Cephalopachus bancanus (Horsfield, 1821)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6631893 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6631834 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CA4CA666-FFFC-9C3D-FFFF-FE6B7BE5F547 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Cephalopachus bancanus |

| status |

|

Western Tarsier

Cephalopachus bancanus View in CoL

French: Tarsier de Horsfield / German: \Westlicher Koboldmaki / Spanish: Tarsero de Horsfield

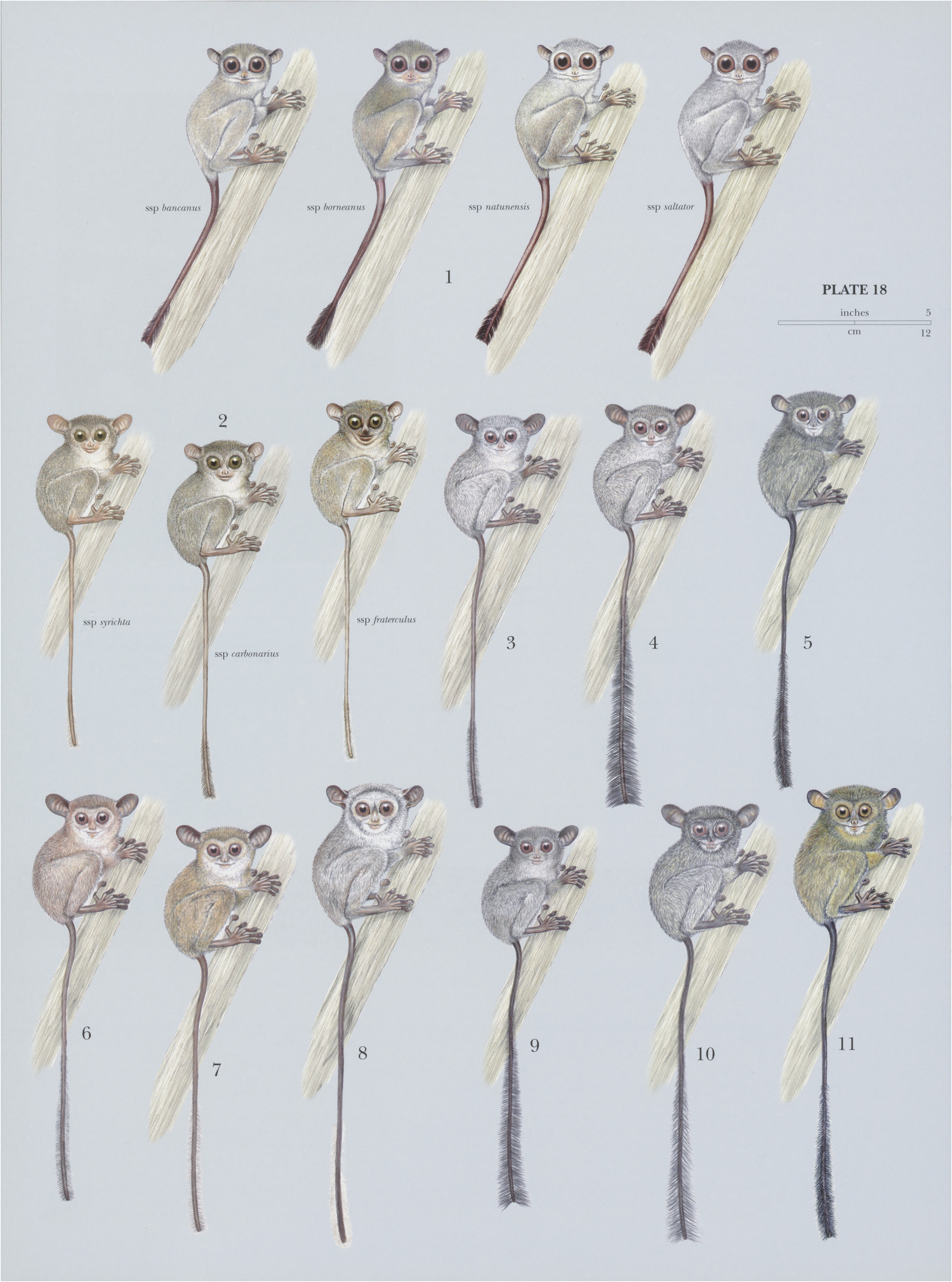

Other common names: Belitung Tarsier (saltator), Bornean Tarsier (borneanus), Horsfield's Tarsier (bancanus), Serasan Island / South Natuna Islands Tarsier (natunensis)

Taxonomy. Tarsius bancanus Horsfield, 1821 View in CoL ,

Indonesia, SE Sumatra, Bangka Island.

Western Tarsiers require a systematic review, giving particular attention to the form borneanus on Borneo. In 2008, A. Gorog and M. Sinaga reported an unusual montane form captured at Bukit Baka, western Kalimantan, at 1200 m above sea level. Behavioral differences of tarsiers in Sarawak and Sabah may also indicate distinct taxa. Many taxonomists do not recognize the subspecies natunensis and saltator, but Brandon-Jones and others included them as “doubtful” taxa that required further investigation. Their rationale was that Western Tarsiers are a group in need of taxonomic revision, and the analyses of museum specimens that were used to synonymize these two taxa were an inadequate basis for making ajudgment. Four subspecies recognized.

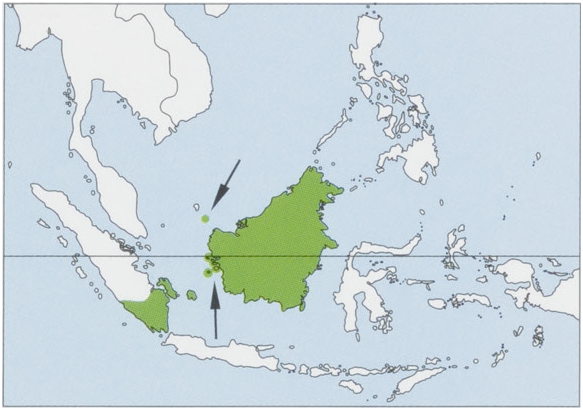

Subspecies and Distribution.

C.b.borneanusElliot,1910—BorneoandKarimataI(offtheSWcoastofBorneo).

C. b. saltator Elliot, 1910 — Belitung I. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 11.4-13.2 cm, tail 20-23 cm; weight 110-138-5 g (males) and 100-119 g (females). The Western Tarsier is characterized by having relatively larger eyes, shorter ears, longer hindlimbs and longer hands, when compared with other tarsiers. The skull appears relatively broader, in part because of its heavily flared eye sockets. Descriptions of pelage coloration are confounded by fading that occurs in museum specimens and captive specimens that are housed in enclosures that lack access to natural sunlight. The few color photographs of Western Tarsiers seem to indicate that the “Bornean Tarsier” (C. b. borneanus) has a dorsal coat thatis dark gray and rufous brown, rathertypical for many tarsiers, whereas the tarsiers from Sumatra (“Horsfield’s Tarsier,” C. b. bancanus ) have distinct yellow ochre tones that are unseen in other tarsiers. There is a dark spot on each knee. The facial mask is far less vivid than in the eastern tarsiers (7arsius), lacking the black paranasal spots and white paralabial fur. Neither are there post-auricular white spots. As with other tarsiers, the ventral coat is lighter, whitish to buffy. The tarsus is haired, but the feet are not. The tail is relatively shorter than all othertarsiers, and absolutely shorter than all tarsier species except the Sulawesi Mountain Tarsier ( Tarsius pumilus ), which may be a pygmy tarsier. Average tail length is 202 mm (n = 37). Thetailskin is dark red-brown. It is sparsely haired dorsally and naked ventrally. On the ventral surface near the base there is a small dermal skin composed of alternating ridges and “V’shaped grooves that act as a sitting pad when the tarsier clings in a vertical posture. Like all tarsiers, there is a tail tuft at the distal end. In Western Tarsiers the terminal tuft is light brown and sharply delimited, typically less than 25% of the distal end of the tail. There are very few comparative data with which to describe the “Belitung Tarsier” (C. b. saltator) and the “Natuna Islands Tarsier” (C. b. natunensis) and it is possible that the first is a synonym of bancanus, while the second could be a synonym of borneanus. Given the cryptic nature of tarsier alpha taxonomy, it is also possible that systematic phylogeographic study could reveal a completely different and utterly unexpected taxonomy.

Habitat. Historically, areas of South-east Asia that have tarsiers today were mostly covered in tropical rainforest, and there are no comparative data that directly evidence differences in habitat preference among extanttarsiers, with the exception of the Sulawesi Mountain Tarsier. Where tarsiers have been studied, they are found in virtually all habitats except urban areas and areas of intensive agriculture that are bereft of all potential sleeping sites or where pesticides are commonly used. Reports of Western Tarsiers come mostly from low-lying primary and secondary dipterocarp and coastal forest. They are often seen in forest and plantation edges. Individuals spend the majority of their time in the understory below 2 m and only 5% above 3 m. The elevational distribution of lowland tarsier species may vary, and until recently, almost all accounts of Western Tarsiers were below elevations of 100 m. Recently a tarsier capture was reported from 1200m but it also occurs in some highland areas (e.g. up to 1450 m above sea level in Bukit Baka-Bukit Raya National Park, Borneo. Photographs of the specimen evidence an unusual morphology and this may represent a distinct montane taxon, such as is found on Sulawesi.

Food and Feeding. All tarsiers are 100% carnivorous and eat only live-caught animal prey. There are no data that allow for direct comparisons of diet among species; thus is not known if reported differences in diet are due to availability, sampling, or actual differences. The Western Tarsier is reported to eat mainly insects, including beetles, grasshoppers, cockroaches, moths, butterflies, mantids, ants, phasmids, and cicadas. It will also eat small freshwater crabs, frogs, lizards, birds, bats, and even highly venomous snakes such as the banded Malaysian coral snake (Calliophis intestinalis).

Breeding. A menstrual cycle lasting about 24 days has been observed and measured in all three tarsier genera, and it is likely that this is common for all tarsier species. Likewise, seasonal birth peaks have been noted in several wild tarsier populations. It is likely that all tarsiers are capable of year round breeding, but have birth peaks that correspond to seasonal increases in resource availability. There are no direct comparative data that evidence any major difference in this pattern. In Borneo, there is reported to be a single birth peak, with mating from October to December and births from January to March. Courtship includes much chasing and vocalizing. An elaborate courtship ritual has been reported for Western Tarsiers that involves the female suspended by her forelimbs from a horizontal branch, while raising her legs and spreading them to either side, exposing her swollen red vulva, which is sharply contrasted against her light abdominal fur. A single young is born after a gestation of 178-180 days. As with all other tarsiers for which there are data, Western Tarsierscarry their young with their mouth. An individual lived for 17 years and seven months in the Cleveland Zoo, USA.

Activity patterns. As with all other tarsier species for which there are data, the Western Tarsier is nocturnal and arboreal. Activity begins shortly before sunset and ends around sunrise. There are activity peaks in the early evening and just before sunrise that are associated with feeding.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The best evidence is that Western Tarsiers live within a solitary-but-social, “noyau” (nucleus or kernel) social system. Females have a nearly exclusive home range that is overlapped by those of one or more males. Direct contact between the sexes is very rare, except for courtship and mating. Population densities have been variously calculated at 80 ind/km? in Sarawak and 15-20 ind/km* in Sabah. The subspecies saltator was estimated to occur at a density of 19-20 ind/km?* at a site on the island of Belitung.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Western Tarsier is protected by law in Indonesia and Malaysia. Its principle threats are habitat loss due to forest conversion, especially due to expanding oil palm plantations,fires, and logging, and in some areas, hunting and live capture for the (illegal) pet trade, particularly in southern Sumatra’s Way Kambas National Park and the entire Lampung Province. The Horsfield’s Tarsier occurs in ¢.85,000 km? in southern Sumatra and c.13,400 km* on Bangka, but massive forest loss throughoutits range resulted in its classification as Endangered. The Natuna Islands Tarsier occurs in only ¢.90 km” on the island of Serasan, and its population is assumed to be declining, with forest loss and degradation being the drivers.It is reasonable to expect that these losses are, at least in part, due to the exploitation of the Natuna gas fields. It is classified as Critically Endangered. Although wide-ranging, and believed to have originally occurred throughout the island of Borneo, the Bornean Tarsieris classified as Vulnerable because of the massive forest loss on Borneo, most especially in Kalimantan, since the 1980s, due to logging, land clearing for plantations, and forest fires. It is possible that distinct species or subspecies may yet to be discovered on Borneo, which would reduce the supposed geographic distribution of borneanus and modify its threatened status. The Belitung Tarsier only occurs in 5625 km?* on the island of Belitung, evidently limited to the center ofthe island;it is classified as Endangered. The Horsfield’s Tarsier occurs in three Sumatran national parks: Bukit Barisan Selatan, Kerinci-Seblat, and Way Kambas. The Bornean Tarsier occurs in ten protected areas: Tasek Merimbun Widlife Sanctuary in Brunei; Bukit Baka-Bukit Raya and Kayan Mentarang national parks in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo; and Bako, Gunung Mulu, and Kinabalu national parks and Danum Valley Conservation Area, Sapagaya, Semengo, and Sepilok forest reserves in Malaysian Borneo. The Belitung and Natuna Islands tarsiers do not occur in any protected areas.

Bibliography. Crompton & Andau (1986, 1987), Crompton et al. (1998, 2010), Fogden (1974), Gorog & Sinaga (2008), Groves (2001), Gursky (1997, 1999), Gursky et al. (2008), Haring et al. (1985), Harrison (1962, 1963), Hofer (1979), Izard et al. (1985), Jablonski & Crompton (1994), Niemitz (1973a, 1973b, 1974, 1979a, 1979b, 1983, 1984a, 1984b, 1984d, 1984e), Poorman et al. (1985), Roatch et al. (2011), Roberts (1994), Roberts & Cunningham (1986), Roberts & Kohn (1993), Schmitz et al. (2001, 2002), Van Horn & Eaton (1979), Wright, Izard & Simons (1986), Wright, Toyama & Simons (1986).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.