Diparinae Thomson, 1876

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.1647.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9CDBECB7-17F1-4B0B-B577-CE29B34AA89A |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D40DA74B-DE4D-5463-AE8F-648DFEDEB948 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Diparinae Thomson |

| status |

|

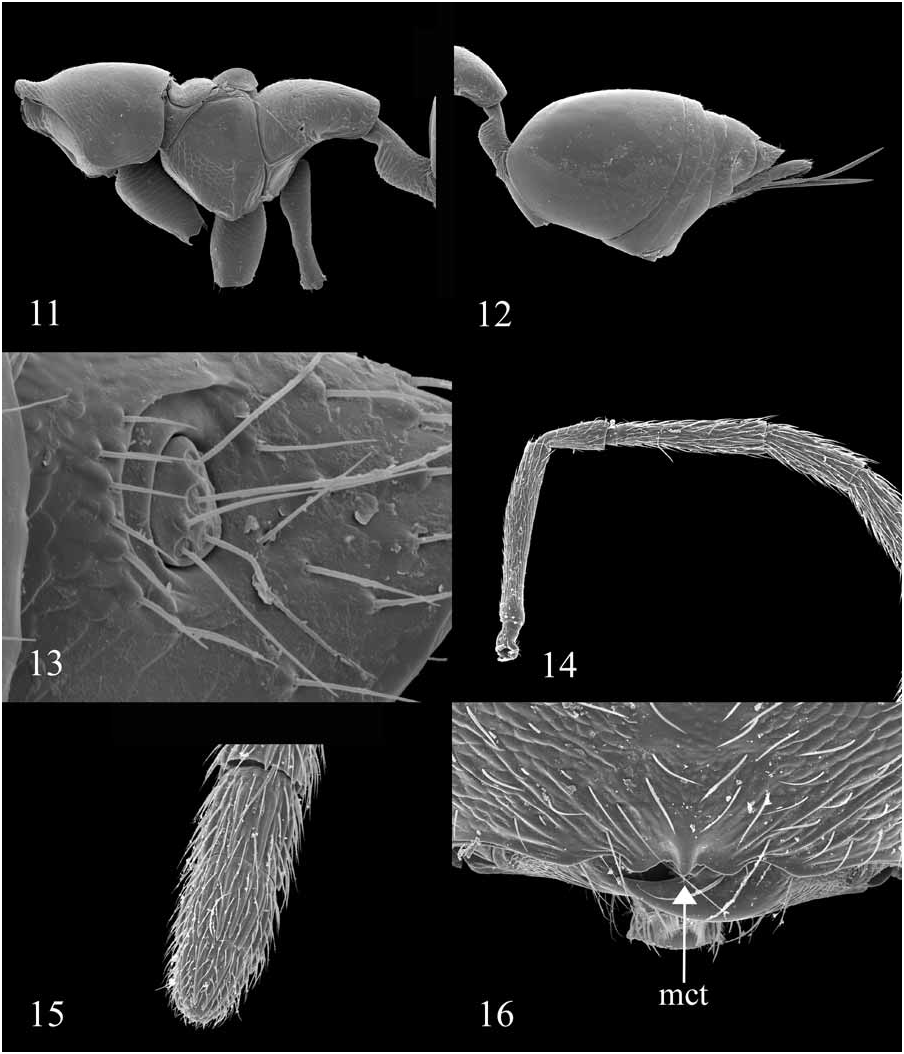

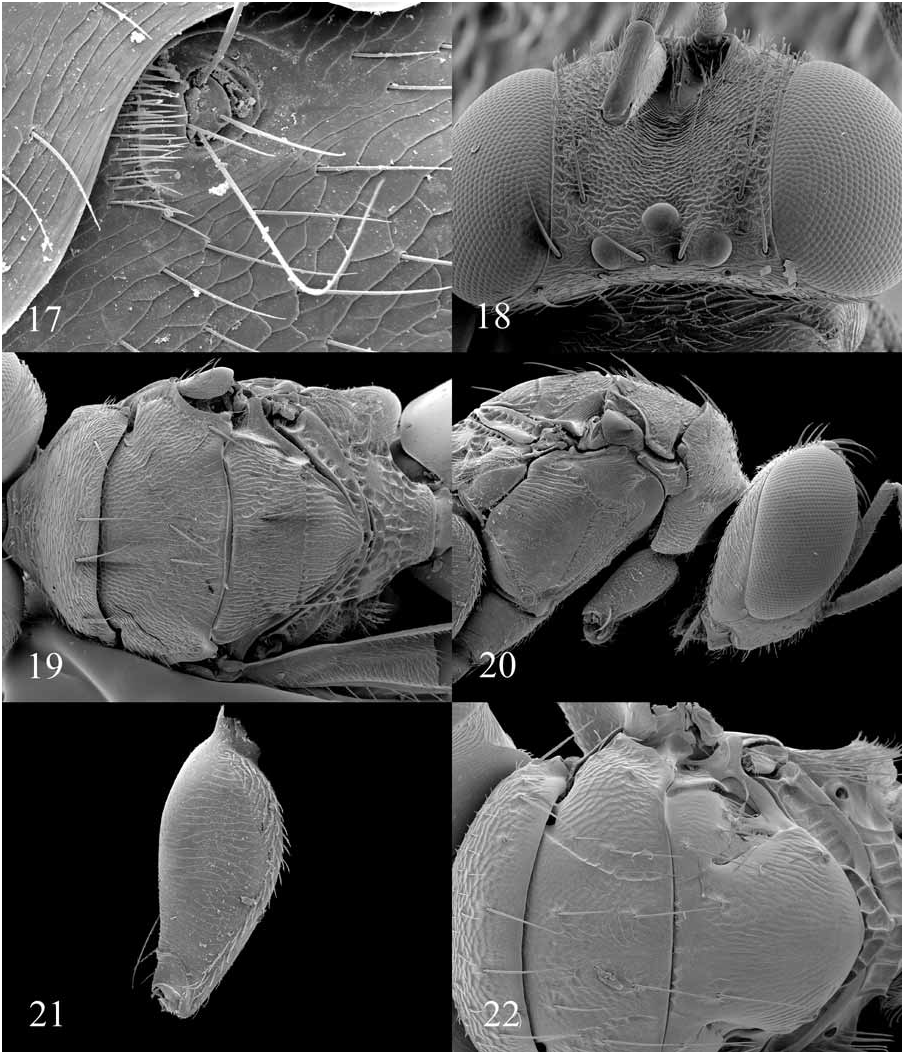

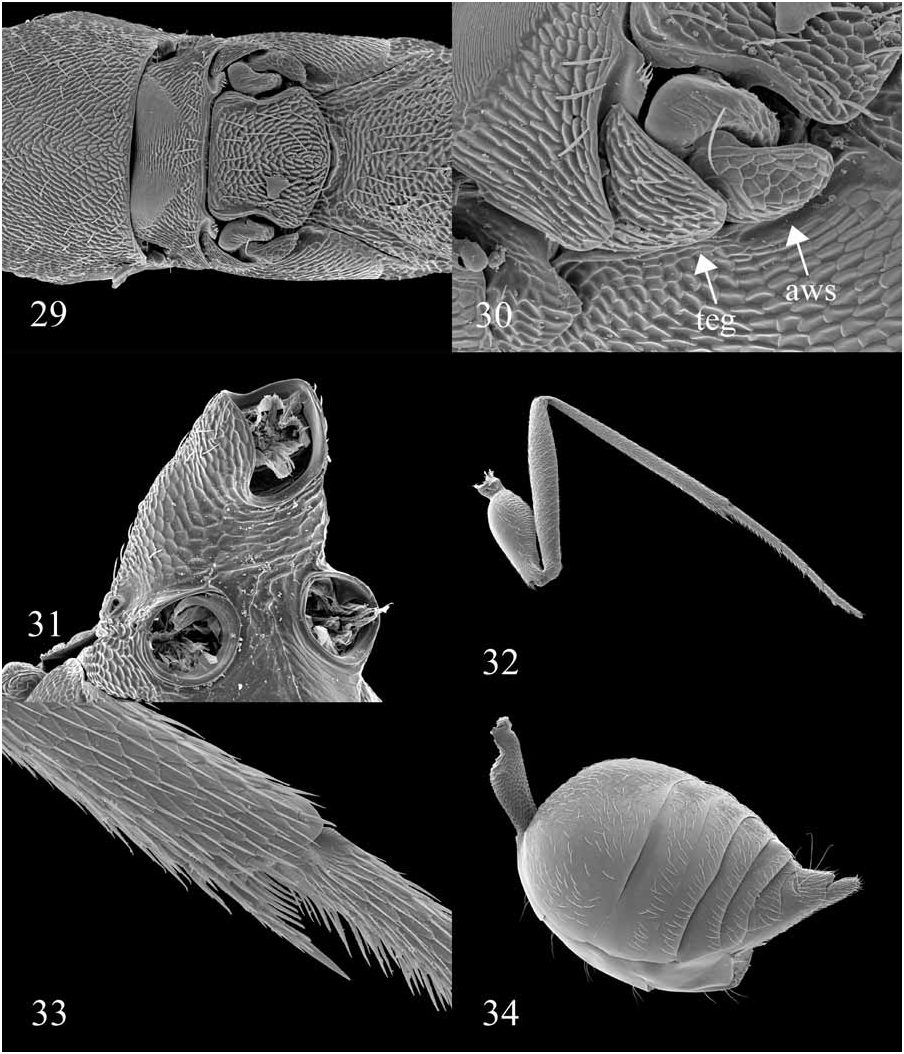

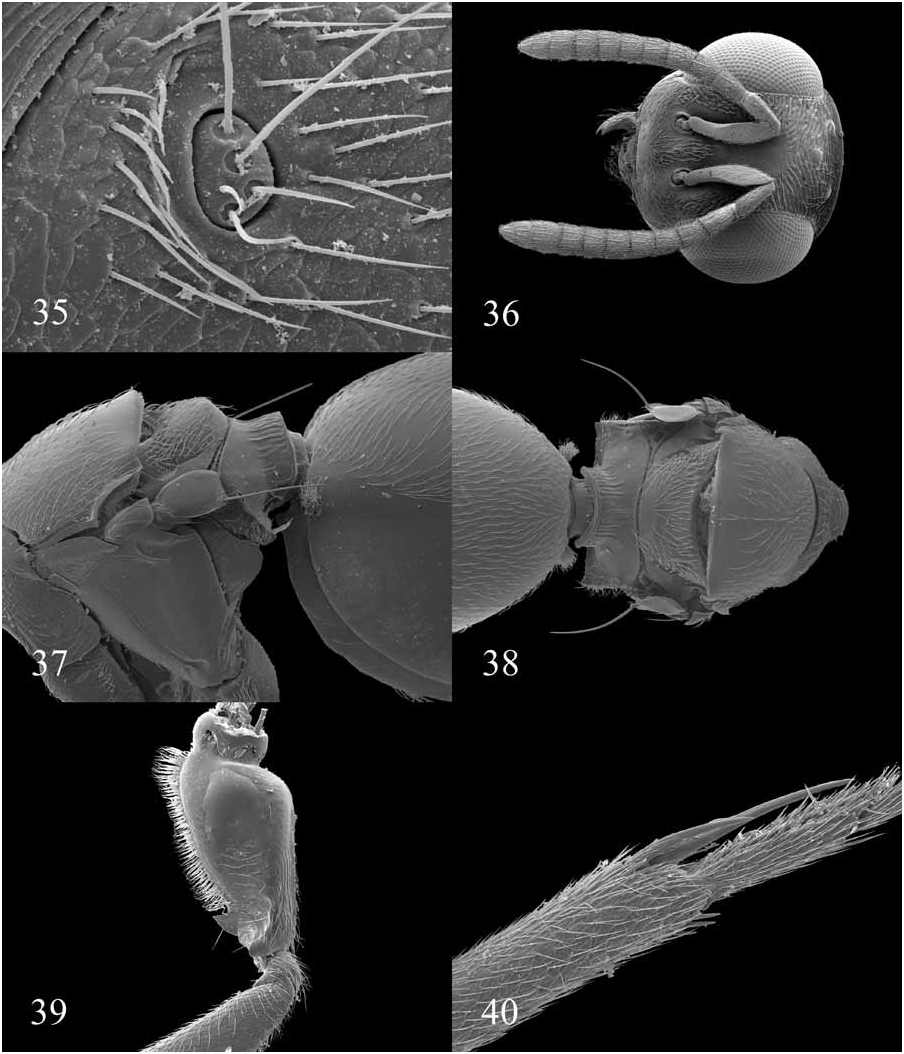

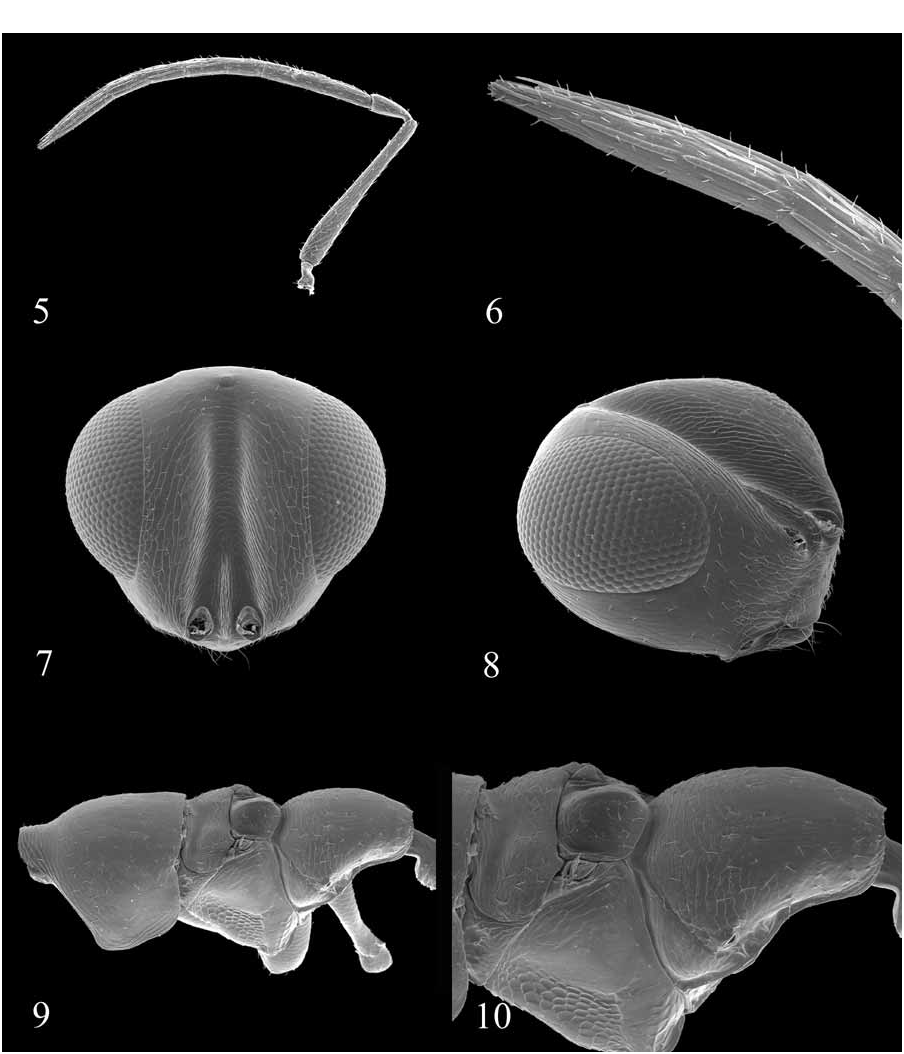

Diagnosis: Diparinae can be diagnosed by a combination of two features: presence of a cercal brush ( Figs. 13 View FIGURES 11–16 , 17 View FIGURES 17–22 , 34 View FIGURES 29–34 , 35 View FIGURES 35–40 , 41 View FIGURES 41–46 ) and absence of a smooth, convex dorsellum ( Figs. 10 View FIGURES 5–10 , 19 View FIGURES 17–22 , 29 View FIGURES 29–34 , 38 View FIGURES 35–40 , 48, 50, 51, 52 View FIGURES 47–52 ). Additionally, the vast majority of diparines have a GT1 expanded to cover at least 1/2 the metasoma ( Figs. 12 View FIGURES 11–16 , 34 View FIGURES 29–34 ) and transverse striations on the posterior margin of the metacoxa ( Figs. 21 View FIGURES 17–22 , 28 View FIGURES 23–28 , 32 View FIGURES 29–34 , 54 View FIGURES 53–58 ). Females are often apterous or brachypterous.

Taxonomic history: Thomson (1876, 1878) first described the group as “subtribus Diparides ” within Pteromalidae . Ashmead (1904) treated Diparinae as a subfamily of Pteromalidae and Lelapinae as a subfamily of Miscogasteridae based on the median clypeal tooth found in Lelaps . Peck (1951) proposed the tribe Diparini and placed it within Sphegigasterinae. Bouček (1954) synonymized the two subfamilies of Ashmead, without referencing Peck. Delucchi (1962) kept Bouček ’s subfamily status, but returned Diparini to tribal status and created a new tribe, Lelapini . He separated these tribes based on differences of the clypeus, pronotum, antennae, and bristles, although he did not qualify these differences. Hedqvist (1969) retained the two as separate tribes without referencing Delucchi’s identical tribal classification (as noted in Heydon and Bouček (1992)). Hedqvist included Lelaps Walker and the Hawaiian genera ( Calolelaps Timberlake , Mesolelaps Ashmead , Neolelaps Ashmead , and Stictolelaps Timberlake ) in Lelapini , while he placed the remaining genera in Diparini . Heydon and Bouček (1992) also noted that it appeared that Hedqvist had replaced the clypeal tooth character of Ashmead with brachyptery versus macroptery, as Hedqvist considered Spalangiolaelaps Girault (which has wingless females and a median clypeal tooth) to be part of Diparini . Hedqvist (1971) added a third tribe, Netomocerini, which contained only the genus Netomocera Bouček. Although he defined the tribe, none of the characters he listed were unique to Netomocera within Diparinae . Yoshimoto (1977) followed the classification of Hedqvist (1969, 1971), apparently also unaware of Delucchi’s (1962) proposal. Bouček (1988) proposed that the three tribes were unnecessary, and Lelapini and Netomocerini should be synonymized within Diparini . He erected a second tribe, Lieparini , for the aberrant genus Liepara Bouček. Heydon and Bouček (1992) followed Bouček’s (1988) tribal classification based on the presence of intermediates between the three tribes Diparini , Lelapini , and Netomocerini.

Discussion: The monophyly of Diparinae excluding Lieparini has been previously discussed in the Monophyly of Diparinae section. Based on these results the tribe Lieparini is removed from Diparinae and becomes unplaced within the Pteromalidae .

Biology: Although the first diparine was described over two hundred years ago, virtually nothing has been known about their biology. The first host was reported by Bouček (1988), in which an undescribed Indian species of Parurios was reared from a curculionid ( Coleoptera ) feeding on the roots of Cyperus . Since most female diparines are collected in forest leaf litter, and the only published host record is a curculionid, it has often been extrapolated that the entire subfamily parasitizes soil-inhabiting Coleoptera (e.g., Bouček 1988). In accordance with this hypothesis, Texas A&M entomologists reared Lelaps sp. from boll weevil relatives in southern Mexico (J. Woolley pers. comm.). Weevil parasitism certainly does not apply to all diparines, however, as an undescribed species of the African Myrmicolelaps was reared from mantid egg cases (Prinsloo pers. comm.), and an additional undescribed species was reared from a tsetse fly puparium ( Glossinidae : Glossina ). These data suggest that “typical” diparines may primarily parasitize beetles (and more specifically weevils), as has been suggested in the literature for some time. However, some morphologically bizarre diparines also possess deviant biologies, and parasitism of beetles certainly does not extend throughout the subfamily.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.