Adeonella pallasii ( Heller, 1867 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222931003760061 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/FB2D9A7D-A440-EE32-FE2B-FF7D7994A9E7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Adeonella pallasii ( Heller, 1867 ) |

| status |

|

Adeonella pallasii ( Heller, 1867) View in CoL

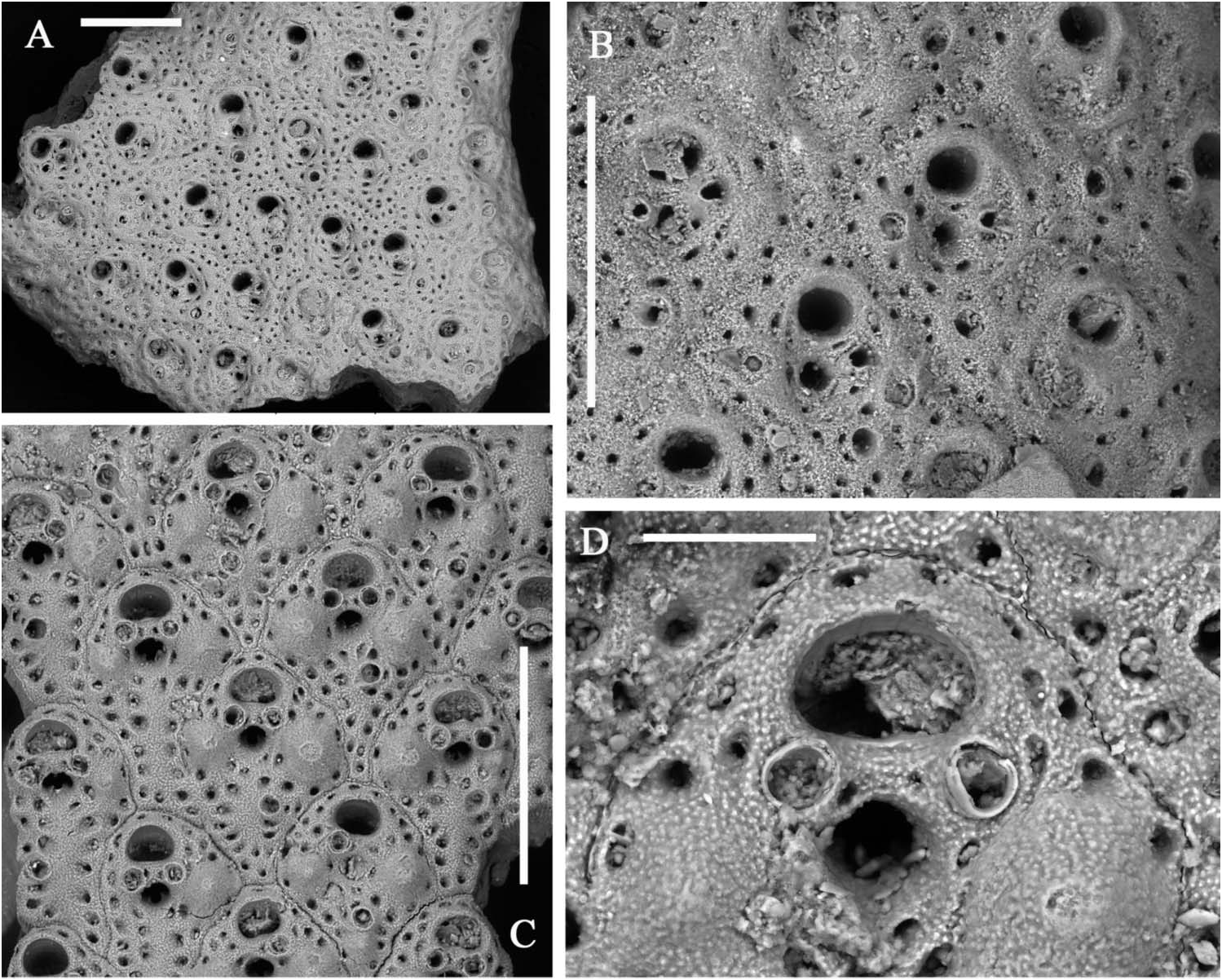

( Figures 1E View Figure 1 , 4B View Figure 4 , 5–7 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 )

Eschara pallasii Heller, 1867: 115 View in CoL , pl. 3, figs. 1,2.

Schizoporella pallasii: Hincks, 1886: 268 , pl. 10, fig. 7.

Adeonella polystomella: Harmelin, 1969: 301 View in CoL , figs. 6: 2-3; Zabala and Maluquer, 1988: 144, fig. 160; Di Geronimo et al. 1992: 236; Zavodnik et al. 2000: 162.

Adeonella pallasii: Ünsal and d’Hondt, 1978 View in CoL –79: 622, figs. 3,4; Hayward, 1988: 171, fig. 23C,D; Di Geronimo et al., 1998: 250; Novosel and Požar Domac, 2001: 377; Hayward and McKinney 2002: 44, fig. 20 A–E; Novosel et al., 2004: 162; Novosel, 2005: fig. 2; 2007: 189.

Examined material

Holocene. Northern and central Adriatic Sea : several living colonies and colony fragments from the Novosel collection housed at FSUZ , collected from 1998 to 2008 and originating from coralligenous communities off the following Croatian islands and islets: Kornati : 5–45 m; Prvić : 5–30 m; Lastovo : 5–45 m; Jabuka : 5–45 m; Silba : 10 m; Ćutin : 12–30 m; Dugi Otok : 5–40 m; Brusnik : 10–20 m; Biševo : 4–30 m; Vis : 5– 40 m; Palagruža : 10–35 m; Sušac : 10–20 m; Mljet : 15–40 m; Korćula : 15–30 m; Jabuka Shoal : 10–50 m; Pelješac Peninsula : 10–25 m and Velebit Channel : 10–30 m. Southern Adriatic : Apulian shelf (Bannock, 1971 cruise: a few dead fragments from two stations: 80–100 m. PMC. R.I.H. B7a). Ionian sea: Amendolara Bank 1991 (a few living and hundreds of dead specimens from two samples: 40–50 m, DC; very rare to some hundreds of dead fragments from some samples: 23–60 m, C, DC and SGCF. PMC. R.I.H. B7b); off Porto Cesareo (a few living and dead specimens: 17 m. PMC. R.I.H. B7c). Aegean Sea : a few living fragments from the Harmelin Collection originating from the Strait of Scarpanto, “Jean Charcot” Expedition, st. 19.MO.67, 29 August 1967, 35°55′ N, 27°28,50′ E, 29–33 m. PMC.H. Greece.H.B7d. Some living fragments from the Harmelin-Bitar Collection (2 May 2001) originating from Lebanon, Selaata, near Batroun, 32 m. PMC.H. Lebanon.H.B7e. Early Pleistocene: Fiumefreddo quarry (north-east Sicily): some fragments from a single sample. PMC. R GoogleMaps . I.Ps. B 7f. Tortonian–Early Messinian : Benestare: a few specimens from a single sample, PE community. PMC. R .I.M.B 7g.

Further material as Adeonella sp. : Early Pleistocene: Calabria, southern Italy (Musalà section: 16 reworked specimens); Lazzàro section (some fragments from two samples, DC-SGCF transitional assemblages, inferred depth 40–50 m). PMC. R.I.Ps.B8a. Early to Middle Pliocene: Calabria, southern Italy (Pavigliana section: few to some fragments from five samples, DC biocoenosis and DC-SGCF, DL- VP transitional assemblages, inferred depths from 40 to 180 m). PMC. R.I.Pl.B8b. Late Tortonian-Early Messinian: Calabria, southern Italy (S. Onofrio section near Vibo Valentia: some specimens from some samples). PMC. R.I.M.B8c.

Description

Colony light orange, erect, with fragments up to 3.5 cm high and 3.5 cm across, in the present material ( Figure 1E View Figure 1 ), but living colonies can be massive and reach up to 20 cm in height. Branches, bifurcating at sharp angles, locally anastomosing and twisting, about 1 mm thick and usually 2–3 mm wide, reaching 5 mm before bifurcations; bilaminar, including up to 10 rows of alternating zooids on each side ( Figure 5A,B View Figure 5 ).

Autozooids intumescent, rhomboidal, with a rounded enlarged distal portion and a narrow, often pointed proximal end in the central rows ( Figures 5D,E View Figure 5 , 6B,D,G View Figure 6 ; 7B,C View Figure 7 ); larger and subrectangular in the two marginal rows from each side ( Figures 5A View Figure 5 , 6A View Figure 6 ); distinguished by deep grooves and a median raised suture. Frontal shield finely granular and swollen, mostly in the distal half, pierced by one continuous row of distinct evenly spaced areolar pores, plus a few others from around the orifice and the spiramen, larger in early ontogeny. Paired suboral marginal tubercles and a third proximal tubercle may develop in early ontogeny, mostly on the central zooids ( Figures 5D,E View Figure 5 , 6G View Figure 6 ; 7C View Figure 7 ). Primary orifice as wide as long with a straight proximal border and a large U-shaped sinus ( Figure 5I–L View Figure 5 ). Condyles lateral, angular, small but robust. Secondary orifice transversely elliptical to circular, with an inner short subtriangular proximal process ( Figure 5E View Figure 5 ). Spiramen relatively large, subcircular to transversely oval, usually leaving visible the oral sinus in all but the latest ontogenetic stages ( Figures 5D,E View Figure 5 ; 6D,G View Figure 6 ); separated from the secondary orifice by a stout bridge of calcification. Peristomial avicularium small, single or paired ( Figures 5D,E View Figure 5 , 6D View Figure 6 ), often lacking in some zooids, mostly in the central rows, but showing no differentiation on marginal zooids ( Figure 5C View Figure 5 ); situated on the spiraminal bridge, coaxial and converging towards the middle or gently inclined to the spiramen, rarely proximally directed; rostrum subtriangular to subelliptical. One to rarely two or even three, variably oriented, frontal adventitious avicularia, comparable in shape and size with the peristomial ones, sporadically develop on some senescent zooids ( Figures 5F View Figure 5 , 6A–E View Figure 6 ). Frontal shield thickens with ontogeny becoming more and more swollen, secondary orifice sinking far below the frontal surface ( Figure 6C View Figure 6 ). Sutures may be obliterated giving the branch a smooth appearance. During late stages even orifices become occluded and frontal tubercles become concealed. Vicarious avicularia and gonozooids not observed and seemingly absent. Kenozooids lacking orifice but with a small avicularium comparable in shape and size to the peristomial ones, occasionally present at bifurcation axils ( Figure 5G View Figure 5 ). Encrusting base formed by kenozooids with or without small subtriangular avicularia.

Measurements

ZL: 545 ± 42.32, 482–645 (3, 30); ZW: 446 ± 38.03, 382–527 (3, 30); sOL: 91 ± 12.85, 68–110 (3, 30); sOW: 124 ± 12.99, 103–146 (3, 30); AL: 69 ± 8.02, 54–80 (3, 17); AW: 39 ± 5.28, 28–48 (3, 17).

Remarks

A lectotype for A. pallasii has been recently chosen and figured by Hayward and McKinney (2002) from among Heller’s type specimens. The species appears well characterized by the general aspect of the distally prominent swollen zooids, the morphology of the primary orifice, and the position of the usually transversely oriented peristomial avicularia (see Hayward and McKinney 2002). In contrast, the presence of additional frontal adventitious avicularia is neither reported nor apparent on the figured specimens. Nevertheless, such avicularia can be present, although not frequently, on some zooids from the proximal region of some branches. Of note is that the avicularium seems

the southern Adriatic. Note the heavy frontal calcification and the deepening of orifice and spiramen. Scale bar: 500 µm. (G,H) Living specimen from the Lebanon, Recent, overhang, 32 m. (G) Some zooids from a slender branch. Scale bar: 500 µm. (H) Detail of the paired peristomial avicularia touching in the mid-line of the peristomial bridge. Scale bar: 100 µm .

to be single on a few zooids from Adriatic populations ( Figures 5F View Figure 5 , 6A–C View Figure 6 ) whereas two or three diversely oriented frontal avicularia can be seen on several zooids from the Scarpanto area population ( Figure 6D,E View Figure 6 ), always in the proximal periphery or sometimes near the spiramen. Due to this feature, specimens from the Aegean Sea were referred by Harmelin (1969: 301) to A. polystomella ( Reuss, 1848) , although uncertainties derived from the position and the direction of the peristomial avicularia. Adeonella polystomella is a species morphologically similar to A. pallasii with which it seems to have been confused in the past, as already remarked by Hayward (1988) and Hayward and McKinney (2002) or even synonymized ( Zabala 1986). Nevertheless, when living or dead wellpreserved specimens are considered, A. polystomella can be distinguished by its stronger colony, elongated zooids, the different proportion of the primary orifice, and the usually spaced, distally or proximally directed peristomial avicularia (cf. Rédier and d’Hondt 1976; Ünsal and d’Hondt 1978–79; Hayward 1988). In addition, the secondary orifice tends to be transversely oval or bean-shaped and the condyles are longer and inclined centrally, the marginal areolae larger, as well as frontal avicularia.

In contrast, a confident identification of dead and especially fossil fragments is difficult because of their usually poor preservation state. Specimens are nearly always worn and features such as peristomial and frontal avicularia are often reduced to mere round pores. Taking into account similarities between A. pallasii , A. calveti and A. polystomella and the problems related to fossil identification, it can therefore be argued that some material traditionally ascribed to A. polystomella could actually belong to A. pallasii (see also discussion for A. calveti ).

Finally, Hayward (1983: 588, fig 4C) recorded a further species, Adeonella sp. 1 , similar to A. pallasii but with a stouter colony, a proportionally larger orifice and a markedly triangular sinus. The status of this taxon from the Red Sea remains uncertain.

Variability and ecology

Variability in A. pallasii is mostly linked to the presence and number of the frontal adventitious avicularia, the proximal and lateral frontal knobs, and to secondary frontal calcification leading to the occlusion of orifices and spiramina evolving into deep depressions, sometimes coalescing to form a single pit. Furthermore, in late ontogeny zooids tend to become transversely rhomboidal but still remain separated by peripheral grooves ( Figure 6C View Figure 6 ). Such transformations give the basal branches a cylindrical, somewhat furrowed, shape. Further differences, including the persistence, size and position of the peristomial avicularia and the zooidal shape, have been observed between populations originating from different geographical areas. Of particular interest is the closeness of the paired peristomial avicularia, rigidly coaxial with the peristomial bridge, whose rostra touch at the midline, in specimens from the Eastern Mediterranean including the Aegean sea ( Harmelin 1969: fig. 6.2), and the Turkish (Ünsal amd d’Hondt, 1978–79: figs. 3-4) and Lebanese ( Fig. 6G,H View Figure 6 ) coasts.

Like A. calveti View in CoL , this species seems typical of hard bottoms from coralligenous biocoenoses ( Harmelin 1969; Novosel 2007), but it is also present in some reophilic facies of DC and even in SGCF biocoenoses ( Harmelin, 1969; Di Geronimo et al., 1998) in the shallow circalittoral zone (30–50 m). It has also been recorded in Cellaria View in CoL meadows (35 m) on silty sediments (McKinney and Jaklin 2001). Nevertheless, the species lives down to more than 100 m in some areas of the central-southern Adriatic and the Aegean Sea as reported for specimens from Lastovo ( Neviani, 1939) and from near Santorini and the Scarpanto Strait ( Harmelin 1969). Finally, A. pallasii View in CoL extends in shallower waters in overhangs and cave environments only 1 m deep ( Amui 2005; Novosel 2007 and personal observations).

Large fragments are fouled in their proximal parts by the foraminiferan Miniacina miniacea (Pallas, 1766) View in CoL , some spirorbids, gorgonaceans and other bryozoans, mostly Reptadeonella violacea (Johnston, 1847) View in CoL .

Distribution

Adeonella pallasii View in CoL is extremely common in the northern and southern Adriatic and also in the northern Ionian Sea, as suggested by present material and past records ( Heller 1867; Hincks 1886; Neviani 1939; Di Geronimo et al. 1998: Novosel and Požar Domac 2001; Hayward and McKinney 2002; Novosel et al. 2004; Amui 2005; Novosel 2007). The presence of the species in the eastern Mediterranean, discussed by Hayward (1988), is substantiated by records from the eastern Aegean Sea, from 30 to 130 m ( Harmelin 1969) and along the western Turkish coasts, from 40 to 60 m (Ünsal and d’Hondt 1978–79). Further colonies come from a 32-m deep overhang along the Lebanese coast (Harmelin, personal communication, 2008). The specimens recorded under the name A. polystomella View in CoL by Hayward (1974) but not figured, from less than 60 m around Chios Island, may also belong to this species.

In contrast, A. pallasii View in CoL seems absent from other western Mediterranean localities, apart from a single record from the Gulf of Naples by Hincks (1886), which needs to be substantiated (see Hayward 1988). The species has never been reported in comprehensive lists ( Gautier 1962; Harmelin 1976; Zabala 1986; Zabala and Maluquer 1988) from this sector and no specimen has been found after picking from a large number of samples from the Tyhrrenian and the western Ionian Sea. The presence of living A. pallasii View in CoL populations in the southern Mediterranean remains to be substantiated although it was probably present in the recent past as indicated by the finding of two worn fragments within sediments from a shallow submarine cave at Lampedusa Ile and a further few specimens from the Tripoli beach ( Libya) by Buge and Debourle (1977: pl. 10, fig. 2).

Adeonella pallasii View in CoL has been not recorded as fossil. Nevertheless, the studied material suggests that the species has been present in the Mediterranean area (at least in some sectors related to the modern Ionian Sea) since the Late Miocene. The earlier record from Benestare dates to the Late Tortonian–Early Messinian ( Di Geronimo et al. 1992). Other specimens confidently determined as A. pallasii View in CoL originate from Early Pleistocene sediments cropping out near Fiumefreddo (north-east Sicily). Material from southern Calabria, in part previously referred to A. polystomella View in CoL ( Barrier et al. 1987; Costa et al. 1991), cannot be confidently attributed to any species because of its poor preservation. The genus Adeonella View in CoL is otherwise widespread and common in the area and also in Sicily from the Late Tortonian onward. Similarly, the actual reliability of several fossil records from the Mediterranean area and from the nearby regions of both Europe and Africa needs to be checked after SEM re-examination of Reuss’s type material of A. polystomella View in CoL .

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Adeonella pallasii ( Heller, 1867 )

| Rosso, Antonietta & Novosel, Maja 2010 |

Adeonella polystomella:

| Zavodnik D & Jaklin A & Radosevic M & Zavodnik N 2000: 162 |

| Di Geronimo I & Rosso A & Sanfilippo R 1992: 236 |

| Harmelin J-G 1969: 301 |

Schizoporella pallasii:

| Hincks T 1886: 268 |

pallasii

| Heller C 1867: 115 |