Trachodon mirabilis

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.1064078 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6295659 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E8728790-2E71-CC2F-164D-FB15FE79FE8E |

|

treatment provided by |

Jeremy |

|

scientific name |

Trachodon mirabilis |

| status |

|

With comparatively few exceptions, the living reptiles, whether turtle, saurian, serpent, or batrachian, are carnivorous in habit, and so far as we have been able to learn, such also appears generally to have been the case with the extinct forms of the same class, if we may judge from the anatomical structure of their remains.

In all the living forms of reptile life, when they are in possession of teeth, these organs are observed to be constructed for the penetration and cutting of food, whatever the nature of the latter may be; and in no known instance are they adapted to the crushing or mastication of substances. Even in the family of Iguanians, in which we find genera, such as the Iguana * of South America and the Amblyrhynchus of the Galapagos Islands, using exclusively vegetable food, the teeth with their trenchant, jagged crowns, together form an instrument adapted to cutting like a saw, rather than one intended to bruise substances.

In the same category indicated in the preceding paragraph, it had been ascertained that all extinct reptiles belonged, until the discovery in the Wealden Deposit of England, by Dr. Mantell, of the great Iguanodon . It was therefore not at all surprising when the illustrious Cuvier first observed a tooth of the latter, that he pronounced it to be the incisor of a Rhinoceros , more especially as the specimen, which was in a much worn condition, really bore a strong resemblance to the corresponding tooth it was supposed to be. Nor did the determination at the time excite any degree of wonder, though it was a matter of much surprise that remains of the Rhinoceros should have been found in a formation so ancient as the Wealden.

Dr. Mantell afterwards, having sent a number of teeth of the Iguanodon for the examination of Cuvier; the latter was led to remark,—“ It is perhaps not impossible that they may belong to a saurian, but to one more extraordinary than any of which we possess knowledge. The character which renders them unique, is the wearing away of the crown transversely, as in the herbivorous quadrupeds.”

Subsequent researches of Dr. Mantell led to the conclusion that the Iguanodon was a huge herbivorous saurian, which masticated its food in the manner of the existing pachyderm mammals.

Among the most interesting palaeontological discoveries of Dr. Hayden in Western America, are several fossil specimens from the Judith River, which prove the former existence of a large herbivorous lizard, nearly allied to the great extinct Iguanodon of Europe.

The specimens, consisting of the unworn crown of a tooth, and portions of several muchworn teeth, at the time they were sent to the author for examination, were noticed in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of this city, as characteristic of a new genus of extinct herbivorous saurians, with the name of trachodon mirabilis . Subsequently a large collection of remarkably well preserved remains of another huge saurian, closely allied to Trachodon and Iguanodon , were obtained by our fellow member, W. Parker Foulke, Esq., from the green sand clay, in the neighbourhood of Haddonfield, New Jersey, not far distant from this city. The collection was presented by Mr. Foulke to the Academy of Natural Sciences, and was the subject of a short communication, in which the animal was characterized with the name of Hadrosaurus Foulkii.

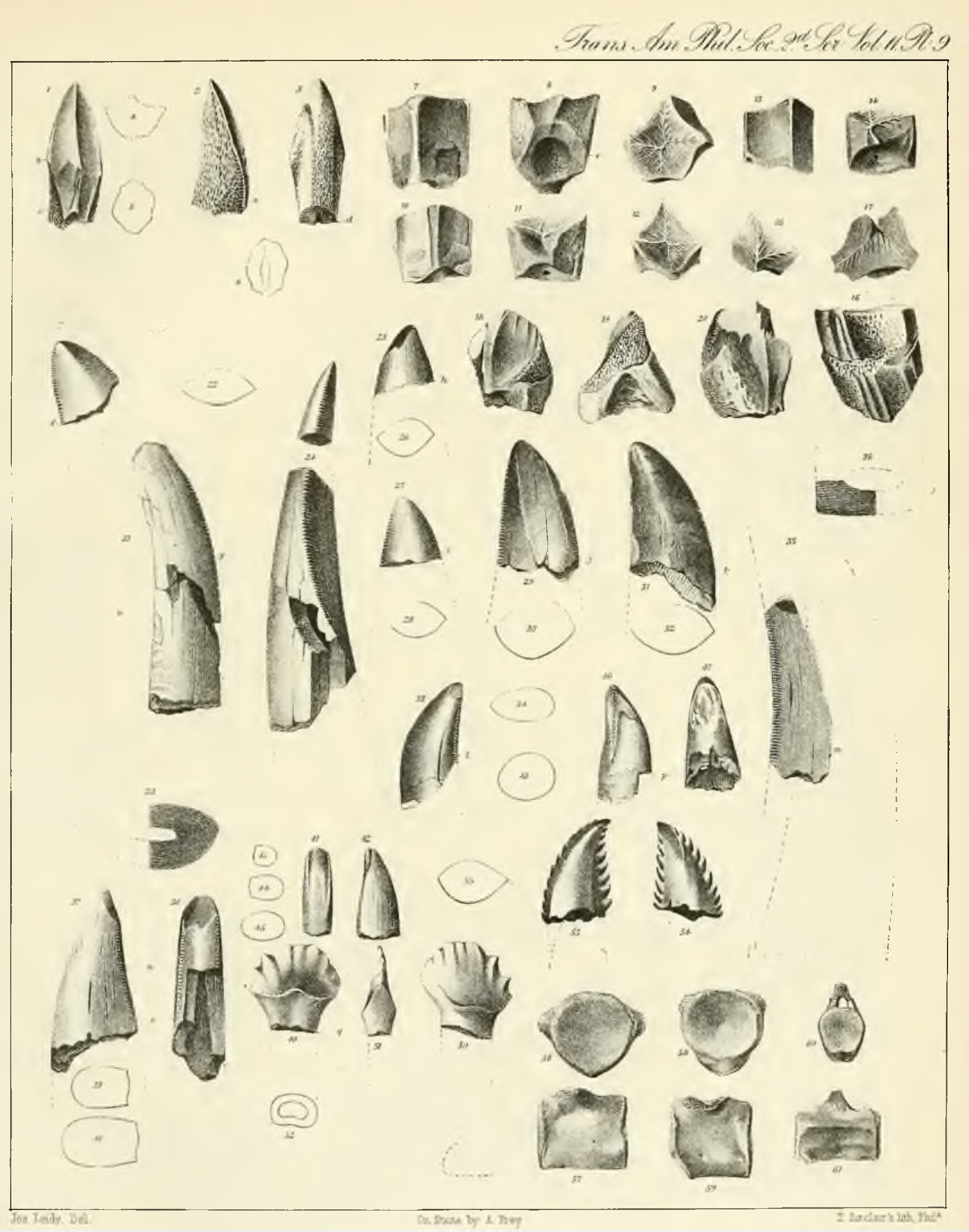

Of the specimens of teeth referred to Trachodon , the unworn crown is the most important. It is represented in plate 9, figures 1—3 View Figure , and is conical in form and slightly curved in its length. An examination of more perfect teeth of Hadrosaurus has led me to consider the specimen as having belonged to the lower jaw. Its inner face, ( fig. 1 View Figure ,) is alone invested with enamel, is lozenge-shaped in outline, and is divided by a prominent median carina or ridge. The surfaces between the latter and the lateral borders of the crown are slightly depressed, smooth and shining.

The upper borders of the lozenge-like enamelled surface are the longer, but are neither serrated nor tuberculated, though they are slightly rugose towards the outer aspect of the tooth. The apex of the latter as formed by the enamelled surface is rounded, the lateral angles are obtuse, and the inferior angle is notched.

The portion of the tooth exterior to the enamelled surface is subtrihedral above and becomes pentahedral below, ( figs. 2, 3 View Figure ,). The lateral or innermost divisions of the pentahedral portion of the crown, apparently exhibit the impress of the summits of laterally succeeding teeth, ( fig. 2, a View Figure ,) and the remaining surfaces of the exterior of the tooth are roughened with granular tubercles.

The broken base of the specimen is irregularly hexahedral in outline, and presents at its middle the open pulp cavity in the form of an ellipsoidal figure, with the long diameter directed from without inwardly. The walls of the cavity are from one to one and a half lines thick, and appear quite roughened on their interior surface.

A transverse section of the crown, about the middle, gives an outline such as is exhibited in figure 4 View Figure , a section of the bottom of the crown, as in figure 5 View Figure , and a section of the broken extremity of the specimen, as in figure 6 View Figure .

The measurements of this specimen are as follows:—Length of the enamelled surface, 13 lines; greatest breadth at the lateral angles of this surface, 5 1/2 lines; diameter at base of crown, from within outwardly, 5 lines; diameter, laterally or antero-posteriorly, 4 lines.

Three much worn specimens of teeth of Trachodon , ( figs. 7—15 View Figure ,) are apparently the remains of fangs; the crowns or portions of the teeth faced with enamel having been worn away. The specimens have the form of transverse fragments of a parallelogram, with concave sides, and with one border bevelled off. The triturating surface ( figs. 9, 12, 15 View Figure ,) is concave, and presents a slightly elevated crucial ridge, with smaller diverging branches. The ridge is of a harder substance than the including dentine, and was no doubt intended to preserve a rough condition of the triturating surface as this is worn away. The under part of the specimens, ( fig. 8 e View Figure ,) is more or less hollowed, apparently from the pressure of succeeding teeth.

The length of the specimens is from 3 to 4 lines; the breadth of the triturating surface, from the parallel sides, from 2 1/2 to 3 lines.

Two additional specimens, ( figs. 16—20 View Figure ,) found with the preceding, may perhaps belong to a different animal, but it is quite probable also that they belong to a different part of the jaws of the same animal.

One of these specimens, ( figs. 18—20 View Figure ,) consists of the crown of a tooth with a small portion of one side broken away. The crown is a broad four-sided pyramid, with an acute summit rising to a short point. The outer surface, as it is presumed to be, is nearly vertical, devoid of enamel, and elevated into a longitudinal ridge on one side, as represented in figure 20 View Figure . This surface has been slightly roughened, but is worn smooth for part of its extent from attrition of an opposing tooth. The inner surface, ( fig. 18 View Figure ,) is concave, and elevated into a longitudinal ridge, opposite that on the outer surface; besides which, it has three short ridges extending from the summit of the tooth. On the unbroken side of the specimen, it is likewise embraced by a ridge, curving fromthe summit to the base of the crown. The unbroken side of the latter, ( fig. 19 View Figure ,) is triangular, convex, and tuberculated; is separated from the inner surface of the tooth by the curving ridge just mentioned; and from the outer surface by a ridge, which is transversely notched in the manner of the lateral borders of the teeth of Iguanodon . Below this side of the crown, the base of the specimen presents a sort of osseous envelope or thickening, which becomes obsolete on the outer face of the specimen. The base of the crown beneath and on each side is hollowed, apparently from the pressure of three successors.

The length of this specimen, on the outer side, as represented in figure 20 View Figure , is 5 1/2 lines; the breadth, 4 lines; the width at base, 4 3/4 lines.

Another specimen consists of the longitudinal fragment of a tooth, as represented in figure 16 View Figure . The triturating surface, ( figure 17 View Figure ,) is level and smooth, and corresponds with the transverse section of the fragment. This section is quadrate, with one of the sides formed by the broken border of the tooth. The other sides are concave, with the intervening angles prolonged; one of them being bevelled, and the other doubly so. The base of the fragment is enveloped in a thick, rugged osseous layer.

Explanation of Figures, Plate 9.

Figures 1—20, Teeth of Trachodon mirabilis .

Figures 1—6, of the size of Nature.

Figures 7—20, magnified two diameters.

Figure 1. Inner view of an inferior tooth, exhibiting the lozenge-shaped enamel surface divided by a median carina. The form of the fang restored in outline.

Figure 2. Lateral view of the same specimen, exhibiting the roughened outer surface, and at a a portion of the surface impressed by the crown of a lateral successor.

Figure 3. Outer view of the same specimen.

Figure 4. Section of the crown at the position marked b, fig. 1.

Figure 5. Section at the position marked c, fig. 1..

Figure 6. Section at the broken extremity d, fig. 3.

Figure 7. Remains of a much worn tooth, apparently from the upper jaw, external view.

Figure 8. Internal view of the same specimen, exhibiting at e the hollowed base.

Figure 9. Triturating surface of the same specimen, exhibiting the crucial ridge of harder dentinal substance.

Figures 10, 11, 12. Similar views to those last indicated, of another tooth.

Figures 13, 14, 15. Similar views of a third tooth.

Figure 16. Outer view of the remainder of a much worn tooth; the base enveloped by a thick osseous crust-

Figure 17. Triturating surface of the same specimen.

Figure 18. A slightly worn tooth, of peculiar form; apparent inner view.

Figure 19. Lateral view of the same specimen.

Figure 20. Outer view.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |