Miniopterus orianae, Thomas, 1922

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5735202 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5735290 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E84887F9-FFD1-D650-0AF7-F98A10E337E2 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Miniopterus orianae |

| status |

|

14. View Plate 52: Miniopteridae

Australian Long-fingered Bat

Miniopterus orianae View in CoL

French: Minioptére d'Oriana / German: Australische Langflligelfledermaus / Spanish: Miniéptero de Oriana

Other common names: Australian Bent-winged Bat, Northern Bent-winged Bat; Australasian Bent-winged Bat (oceanensis), Oriana’s Long-fingered Bat (orianae)

Taxonomy. Miniopterus orianae Thomas, 1922 View in CoL ,

“Casuarina Bay,” Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia.

Miniopterus orianae was previously in the schreibersii complex as M. schreibersii blepotis , but genetic studies have shown that this medium-sized Miniopterus from Australia is neither related to M. schreibersii from Europe nor to M. blepotis from Java. Despite these advances, the situation of the former “schreibersit” in Australia cannot be considered resolved. Because there are three clear mitochondrial lineages provisionally considered as subspecies,it is possible that future more inclusive studies will elevate them to a specific rank. Three subspecies recognized.

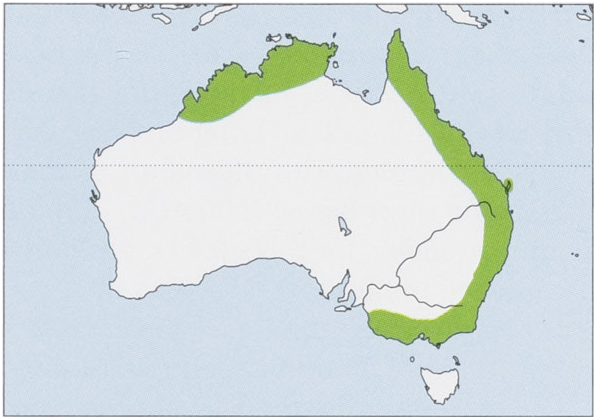

Subspecies and Distribution.

M.o.orianaeThomas,1922—NEWesternAustraliaandNNorthernTerritory.

M. o. oceanensis Maeda, 1982 — E Australia from Cape York in Queensland (including Fraser I) to Castlemaine in Victoria .

Distribution of bassanii and oceanensis overlap in W Victoria , with both subspecies recorded from four caves in the Otways/Camperdown/Lorne area. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 47-63 mm, tail 43-58 mm, ear 7-2-13-5 mm, forearm 43-2-49-7 mm; weight 8:6-16 g for nominotypical orianae . Other two subspecies are somewhat larger (forearm 43-3-50-6 mm), and all three subspecies differ in measurements of their skulls and skeletons. Dorsal pelage of the Australian Long-fingered Bat is dark brown,slightly lighter on venter. It occasionally has a reddish morph. Subspecies orianae is paler. Wing membranes are very dark, almost black. Ears are small, and tragus (3-4-7-3 mm) is somewhat curved and rounded at tip.

Habitat. Wide variety of habitats, including rainforests, wet and dry sclerophyllous forests, monsoon forests, open woodland, paperbark ( Melaleuca , Myrtaceae ) forests, and open grassland. Radio-tracked Australian Long-fingered Bats foraged predominantly along a forested ridgeline and also extensively used wetlands. Limited foraging oc-curred in open pastures and pine plantations. All known roosts are underground, predominantly in limestone caves but also in lava tunnels, coastal cliff rock crevices, and man-made tunnels. In the Northern Territory, a colony of more than 5000 Australian Long-fingered Bats occupy a large steel grain silo in an unused shed.

Food and Feeding. The Australian Long-fingered Bat is an aerial hawker, with medium-to-high values of wing loading (9-7 N/m?) and aspect ratio (6-7) that allow fast and direct flight, typical of foraging in open spaces. In woodland sites, it usually forages above the canopy but can fly closer to the ground in more open areas. Individuals are constantly in flight while foraging, sometimes meandering between areas after 5-15 minutes of foraging, or flying to a particular foraging area, remaining there for one or more hours. The Australian Long-fingered Bat is a moth specialist, and Lepidoptera appeared in 91% of fecal samples, Hymenoptera (Formicidae) in 20%, and Blattodea, Orthoptera, Hemiptera, and Coleoptera in 10%. In feces collected under colonies, as many as 20 species of moths were identified from eight different families ( Hepialidae , Geometridae , Anthelidae , Saturniidae , Sphingidae , Notodontidae , Arctiidae , and Noctuidae ) and a praying mantis.

Breeding. The Australian Long-fingered Bat is seasonally monoestrous, with one young per pregnancy. Spermatogenesis in males begins at the end of November and December in the east coast of Australia (c. 30° S), and testes reach their maximum development in April. Sperm are very abundant in epididymides from May to mid-July. Females have a silent heat (ovulation without fertilization), similar to that in the Little Long-fingered Bat ( M. australis ) at the same latitude but which occurs two months before mating. Copulation takes place mostly between mid-May and the first one-half of June, and egg fertilization occurs immediately. Embryo goes through delayed implantation until the end of hibernation in August when gestation effectively begins. Maternity colonies are formed in October-November, and births occur in December and early January. Young are born naked, can fly at c¢.7 weeks old, and reach adult size at c.10 weeks old. Females give birth first in their second year of life. In subspecies bassanii at 37° S, the cycle is similar, but mating takes place mainly in April-May, with the peculiarity that in the same colony, births can vary widely between years from October to December. In tropicallatitudes, mating occurs mainly in September and births in December, with no apparent delay in implantation. Known longevity records are 20-5 years and 18 years for two reproductively active females.

Activity patterns. Most Australian Long-fingered Bats emerge between 19 minutes before sunset and 22 minutes after sunset. Half an hour before start of emergence, individuals increase their activity inside the cave, with frequent flights to the entrance of the roost. Activity of the Australian Long-fingered Batis bimodal. Individuals return to the roost normally at ¢.00:00-01:00 h, and they rested for c.1 hour before leaving again to forage until just before dawn. Heavy rain delays emergence and foraging activity. The Australian Long-fingered Bat uses warmer roosts during breeding and cooler roosts for hibernation. Temperatures of a maternity cave at Naracoorte (South Australia) were ¢.30°C, up to 10°C warmer than another similar cave close-by with no bats. It has been suggested that temperature differences are caused by heat generated by bats (200,000 bats in the maternity colony) and accumulated guano deposits. The Australian Long-fingered Bat is one of the few species of bats for which activity in the roost has been studied. Individuals divided their time among rest (62%), grooming (16%), and active (22%). Levels of rest were high during the day compared with preemergence and night. Individuals were active significantly less during the day than at other periods (pre-emergence and night). Grooming was significantly higher during pre-emergence than during the night, and it was minimal during the day. The highest levels of activity (mostly grooming) were found in larger clusters, perhaps reflect ing increased parasite load. The Australian Long-fingered Bat decreases its activity in winter and enters torpor. Torpor is longer in places with relatively cold winters. There is hardly any information about the duration of torpor and existence of true hibernation. In New South Wales and near the Australian coast, individuals are active year-round and weigh c.14-15 g in May-June, while in the tablelands (1000 m) at that time, individuals bats weigh 17-18 g due to fat they accumulate to survive winter with reduced activity. Echolocation calls have downward FM signals. Mean frequency and frequency of the knee respectively of the different subspecies are: orianae 50-50-7 kHz and 50-1-51-8 kHz; bassanii 47-5—47-9 kHz and 48-6—-49 kHz; oceanensis 45-3—-45-5 kHz and 45-7-46 kHz.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Australian Long-fingered Bats have large home ranges, and they can travel long distances, with lactating females repeatedly moving 23-25 km from a maternity cave to foraging areas. One radio-tracked male was found 35 km from his day roost. Populations are organized like those of other species of Miniopterus . Each population has a main refuge where the maternity colony is formed and several secondary refuges within a radius of 100-300 km of the main one that are used by non-breeding individuals or outside the breeding period. Movements among populations are infrequent and represent less than 1% in the more than 2000 movements recorded from marked bats in New South Wales, Victoria , and South Australia. Longest movement detected was 1300 km. Maternity colonies are mostly made up of females that come to these refuges in October-November from secondary roosts. When nursing ends in March, the colony breaks, with adult females leaving first and then young. Maternity colonies are formed by both sexes in subspecies bassanii. These maternity colonies usually have several thousand individuals but can exceed 10,000 individuals. In the case of bassanii, the maternity colony of Naracoorte has reached 100,000-200,000 individuals.

Status and Conservation. Not assessed on The IUCN Red List. The Australian Longfingered Bats was included in Schreibers’s Long-fingered Bat ( M. schreibersii ), which is classified as Near Threatened. Subspecies orianae and oceanensis of the Australian Longfingered Bat probably do not have important conservation problems, but subspecies bassanii was listed as critically endangered under Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act in 2007. There are three maternity caves of bassanii: one near Warrnambool, one near Cape Bridgewater (both in Victoria ), and one near Naracoorte in South Australia. In the last 50 years, the population near Naracoorte has declined from 100,000-200,000 individuals estimated in 1963 to 25,000 - 35,000 in 2011. The Warrnambool population is thought to have declined from 15,000 to 10,000 individuals over the same period.

Bibliography. Baudinette et al. (1994), Cardinal & Christidis (2000), Churchill (2008), Codd et al. (2003), Conole (2000), Dwyer (1963a, 1963b, 1964, 1966b, 1969), Furman, Oztun¢ & Coraman (2010), Lumsden & Jemison (2015), Maeda (1982), MillerButterworth et al. (2005), Rhodes (2002), Richardson (1977), Sramek etal. (2013), Thomas (1922), Wilson (2003).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Miniopterus orianae

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Miniopterus orianae

| Thomas 1922 |