Papio anubus (Lesson, 1827)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863231 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFE5-FFE1-FFD9-6D89FC85F8C6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Papio anubus |

| status |

|

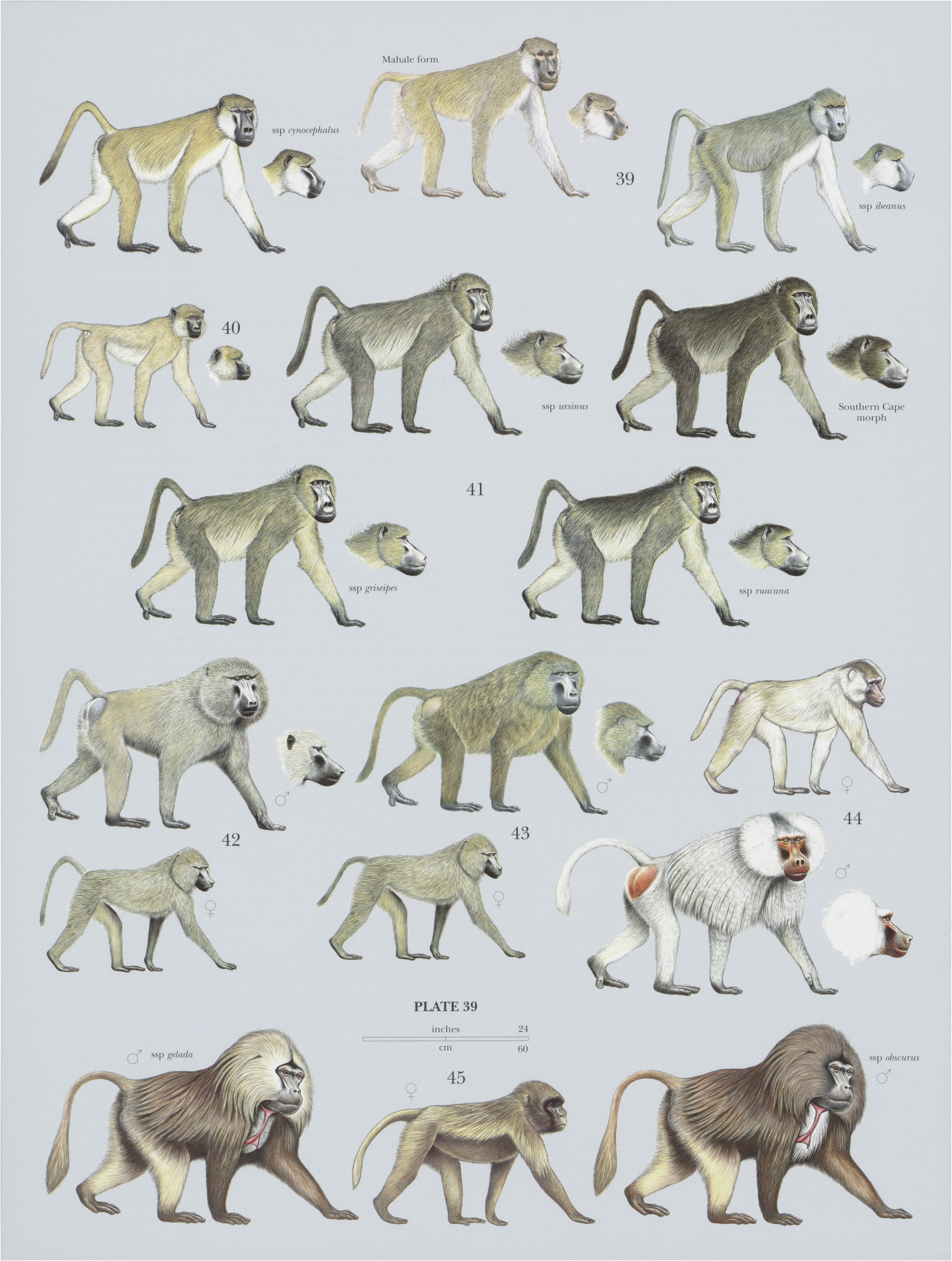

42. View Plate 39: Cercopithecidae

Olive Baboon

French: Babouin anubis / German: Anubis-Pavian / Spanish: Papion oliva

Other common names: Anubis Baboon

Taxonomy. Simia anubis Lesson, 1827 ,

Africa. Restricted by J. Anderson in 1902 to the Upper Nile.

P. anubis has regional differences in skull morphology and pelage color. Accordingly, a number of subspecies have been proposed (e.g. tesselatum), but currently none are recognized. Whether some forms would merit subspecies status needs further research. Wherever the distribution of this species encounters that of other baboon species, there are hybrid zones whit strong indications that P. anubis is still in a phase of active expansion. It forms a narrow hybrid zone with P. hamadryas below Awash Falls and elsewhere in northern Ethiopia and central Eritrea. It hybridizes with P. cynocephalus in Tsavo East National Park and Amboseli National Reserve in Kenya. There is a broad clinal hybrid zone of P. anubis x P. cynocephalus between Laikipia district, just to the north-east and east of Mount Kenya, and the Lower Tana River along the Kenya coast. Baboons in this more than 200km-wide region are intermediate and are difficult to allocate to either P. anubis or P. cynocephalus (baboons become increasingly “yellow-like” in their phenotypes toward the Kenya coast). P. anubis from Eritrea and Ethiopia carry maternally inherited mitochondria that are genetically closely related to P. hamadryas mitochondria. P. anubis in Kenya and Tanzania carry mitochondria closely related to P. cynocephalus mitochondria, indicating that male introgression by P. anubis might be the major form of hybridization. P. anubis x P. cynocephalus are also found elsewhere sporadically across the species contact zone in Kenya and Tanzania. It is possible that P. anubis has caused distributions of neighboring baboon species to contract. Hybridization with P. papio is not known for certain but is probable. Even hybridization with Theropithecus gelada has been observed in the wild. Monotypic.

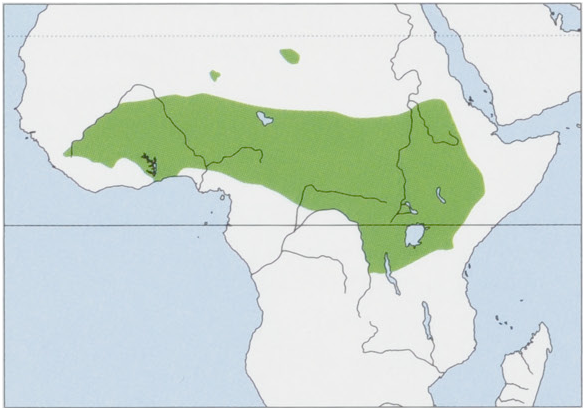

Distribution. Throughout the N savanna belt from Mali, Guinea, and Sierra Leone to W Eritrea and Ethiopia, and S into N & E DR Congo and NW Tanzania; isolated populations inhabit the Tibesti, Air and Ennedi massifs in the Sahara. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 55-90 cm (males) and 50-70 cm (females), tail 41-60 cm (males) and 38-46 cm (females); weight 22-30 kg (males) and 14-18 kg (females). Sexual dimorphism in the body weight of the Olive Baboons is pronounced; female body mass is only 52-55% of male body mass. Although variable in size and coloration,it is generally dark olive-brown above with black hands and feet. Pelage has a “pepper-and-salt” or speckled appearance. Adult male Olive Baboons have a mane that is restricted to the foreparts and grades into the shorter body fur (i.e. not sharply set off). Skin of the face and around the buttock pads is purplish-gray to blackish, and the bare area on the rump is smaller than in Hamadryas (FP. hamadryas ) or Guinea ( P. papio ) baboons. Nostrils are pointed and extend a little beyond the snout. Tail is carried directed up for the proximal one-fourth, then falls away in a characteristic “broken” fashion, similar to the tail carriage in the Yellow Baboon (PF. cynocephalus ). Ischial callosities in males form a single ridge, but in females, they are separated by the genitals. As in other baboons, female Olive Baboons develop prominent periovulatory sexual swellings. Infants are born with black natal coats that change to the adult coloration at 3-6 months of age.

Habitat. Semi-desert, thorn scrub, and open savanna to rocky hills, high-elevation forest, gallery forest, and rainforest at elevations up to 2500 m—the widest variety of habitats of all baboon species. Water is a limiting factor, and groups of Olive Baboons will travel long distances to find it. They readily live near and use cultivated lands.

Food and Feeding. Like other baboons, the Olive Baboon is an omnivorous opportunist. Its diet varies according to region and season and includes mainly fruits and leaves, along with flowers, tuberous roots, grasses, bark, twigs, sap, bulbs, mushrooms, lichens, seeds, shoots, buds, and animal prey (invertebrates, lizards, birds, and small mammals, as well as other primates such as green monkeys, Chlorocebus ). Resin, gum, and bark act as a fall-back foods in dry seasons. Swarming locusts and termites provide an occasional glut. Olive Baboons raid crops and garbage dumps.

Breeding. Female Olive Baboons reach menarche at 4-6 years old and have their first infant at 6-7 years old. Menstrual cycle length is 34-45 days, and the gestation period is 180-188 days. Births occur throughout the year, and interbirth intervals are 22-27 months. When a female is sexually receptive, males try to monopolize access to her. A male and a female form a temporary consortship (several minutes to days). Most mating happens during these consort periods. In multimale groups, the consorting male is often challenged by other males, and male consort partners may change several times during a female’s receptive cycle. Female Olive Baboons usually mate with several partners. Females give copulation calls, i.e. they vocalize during and shortly after copulation. Males mature at 7-10 years old. Most likely, male Olive Baboons take longer to become adults compared with male Hamadryas Baboons , but mature faster than male Yellow Baboons. Olive Baboons may live up to 30 years in the wild.

Activity patterns. Olive Baboons are diurnal and mainly terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home range sizes (4-44 km?®) and daily movements of Olive Baboons vary considerably depending on habitat, group size, and season. Home ranges of neighboring groups overlap, and groups may aggregate temporarily at sleeping sites. Daily movements are usually less than 7 km. Besides food, home ranges contain essential localized resources such as water and sleeping sites. Olive Baboons use large trees and rocks as sleeping sites. Like Chacma (FP. ursinus ) and Yellow baboons, Olive Baboons live in multimale-multifemale groups of 20-120 individuals. Groups in West Africa tend to be smaller (7-40 individuals) than those in East Africa (30-120 individuals). The ratio of adult males to adult females varies substantially (1:1-9), and there are usually more females than males. Groups are not substructured into one-male units, as in Hamadryas Baboons or Geladas ( Theropithecus gelada ), although solitary one-male units have been observed, most frequently in West Africa. Most females remain in their natal groups and form linear dominance hierarchies. High-ranking mothers support their daughters during rank conflicts, resulting in a dominance rank of the daughter just below the mother. Rank positions are “heritable,” and dominance relationships among matrilines within a group can remain stable over generations. Most males emigrate from their natal groups at 7-13 years of age. Secondary emigration into a third group has also been observed. Males also establish a dominance hierarchy that usually regulates access to receptive females. The dominant male of a group may sire most of the offspring during his tenure, but lower ranking males have been observed to form coalitions to challenge higher ranking males and to take over receptive females. The social network among related femalesis the most stable social structure in the group. Grooming and other affiliative behaviors are exchanged predominantly within these networks. Studies suggest that these tight relationships provide a fitness advantage for females. Females with a tighter network live longer and reproduce more successfully. Females and males may also form bonds outside sexual consortships, called “friendships.” These relationships likely benefit a female via protection for herself and her offspring against sexual harassment and infanticide by other males. The male benefits because it may protect its own offspring or it may invest in future sexual relationships with the respective females.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Olive Baboon is listed as vermin in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. It is very widespread and locally abundant, and although persecuted as a crop raider, trapped for biomedical research, and hunted for bushmeat, there are no major threats believed to be resulting in a range-wide population decline. Nevertheless, human-induced habitat loss and degradation impact Olive Baboons. Introduced infectious diseases affect local populations with high mortality rates. Local populations may be threatened. Isolated populations on the Saharan massifs, in particular, merit further research. Further studies also may reveal that certain forms of Olive Baboons are valid subspecies. Olive Baboons occur in many protected areas: e.g. Pendjari and West of the Niger national parks in Benin; West of the Niger National Park in Burkina Faso; Bénoué, Bouba Ndjida, and Waza national parks, Faro Reserve, and Kimbe River and Mbi Crater game reserves in Cameroon; Zakouma National Park in Chad; Garamba, Kahuzi-Biéga, and Virunga national parks and Tayna Gorilla Reserve in the DR Congo; Awash and Bale Mountains national parks, Stephanie Wildlife Sanctuary, and Menagesha-Suba National Forest in Ethiopia; Bui, Digya, and Mole national parks, Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve, Bomfobiri Willdife Sanctuary, and Willi Falls Reserve in Ghana; Marahoué, Comoé, and Mount Péko national parks in Ivory Coast; Lake Nakuru, Marsabit, Meru, Nairobi, Masai Mara, and Samburu national parks in Kenya; West National Park in Niger ; Cross River, Gashaka-Gumti, and Kainji Lake national parks and a number of game reserves and forest reserves in Nigeria; Akagera, Nyungwe Forest, and Volcanoes national parks in Rwanda; Dinder National Park in Sudan; Nimule National Park in South-Sudan; Arusha, Gombe Stream, Kilimanjaro, Lake Manyara, Serengeti, and Tarangire national parks in Tanzania; Kéran and Fazao-Malfacassa national parks and Koué Reserve in Togo; and Bwindi Impenetrable, Kibale Forest, Murchison Falls, and Queen Elizabeth national parks and Budongo Forest Reserve in Uganda.

Bibliography. Alberts & Altmann (2001), Aldrich-Blake et al. (1971), Anderson (1902), Balzamo et al. (1980), Barnett & Prangley (1997), Barton (1990), Bercovitch (1987a, 1987b, 1991), Bercovitch & Harding (1993), Bercovitch & Strum (1993), Berger (1972), Booth (1956a, 1956b, 1958b, 1979), Breuer (2005), Campbell, Teichroeb & Paterson (2008), Charpentier, Fontaine et al. (2012), Charpentier, Tung et al. (2008), Collins et al. (1990), Dandelot & Prévost (1972), Depew (1983), DeVore & Hall (1965), Domb (2000), Domb & Pagel (2001), Dunbar & Dunbar (1974a), Dutrillaux et al. (1979), Eley et al. (1989), Ey (2008), Ey & Fischer (2011), Ey et al. (2009), Fay (1988), Frost et al. (2003), Garcia et al. (2006, 2008), Gautier-Hion et al. (1999), Gilmore (1979), Grubb (2006), Grubb et al. (1998), Hapke et al. (2001), Harding (1973, 1976, 1977), Hendrickx & Kraemer (1969), Higham, Heistermann et al. (2008), Higham, Semple et al. (2009), Higham, Warren et al. (2009), Hill, C.M. (2000), Hill, W.C.0O. (1970), Huynen (1987), Isabirye-Basuta (2004), Johnson (1987, 1989), Jolly (1993, 1997/1998, 2007, 2012), Jolly & Phillips-Conroy (2003, 2006), Jolly et al. (1997), Kagoro-Rugunda (2004), Kahumbu & Eley (1991), Kingdon (1971, 1997), Krebs (2011), Kriewaldt & Hendrickx (1968), Kunz & Linsenmair (2007, 2008a, 2008b, 2010), Lejeune (1986a, 1986b, 1986¢, 1986d), Lemasson et al. (2008), Manzolillo (1986), Moore (1978), Mori & Belay (1990), Nagel (1973), Nash (1973, 1974, 1976), Newman et al. (2004), Nobimé et al. (2008), Nystrom (1992), Oates (2011), Okecha & Newton-Fisher (2006), Oyaro & Strum (1984), Packer (1975, 1977, 1979a, 1979b, 1980), Paterson (1973, 2006), Pfeyffers (1999/2000), Phillips-Conroy & Jolly (1981), Phillips-Conroy et al. (1992), Poché (1976), Ransom (1981), Rowell (1969), Samuels & Altmann (1986), Silk & Strum (2010), Sinsin, Téhou et al. (2002), Smuts (1985), Smuts & Nicolson (1989), Smuts & Watanabe (1990), Stark & Frick (1958), Strum (1987), Strum & Western (1982), Swedell (2011), Tung et al. (2008), Verschuren (1978), Vinson (2005), Warren (2003), Whiten et al. (1992), Wildman et al. (2004), Zinner, Buba et al. (2011), Zinner, Groeneveld et al. (2009), Zinner, Pelaez, Torkler & Berhane (2001).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.