Miniopterus natalensis (A. Smith, 1833)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5735202 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5735334 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E84887F9-FFD8-D656-0A33-FC7219C93D12 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Miniopterus natalensis |

| status |

|

24. View Plate 53: Miniopteridae

Natal Long-fingered Bat

Miniopterus natalensis View in CoL

French: Minioptéere du Natal / German: Natal-Langfllgelfledermaus / Spanish: Minidptero de Natal

Other common names: Natal Bent-winged Bat

Taxonomy. Vespertilio natalensis A. Smith, 1833 ,

“ South Africa,—towards Natal [= KwaZulu-Natal].”

Miniopterus natalensis was the main sub-Saharan representative of the former schreibersii complex. Later restriction of schreibersii to the circum-Mediterranean Basin made natalensis the taxonomic reference name for medium-sized Miniopterusin much ofAfrica. Nevertheless, preliminary genetic studies have shown that it is actually formed by a complex of species whose situation is still far from clear. On top of this confusion,it is possible that M. natalensis can be confused with M. inflatus in areas where there is only one species of medium size. At present, the two subspecies found farthest from the type locality, villiersi from Upper Guinea in West Africa and arenarius from Kenya and Ethiopia, are considered valid species. Taxonomy of M. natalensis needs additional research. Monotypic.

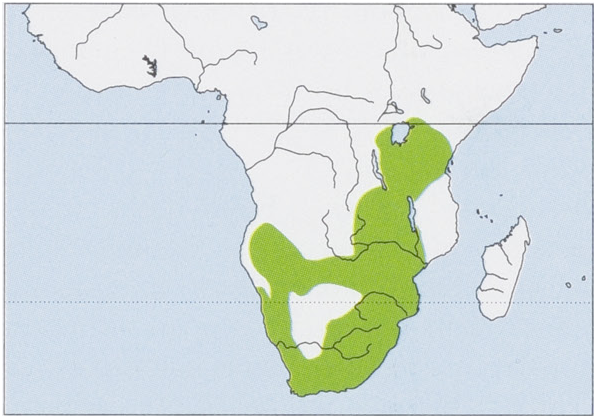

Distribution. E Africa ( Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, and Tanzania) and S Africa (SE DR Congo, Angola, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Swaziland, and Lesotho). Nevertheless, species assignment of the populations from E Africa needs genetic confirmation. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 55-6-68 mm, tail 46-55-5 mm, ear 9-5— 12 mm, hindfoot 8-10 mm, forearm 42-48 mm; weight 9-4-13 g ( South Africa). Dorsal pelage is dense, velvety, and usually very dark brown to grayish black (gray morph) or rusty red to rusty brown (orange morph). Ventral pelage is slightly paler than dorsum. Mid-dorsal hairs (7-9 mm long) are unicolored or with slightly paler tips. Wing membranes and uropatagium are very dark gray, blackish brown, or black. Ears are small, and tragus (4-7 mm) is relatively long with two-thirds parallel-sided, posterior margin becoming convex near rounded tip. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 46 and FN = 50.

Habitat. Temperate, subtropical, and tropical habitats from sea level up to elevations of ¢. 2200 m. Found in Mediterranean-type shrublands (fynbos) or woodland savanna (bushveld) up to c¢. 1000 m in South Africa and in wet Afromontane forest at 2200 m in Rwanda (Volcanoes National Park) and Tanzania (Mount Kilimanjaro). Found in arid open acacia savanna, thorn savanna, and mopane savanna at 1000-1300 m in Namibia and in miombo woodlands at 1000-1600 m in DR Congo (Shaba region).

Food and Feeding. The Natal Long-fingered Bat feeds on insects captured in flight. It has intermediate wing loading (10-7 N/m?) and intermediate aspect ratio (7); these wing characteristics allow good performance when flying in cluttered edges but also in more open areas. In Knysna Forest ( South Africa), its main prey was Diptera, Hemiptera, and Coleoptera (23-28% biomass), followed by Lepidoptera (19%) and Hymenoptera (3%). In Algeria Forest Station (Western Cape Province of South Africa), almost one-half of the diet consisted in Diptera , a third Hemiptera, and much smaller proportions of Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Trichoptera. In De Hoop Nature Reserve ( South Africa), it foraged exclusively over a temporary pond (vlei), with kloofs (steep ravines) leading away from it, and immediate surroundings, but no individuals were observed over farms or Mediterranean-type shrublands (fynbos) away from the vlei. In this area, preliminary results show that diet consisted mainly of Lepidoptera , Diptera , and Hemiptera. Average consumption per night per individual was 1-7 g (c.15% of body weight) in winter, whereas it was 2-4 g (20% of body weight) in summer. Winter population was estimated at ¢.20,000 individuals, suggesting consumption of 34 kg of insects/night. Summer population increased to ¢.200,000 bats that could consume 480 kg of insects/night. These figures give a total of 94 metric tons oftotal insect consumption/year by this one colony.

Breeding. Natal Long-fingered Bats are seasonally monoestrous, with only one young per year per female; twins are rare, with only one case in more than 150 pregnant females from South Africa. During the reproductive cycle, there is a period of delayed implantation lasting 2—4 months throughout the wide latitudinal distribution of the Natal Longfingered Bat. As a consequence of delayed implantation, time elapsed between copulation and parturition increases with increasing latitude and length of unfavorable cold winters. The species is an example of how reproductive flexibility allows colonization of areas with changing latitude, temperature, rainfall, and food availability from temperate to tropical environments. In Shaba ( DR Congo, 11° S, 1000-1500 m), copulation/fertilization occurs in April, implantation of the embryo at the end ofJuly (with ¢.3 months delay), and births in midto the end of October at beginning of rainy season (i.e. c.6 months from mating to birth). In Zimbabwe (18-19 S), copulation/fertilization take place from mid-April to mid-May, implantation in early July (with c.2-5 months delay), and births between late October and mid-November (6—7 months from mating to birth). In Transvaal (25° S, South Africa), copulation/fertilization peaks in late-March, implantation in late-July (with c.4 months delay), and births in November (c.8 months from mating to birth). In KwaZulu-Natal ( South Africa, 30° S), copulation/fertilization occurs in April, implantation in mid-August (c.4 month delay), and births starting in early December (7-5 months from copulation to birth). In general, deliveries take place in wet seasons in subtropical zones ( DR Congo, Malawi, and Zambia) and at the end of the cold season and beginning of rains in temperate zones ( South Africa). In East Cape ( South Africa), the mating period is not very synchronized and takes place during four weeks in April-May, and implantation is synchronized among all females, probably related to increasing daylength, resulting in synchronized births. Fetal growth during the final month of pregnancy can vary among years to adapt to increased availability of food as a result of the onset of rains. During years when rains are delayed, development offetusesis also delayed.

Activity patterns. In South Africa, peak nightly activity of Natal Long-fingered Bats occurs during the first 2-3 hours after sunset and another secondary peak during the last three hours before sunrise, with some activity throughout the rest of the night. Weather influences activity, and heavy rains shorten or preventflights. In October—January, activity patterns of males and females differed. Females tended to leave roosts first at night and return later in the morning, and males were most active during the middle of the night. Greatest nocturnal activity of females is due to increased food and water requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Females have delayed implantation that can last several months in all sites where reproduction was studied. This delay is associated with winter when females go into hibernation in temperate regions. Similar dates of torpor/hibernation were found in several temperate locations in South Africa but also in mountain areas of Namibia and DR Congo at lower latitudes. Intensity of torpor/hibernation is not well studied. For example, in De Hoop Guano Cave (Western Cape Province, South Africa), winter nocturnal activity occurs at sea level but is very reduced. Although diurnal torpor has been observed in Namibia and DR Congo, nocturnal activity is still possible. The Natal Long-fingered Bat mostly uses caves as daytime roosts, but unused mines and tunnels are also used. Availability of suitable roosting sites seemsto be a critical factor in determining its distribution. Echolocation calls have downward FM signals, with end frequencies of 43-47 kHz, peak frequencies of 47-6-50-9 kHz, and durations of 3-9—6-1 milliseconds.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Natal Long-fingered Bats occur in metapopulations that occur in a large territory in which there are several shelters (caves, etc.) that are used throughout the year by members of the population according to their energy requirements, availability of food resources, and characteristics of roosts (mainly temperature). In general, breeding females select warm shelters near areas with abundant food resourcesto facilitate development of young. In winter or unfavorable periods, they choose shelters with cold and stable temperatures to be able to hibernate or at least have daytime torpor. These different requirements generate seasonal movements among shelters that can be considered as regional migrations. Seasonal migration is more than 150 km and mainly involves pregnant females; movements occur between caves located on the southern Transvaal Highveld and northern Transvaal Bushveld where wintering and maternity colonies are formed, respectively. These northerly migrations occur from late winterto late spring. Late summer migrations occur in the opposite direction and involve females and weaned young. A genetic study throughout South Africa distinguished three populations: one in the north-east, one in the south, and another in the north-west. It was found that both sexes are strongly philopatric to their natal subpopulations and gene flow is restricted among subpopulations. For the north-western population, some individuals moved ¢. 560 km from Koegelbeen to Steenkampskraal to hibernate—a considerably longer distance than the one recorded in the former Transvaal. Wing morphology of the Natal Long-fingered Bat, with higher aspect ratio that improves flight efficiency over long distances, could have resulted from selective pressure for long-distance migration.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List.

Bibliography. Anciaux de Faveaux (1977 1978), Baeten et al. (1984), Bernard (1980, 1994), Bernard & Cumming (1997), Bernard & Happold (2013f), Bernard et al. (1996), Churchill et al. (1997), Crawford-Cabral (1989), Goodman, Ryan et al. (2007), Happold & Happold (1990), Hayman et al. (1966), Herselman & Norton (1985), Jacobs (1999a, 2000), Kityo & Kerbis Peterhans (1996), McDonald et al. (1990a, 1990b), van der Merwe (1973a, 1973b, 1975, 1981, 1987), Miller-Butterworth, Eick et al. (2005), MillerButterworth, Jacobs & Harley (2003), Monadjem, Griffin et al. (2017c), Monadjem, Taylor et al. (2010), O'Shea & Vaughan (1980), Rautenbach et al. (1993), Schoeman & Jacobs (2003, 2008), Smith (1833-1834), Stoffberg et al. (2004), Voigt et al. (2014).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Miniopterus natalensis

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Vespertilio natalensis

| A. Smith 1833 |