Papio hamadryas (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863235 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFE4-FFE2-FAC5-6D63F6E1F92F |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Papio hamadryas |

| status |

|

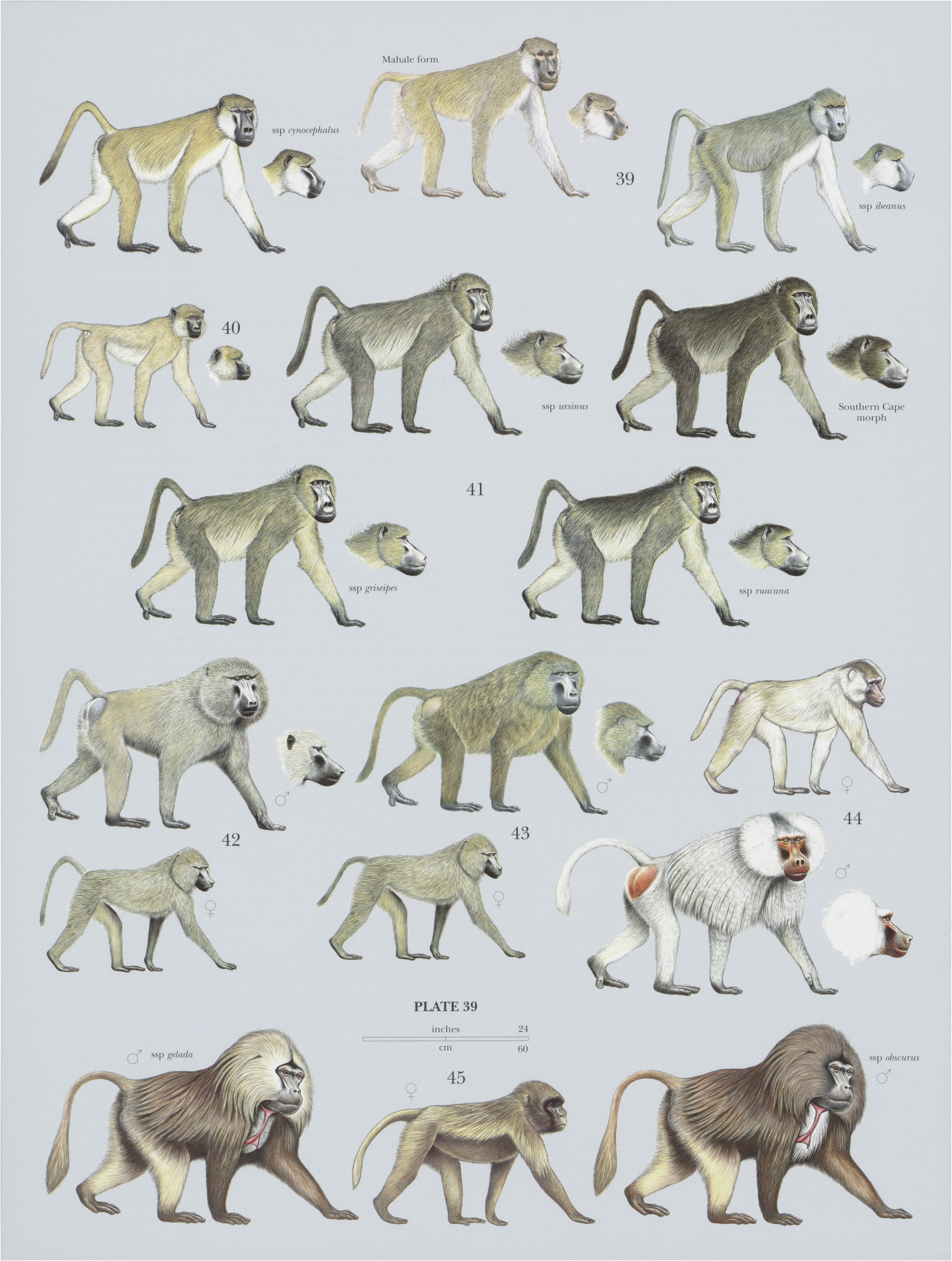

44. View Plate 39: Cercopithecidae

Hamadryas Baboon

French: Babouin hamadryas / German: Mantelpavian / Spanish: Papion sagrado

Other common names: Mantled Baboon, Sacred Baboon

Taxonomy. Simia hamadryas Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

Egypt.

P. hamadryas hybridizes with P. anubis in a narrow zone below Awash Falls and elsewhere in northern Ethiopia and central Eritrea. There are no consistent differences between African and Arabian populations. Monotypic.

Distribution. SW Saudi Arabia (up to Jeddah), W Yemen, NE Sudan (Red Sea Hills), E Eritrea, Djibouti, NE Ethiopia, and N Somalia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 70-95 cm (males) and 50-65 cm (females), tail 42— 60 cm (males) and 37-41 cm (females); weight 16.4-21.3 kg (males, up to 30 kg in captivity) and 10-15 kg (females). Male and female Hamadryas Baboons differ markedly in size and physical appearance; female body mass is 58% of male body mass. Males are ashy orsilvery-gray, with an enormous shoulder cape, mane, or mantle (in older individuals), reaching back to the rump and contrasting with very short hairs on the body and limbs. The mane bushes out to form white cheek whiskers, offset by darker and shorter crown hairs. Adult male Hamadryas Baboons are also typified by their massively built face and dagger-like upper canine teeth. Hands and feet are dark, and tail is tufted with white and held in a simple backward-pointing curve. Skin offace and earsis bright pinkish-red, as is the cushion-like skin around the buttock pads. H. Kummer in 1968 described an east-west distributional gradient in male face color in Ethiopia, with darker faces in the west and more light-red faces in the east. Females and young are drab olive-brown without a mane, and their faces and ears are grayish or dull flesh-colored, resembling females and juveniles of other baboon species. Skin of ischial callosities is similarly colored but not cushion-like. Neonates have light pink faces and black fur . Their fur changes color at 3-6 months old. Albinism has been reported (as evidenced by a painting of an albino male by the English artist George Stubbs).

Habitat. Rocky desert and semi-desert steppe, arid lowland savanna, cliff faces, and alpine grass meadows to 2600 m above sea level. In Eritrea, Hamadryas Baboons also use densely wooded areas (Semenawi Bahri). They appear to be seasonally migratory in at least some parts of their distribution in Ethiopia, where groups may move up into neighboring mountainous areas (up to 3300 m in Simien Mountains National Park) in the wet season. They are dependent on water and never found far from water sources. Hamadryas Baboons are sometimes called “desert baboons,” but this name seems to be unjustified because they occur in various habitats from dry coastal lowlands to humid montane forests.

Food and Feeding. Like all baboons, Hamadryas Baboons are opportunistic omnivores. Important foods include grass, grass seeds, rhizomes, roots, tubers, shoots, fruits (notably heglig Balanites , Zygophyllaceae , and buffalo thorn Ziziphus , Rhamnaceae ), young leaves, Acacia (Fabaceae) flowers, doum palm fruits ( Hyphaene thebaica, Arecaceae ), and animal prey (including insects and scorpions and small vertebrates such as lizards and small mammals). During daily foraging, they may move as much as 10 km, and they often make daily climbs of several hundred meters when they descend from their sleeping sites into deep valleys to drink and climb back up again in the afternoon to reach their sleeping cliff. In many places, the foraging behavior and diets of Hamadryas Baboons have changed in recent years because they use crops, garbage dumps, and most importantly, massive stands of the non-native prickly pears ( Opuntia sp. Cactaceae ). This plant provides a year-round food source, and because of its high water content,it is an additional source of water—a big advantage because access to water is a limiting factor in most parts of their distribution.

Breeding. Female Hamadryas Baboons reach sexual maturity at 4-5 years of age and give birth to theirfirst surviving infant at 5-7 years. Males reach adult size at 6-9 years of age but are capable of siring infants even earlier, although they have not yet developed the full attributes of an adult male (e.g. silvery gray shoulder mantle). Females have a 30-40day menstrual cycle. They exhibit a pink sexual swelling of the perineal skin when approaching ovulation. Its size fluctuates with concentrations of sexual hormones, reaching its peak around ovulation. Mating and births occur throughout the year, although a weak seasonal birth peak has been found in some studies. In Hamadryas Baboons ,it is typically only the adult leader male of a one-male unit that mates with the females. The gestation period lasts 165-184 days. Usually only a single young is born. Interbirth intervals average 22 months, but they tend to be much shorter in captivity. In the first weeks after birth, an infant is carried on its mother’s belly, and later it rides “jockey-style.” Offspring are nursed for 8-12 months. Instances of infanticide have been reported in free-ranging and captive populations. Life span in captivity is typically up to 30 years.

Activity patterns. Hamadryas Baboons are diurnal and terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home range sizes are 10-40 km? and may overlap extensively with those of other groups. Daily movements can be up to 20 km but are usually 6-8 km. Hamadryas Baboons normally spend nights on steep rocky cliffs, but they may also use trees on rare occasions. Their social system is characterized by a multilevel or modular social organization, consisting of three to five levels, superficially resembling the social system of the Gelada ( Theropithecus gelada ). The smallest social unit is the one-male unit or OMU, comprising an adult “leader” male, several females (1-9, typically 2-3) and their dependent offspring and sometimes one or two “follower” males. Follower males socialize with unit members, but mating is usually monopolized by the leader male. Several OMUs and additional “solitary” males (males that are not leaders or followers) form a clan. It is believed that clans are male kin-based. Several clans, OMUs, and solitary males together comprise the next higher level oftheir organization, the “band,” which can have more than 100 members. Individuals in a band share a common home range, largely synchronize their travel pattern, and use sleeping cliffs together. The band is mostlikely analogous to the multimale-multifemale groups of other baboon species. The largest grouping is the “troop,” which is an unstable aggregation of several bandsat sleeping sites, totaling several hundred individuals. At Filoha, Ethiopia, subsets of OMUs within clans suggest a fifth level of society in this population. In contrast to other baboon species where males usually leave their natal groups after reaching maturity, female Hamadryas Baboonsare transferred, often coercively, among OMUs by males within clans and bands, but occasionally also between bands. Males sometimes disperse. Most social behavior occurs within OMUs. Adult males show a ritualized greeting behavior (“notifying”), and they cooperate to coordinate their daily travel. The strongest social bonds are between adult females and their leader male within OMUSs, which is in contrast to the strong female—female bonds in other baboon species. Males herd their females aggressively, routinely chasing females and using visual threats and physical aggression (e.g. neck-bites) to control female movement and maintain OMU cohesion.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. The Hamadryas Baboon is classified as vermin in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Prior to 1500, its distribution extended into Egypt. The Hamadryas Baboon is of African origin, but how and when they dispersed into the Arabian Peninsula is still an open question. It is believed that they either crossed the Red Sea via a land bridge near Bab-el-Mandeb during glacial lowsin sea level, or they were transported by ancient Egyptians trading by sea with the Land of Punt. Hamadryas Baboons are rarely hunted, although the Oromo people traditionally use their skins for ceremonial wear. They are chased and occasionally shot or killed with poison as crop pests. In Eritrea, fat of the buttocks of Hamadryas Baboons is used in traditional medicine as a cure for sprain and pulled muscles. They were formerly trapped in large numbers for medical research; a large colony of Hamadryas Baboons, for example, was established 1927 in Sukhumi, Georgia (formerly USSR). The Hamadryas Baboon occurs in several protected areas: Awash National Park, Harar Wildlife Sanctuary, and Simien Mountains National Park in Ethiopia and Asir National Park in Saudi Arabia. It is also found in the proposed Yangudi Rassa National Park, a number of wildlife reserves in the lower Awash Valley in Ethiopia, and several proposed reserves in Eritrea. Part of the population in Awash National Park and other areas along the distributional border of the Hamadryas Baboon in Ethiopia and Eritrea are P. hamadryas x P. anubis (the Olive Baboon) hybrids. As in other baboon species, the conservation status of the Hamadryas Baboon is geographically ambivalent and needs a proper reassessment. Although locally abundant, they are seen as pests by local people and governments, and they have been extirpated from large parts of their former distribution, resulting in a significant population decline. The major threat is loss of habitat due to agricultural expansion and irrigation projects. In a mainly arid environment, many places where water could be found were converted into irrigated agriculture in the last 20 years, and given the dependence of Hamadryas Baboons on water, they were eliminated from these areas.

Bibliography. Abegglen, H. & Abegglen (1976), Abegglen, J.J. (1984), Al-Safadi (1994), Asanov & Mirvis (1972), Beehner & Bergman (2006), Bergman & Beehner (2004), Bergman et al. (2008), Biquand, Biquand-Guyot & Boug (1989), Biguand, Biquand-Guyot, Boug & Gautier (1992a, 1992b), Coelho et al. (1983), Colmenares (1991), Colmenares et al. (2006), Dandelot & Prévost (1972), Deputte & Anderson (2009), Drake-Brockmann (1910), Fernandes (2009), Fraser & Plowman (2007), Frost et al. (2003), Gomendio & Colmenares (1989), Groves (2001), Grueter & Zinner (2004), Grueter et al. (2012), Hammond et al. (2006), Hapke et al. (2001), Hill (1970), Jolly & Phillips-Conroy (2003, 2006), Jolly et al. (1997), Kamal & Boug (1996), Kamal, Boug & Brain (1997), Kamal, Boug, Brain, Ghandour et al. (1995), Kamal, Ghandour & Brain (1994), Kaumanns et al. (1989), Kingdon (1997), Krebs (2011), Kummer (1968, 1990, 1995), Kummer & Kurt (1963), Kummer et al. (1981, 1985), Kinzel et al. (2000), Lawson Handley et al. (2006), Matsuda et al. (2012), Mori & Belay (1990), Mori et al. (2007), Miller (1980), Nagel (1973), Newman et al. (2004), Nitsch et al. (2011), Nystrom (1992), Osborn & Osbornova (1998), Peldez (1982), Phillips-Conroy & Jolly (1981, 1986), Phillips-Conroy, Jolly & Brett (1991), Phillips-Conroy, Jolly, Nystrom & Hemmalin (1992), Pines & Swedell (2011), Pines et al. (2011), Romero & Castellanos (2010), Schreier (2010), Schreier & Swedell (2008, 2009, 2012), Shotake (1981), Sigg & Stolba (1981), Sigg et al. (1982), Stammbach (1987), Stark & Frick (1958), Stolba (1979), Sugawara (1988), Swedell (2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2011), Swedell & Saunders (2006), Swedell & Schreier (2009), Swedell & Tesfaye (2003), Swedell, Hailemeskel & Schreier (2008), Swedell, Saunders et al. (2011), Wildman et al. (2004), Winney et al. (2004), Woolley-Barker (1999), Yalden et al. (1977), Yamane et al. (2003), Zinner (1993), Zinner & Deschner (2000), Zinner & Palaez (1999), Zinner & Torkler (1996), Zinner, Buba et al. (2011), Zinner, Groeneveld et al. (2009), Zinner, Kaumanns & Rohrhuber (1993), Zinner, Krebs et al. (2006), Zinner, Peldez & Berhane (1999/2000), Zinner, Pelaez & Torkler (2001a, 2001b), Zinner, Schwibbe & Kaumanns (1994).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.