Andricus truncicolus ( Giraud, 1859 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5296.2.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:030F54CC-5585-4FB1-ACEC-3592E6CF2C52 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7982611 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/F67F87A7-F567-FF9E-FF5F-F884FEC1718A |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Andricus truncicolus ( Giraud, 1859 ) |

| status |

|

Andricus truncicolus ( Giraud, 1859)

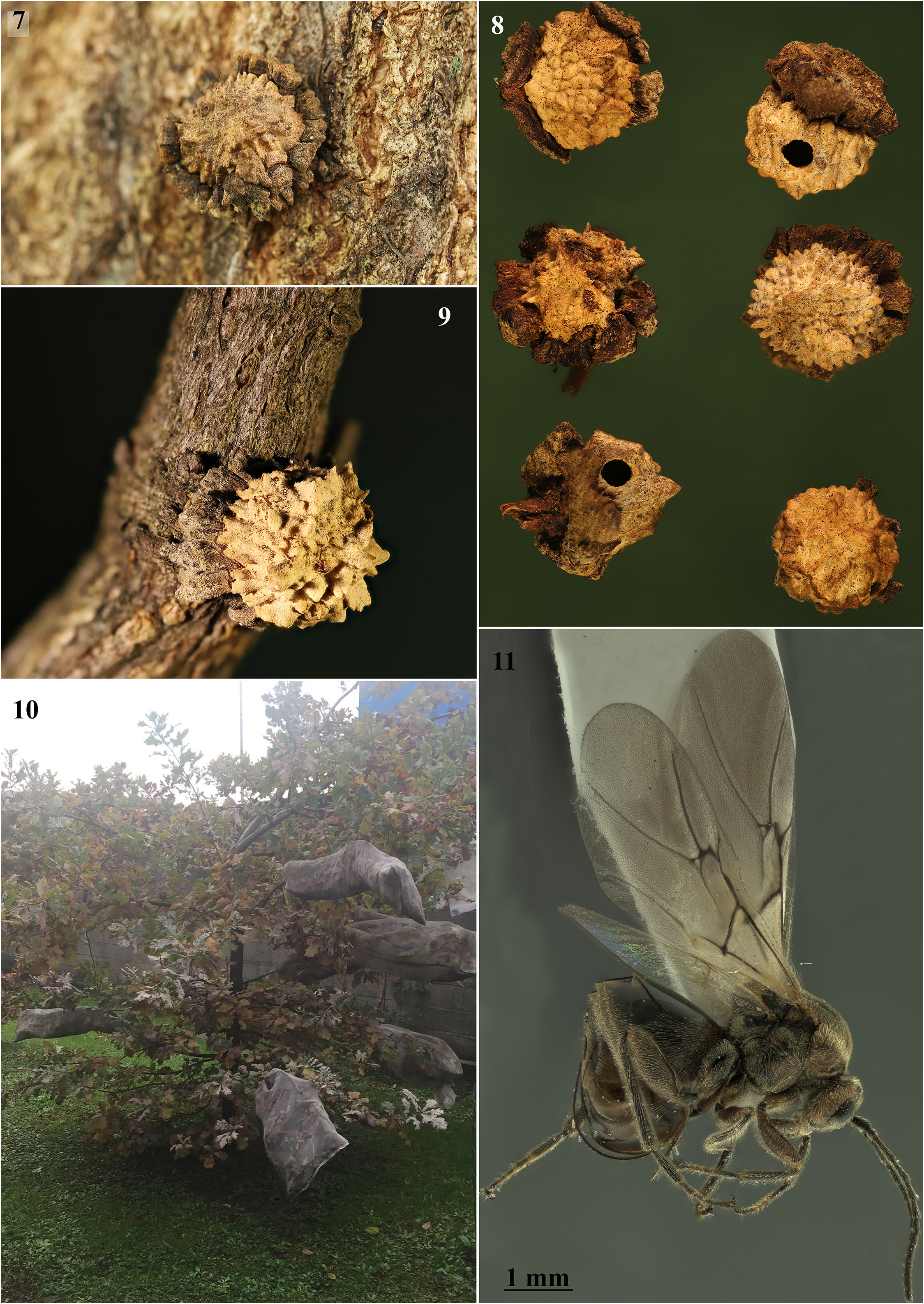

Asexual galls ( Figs 1–9 View FIGURES 1–6 View FIGURES 7–11 ). Asexual galls develop mainly on adventitious buds on trunks and large branches, on oaks of the section Quercus . They are monocular, usually solitary, rarely in clusters of two or three, the shape is sub-spherical (some specimens with indentation to form an apex towards the top) and similar to the seed cones of cypress trees, from 6 to 14 mm in diameter and attached with a robust short peduncle. During early development (about three–four weeks) the galls are succulent and spongy, covered on the surface by dense whitish pubescence that gives a velvety appearance ( Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1–6 ). The spongy tissue layer is deep red and covers the larval chamber ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1–6 ). During maturation the external spongy layer dries up (like a layer of clay dried in the sun) dividing into many more or less regular plates ( Figs 3, 5 View FIGURES 1–6 ). After drying, these plates take on a very similar color to the bark ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 1–6 ) and with exposure to atmospheric agents they easy detach, causing the partial ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES 1–6 ) or total revelation of the hard larval chamber ( Figs 7–9 View FIGURES 7–11 ). The gall remains strongly attached with its short peduncle to the trunk for several years. The larval chamber consists of a layer of about 1 mm of compact, woody tissue, whitish, with an irregular surface and small finger-like protuberances (protrusions of 1–3 mm) ( Figs 7–9 View FIGURES 7–11 ). It protects internal nutritive tissue and the larva during its development. The larva feeds on the nutrient tissue by burrowing into a large, regular, subelliptic chamber. Asexual female emerges from a lateral hole.

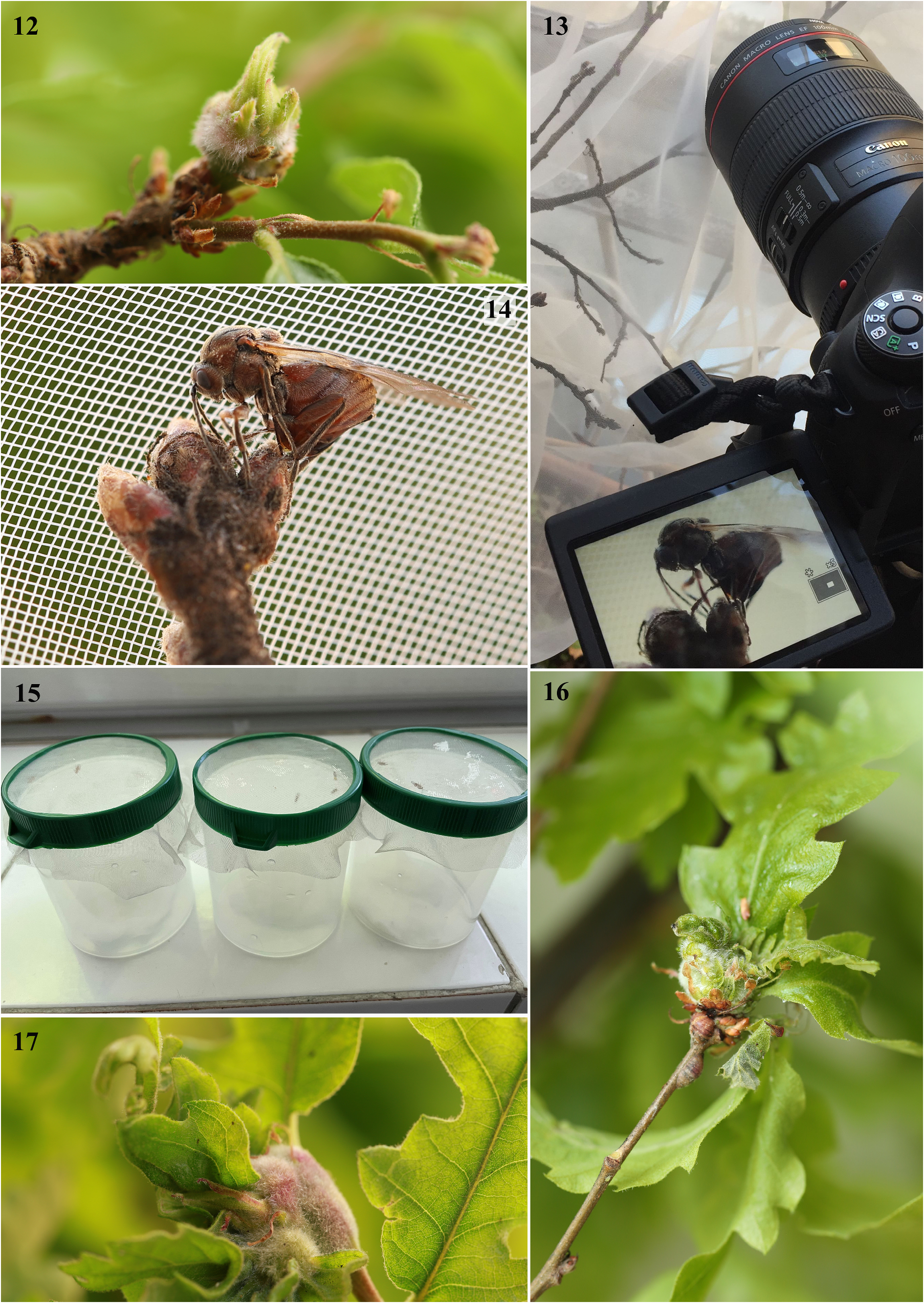

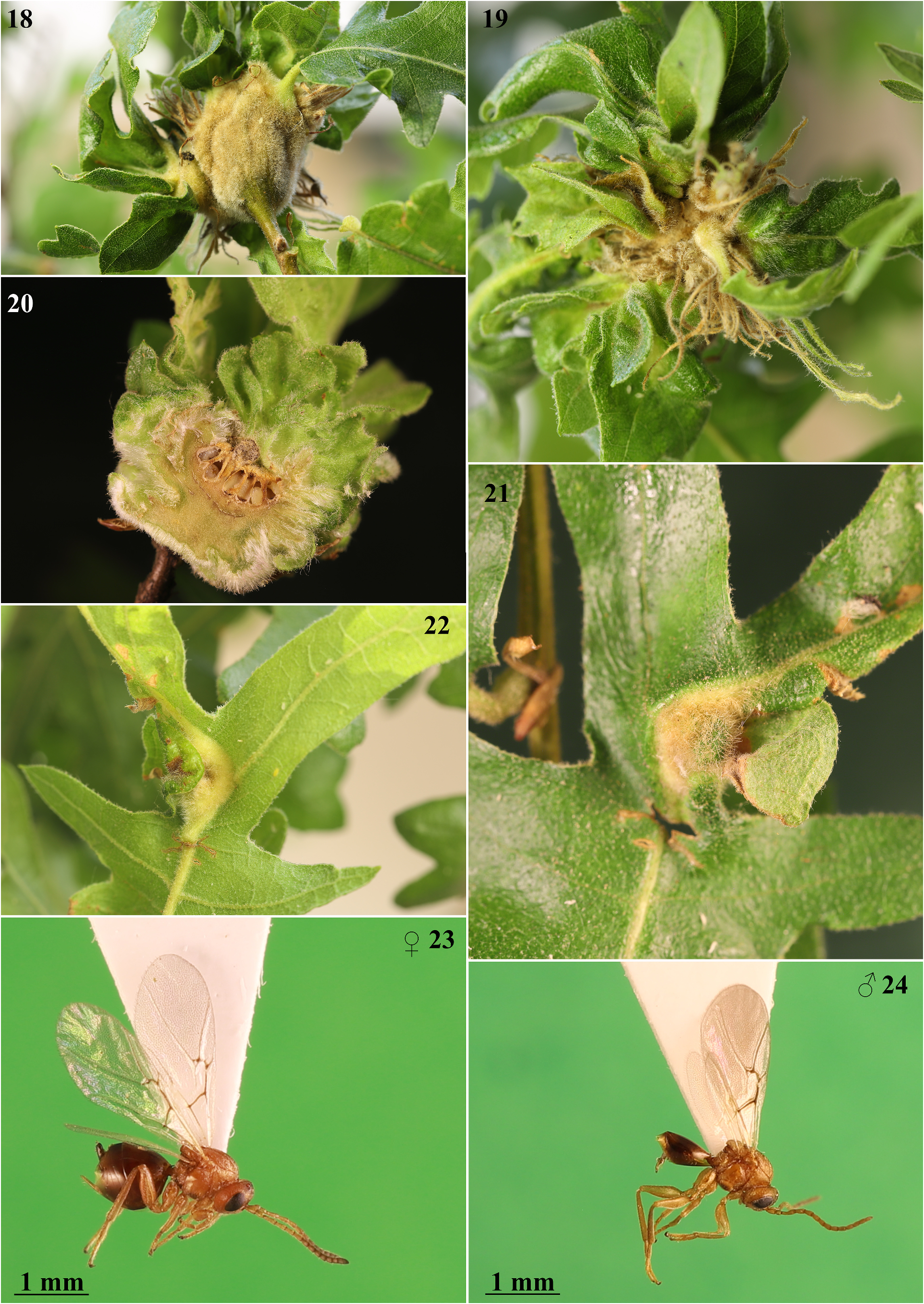

Sexual galls ( Figs 12, 16–22 View FIGURES 12–17 View FIGURES 18–24 ). The galls of the sexual generation developed on the terminal or lateral shoot buds of Q. cerris , exceptionally on the leaf blade, as found in only one case inside a contact chamber ( Figs 21, 22 View FIGURES 18–24 ). The galls consist of a hypertrophic tissue development resulting in an ovoid or subspherical swelling with a diameter that can vary from 10 to 40 mm (often the galls are coalescent, forming large conglomerates and reaching sizes greater than 50 mm); they are light-green when young ( Figs 16–17 View FIGURES 12–17 ) and dark-green and then brown when mature ( Figs 18–19 View FIGURES 18–24 ), bearing more or less deformed or normal leaves on the upper part.

The typical structure of the gall consists of a layer of compact vegetative tissue, 3 to 10 mm thick, which in shape resembles a more or less concave floral receptacle. This woody receptacle, sometimes closed like a ceramic pot, in other cases open like a plate, provides support and protection for the larval chambers (5 to 20) that develop above ( Fig. 20 View FIGURES 18–24 ). The surface of the gall receptacle is externally covered with soft hairs that confer a velvety, silvery appearance to the gall. On the receptacle, curled, rakish leaves and twigs develop, and in some of these, larval cells can migrate with the growing leaves during development; these metamorphosed leaves wither as the galls mature and after adult emergence the galls may remain on the plant for several years. The larval chambers are egg-shaped with an enlarged base and a more or less pointed and slightly curved apical extension, measuring 3.3–4.5 mm in height x 1.8–2.8 mm in width measured at 1/3 from the base. They develop cohesively, with each embedded in a socket of the supporting receptacle tissue like teeth in the gums. Sometimes the constrained proximity of the chambers alters their egg shape to rectangular parallel-sided with rounded corners. When the gall receptacle is open, the larval chambers are visible from above. In the inner part of the receptacle, the surface is coated with dense coverage of white hollow single-cell hairs; these structures in a less dense form coat the larval cells with a distinct supporting cell layer. Whitish hairs are longest at the base of the larval chamber and become shorter at the apex. The inner layer of the larval chamber is thin and hard, composed of sub-rectangular cells arranged longitudinally along the length of the chamber; the emergence hole is in the apical or sub-apical part.

Similar galls. Generally, on the basis of the characteristics and information on the gall and the host plant species, numerous gall-producing insects can be identified to the species level. However, some exceptions have recently been reported in gall wasps and gall midges ( Sottile et al. 2022). The asexual generation gall of A. truncicolus is similar to of Andricus megatruncicolus Melika, 2008 and when the galls are the same size it is impossible to distinguish them on the basis of the gall only. The asexual gall also resembles Andricus turcicus Melika, Mutun & Dinç, 2014 , but the available plates of the latter species consist of spiny protrusions. As detailed in Sottile et al. (2022) sexual generation galls of A. multiplicatus are very similar only to those of A. conificus sexual generation (= Andricus cydoniae Giraud, 1859 ). Both develop on the same host plants, as already has been pointed out by Giraud (1859), who, in the description of Andricus cydoniae , wrote: ‘II est facile de la confondre avec la galle d’ A. multiplicatus … Elle est toujours plus précoce, sa forme est mieux déterminée et elle n’est pas couverte des nombreux plis de la feuille qui distinguent cette dernière’. However, Sottile et al. (2022) did not find any macro or micro-morphological characters to distinguish the two galls with absolute certainty, concluding that it is impossible to identify the species only on the basis of gall morphology. However, species identification through adults is relatively easy on the basis of morphological differences involving body colour and sculpture, head and metascutellum measurements and ratios, and length of setae on prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium, as described by Sottile et al. (2022). The galls of the sexual generation of A. truncicolus that we have obtained experimentally are themselves indistinguishable from those induced by A. multiplicatus and A. conificus sexual generation, but even in this case morphological characters of the emerged adults allow identification of the inducer species.

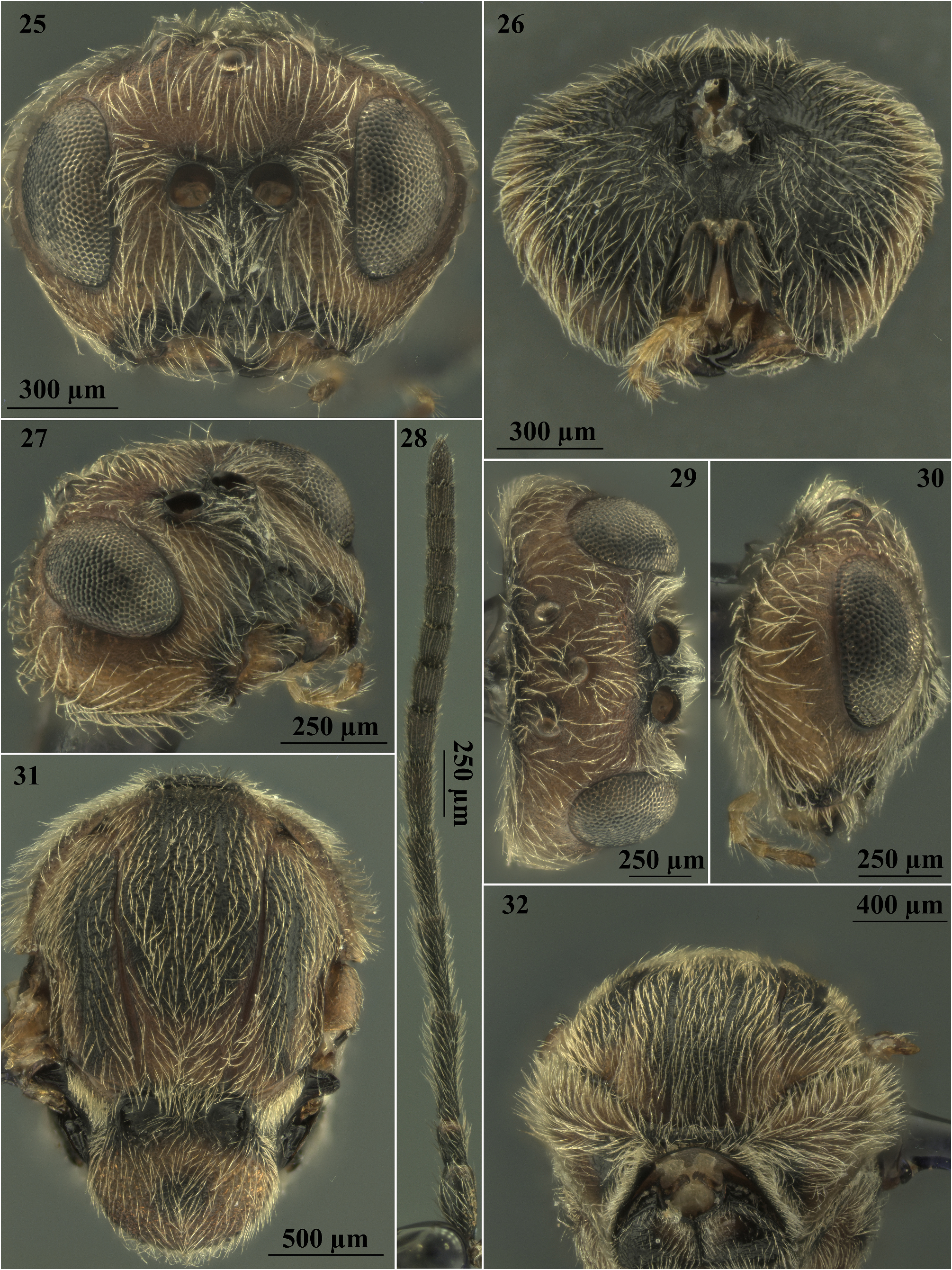

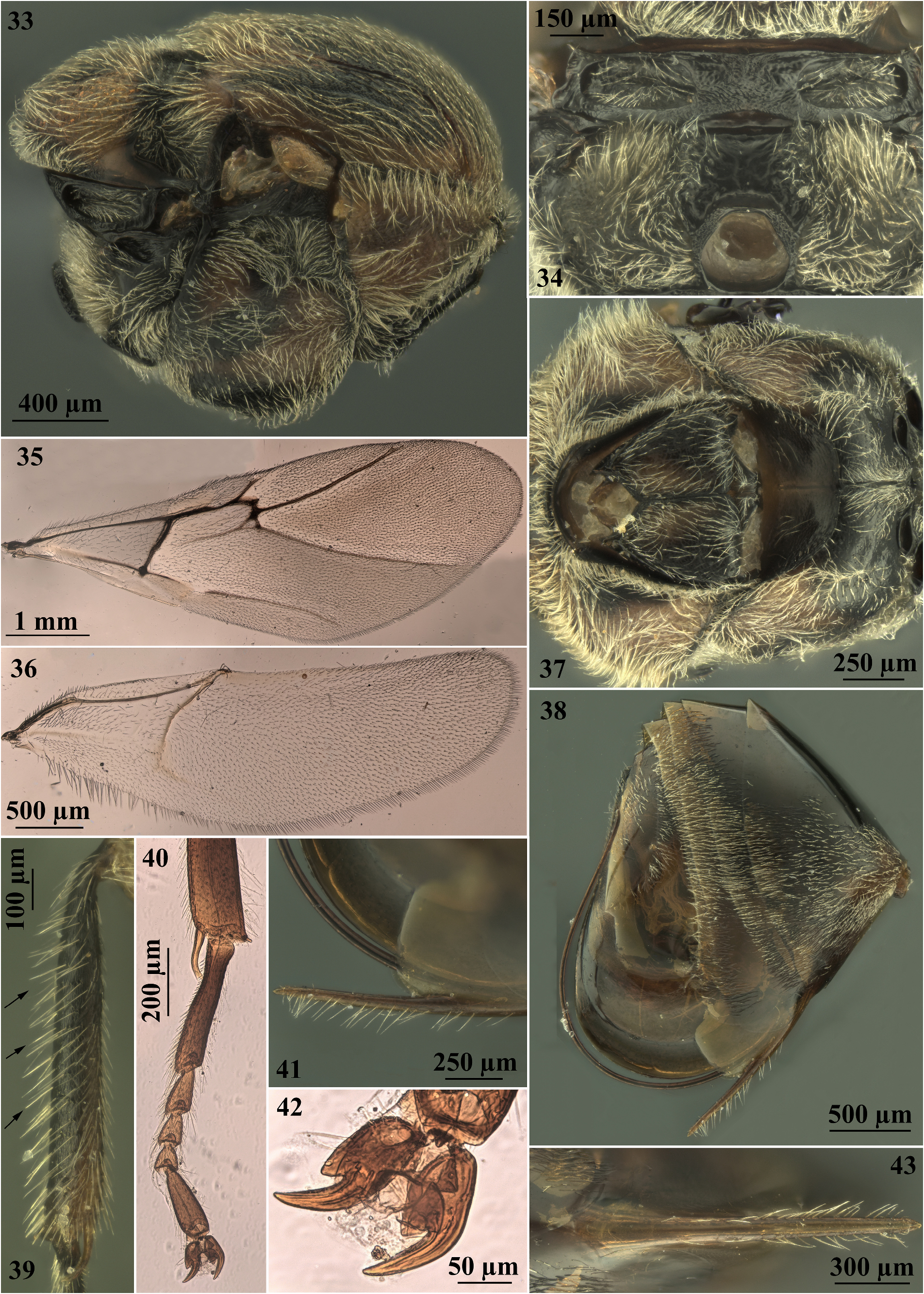

Diagnosis of the asexual form. Asexual females of A. truncicolus ( Figs 10 View FIGURES 7–11 , 25–43 View FIGURES 25–32 View FIGURES 33–43 ) belongs to “ Adleria - non kollari ” group, a large group of 13 Andricus species ( Pujade-Villar et al. 2015) with the anterior surface of foretibia bearing long oblique setae ( Figs 39, 40 View FIGURES 33–43 ); antenna 14-segmented (rarely 13 or 15) ( Fig. 28 View FIGURES 25–32 ), the mesoscutum coriaceous, without punctures ( Fig. 31 View FIGURES 25–32 ), all metasomal tergites with dense white setae laterally ( Fig. 38 View FIGURES 33–43 ) and the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium needle-like and very long ( Figs 41, 43 View FIGURES 33–43 ) ( Pujade-Villar et al. 2015).

More specifically in A. truncicolus the prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium is long and slender, 5.75–6.0 times as long as broad in ventral view, with relatively short setae ( Figs 41, 43 View FIGURES 33–43 ). It closely resembles A. conificus , from which differs for the following morphological characters described by Sottile et al. (2022).

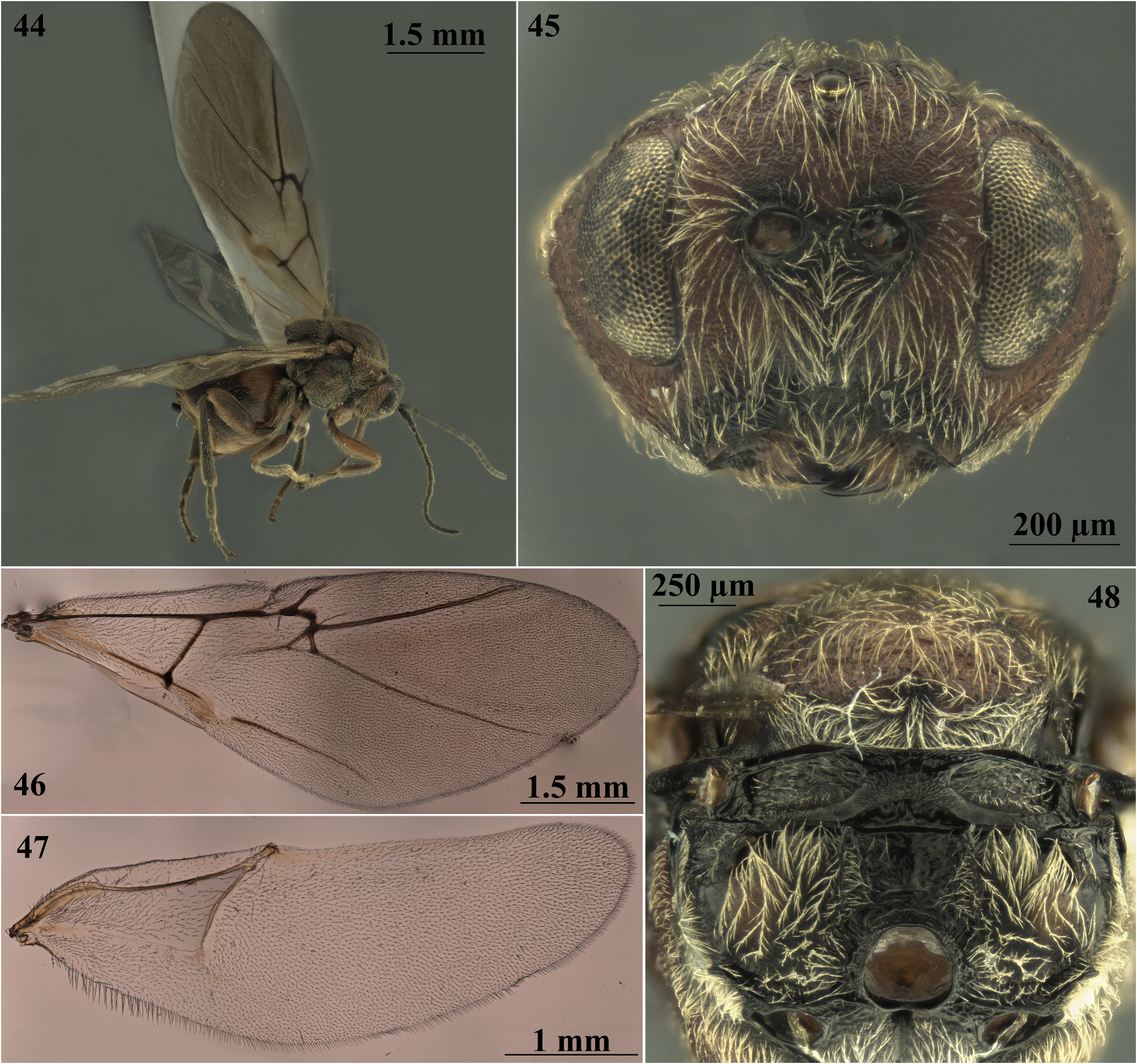

In A. truncicolus the body is blackish brown ( Fig. 10 View FIGURES 7–11 ), the head is more rounded in front view ( Fig. 25 View FIGURES 25–32 ) and the ratio between the transverse diameter of eye (measuring along the transfacial line) and the width of gena behind eye (measured at the same point)> 4.5 ( Fig. 25 View FIGURES 25–32 ), first abscissa of radius angled and projecting into radial cell ( Fig. 35 View FIGURES 33–43 ), metascutellum more than 3.2 times as high as height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum ( Fig. 34 View FIGURES 33–43 ), while in A. conificus ( Figs 44–48 View FIGURES 44–48 ) the body is reddish brown ( Fig. 44 View FIGURES 44–48 ), the head is trapezoid in front view ( Fig. 45 View FIGURES 44–48 ) and the ratio between the cross diameter of eye (measuring along the transfacial line) and the gena width behind eye (measured at the same point) <3.5 ( Fig. 45 View FIGURES 44–48 ), first abscissa of radius angled, not projecting into radial cell ( Fig. 46 View FIGURES 44–48 ), metascutellum less than 2.5 times as high as height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum ( Fig. 48 View FIGURES 44–48 ). Most closely resembles A. megatruncicolus ; however, in A. truncicolus the body is predominantly blackish brown, the head is more rounded in front view, 1.5 times as broad as long from above, 1.3–1.4 times as broad as high in front view, the ratio between the cross diameter of eye (measuring along the transfacial line) and the width of gena behind eye (measured at the same point)> 4.5, OOL 1.4 times as long as LOL, the diameter of the antennal torulus about 1.6 times as large as the distance between them ( Fig. 25 View FIGURES 25–32 ), the mesoscutellum rounded with more delicate sculpture towards the centre of scutellar disk ( Fig. 31 View FIGURES 25–32 ), scutellar foveae nearly rounded, the radial cell of the forewing 4.3–4.6 times as long as broad ( Fig. 35 View FIGURES 33–43 ) while in A. megatruncicolus , according to Tavakoli et al. (2008), the body is predominantly reddish brown, the head is less rounded, nearly trapezoid in front view, 2.0 times as broad as long from above, 1.5 times as broad as high in front view, the ratio between the cross diameter of eye (measuring along the transfacial line) and the gena width behind eye (measured at the same point) <3.5, OOL 2.8 times as long as LOL, the diameter of antennal torulus nearly 2.5 times as large as the distance between them, the mesoscutellum broader than long, with more dull rugose sculpture along sides of the mesoscutellum and more delicate on the disk center, the radial cell of the forewing only 4.0 times as long as broad.

A. truncicolus resembles A. turcicus . In A. truncicolus the lower face is coriaceous, the malar space 0.4 times as long as height of eye, coriaceous, with numerous distinct strong striae radiating from clypeus and extending half the distance to lower edge of eye ( Figs 25–27 View FIGURES 25–32 ), F2 longer than F3 ( Fig. 28 View FIGURES 25–32 ), the mesoscutum coriaceous, scutellar foveae nearly rounded, as broad as high, with shiny, smooth bottom ( Fig. 31 View FIGURES 25–32 ), the radial cell of the forewing narrower, 4.3–4.6 times as long as broad ( Fig. 35 View FIGURES 33–43 ). In A. turcicus , according to Mutun et al. (2014), the lower face is uniformly delicately coriaceous, F2=F3, the malar space 0.2 times as long as height of eye, coriaceous, without striae, the mesoscutum uniformly and entirely reticulate, scutellar foveae transversely ovate, 2.2 times as broad as high, with delicately coriaceous bottom, the radial cell of the forewing 3.4 times as long as broad.

A. truncicolus also resembles A. synophri Pujade-Villar, Tavakoli & Melika, 2015 from which it differs in having the body length around 4.0 mm, F1 longer than F2 ( Fig. 28 View FIGURES 25–32 ) and the metasomal terga without micropunctures ( Fig. 38 View FIGURES 33–43 ) while A. synophri , according to Pujade-Villar et al. (2015), is smaller in size, around 3.0 mm has F1 slightly shorter than F2, and with micropunctures on the metasomal terga.

Description of sexual generation of Andricus truncicolus ( Giraud, 1859)

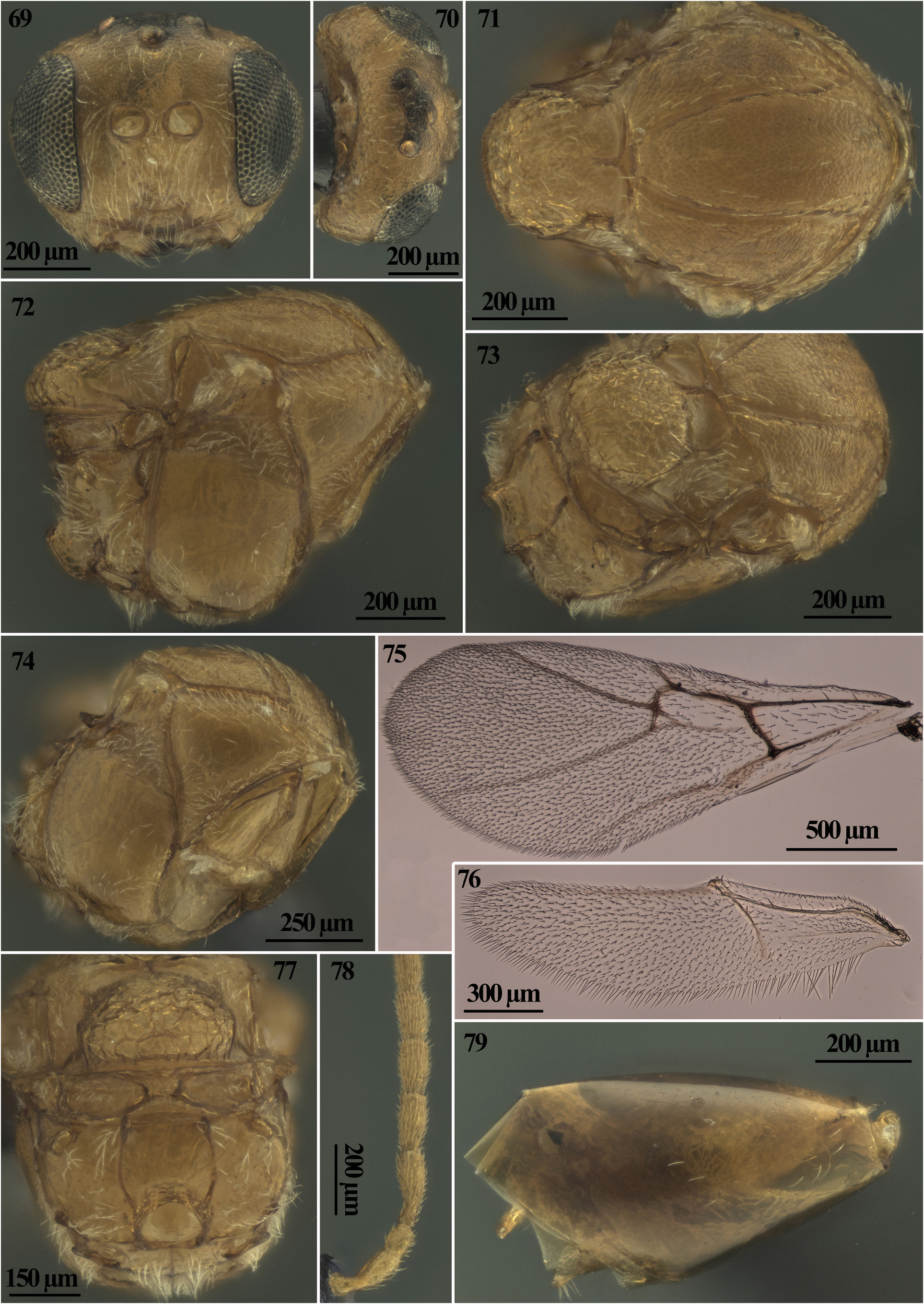

Figs 23, 24 View FIGURES 18–24 , 49–79 View FIGURES 49–57 View FIGURES 58–68 View FIGURES 69–79

Diagnosis of the sexual form

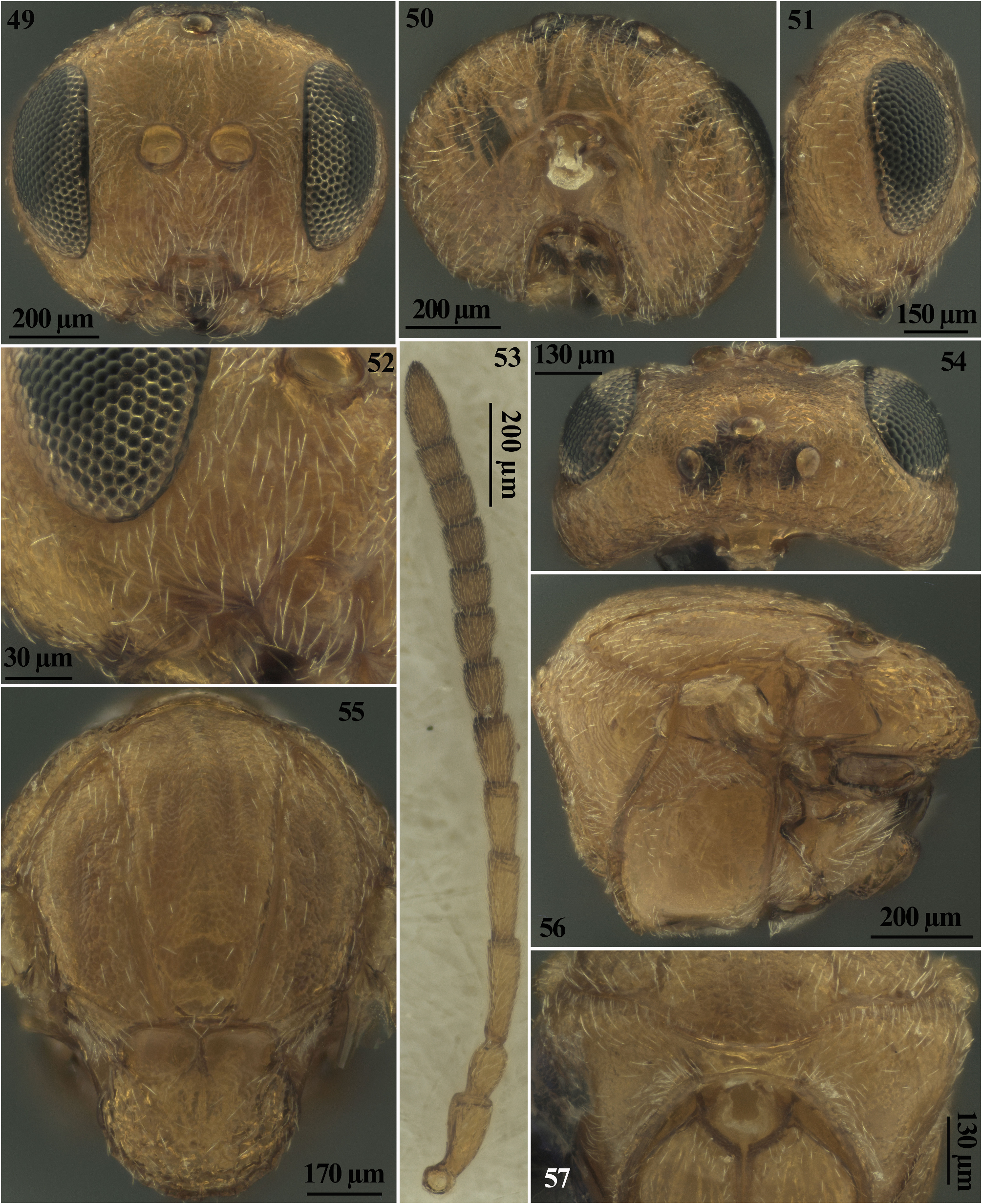

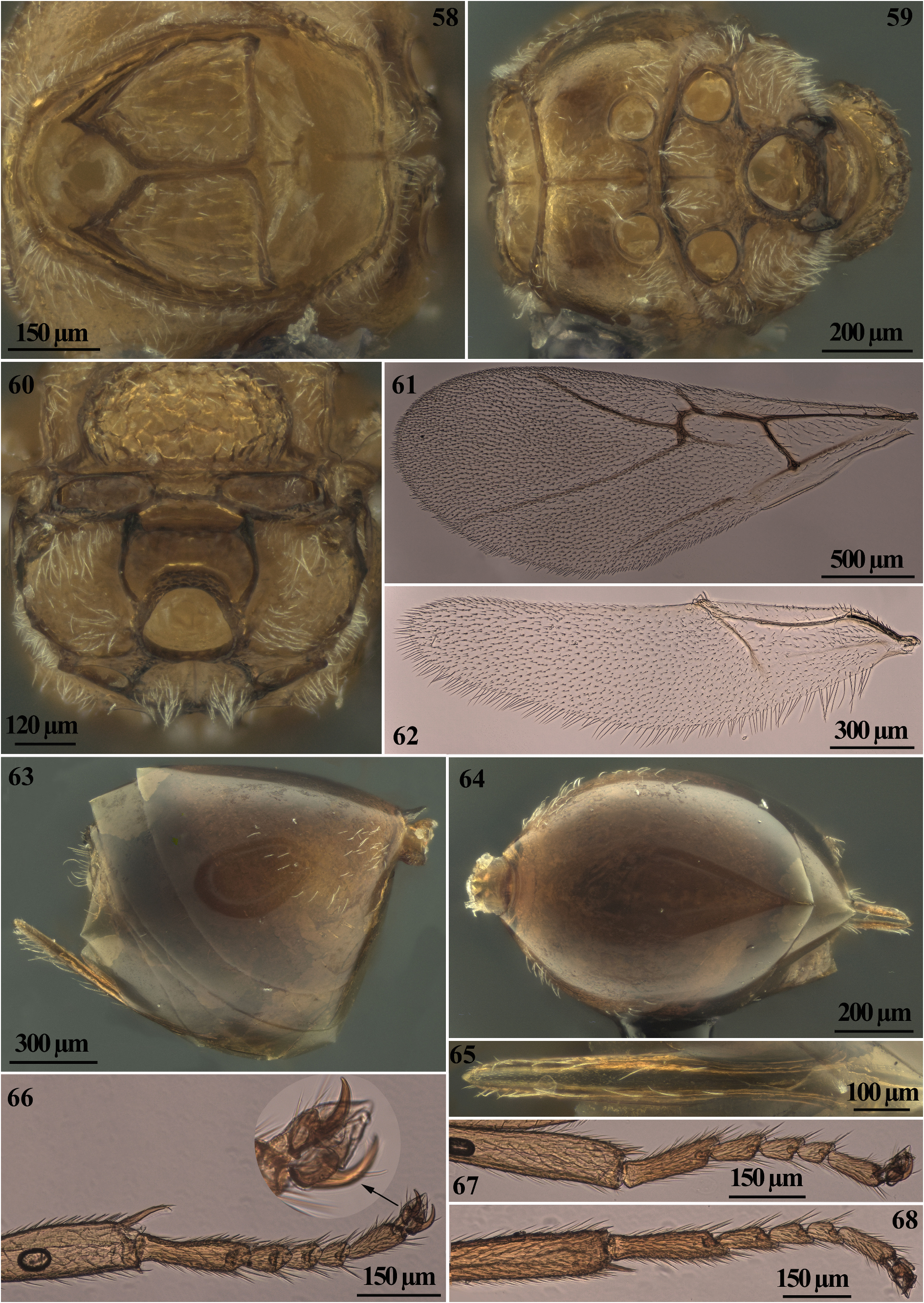

It closely resembles A. multiplicatus sexual (according to redescription given by Melika 2006); however, in sexual females of A. truncicolus , body predominantly reddish yellow, mesosoma never darker brown or black dorsally. Antennae reddish yellow slightly lighter than body; legs yellow-amber except for light brown Ts5 and dark brown tarsal claws. Lower face with striae radiating from clypeo-pleurostomal line nearly reaching eye but not present medially on the lower face and not reaching toruli ( Figs 49, 52 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Pronotum alutaceous without rugae ( Figs 56, 57 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Mesoscutum ( Fig. 55 View FIGURES 49–57 ) shallowly colliculate; as long as wide from above (width measured across base of tegulae); median mesoscutal line absent; antero-admedian line not impressed, very faintly visible in antero-dorsal view ( Fig. 57 View FIGURES 49–57 ), parapsidal lines absent. Mesoscutellum distinctly overhanging metanotum. Scutellar foveae ellipsoidal 1.4– 1.5 times broader than high ( Fig. 55 View FIGURES 49–57 ), weakly delimited posteriorly. Mesopleuron ( Figs 56 View FIGURES 49–57 , 59 View FIGURES 58–68 ), mostly smooth, glossy, with or without very indistinct striae on anterodorsal and ventral part, essentially glabrous except very sparse short white setae close to the mesocoxal foramen and on anterodorsal part; acetabular carina delimiting a narrow smooth area laterally ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 58–68 ). Metascutellum ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ) slightly narrower than height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum. Lateral propodeal carinae slightly curved outwards in the middle ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ). Radial cell of forewing 3.6–4.0 times as long as broad ( Fig. 61 View FIGURES 58–68 ); Rs+M extending to ½ distance between areolet and basal vein. Metasomal tergum 2 with sparse white setae in T2 antero-laterally ( Fig. 63 View FIGURES 58–68 ) without micropunctures, subsequent terga with band of very indistinct micropunctures.

In females of A. multiplicatus sexual, body predominantly brown to light brown, usually mesosoma and metasoma darker or even black dorsally. In some specimens scutum, scutellum, propodeum and metasoma dorsally are black. Antennae and legs brown, slightly lighter than body. Lower face with striae radiating from clypeus nearly reaching toruli. Pronotum mainly coriaceous, with some strong wrinkles along antero-lateral edge. Mesoscutum finely uniformly rugose, slightly longer than broad (width measured across the basis of tegulae). Median mesoscutal line distinct, extending to 1/3–1/4 of scutum length; parapsidal lines distinct, reaching well above the level of the base of tegulae; antero-admedian line extending to half of scutum length. Mesoscutellum slightly overhanging metanotum. Scutellar foveae nearly rounded, only slightly broader than high, posteriorly delimited by sculpture. Mesopleuron uniformly transversely striate, with dense patch of white setae postero-ventrally; acetabular carina delimiting a broad rugose area laterally. Metascutellum nearly 2.0 times as high as height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum; lateral propodeal carinae slightly curved outwards in the posterior 1/3. Radial cell of forewing 4.5–4.7; Rs+M extending to 2/3 of distance between areolet and basal vein. Metasomal tergum 2 with dense patch of white setae antero-laterally; all terga without micropunctures.

In male of A. truncicolus , F1 excavated in basal half ( Fig. 78 View FIGURES 69–79 ); with or without very indistinct striae on anterodorsal and ventral part ( Figs 72, 74 View FIGURES 69–79 ), while in males of A. multiplicatus (according to redescription given by Melika 2006) F1 almost straight or only weakly curved, sometimes also weakly excavated; mesopleuron uniformly transversely striate.

It closely resembles Andricus singularis Mayr, 1870 ; however, in females of A. truncicolus sex the body is mostly reddish yellow ( Fig. 23 View FIGURES 18–24 ), legs slightly lighter than body, the diameter of antennal torulus nearly 2.0 times as large as distance between them ( Fig. 49 View FIGURES 49–57 ), mesoscutum shallowly colliculate, mesoscutellum broader than long, reticulate-rugose around its limits, more delicate in the central part of disk, scutellar foveae subrectangular and not or very slightly delimited posteriorly with glossy, smooth bottom ( Fig. 55 View FIGURES 49–57 ), mesopleuron with or without very indistinct striae ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 49–57 ), while in females of A. singularis the body is mostly dark brown to black, legs dirty brown, coxae darker, mid legs brown, the diameter of antennal torulus at least 3.0 times as large as distance between them, mesoscutum alutaceous-reticulate, mesoscutellum slightly longer than broad, uniformly rugose, with distinct sharp rugae, scutellar foveae rounded, as broad as high, well delimited around, with coriaceous bottom, mesopleuron entirely or partially longitudinally striate, sometimes with small non-striate area posteriorly. In the male of A. truncicolus the body is mostly reddish yellow ( Fig. 24 View FIGURES 18–24 ), legs slightly lighter than body, F1 1.3 times longer than F2 ( Fig. 78 View FIGURES 69–79 ), mesopleuron with or without very indistinct striae on anterodorsal and ventral part ( Figs 72, 74 View FIGURES 69–79 ), mesoscutellum rugulose, with more delicate sculpture towards the centre of disc ( Fig. 71 View FIGURES 69–79 ) while in males of A. singularis the body mostly reddish to black, F1 only 1.2 times as long as F2, mesopleuron finely striate in anterior 2/3, remainder of surface smooth and glossy, mesoscutellum alutaceous with glossy areas.

Moreover, the sexual generation galls of A. truncicolus are indistinguishable from those of A. conificus while the inducers are easily differentiated. In sexual females of A. truncicolus body is predominantly reddish yellow, legs slightly lighter than body; frons, vertex, and occiput uniformly coriaceous. Mesopleuron with or without very indistinct striae; mesoscutellum broader than long, reticulate rugose around its limits, more delicate in the central part of disk with unemarginated posterior margin. Scutellar foveae subrectangular not or very slightly delimited posteriorly; mesoscutum shallowly colliculate. White setae on prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium few, long (about one and a half times the median diameter of the hypopygium in lateral view), curved, and slightly extending behind apex of spine. In females of A. conificus sex, body mostly dark brown to black, with yellow legs, except for proximal part of hind coxae being dark brown; frons, vertex, and occiput reticulate. Mesopleuron with very marked striae on; mesoscutellum as long as is broad, uniformly strongly areolate-rugose with distinct mainly longitudinal sharp rugae with emarginate posterior margin. Scutellar foveae subtriangular well-delimited posteriorly; mesoscutum deeply colliculate. White setae on prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium very few, short (approximately as long as the median diameter of the hypopygium in lateral view), erect, and not extending behind apex of ventral spine. In males of A. truncicolus body predominantly reddish yellow, legs slightly lighter than body. Diameter of torulus (including rims) equal to eye-torulus distance; eye-torulus distance nearly 3.0 times as large as distance between toruli. Frons and vertex coriaceous. Scutellar foveae subrectangular not or very slightly delimited posteriorly. Mesoscutellum around its limits, reticulate rugose, more delicate or coriaceous in the central part of disk, with unemarginate posterior margin. Mesoscutum shallowly colliculate; mesopleuron with or without very indistinct striae; ratio of breadth to height of metascutellum less than 1.5.

In males of A. conificus body mostly dark brown to black, with yellow legs, except for proximal part of hind coxae being dark brown. Diameter of torulus (including rims) nearly 1.6 times eye-torulus distance; eye-torulus distance nearly 1.4 times as large as distance between toruli. Frons and vertex rugose. scutellar foveae subtriangular well-delimited posteriorly. mesoscutellum around its limits, strongly reticulate rugose, more delicate or colliculate in the central part of disk, with emarginate posterior margin. Mesoscutum deeply colliculate; mesopleuron with very marked striae; ratio of breadth to height of metascutellum more than 2.0.

Description

Sexual female. Body length 1.8–2.2 mm. Body with sparse white setae, predominantly reddish yellow, antennae slightly lighter than body, excluding the distal half which are darkened; eyes black; legs yellow-amber except for light brown Ts5 and dark brown tarsal claws. Mesosoma reddish yellow, in some specimens with 2–4 darker longitudinal stripes on mesoscutum. Metasoma light brown except T2 which is dark reddish yellow dorsally and laterally for more than 3/4 of its length; wings hyaline, veins yellow-brown to brown.

Head with sparse white setae slightly more dense on lower face, nearly 1.1–1.3 times as broad as high in anterior view ( Fig. 49 View FIGURES 49–57 ), 1.9–2.0 times as broad as long in dorsal view ( Fig. 54 View FIGURES 49–57 ); frons, vertex and interocellar area uniformly coriaceous, with irregular dark spot in the ocellar area in some specimens ( Fig. 54 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Lower face alutaceous, with striae radiating from clypeo-pleurostomal line nearly reaching eye and not present medially on the lower face; malar sulcus absent ( Figs 49, 52 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Clypeus smooth, trapezoid, ventral margin projecting over mandibles, marked by prominent epistomal sulcus, and with rare setae; anterior tentorial pits and clypeo-pleurostomal line distinct and ventrally emarginated. Gena alutaceous to delicately coriaceous ( Fig. 51 View FIGURES 49–57 ), not broadened behind eye in front view, covered in sparse setae. Occiput coriaceous with few white setae; postgena alutaceous to delicately coriaceous, with sparse white setae; area around occipital foramen impressed, without or with rare setae. Postocciput around occipital foramen impressed; posterior tentorial pits distinct, elongate, deep; occipital foramen slightly higher than height of postgenal bridge, which is nearly 2.0 times shorter than length of oral foramen; gula narrowed in lower half with very few and delicate longitudinal striae in lower half; gular sulci very weakly impressed, curved outwards in the upper half ( Fig. 50 View FIGURES 49–57 ).

Malar space 0.3 times as long as height of compound eye. Transfacial distance 1.0–1.1 times as long as height of eye and 1.5–1.6 times as long as height of lower face (distance between antennal rim and tip of clypeus); diameter of torulus (including antennal rims) nearly two times the distance between them; distance between torulus and inner margin of eye nearly equal to the diameter of torulus. Ocelli elliptical in shape, elevated over dorsal margin of head; POL 1.5–1.6 times as long as OOL; OOL 2.0 times as long as diameter of lateral ocellus and 1.4–1.5 times as long as LOL. Inner margins of eyes parallel.

Antenna ( Fig. 53 View FIGURES 49–57 ) with 11 flagellomeres, longer than head+mesosoma, with short and sparse setae on all flagellomeres; pedicel longer than broad, scape + pedicel 1.5–1.6 times longer than F1, which is slightly longer than F2; subsequent flagellomeres F3–F7 gradually decreasing in length, F7–F10 nearly of the same length and as broad as long, F11 2.0–2.2 times longer than F10; placodeal sensilla visible on F4–F11.

Mesosoma 1.2–1.3 times as long as high in lateral view ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 49–57 ).

Pronotum alutaceous, with few long white setae along antero-lateral edge, more densely along anterior rim of pronotum and in the posteroventral corner of pronotum, rare in other parts; anterior rim of pronotum narrow, emarginate; transverse pronotal sulcus present, shallow, striate; posterolateral pronotal area, latero-median and median area of pronotum alutaceous without rugae ( Figs 56, 57 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Propleuron alutaceous, smooth, with sparse short setae, ( Fig. 58 View FIGURES 58–68 ). Mesoscutum ( Fig. 55 View FIGURES 49–57 ) shallowly colliculate, with sparse white setae along its lateral margin and along notauli; as long as wide from above (width measured across base of tegulae); notauli complete, deeply impressed for full length smooth, glossy; median mesoscutal line absent; antero-admedian line not impressed, very faintly visible in antero-dorsal view ( Fig. 57 View FIGURES 49–57 ), parapsidal lines absent; parascutal carina narrow, anteriorly reaching notauli, mesoscutal suprahumeral sulcus not sculptured.

Transscutal articulation deep, distinct. Mesoscutellum nearly as long as broad from dorsal view, 1.8–1.9 times shorter than mesoscutum, rounded, not elongated, marginated, rugulose, with more delicate sculpture towards the centre of disc, with rare long white setae; distinctly overhanging metanotum. Scutellar foveae ellipsoidal 1.4–1.5 times broader than high ( Fig. 55 View FIGURES 49–57 ), weakly delimited posteriorly and separated by distinct, narrow, central carina, deep with smooth and glossy bottom.

Mesopleural triangle uniformly coriaceous, densely pubescent ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 49–57 ).

Mesopleuron ( Figs 56 View FIGURES 49–57 , 59 View FIGURES 58–68 ), mostly smooth, glossy, with or without very indistinct striae on anterodorsal and ventral part, speculum smooth and glossy; essentially glabrous except very sparse short white setae close to the mesocoxal foramen and on anterodorsal part.

Pleurosternum smooth, glossy, with very faint wrinkles between mesocoxal foramina and mesofurcal pit; metasubpleuron smooth, glossy with sparse long white setae; acetabular carina delimiting a narrow smooth area laterally ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 58–68 ).

Metapleural sulcus reaching mesopleuron in the upper 1/3 of its height ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 49–57 ); areas delimited by the inferior and superior parts of metapleural sulcus coriaceous, with dense white setae; preaxilla smooth and glossy; dorsal axillar area alutaceous with dense white setae; lateral axillar area smooth and glossy; axillar carina distinct and narrow; axillula subtriangular smooth, glossy, with dense white setae; subaxillular bar triangular, narrow, smooth and glossy, at posterior end shorter than height of metanotal trough and rugose ( Fig. 56 View FIGURES 49–57 ). Propodeal spiracle elevated, ovate, carina extending from spiracle distinctly raised; pit above spiracle deep, smooth, glossy; area between metapleural sulcus and spiracle glossy, with some punctures and rare setae.

Metascutellum ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ) trapezoidal, broad, more than 2.0 times as broad as high, smooth or very delicately sculptured, nearly straight inferiorly, slightly narrower than height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum, which is smooth; metanotal trough smooth, glossy, with rare white setae. Lateral propodeal carinae distinct and percurrent, slightly curved outwards in the middle ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ), strong and uniformly thick, which end dorsally in a thick protruding small process ( Figs 59, 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ), central propodeal area glabrous, smooth, glossy, without median propodeal vertical carina and without setae; central propodeal area short, more than 2.5 times broader than long, with its height equal to or slightly shorter than height of metascutellum+height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum; lateral propodeal area alutaceous with some very delicate rugae and with relatively dense white setae; nucha short, acinose dorsally and with irregular wrinkles laterally ( Fig. 60 View FIGURES 58–68 ). Forewing ( Fig. 61 View FIGURES 58–68 ) pubescent, hyaline, 1.3–1.4 times as long as body, with distinct brown veins and long marginal cilia; radial cell open, 3.6–4.0 times as long as broad; R1 and Rs nearly reaching wing margin, Rs slightly extending along wing margin; 2r curved; areolet distinct, triangular; 2r-m not extending along M vein; Rs+M weakly marked and extending to ½ distance between areolet and basal vein.

Hindwing ( Fig. 62 View FIGURES 58–68 ), pubescent, hyaline, long-ciliate, very weakly clouded around veins without infuscate stripe on the anterior margin. All tarsal segments longer than broad, Ts1 the longest one; tarsal claws with basal lobe; fore tarsomere I (Ts1) to V (Ts5) length ratio as 1.0:0.4:0.3:0.2:0.5; tibial spur slightly curved inward, bifid at apex, nearly 0.5 times as long as basitarsus of foreleg ( Fig. 66 View FIGURES 58–68 ). Metasoma as long as mesosoma, about 0.8 times as long as length of head + mesosoma. Metasoma nearly as long as high in lateral view or very slightly longer than high, smooth, glossy, with sparse white setae in T2 antero-laterally ( Fig. 63 View FIGURES 58–68 ); metasomal tergum 2 without micropunctures, subsequent terga with band of very indistinct micropunctures; prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium 5.5–6.0 times as long as broad in ventral view, with few, long white setae (about 1.5 times the median diameter of the hypopygium in lateral view), curved, and slightly extending behind apex of spine but never forming a tuft ( Figs 63–65 View FIGURES 58–68 ).

Male. Body length 1.9–2.5 mm. Similar to female, but POL 2.0 times as long as OOL; OOL 1.6 times as long as diameter of lateral ocellus and nearly equal to LOL ( Fig. 70 View FIGURES 69–79 ). Antenna with 12 flagellomeres, F1 distally slightly broadened, excavated in basal half ( Fig. 78 View FIGURES 69–79 ); scape + pedicel 1.2–1.3 times longer than F1; placodeal sensilla visible on F1–F12. Mesoscutum ( Fig. 71 View FIGURES 69–79 ) as long as wide from above (width measured across base of tegulae). Mesopleuron with or without very indistinct striae on anterodorsal and ventral part ( Figs 72, 74 View FIGURES 69–79 ). Pleurosternum without wrinkles between mesocoxal foramina and mesofurcal pit. Metascutellum ( Fig. 77 View FIGURES 69–79 ) narrow, nearly as high as broad, curved inferiorly, slightly broader than height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum. Lateral propodeal carinae distinct and percurrent, very slightly curved outwards in posterior 1/3 ( Figs 73, 77 View FIGURES 69–79 ); central propodeal area longer, less than 1.5 times broader than long; with its height from 1.4 to 1.5 times as height as metascutellum+height of ventral impressed rim of metanotum; lateral propodeal area with sparse white setae. Forewing similar to female but Rs+M nearly reaching basal vein in the lower half ( Fig.75 View FIGURES 69–79 ); hindwing similar to female but with narrow infuscate stripe on the anterior margin, starting from hamuli and extending along the margin for more than 3/4 of its length ( Fig. 76 View FIGURES 69–79 ).

Biology and host plant. Species shows a regular heteroecic life cycle (i.e. obligate alternation between two generations, sexual and asexual, form galls on two different oak species). Results of the rearing assay and material obtained from field sampled galls demonstrated that A. truncicolus asexual generation develops on oaks of the section Quercus ( Q. petraea , Q. pubescens ) while the sexual generation develops on oaks of the section Cerris ( Q. cerris , Q. suber ). Sexual generation galls begin to develop in the second half of April, mature in May and the adults emerge from the mid- to late June to July. The emerged sexual adults copulate and lay eggs preferably on adventitious buds on thicker stems and branches, and the asexual galls begin to develop in the spring of the following year. We hypothesise that from the egg laying to the development of the galls (about 10 months) a diapause occurs at the egg stage or during latent growth of the gall, when it is not yet visible. The gall grows and becomes visible in May, matures in summer when the tissues are completely lignified. Metamorphosis to the pupal stage is observed in October ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 1–6 ), and the adult emerges in March of the following year. The life cycle of A. truncicolus is completed in two years (three, when the asexual female emerges in the second year). Moreover, the emergence of only male or female adults from sexual galls induced by each of the two asexual females used in the experiment (in which we obtained 3 galls from which 8, 48 and 30 females emerged, respectively, and two galls from which 6 and 20 males emerged, respectively), and the emergence of only males from most of the sexual galls collected in the field (see “Additional material examined for morphological diagnosis.”) suggests that two different types of asexually reproducing females, androphores (producing haploid male eggs by meiosis) and gynephores (producing diploid female eggs), occur in A. truncicolus , following a pattern already known in the Cynipini . The occurrence of asexual androphore and gynephore females is known for several members of the genera Andricus , Cynips , Neuroterus and for Plagiotrochus amenti Kieffer, 1901 ( Folliot 1964; Askew 1984; Stone et al. 2002; Garbin et al. (2008) and for A. conificus (unpublished data). This reproductive strategy appears to reduce the benefits of strict parthenogenesis in asexual females. Furthermore, the occurrence in the same biotope of both section Cerris oaks and section Quercus oaks is needed to support the complete heteroecic cycle of the insect. Despite this, A. truncicolus is widespread in the Western Palaearctic region, and can be found in both natural and sub-urban areas where the host plants are present, showing good resilience even in fragmented natural ecosystems.

Distribution. Widely distributed in the Western Palaearctic region: Austria, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Hungary, Ukraine (Transcarpathian Region only), Romania, Albania, Poland, Greece, ( Melika 2006), Serbia ( Marković 2022) Croatia ( Kwast 2012), Turkey ( Katılmış & Kıyak 2008).

Concerning Italy, it is known from the northern and southern regions, including Sicily ( De Stefani 1901; Massa et al. 2021).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |