Cercopithecus diana (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863269 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFF5-FFF1-FA27-669AFE2DF7AA |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Cercopithecus diana |

| status |

|

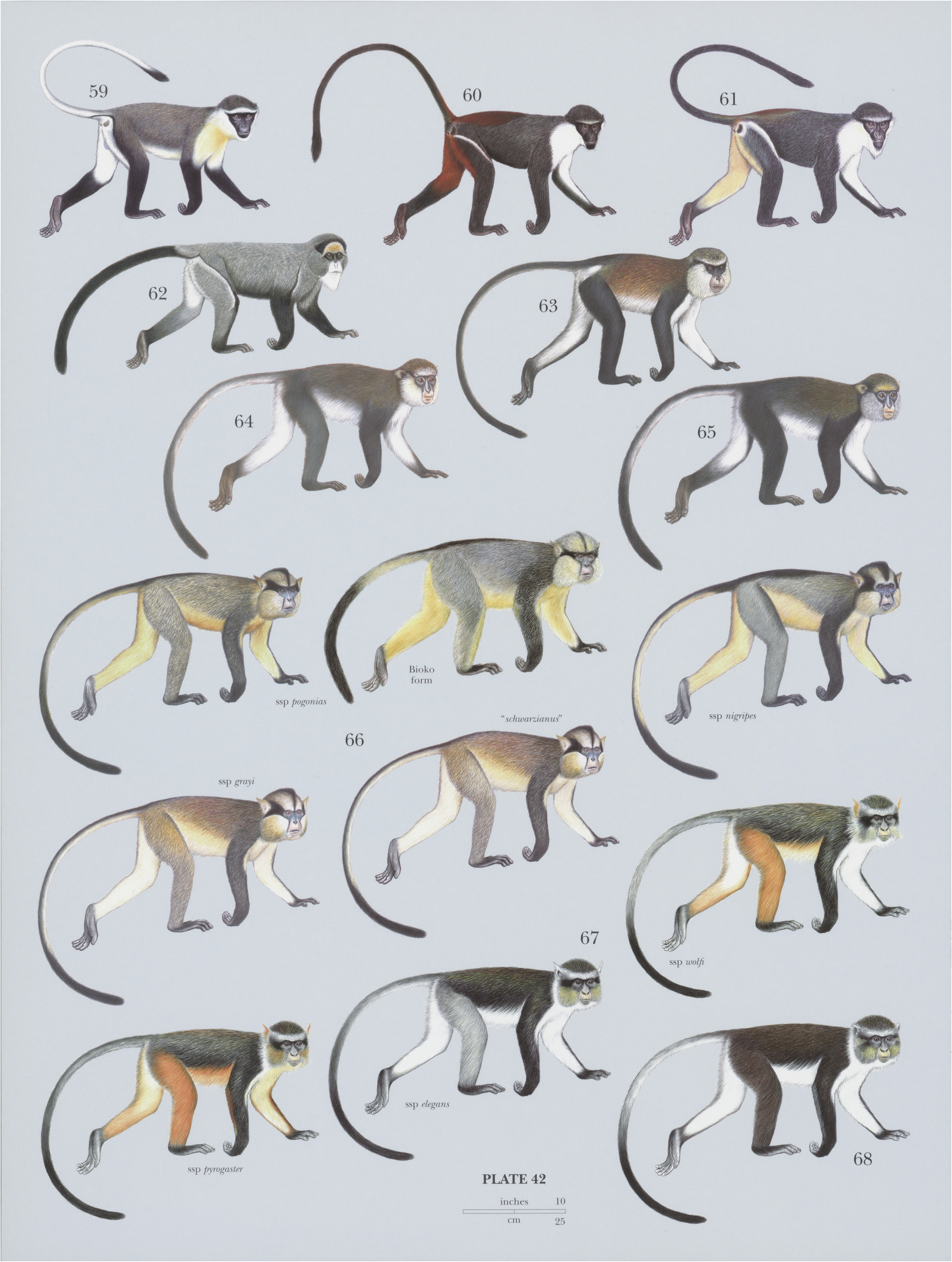

60. View Plate 42: Cercopithecidae

Diana Monkey

Cercopithecus diana View in CoL

French: Cercopitheque diane / German: Diana-Meerkatze / Spanish: Cercopiteco de Diana

Other common names: Diana Guenon

Taxonomy. Simia diana Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

Guinea (probably Liberia).

C. diana and C. roloway comprise the diana species group. Monotypic.

Distribution. S Guinea (Forécariah Priovince), Sierra Leone, Liberia, and SW Ivory Coast (W of the Sassandra River). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 50-60 cm (males) and 42-45 cm (females), tail 85 cm (males) and 70 cm (females); weight 5-2 kg (males) and 3-9 kg (females). Together with the Roloway Monkey ( C. roloway ), the Diana Monkey is the largest of the forest guenons. Individuals are brightly colored, with strikingly patterned coats. Fur is speckled purple and gray, with a broad chestnut-brown saddle on lower back. Throat, chest, and anterior surfaces of upper arms are white, sharply demarcated from the dark color on other surfaces. Lower legs, belly, and tail are black, and buttocks and inner surfaces of thighs are a deep orange-red. An oblique white stripe runs along each outer thigh. Faceis black, and forehead is framed by a thin whitish crescent (with some reddish hairs intermixed). A short, square “goatee” hangs from the chin; it is white, fringed with black. Individuals raise their long tails in a high arching curve when moving.

Habitat. Primary and old secondary lowland moist forest, gallery forest, and semideciduous forest near rivers. Diana Monkeys travel and forage mainly in the forest canopy. They are rarely found in degraded forest, but they are able to survive in lightly logged forest if the canopy remains.

Food and Feeding. The Diana Monkey is highly frugivorous; individuals studied in Tai Forest National Park spent 59% oftheir time feeding on fruits. Commonly eaten fruits are those of the canopy trees Sacoglottis gabonensis ( Humiriaceae ) and Dialium aubrevillev ( Fabaceae ), besides those of the liana Landolphia hirsuta ( Apocynaceae ) and the stilt-rooted tree Uapaca guineensis ( Euphorbiaceae ). Flowers and leaves are seasonally important as a standby when fruits are scarce. Insects are also an important component of the diet, more so than in many other guenons, and they spend long periods carefully searching the foliage of canopy trees for insect prey.

Breeding. Although reproductive patterns of Diana Monkeys have not been comprehensively studied, young infants (light brown to gray in color) have been observed most frequently in the dry months ofJanuary-February on Tiwai Island in Sierra Leone, suggesting that they have a December—February birth peak. The gestation period is 5—6 months. Mothers usually give birth to a single infant and carry it ventrally, at first supported by hand. Females become sexually receptive about once a month and do not exhibit a genital swelling. Sexual maturity is most likely reached at 3-5 years for females and 4-5-6 years for males. Individuals may live more than 30 years; one captive individual lived forjust over 35 years.

Activity patterns. Diana Monkeys are active, arboreal primates that spend most of their time in the middle and upper forest canopy. Forms of locomotion include walking and running (¢.70%), climbing quadrupedally (c.20%) through the forest canopy and leaping between canopy gaps (c.10%). Although the Diana Monkey usesall forest strata and occasionally moves on the ground, individuals spend most of their time above ground and use large boughs, especially for traveling, more than do the smaller guenons. As diurnal animals, groups spend the night in the topmost layer of the canopy, descending to the middle canopy by day to feed. Forty to 45% of their active time is spent feeding and foraging and 25% moving, although there is considerable variation in time allocation across groups, seasons, and years.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Movements,traveling distances, and home ranges of the Diana Monkey are reported to be highly variable and depend on factors such as group size, habitat features, and resource availability. The average distance traveled in a day is reported to be 1-1-5 km, and home ranges are 29-93 ha. Females and young chase their opponents in neighboring groups at territorial boundaries. Females also emit a “chatter-scream” that incites louder calls and displays by males in the group. Social groups tend to be relatively large, with 15-30 individuals. Typically, groups contain just one adult male, 5-13 adult females, and young. Solitary males that have not succeeded in joining a group move around on their own, occasionally joining groups of other species. Diana Monkeys are notably less affiliative with members of their group compared with other guenons. Males, in particular, exhibit low levels of integration into their group; females groom other females and young, but males are reported to never receive any grooming. Higher levels of agonistic interactions are also ascribed to the level of competition for food within groups. The main predators of Diana Monkeys are Leopards (Panthera pardus), Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), eagles, and humans. Research by K. Zuberbtuihler and colleagues, using playbacks of vocalizations of Leopards and crowned hawk-eagles (Stephanoaetus coronatus), showed that Diana Monkeys gave alarm calls that were specific for Leopards and different from those for eagles. They would often approach the source of the calls, letting other group members know of the danger and which predator had been seen. Leopards and eagles hunt by surprise, and alarm calls result in them calling off a hunt. The approach of humans and a playback of social screams of Chimpanzees, however, generally did not result in alarm calling. Both are pursuit predators, and the monkeys’ alarm calls would evidently draw their attention. Diana Monkeys instead keep quiet and try to hide and slip away unnoticed. Leopards are also predators of Chimpanzees, and Chimpanzee leopard-alarm screams (as opposed to social screams) stimulate bouts of Leopard alarm-calling by Diana Monkeys. Diana Monkeys travel with groups of Campbell's Monkeys ( C. campbelli ) and respond to their alarm calls, which are also predator specific. Although evidently serving as alarm calls for predators, the loud calls of Diana Monkeys differ between sexes, and males show a peak in loud calling in the early evening that is not related to predators. They have a slightly different structure (a different number ofsyllables), group members do not respond with their own calls, and loud calling in this situation is believed to play a role in the male’s defense of his females and territory.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Diana Monkey is listed as Class A in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Habitat loss and hunting have led to a 30% decline in Diana Monkeys over the past 30 years (three generations). Habitat loss 1s driven mainly by logging and clearing land for agriculture and charcoal production. Such deforestation continues to reduce habitat availability for Diana Monkeys. They are dependent on tall mature forest that is becoming increasingly degraded and fragmented. Diana Monkeys are also more vulnerable to hunting than other guenons because of their larger size, noisy vocalizations, and bright colors. They occur in a number of protected areas: Ta Forest National Park in Ivory Coast; Tiwai Island Wildlife Sanctuary and the proposed Gola and Loma national parks in Sierra Leone; and Sapo National Park in Liberia. Despite the protected status of these areas and official prohibition of hunting, Diana Monkeys are continuing to lose their habitat and are being harvested at unsustainable levels.

Bibliography. Noé & Bshary (1997), Buzzard (2004, 2006), Buzzard & Eckardt (2007), Byrne et al. (1983), Groves (2001, 2005b), Grubb et al. (2003), Hill (1991, 1994), Holenweg et al. (1996), Honer et al. (1997), Kingdon (1997), McGraw (1996a, 1998a, 1998b, 2002, 2007), McGraw & Oates (2007), Napier (1981), Oates (1988b, 2011), Oates & Whitesides (1990), Oates, Gippoliti & Groves (2008b), Zuberbuhler (2000, 2002), Zuberbuhler et al. (1997).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Cercopithecus diana

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Simia diana

| Linnaeus 1758 |