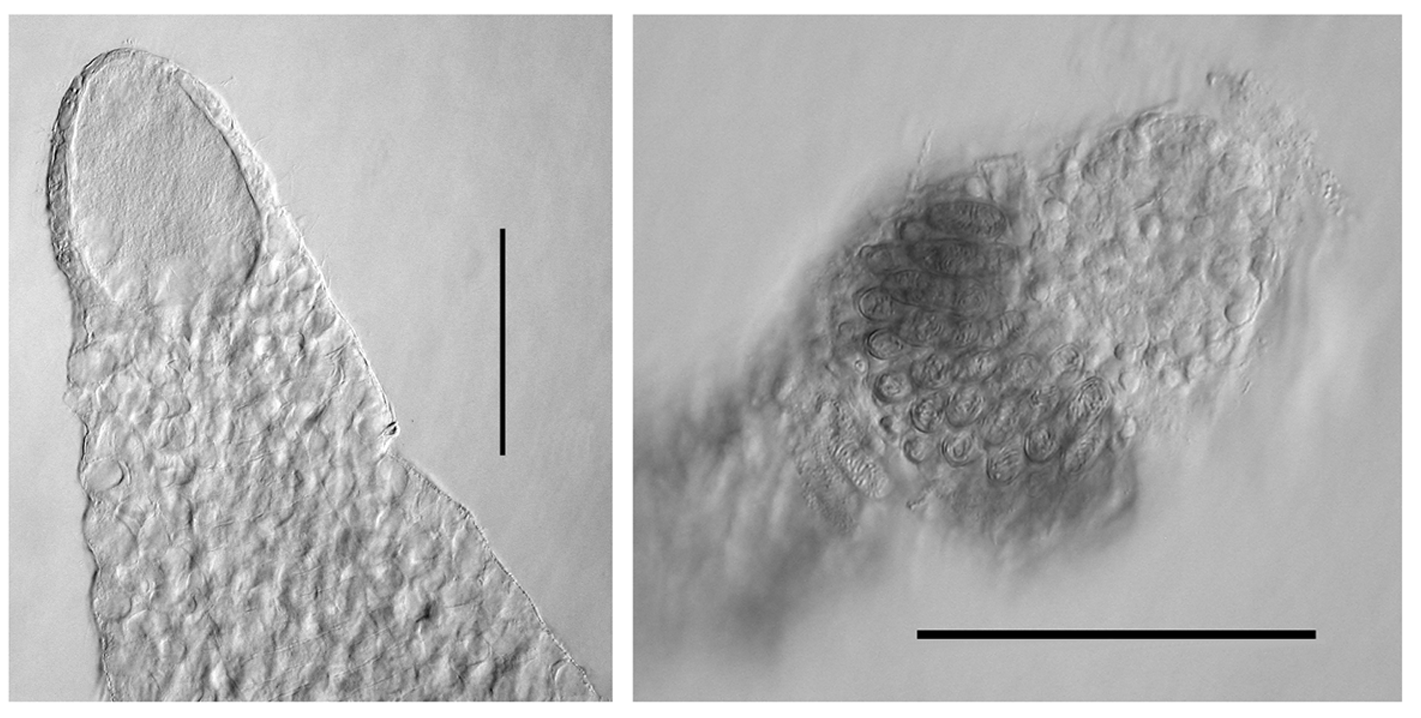

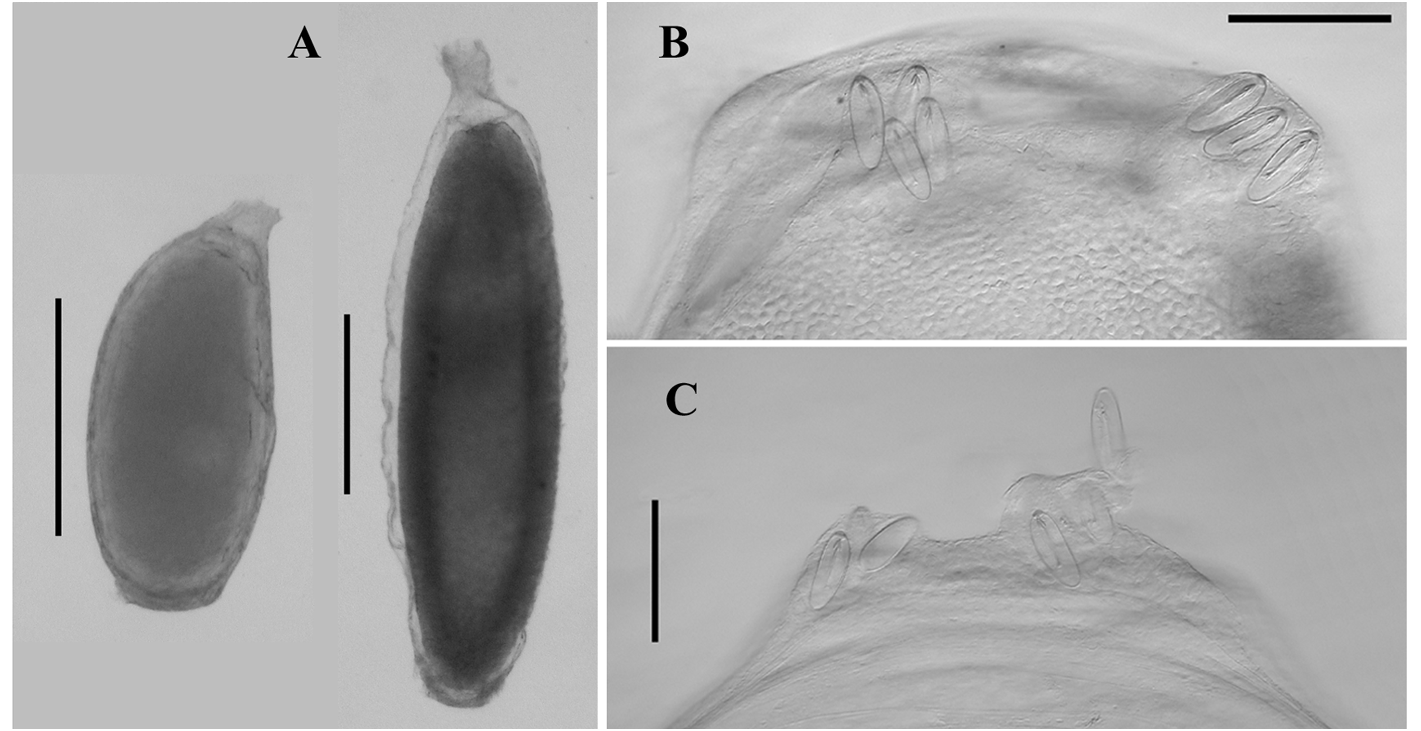

Tentilla. The tentilla possessed an involucrum at the proximal end of the cnidoband ( Figure 72 View FIGURE 72 ) that consisted of two lobes, either symmetrical ( Figure 72 A View FIGURE 72 ) or asymmetrical ( Figure 72 B, C View FIGURE 72 ). During development these lobes were thickened and quite prominent, but as the tentilla matured they expanded into thin sheets, surrounding the proximal end of the cnidoband, that were extremely flimsy and easily torn, such that only a vestige of them may remain ( Figure 72 View FIGURE 72 , D). At earlier stages of development the cnidoband was usually quite tightly coiled into c. 5 spirals, but as it matured the proximal coils straightened, although the spiralling could still be discerned. The double elastic band ran through the interior of the cnidoband. The long terminal filament ended in a small cupulate process ( Figure 73 View FIGURE 73 , right). In the youngest tentilla ( Figure 73 View FIGURE 73 , left) this process was formed by an acorn-shaped process, devoid of nematocysts. However, when mature the base of the acorn-shaped process, itself still devoid of nematocysts, was surrounded by a cupulate swelling that included nematocysts, mainly desmonemes.

Two types of nematocyst were present on the cnidoband; stenoteles and anisorhizas. There were over 200 stenoteles arranged in two rows on either side of the proximal part of the cnidoband. They measured c. 70 µm in length and 25 µm in diameter. The myriad of anisorhizas were banana-shaped, broader at the cap end and roundly pointed at the other, and measured c. 47 µm in length and 9 µm in diameter. The terminal filament had the usual desmonemes and acrophores. The desmonemes measured c. 22 µm in length and 10 µm in diameter; while the acrophores were slightly smaller, measuring c. 21 µm by 9 µm.

Palpons. The featureless palpons measured up to 17 mm in length ( Figure 74). They were mainly cylindrical, but tapered at each end, with at the distal end a narrow, short proboscis, which occasionally possessed a swollen middle region. The palpacle arose at the base of the palpon and presumably was quite long in life, but in the preserved state most of them were broken off and quite short. They bore occasion annulations. No nematocysts were found on the palpacle, but stenoteles were occasionally found scattered sparsely over the surface of the palpon itself. A maximum of six was observed. Mapstone (2004) mentioned a collar of nematocysts close to the distal tip of the palpon, but this was not observed on the palpons looked at during the present study.

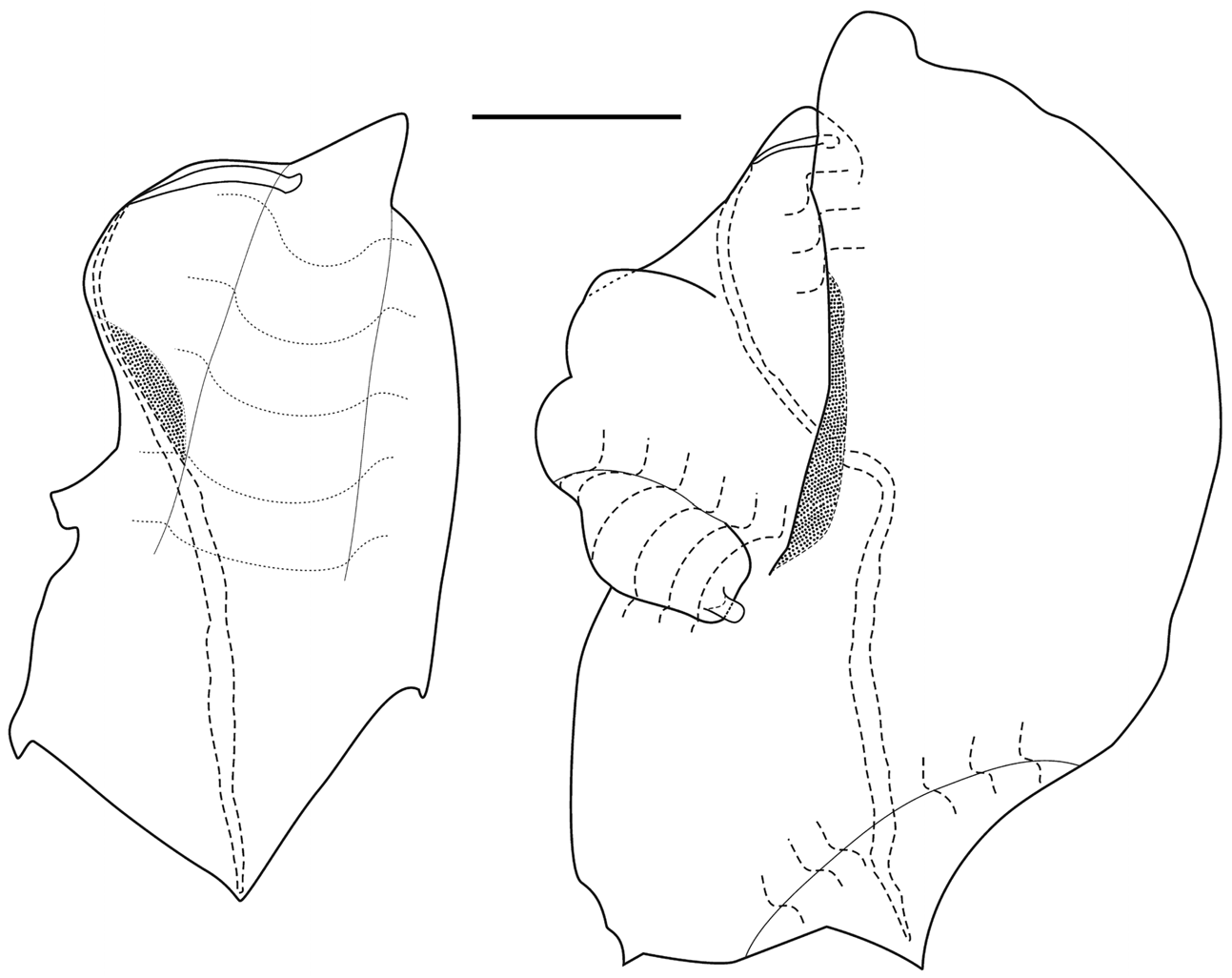

Gonophores: In each cormidium the male gonodendron ( Figure 75 View FIGURE 75 ) was attached to the siphosome immediately posterior to a gastrozooid, followed quite closely by the female one. The male gonophores, at various stages in development, appeared to be attached to a broad stalk, as noted by Huxley (1859), or at least a swelling from the siphosomal wall. Young palpons were also attached to this process. The female gonodendron, however, had a very distinct, elongate, thickened stalk ( Figure 75 View FIGURE 75 , sfg), with marked annular strengthening rings. Again the gonophores were at various stages in development, but no palpons appeared to be attached to the gonodendron.

Mapstone (2004) noted that this arrangement of the gonodendra in each cormidium differed from that of Halistemma rubrum , as described by Totton (1965), in that, for the latter species, there were three male gonodendra. However, she did not point out the more important difference in that in H. rubrum the female gonodendron was anterior to the male ones, while in H. foliacea the single male gonodendron was anterior to the female one.

The mature male gonophores measured up to c. 3 mm in length and were narrow cylindrical structures borne on short stalks. The female ones were broader and shorter ( Figure 76 View FIGURE 76 ). Mapstone (2004, p. 237) mentioned "four small tentacular buds" around the ostium of both the male and female gonophores, which in the former case at least contained nematocysts. This is in line with Huxley (1859, p. 73) who said "The calyx of the androphore is terminated by four obtuse elevations, containing large thread-cells", although he neither described nor illustrated such elevations on the female gonophores. Similarly, Bigelow (1911) described and illustrated tentacular rudiments around the ostium of the male gonophore, but made no mention of such on the female gonophores. Many of the gonophores, of both sexes ( Figure 76 View FIGURE 76 , A), did not show these knobs, but the most mature ones did ( Figure 76 View FIGURE 76 , B,C). They were four small excrescences around the distal ostium, although they do not appear tentacular as Mapstone (2004) suggested. Each of these contained up four or five stenoteles, measuring c. 70 x 20 µm.

Nectalia stage : The post-larval Nectalia stage of Halistemma foliacea has yet to be collected or identified.

Remarks. As noted in the Introduction, the species Stephanomia amphytridis was first illustrated by Lesueur & Petit (1807). Further descriptions, under the name S. amphitridis , were given by Huxley (1859), Bigelow (1911) and Kawamura (1954); but were all based, like the original illustration, on only siphosomal fragments. Mapstone (2004) published what she said was "The first full description of … Halistemma amphytridis ", based on a specimen that was fairly complete, including the nectosome and nectophores. Kawamura had compared his material with that of Bigelow, and Mapstone did the same for her specimen, and it was clear that they all belonged to the same species. This can be further proven by the fact that the late Frances Pagès re-examined Kawamura's material and produced some preliminary drawings ( Figure 77 View FIGURE 77 ) of the "ventral" bracts that had the same characteristic lateral indentation. A comparison of the illustrations of Bigelow and Mapstone with those of Huxley also shows that Huxley's specimen belonged to the same species.

However, do all these specimens belong to the species Stephanomia amphytridis? As we have already discussed in the Introduction it is our contention that none of the specimens mentioned in the previous paragraph belong to S. amphytridis and that should all be referred to as Halistemma foliacea .

Halistemma foliacea shows several distinctive characters that make it easy to identify. The presence of two vertical lateral ridges on the nectophores is a unique character among Halistemma species , as is the presence of a distinct keel on the lower side of all types of bract. The distinct semicircular incision on the inner side, in the distal half, of the "ventral" bracts is also a unique character.

During the present study of the same material as that which Mapstone (2004) described a few differences have emerged. The fact that Mapstone described the nectophores as being budded off on the ventral side of the nectosome was clearly an oversight on her part, as in all agalmatids with the exception of species of the genus Athorybia , which do not develop them, the nectophores are budded off on the dorsal side. However, this fact was not fully established until after her publication, by Dunn et al. (2005a), and further by Pugh (2006). Although Mapstone noted differences among the "lateral" bracts she did not clearly divide them into two types; perhaps to stay in line with Bigelow (1911). None the less, it is clear that there are two types distinguished by the presence/ absence of a deeply excavated area on the proximal, upper, inner surface of the bract. Mapstone also seemed to believe that patches of nematocysts were present at the distal end of the bracteal canal in all forms of bracts, but no evidence for this could be found for all but the "dorsal" ones. In that case the nematocysts were aggregated into a spherical ball extending from the distal tip of the bract but it was usually broken off and could only be seen on the youngest forms.

Distribution. As noted above, there appear to be only five known records for Halistemma foliacea . Quoy & Gaimard's (1833, ( 1834)) original specimen was collected to the north of New Guinea, in the equatorial region between 135 and 145°E. Huxley's (1859) specimen was collected off the east coast of Australia, for which Mapstone (2004) gives the position as 32°S, 155°07'E, almost half way between Sydney and Brisbane. Neither of these specimens is thought to be still in existence. However, Bigelow's (1911) specimens are housed at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. and were collected in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean at c. 17°S, 100.7°W (St. 4704) and 15°05'S, 99°19' W (Station 4705) during the ‘Albatross’ Expedition 1904–1905. Kawamura's (1954) small specimen was from Misaki, Japan and the one from Snellius Expedition (St. 317a at 7°55.0'S, 122°12.5'E) from north of Flores Island, Indonesia.

Dr Dhugal Lindsay (personal communication) has informed us that he found Halistemma foliacea to be common in the northern part of the Coral Sea; quite close to where Huxley collected his specimen. Thus the known specimens have all been found in the Pacific Ocean and, apart from Bigelow's specimens, within a somewhat restricted area. However, is probably has a much wider distribution and, because of the distinctiveness of its bracts, particularly the "ventral" ones, and the presence of two complete vertical lateral ridges on the nectophores, it should be easy to identify.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Halistemma foliacea

| Pugh, P. R. & Baxter, E. J. 2014 |

Halistemma foliacea

| Pugh, P. R. 2006: 42 |

Halistemma amphytridis Mapstone, 2004 , p. 232

| Mapstone, G. M. 2004: 232 |

Stephanomia amphitridis

| Kawamura, T. 1954: 110 |

Phyllophysa squamacea Haeckel, 1888b , p. 225

| Haeckel, E. 1888: 225 |

Stephanomia nereidum

| Haeckel, E. 1888: 221 |

Phyllophysa foliacea L. Agassiz, 1862 , p. 368

| Bedot, M. 1896: 399 |

| Haeckel, E. 1888: 40 |

| Agassiz, L. 1862: 368 |

Stephanomia foliacea

| Bedot, M. 1896: 384 |

| Haeckel, E. 1888: 225 |

| Huxley, T. H. 1859: 136 |

| Lamarck, J. B. P. 1840: 28 |

| Blainville, H. M. D. de 1834: 119 |