Akodon spegazzinii Thomas, 1897

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.293461 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6196155 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E91F87ED-FF98-FFB9-D9DA-8C02FD28FAC9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Akodon spegazzinii Thomas, 1897 |

| status |

|

Akodon spegazzinii Thomas, 1897

Akodon spegazzinii Thomas, 1897 . Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 6(20): 216.

Akodon tucumanensis J. A. Allen, 1901 . Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 14: 410. Akodon alterus Thomas, 1919 . Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 9(3): 496.

Akodon leucolimnaeus Cabrera, 1926 . Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 30:320.

Holotype: B.M. 97.5.5.14.

Type locality: Lower Cachi ( Thomas 1897). Probably Thomas referred to the lower course of the Río Cachi which passes through the town of Cachi, close to the junction with the Río Calchaquí. The town is situated in the Deparment of Cachi, in central Salta Province (25º 07`11.93``S, 66º 09`47.00``W, 2341 m).

Description: Because of the terse description of the species ( Thomas 1897) and the paucity of specimens available to later workers ( Myers et al. 1990; Díaz 1999), here we offer a more detailed description of A. spegazzinii based on topotypic specimens but including also material coming from the known range of the species.

General coloration remarkably variable, with individuals ochraceous brown, ruddy brown, fulvous brown, and buffy brown, and darker or paler depending on individuals and populations. Dorsal coloration uniform from head to rump and with more or less spattered black or dark brown hairs. The yellow eye ring are always present but its development is variable. Ears of same color as dorsum. Flanks with the same coloration as dorsum but some clearer. The venter is buffy, ruddy gray or ochraceous gray and contrast lightly with the dorsum. The chin is covered by a few isolated white hairs that do not form a conspicuous patch. Inguinal region of some individuals with a more intensive hue. Both fore and hind feet covered with bicolored hairs and whitish, buffy or greyish in appearance. Claws covered with tufts of hairs greyish brown at the base and tipped white. Tail conspicuously bicolored, dorsally brown or blackish brown and ventrally whitish or buffy, more or less furred depending on population.

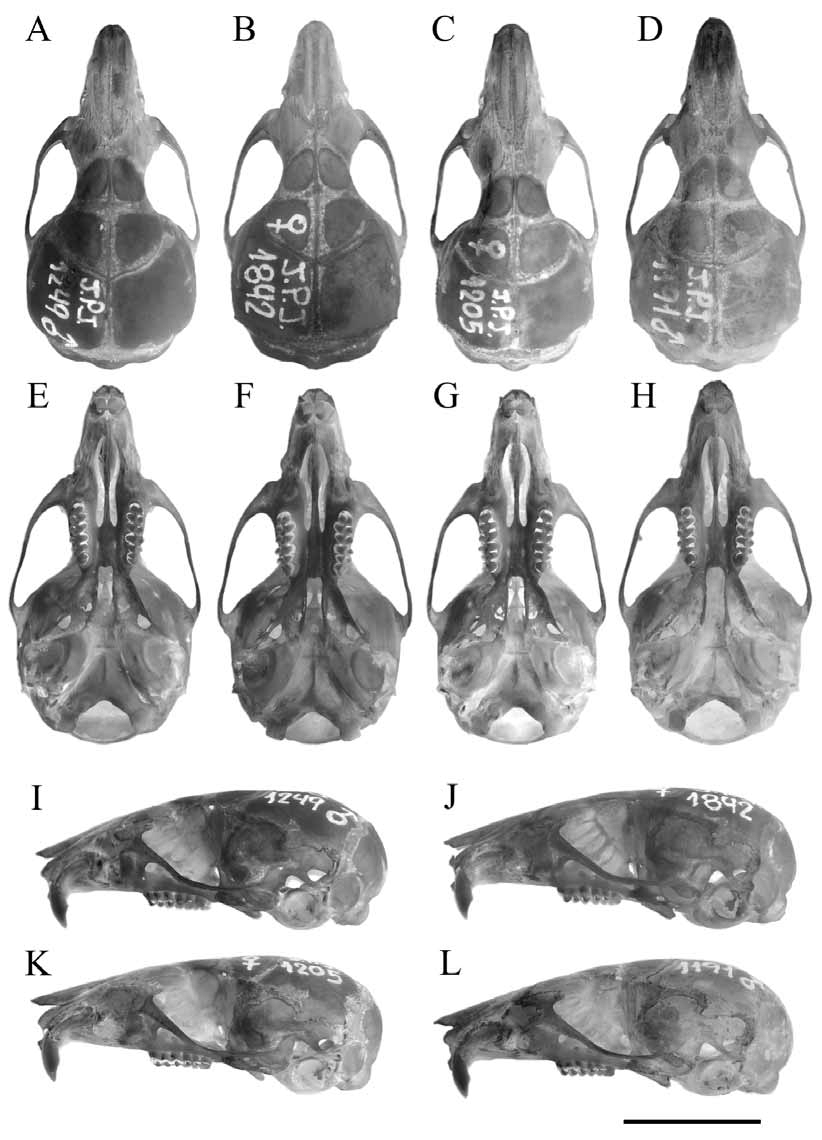

Skull of intermediate size for the boliviensis group and characterized by a well-developed rostrum, relatively narrow zygomatic notches, and lightly swollen frontal sinuses. Interorbital region hourglass shaped, with rounded or slightly squared margins and without overhanging borders. Zygomatic arches not specially flared. The braincase is relatively inflated, but some variation exists among individuals. Temporal and lambdoid crests relatively well developed, mainly in old individuals. Dorsal profile of the cranium relatively arched, especially in young specimens. Zygomatic plate breadth generally intermediate in size but highly variable among individuals. The anterior margin is straight or slightly concave with its dorsal root gently sloping backward. Hamular process generally slender and expanded in its distal end. Posterior ascending process of alisphenoid reaches or surpasses the squamoso-alisphenoid groove. Postglenoid foramen and subsquamosal fenestra are developed, and the ratio between them is highly variable. Incisive foramina relatively long, extended in some specimens to the anterior border of hypocone of M1. Mesopterygoid fossa of intermediate breadth for the group, with the anterior margin slightly rounded or squared and with the lateral borders straight and slightly divergent backward. The medial process of posterior palate can be present but never is well developed. Posteropalatal pits generally tiny and situated at the same level or slightly backward with respect to the anterior margin of mesopterygoid fossa. Parapterygoid fossae of the same breadth or slightly broader than mesopterygoid fossa, relatively shallow, with lateral margins straight or slightly convex, diverging backwards. Tympanic bullae not especially developed with Eustachian tubes generally broad and short. Mandibular ramus delicate. Anterior end of maseteric crest situated just behind the level of the anterior border of M1. The development and position of the capsular projection is variable: in general, it is conspicuous and situated slightly behind the posterior border of the coronoid process. This process is delicate and extends just above the condyloid process. The condyle extends behind the posterior margin of angular process.

Upper incisors orthodont, with yellowish orange enamel. Molars with crested crown. M1 with well developed procingulum and anteromedian flexus. The anteroloph is conspicuous, the mesoloph is short and the enteroloph is very small (sometimes missing). A small parastyle can be observed in some specimens. The posteroflexus is poorly developed. M2 with a remnant of anteroloph, which determines a relatively well-developed paraflexus. A weak mesoloph and a very shallow protoflexus and posteroflexus also characterize this molar. M3 with paraflexus and metaflexus clearly visible in most of the examined individuals (excepting very old individuals), sometimes as enamel islands. This molar is not “8” shape because the hypoflexus is vestigial and disappears at a very young age. The m1 shows a conspicuous procingulum, well-developed anteromedian flexid and anterolabial cingulum, a tiny ectostylid, and a vestigial mesolophid. The m2 shows a very shallow protoflexid; a tiny ectolophid and a vestigial mesolophid are observable in a few specimens. The m3 presents a remnant of protoflexid, a mesoflexid and a transverse and conspicuous hypoflexid, making it “S” shaped. This molar has no trace of posteroflexid.

Akodon spegazzinii has 13-14 thoracic ribs; the vertebral column includes 13-14 thoracic, 7-8 lumbar, and 23-26 caudal vertebrae (n = 19).

Karyotype: 2n = 40, FN = 40, based on four specimens from Catamarca and one from Tucumán ( Barquez et al. 1980; Myers et al. 1990).

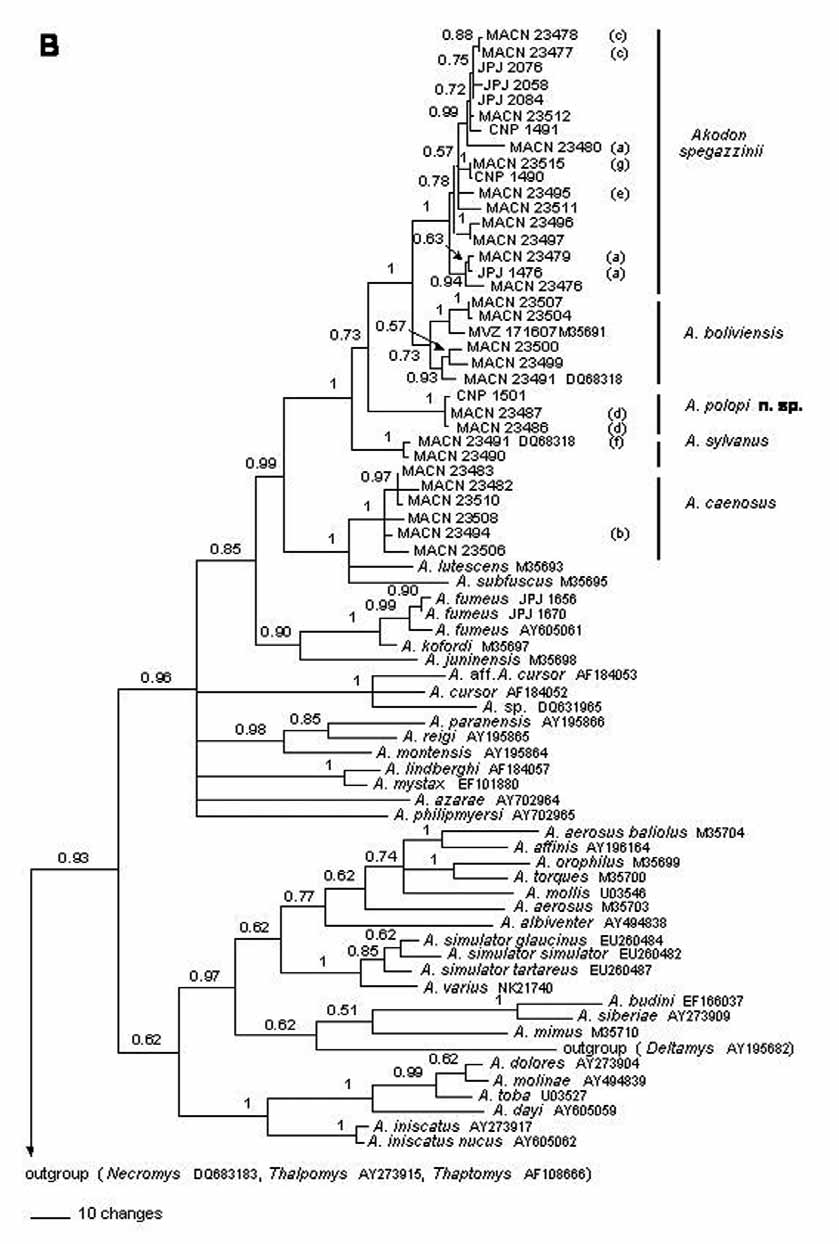

Variation: There is considerable variation in external characters among the different populations of A. spegazzinii . Most of these differences probably reflect the different environments from where they were trapped. Populations from humid and low altitude areas are darker, with predominance of black guard hairs. This condition is extreme in populations living in Yungas forest. On the other hand, those populations from open and semiarid environments, such as the Monte desert (e.g. Cachi, type locality of A. spegazzinii ) and Puna, are remarkably paler. Moreover, specimens from high altitude localities have fur, ears and tails more densely covered and with longer hairs. Variation within populations includes different color patterns, with ruddy, drabby and dark brown animals. These variations were observable even in mice trapped in the same traplines, in some cases related to reproductive condition or the age of individuals. For example, lactating females were particularly reddish in hue and young individuals darker. Morphometric differences are also conspicuous, even in individuals of the same age class. Some qualitative characters also show some variability. The zygomatic plate is highly variable, with both straight or concave anterior borders more or less sloping backwards. The zygomatic notches can be more or less narrow and shallow. The mesopterygoid fossa can be more or less broad and its anterior border rounded or squared. Our genetic sample includes 17 specimens of A. spegazzinii collected at 10 localities form Catamarca, Salta, and Tucuman provinces. This sample has high haplotypic diversity with 16 haplotypes recovered. However, all are similar as average pairwise comparison among them is 1.2%, and geographic structure is nonexistent.

Comparisons: For comparisons between A. spegazzinii and A. boliviensis or A. caenosus please see those accounts. Below we compare it with the remaining species of Akodon present in Yungas of Northwestern Argentina.

Jayat et al. (2007a) made detailed comparisons between A. spegazzinii and A. sylvanus . The most relevant differences included general size, with A. sylvanus slightly larger for all the morphometric characters analyzed ( Tables 1 View TABLE 1 and 2 View TABLE 2 ). The PCA ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ) shows some overlap for this species but the DA was very efficient, with only four of 139 individuals not reciprocally well classified. Akodon sylvanus presents also relatively less developed zygomatic notches, more inflated frontal sinuses, broader mesopterygoid fossa, broader and deeper paraterygoid fossa, more developed foramen oval, and conspicuously larger foramen magnum. The general coloration of A. sylvanus is included in the observed variation for the different populations of A. spegazzinii . Notwithstanding, the latter has a more conspicuous eye ring and white spot on the chin. The average percentage of genetic divergence between these species is 4.9% ( Table 12 View TABLE 12 ).

Akodon budini is substantially larger and shows very distinguishable craniodental characteristics. It has a very broad braincase and mesopterygoid fossa, elongated rostrum and relatively narrow and shallow zygomatic notches. The mandible is also distinguishable by the short masseteric crest and lightly developed capsular projection. Moreover, the conspicuous hypsodont molars of A. budini uniquely characterize this species.

Akodon simulator and A. spegazzinii are sympatric in parts of their ranges; however, these species are easily differentiable by the larger size of A. simulator and, more importantly, several characteristics of the skin. For example, A. simulator has a more greyish general coloration, more contrast between dorsum and venter, and presents a conspicuous white spot on chin and throat. The skull of A. simulator is more robust, with more divergent and squared interorbital region and broader mesopteryogoid fossa. Furthermore, this species has more proodont incisors.

The differences between A. spegazzinii and the new species are considered in detail below.

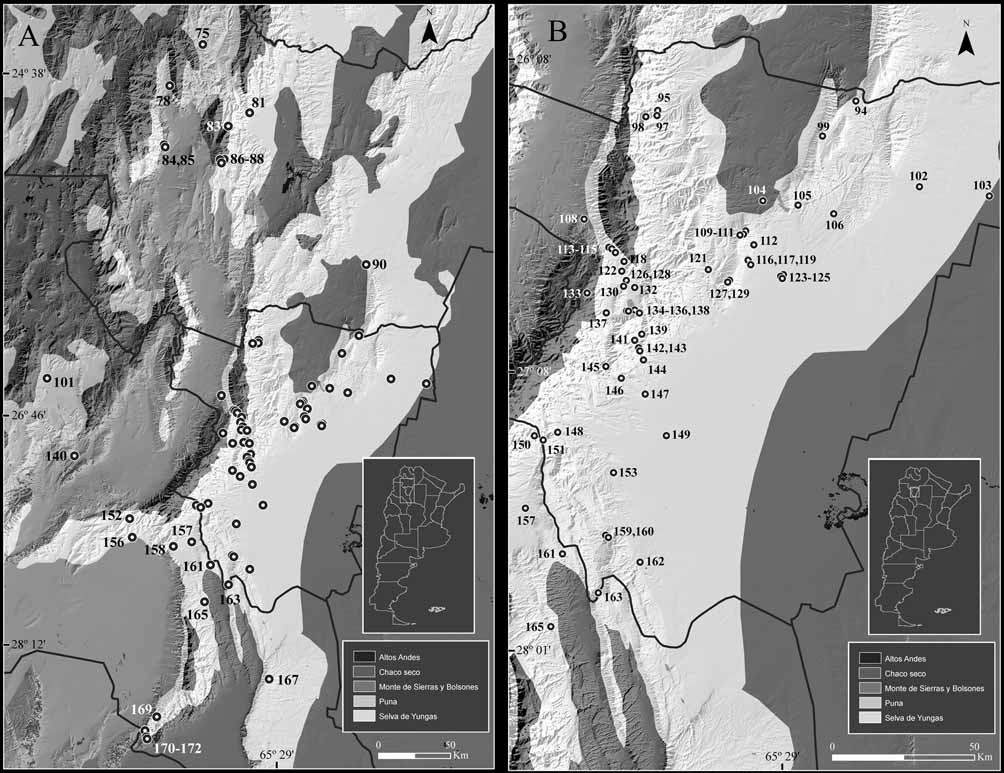

Distribution: A. spegazzinii occurs in southern and central areas of northwestern Argentina, from 24º 27’ S in central Salta to 28º 47’ S in southern Catamarca, from 400 to about 3500 m. A single specimen (CNP 1897) is known from southern Mendoza province (Laguna LLancanelo, 1335 m, Malargüe Department, 35º 45’ S, 69º 08’ W); this locality, the first reported for Mendoza province, extends the known distribution of A. spegazzinii 850 km to the south. Records from La Rioja province ( Thomas 1920b as A. alterus ), corresponding to specimens not examined by us, need confirmation ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ).

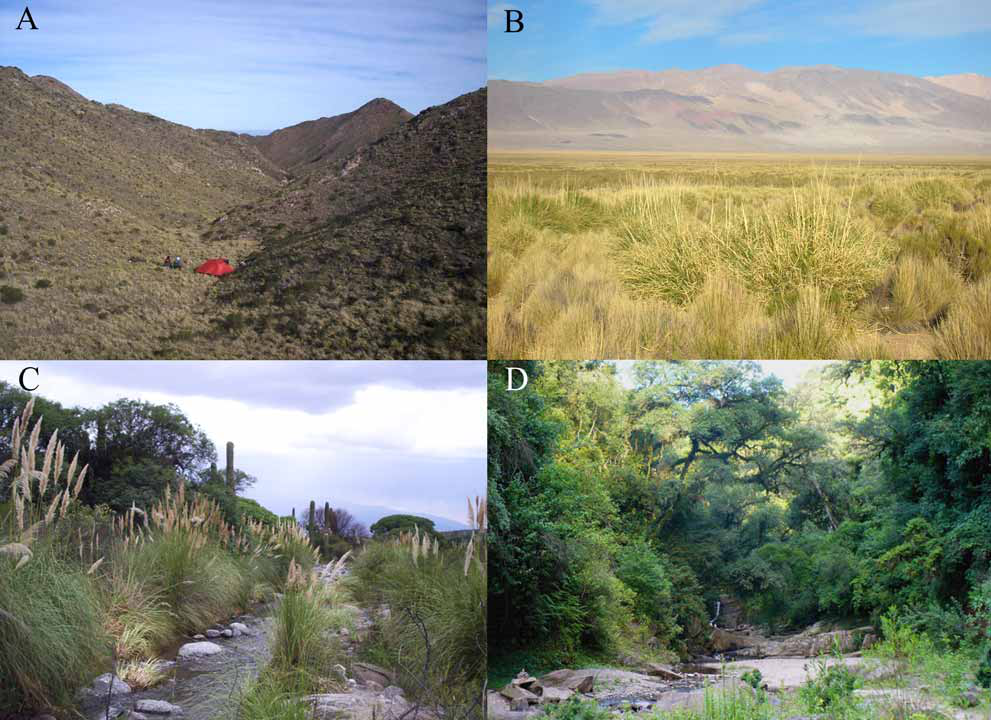

Habitat: A. spegazzinii occurs in all altitudinal belts of the Yungas forest (even ecotonal areas with lowland thorn woodlands of Chaco), Monte de Sierras y Bolsones, Puna and Altos Andes. Thus, the species inhabits forests, woodlands and grasslands. In dry areas, such as the Monte desert and Puna, it is only found in grassy zones along streams and rivers. Akodon spegazzinii is especially abundant in cloud grasslands in the upper altitudinal belts of Yungas, where it constitutes the dominant sigmodontine species ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ).

Natural History: Reproduction appears to occur yearlong, with a clear peak between November and April. Most of the individuals were molting in fall and winter (April to August). As it can be expected from the general ubiquity of the species, Akodon spegazzinii coexists with a number of sigmodontine species in the region of interest. In high altitudinal localities, above 3000 m, it has been registered alongside Calomys lepidus (Thomas) , Eligmodontia sp., Phyllotis xanthopygus , Reithrodon auritus (G. Fischer) and Neotomys ebriosus Thomas. In cloud grasslands it was caught with Necromys lactens , N. lasiurus and Phyllotis osilae . In forested areas of Yungas A. spegazzinii coexists with Abrothrix illutea , Oligoryzomys sp., Oxymycterus paramensis , O. wayku and Phyllotis anitae . In ecotonal environments of Yungas and Chaco, A. spegazzinii was caugth with Calomys fecundus Thomas , Graomys centralis and Necromys sp. Other species broadly distributted in the region, such as Akodon caenosus , Akodon simulator , Oligoryzomys cf. O. flavescens , Calomys musculinus and Andinomys edax , have also been registered in sympatry with A. spegazzinii .

Comments: Myers et al. (1990) viewed spegazzinii as a valid species and considered tucumanensis (type locality Tucumán, 450 m) as a subspecies. Moreover, Akodon alterus (from Otro Cerro, 3000 m) was considered “properly allied” to these forms. Blaustein et al. (1992) studied the status of A. alterus and A. tucumanensis and found weak morphologic and morphometric differences and identical cytogenetic characteristics in the studied populations. Notwithstanding, Mares et al. (1997) listed alterus and tucumanensis as valid species mainly based on their different ecological associations (see also Capllonch et al. 1997; Díaz et al. 1997; Díaz 1999). In the last ten years the treatment of alterus continued to be confused, alternatively considered as a valid species ( Díaz 1999; Díaz & Barquez 2007), as a subspecies of A. spegazzinii ( Díaz et al. 2000) or simply as a synonym of this last form ( Musser & Carleton 2005; Pardiñas et al. 2006). On the other hand, A. tucumanensis has been recently considered as a synonym of A. spegazzinii ( Musser & Carleton 2005) , as a subspecies of this last form ( Pardiñas et al. 2006) or as a valid species ( Díaz & Barquez 2007). Cabrera (1926) described A. leucolimnaeus based on two specimens of Laguna Blanca and one from Salar de Antofalla, Catamarca Province. Gyldenstolpe (1932) suggested that this form be included in the genus Necromys Ameghino. For many years this nominal form was considered as a synonym of Necromys lactens Thomas ( Cabrera 1961; Reig 1987; Musser & Carleton 1993; Mares et al. 1997) but Galliari et al. (1996) regarded it a valid species, allied to the A. boliviensis group. This view was maintained by Musser & Carleton (2005) and Pardiñas et al. (2006) but its status was considered provisional.

Here we offer the first detailed description for A. spegazzinii (see above). We formally tested the taxonomic status of A. alterus and A. leucolimnaeus and established their conspecificity with respect to A. spegazzinii . Moreover, we corroborated the conspecificity of tucumanesis and A. spegazzinii , as suggested by Myers et al. (1990). No clear or constant morphologic differences in skull characters among the specimens coming from Cachi, Laguna Blanca, vicinities of Otro Cerro, and Yungas forest in Tucumán were found ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ). Moreover, haplotypes recovered from specimens collected near the type locality of alterus , and assignable to this form, and at the type localities of leucolimnaeus and tucumanensis form part of the spegazzinii clade ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Therefore, the combination of genealogical, genetic ( Table 12 View TABLE 12 ), morphologic, and morphometric ( Tables 5- 8 View TABLE 5 View TABLE 6 View TABLE 7 View TABLE 8 ) evidence prompt us to suggest that A. alterus , A. leucolimnaeus , and A. tucumanensis are conspecific with A. spegazzinii . We submit that the lack of large samples, coupled with the geographic and ecotypic variation in pelage described above, misinformed the original authorities of these nominal forms. Specimens from Tucumán (type locality of tucumanensis ) have very dark tones, almost black in some exemplars, which is typical of humid cloud forest dwellers. On the contrary, specimens from Laguna Blanca, in puna environments, have very clear tones, with buffy brown coloration. Individuals coming from Cachi and Otro Cerro are intermediate in coloration although they also differ among them. Cachi presents the typical environmental features of Monte de Sierras y Bolsones, with arid to semi-arid conditions, while Otro Cerro is dominated by relatively humid grasslands communities that are characteristic of the upper belt of Yungas in transition with high Andean environments ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.