Theropithecus gelada (Ruppell, 1835)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863239 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFE7-FFE3-FA3E-62F3F8CCF841 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Theropithecus gelada |

| status |

|

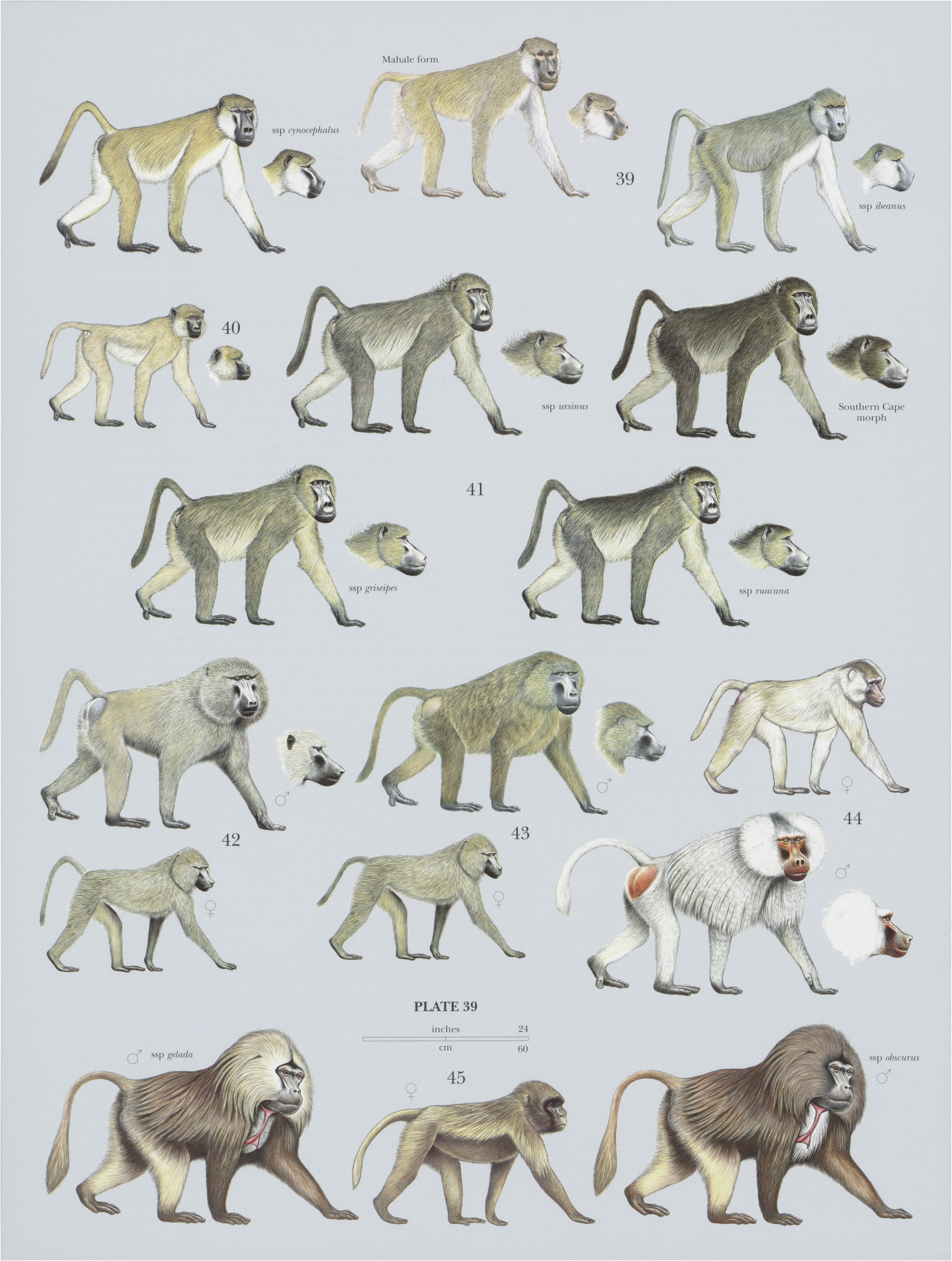

45. View Plate 39: Cercopithecidae

Gelada

Theropithecus gelada View in CoL

French: Gélada / German: Dschelada / Spanish: Gelada

Other common names: Gelada Baboon; Northern Gelada (gelada), Southern Gelada ( obscurus)

Taxonomy. Macacus gelada Ruppell, 1835 View in CoL ,

Ethiopia, Haremat, Semyen, and Gojjam.

There is a need for further research on the intraspecific taxonomy of 7. gelada , especially the distributional ranges of subspecies. A possible third subspecies was discovered in 1989 in Arsi Province, but it has yet to be formally described. This “Arsi Gelada ” is possibly synonymous with the described form senex and is found in south-western Ethiopia (Arsi Province) east of the Rift Valley along the Webi-Shebelle Gorges. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

1. g. gelada Ruppell, 1835 — Ethiopia (N of Lake Tana and W of the Takezé River).

1. g. obscurus Heuglin, 1863 — Ethiopia (S of Lake Tana and E of the Takezé River). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 69-75 cm (males) and 50-65 cm (females), tail 46— 50 cm (males) and 33-41 cm (females); weight 20-30 kg (males) and 12-16 kg (females). The Gelada is a large, heavily built primate. Both sexes are covered with thick, sooty yellow-brown fur dorsally, with darker limbs and a grayish white underside. Muzzle is rounded and marked by deep lines, and nostrils are unusual in being upturned and set well back on the face. Adult male Geladas are almost twice the size of females (female body mass is 59% of male body mass) and have a heavy mane around their head and shoulders, which in older individuals hangs almost to the ground. Adult males also have long, curving cheek whiskers and pale eyelids, in stark contrast to the otherwise dusky face. Buttock pads are purplish-gray and rather flat; they do not fuse across the midline in adult females, as they do in adult males. Skin below the buttock pads is bare (edged with vesicles in the female) and incorporates a pair offatty pads below. Tail is shorter than the head-body length and thickly tufted at the tip. Perhaps the most interesting feature in both male and female Geladas, however,is the conspicuous patch of pinkish-red skin on the chest (heart-shaped in males, hourglassshaped in females, and edged with white or gray fur ) and an additional, smaller crescent on the throat. Mammae are close to the midline. Hands are ideal for all manner of precise manipulation; they are equipped with highly opposable thumbs and finely proportioned (though notably shortened) index fingers, believed to be an adaptation for manual “grazing.” In the “Northern Gelada ” (T. g. gelada ), the mane is dark brown, while the area surrounding the chest patch (which is not extensive) is iron-gray. The “Southern Gelada ” (1. g. obscurus ) is similar to the Northern Gelada , but it has a darker mane and extensive, pure white fur surrounding the chest patch.

Habitat. High montane regions including grassland, scrubland, and some types of woodland at elevations of 1400-4400 m. Steep cliffs provide sleeping roosts. Geladas feed mainly on the flat margins of high grass plateaus, with Agrostis and Festuca grasses (both Poaceae ) and giant Lobelia (Campanulaceae) groves. Geladas are poor tree climbers and are almost entirely terrestrial, spending 99% of their time on the ground. This is partly a consequence of their extreme dietary specialization as a grazer.

Food and Feeding. Grasses are the dietary staple of Geladas, supplemented with roots, bulbs, flowers, seeds, leaves, fruits, and animal prey (including insects). Geladas feed primarily on leaves of grasses. They show some morphological and physiological characteristics that are believed to be adaptations to their grass diet. When feeding, individuals typically shuffle along on their well-cushioned rumps (referred to as “shuffle-gait”) plucking blades of grass and occasionally digging around with the help of their long sharp fingernails. During dry seasons when there is heavy overgrazing by livestock, or when Gelada bands are very concentrated in one area, subterranean stems and rhizomes are also excavated. Fruits and invertebrates are eaten opportunistically, and cereal crops may be taken where agriculture encroaches into their habitats.

Breeding. Female Geladas have a 32-36day reproductive cycle, and the peak is marked by an outline of whitish, fluid-filled beads around the chest and genitals. The gestation period has not been exactly determined, although it appears to be 175-188 days, as in other baboons. One, rarely two, offspring are born per pregnancy. Some studies found birth peaks in July-December, but others did not find any seasonality of births. Offspring are nursed for well over a year, during which time the mother seems unable to reproduce again. Young Geladas are uniformly dark smoky-brown. Cases of infantcide have been reported. Expected life span is less than 14 years in the wild, although some individuals may live up to 20 years.

Activity patterns. Geladas are diurnal and terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Geladaslive in a multilevel or modular society with one-male units (OMUs) as the basal social entity, superficially similar to the social system of Hamadryas Baboons ( Papio hamadryas ). The OMUs contain one adult “leader” male and 1-12 (related) females (averaging 3-4) with their dependent offspring. Often, 1-5 additional males are attached to an OMU, called “follower” males. Males that are not leaders or followers of an OMU gather together and form relatively stable all-male units (AMUs). Two to 30 OMUs and an AMU comprise a band, which may have 30-260 individuals. Males from AMUs challenge OMU leader males from time to time, trying to take over a unit of females. During takeovers, the risk of infanticide is particularly high. There is even evidence that pregnant females abort if a takeover occurs. If the number of females in an OMU becomes too large, they sometimes split into two or more “daughter” units, which retain relatively close social relationships. The OMUs with such close social relationships are called “teams.” Bands stay within 2 km of escarpment edges, where they retreat at night or if alarmed. As a result, home ranges are linear, encompassing as little as 1-3 km? for a band’s core area (although their annual home range can be 70 km?®). In general, Gelada bands are less stable in their composition than are those of Hamadryas Baboons ; they are best regarded as a set of OMUSssharing a foraging area. At times,several bands may aggregate at sites where food is abundant. Up to 1000 Geladas can then be seen grazing together. Surveys in a number of areas suggest overall densities of 15-60 ind/km?, but densities within home ranges commonly exceed 70 ind/km?®.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List, including the subspecies obscurus , but the nominate subspecies gelada is classified as Vulnerable. The Gelada is listed as Class A in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Male Geladas have been regularly hunted by local Ethiopians, who use their enormous manes to make ceremonial headdresses. In the past, the numbers of adults may have been reduced as a result of selective shooting for their capes. There are historic records of capes being made into fur hats for tourists, but that no longer occurs because it is now extremely difficult for any tourist to leave the country with items made from Gelada skins. Although hunting may no longer be the main threat, they are still chased and shot as crop pests. Geladas have been trapped as laboratory animals in the past (e.g. 1200 individuals were imported into the USA in 1968-1973). Currently, the main threatis deterioration of their habitat and competition with domestic livestock and agriculture, resulting in significant habitat loss. Northern Geladas are known to occur in one protected area, Simien Mountains National Park, but Southern Geladas do not occur in any protected area. The proposed Blue Nile Gorges National Park and Indeltu (= Shebelle) Gorges Reserve would serve to protect a large part of the total population, which is currently estimated to be less than 250,000 individuals (more than 440,000 in the 1970s). The Indeltu Gorges Reserve would protect the unnamed subspecies.

Bibliography. Aich, Moos-Heilen & Zimmermann (1990), Aich, Zimmermann & Rahmann (1987), Alvarez (1973), Alvarez & Consul (1978), Beehner & Bergman (2008), Belay & Mori (2006), Belay & Shotake (1998), Bergman & Beehner (2008), Bergman et al. (2009), Bernstein (1975), Bramblett (1970), Cronin & Meikle (1979), Crook (1966), Dandelot & Prévost (1972), Dunbar (1973, 1977a, 1977b, 1978, 1979, 1980a, 1908b, 1982, 1983a, 1983b, 1983c, 1984, 1986, 1992), Dunbar & Bose (1991), Dunbar & Dunbar (1974a, 1974b, 1977, 1988). Dunbar et al. (2002), Frost et al. (2003), Gippoliti (2010), Groves (2001), Grueter & Zinner (2004), Grueter et al. (2012), Hill (1970), Iwamoto (1979, 1993), Iwamoto & Dunbar (1983), Iwamoto et al. (1996), Jablonski (1993), Jolly, C.J. (1972, 2007), Jolly, C.J. et al. (1997), Kawai (1979), Kawai et al. (1983), Kingdon (1997), Krebs (2011), Kummer (1975), Ludwig (1996), Matsuda et al. (2012), Matthews (1956), Mau, Johann et al. (2011), Mau, Stidekum et al. (2009), McCann (1995), Mekonnen (2009), Moos et al. (1985), Mori, A. & Belay (1990, 1991), Mori, A., Iwamoto & Bekele (1997), Mori, A., Iwamoto, Mori & Bekele (1999), Mori, U. (1979), Mori, U. & Dunbar (1985), Mori, U. et al. (2003), Nguyen Nga & Fashing (2012), Nievergelt et al. (1998), Ohsawa & Dunbar (1984), Pickford (1993), le Roux et al. (2011), Smith & Credland (1977), Snyder-Mackler et al. (2012), Swedell (1997, 2011), Yihune et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Cercopithecinae |

|

Genus |

Theropithecus gelada

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Macacus gelada

| Ruppell 1835 |