Papio papio (Desmarest, 1820)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863233 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFE4-FFE1-FFFC-6292F748F7D7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Papio papio |

| status |

|

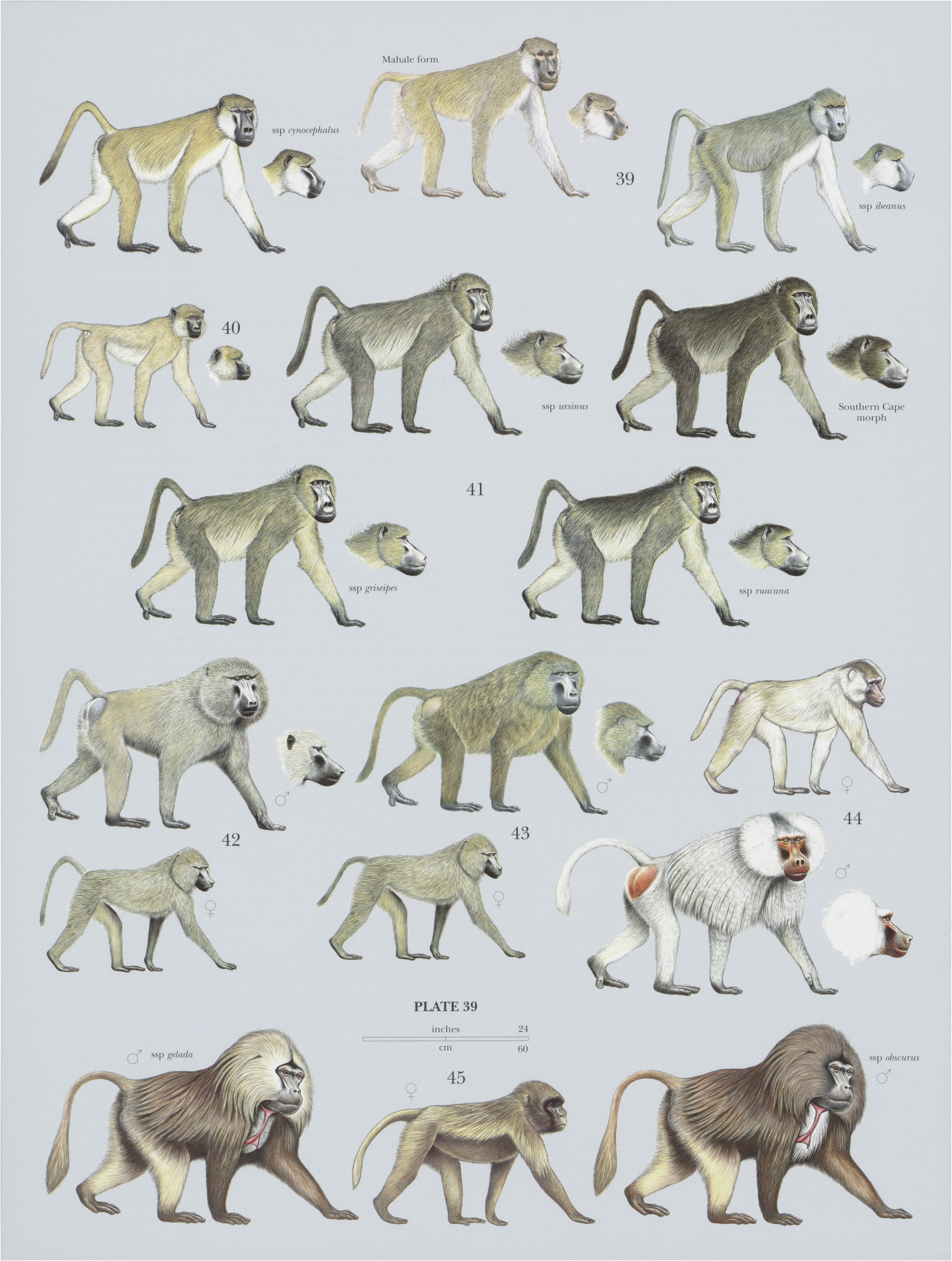

43. View Plate 39: Cercopithecidae

Guinea Baboon

French: Babouin de Guinée / German: Guinea-Pavian / Spanish: Papién de Guinea

Other common names: Western Baboon

Taxonomy. Cynocephalus papio Desmarest, 1820 View in CoL ,

Coast of Guinea.

Along its eastern limits, P. papio may hybridize with the larger P. anubis , but reliable information is lacking about the exact positions of these species’ distributional borders and possible interactions. Monotypic.

Distribution. S Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, W Mali, W Guinea, and NW Sierra Leone;its occurrence in W Liberia is highly unlikely. Found in extreme Western Africa, the N boundary of which (in Mali and Mauritania) is not completely known. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 43-86 cm (males) and 35-69 cm (females), tail 55-70 cm (males) and 43-56 cm (females); weight 17-26 kg (males) and 10-14 kg (females). The Guinea Baboon is a medium-sized baboon, with a uniformly reddishbrown body. Face and hands are blackish-red, upper eyelids are white, and ischial callosities are large and pinkish-gray. The Guinea Baboon is strongly sexually dimorphic, with males larger than females. In Niokolo-Koba National Park, Senegal, female body mass is, on average, only 59% of male body mass. Males also have a well-developed mane or cape on their shoulders that contrasts with shorter fur on the rump and limbs. Tail loops up and back evenly. Nostrils protrude beyond the end of the snout. Females develop sexual swellings of the perineal skin when sexually receptive.

Habitat. Humid coastal mangrove and Guinean forest to arid Sahelian steppe. Guinea Baboons occur in evergreen gallery forest, secondary forest, dry forest, light woodland savanna, and shrubland.

Food and Feeding. Similar to other baboons, Guinea Baboons are omnivorous, with fruits as their main food item. They also eat young leaves, seeds, grasses, flowers, tuberous roots, and animal prey (including invertebrates and vertebrates such as lizards, birds, and small mammals, e.g. young bushbuck, Tragelaphus). Guinea Baboons living near farms and plantations will eat rice, maize, yams, groundnuts, and other cultivated crops.

Breeding. There is no information available for this species.

Activity patterns. Guinea Baboons are diurnal and mainly terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Information on Guinea Baboons is scarce compared with other baboon species. Most data come from captive groups and from a few short-term field studies in Niokolo-Koba National Park. Their movements vary seasonally between 1000-13,000 m/day (mean 4400 m), and home range size is ¢.3800 ha. Guinea Baboons most likely live in a multilevel or modal social organization, with a complex fission-fusion dynamic on a daily and seasonal basis. The largest aggregations of more than 300 individuals are observed during the rainy season. Observations of captive Guinea Baboons suggest that the basal social unit is the one-male unit (OMU, one adult male and several females and their offspring), similar to but not as strict as that of the Hamadryas Baboon ( P. hamadryas ). The rigid herding behavior of male Hamadryas Baboons has not been observed in Guinea Baboon:s. In free-ranging Guinea Baboons, the OMU-based organization is not as obvious. In many cases, subgroups or “parties” contain more than one adult male, and females interact with several males. Several parties seem to form the next higher level of their society—a “gang.” In contrast to other baboons, adult male Guinea Baboons seem to be highly tolerant of each other, they interact affiliatively, and show an elaborate greeting behavior. They have the smallest testes of all the baboons suggesting that sperm competition among males is negligible. Guinea Baboons in Niokola-Koba usually sleep in large trees in gallery forests. In a preliminary population-level genetic study in Niokolo-Koba, overall genetic relationships among group males were similar to those among females, suggesting that males have a similar tendency to stay in their natal group (male philopatry) as do females. In Niokolo-Koba, densities are 2-15 ind/km?.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. The Guinea Baboon is listed as Class B in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. In the past, large numbers were exported for laboratory use, particularly from Senegal. There is reason to believe that Guinea Baboons have undergone a range contraction because of large-scale agricultural expansion, persecution, and hunting, possibly ¢.20-25% in the past 30 years. Their adaptability to a wide variety of habitats has probably enabled them to remain locally common, but outside protected areas their numbers have sharply declined because of bushmeat hunting (Mali, Guinea, and Guinea Bissau) or persecution because of their crop raiding (Senegal). Guinea Baboons occur in several national parks: Kiang West in Gambia, Niokolo-Koba in Senegal, Outamba-Kilimi in Sierra Leone, Badiar and Haut Niger in Guinea, and Bafing in Mali. Niokolo-Koba National Park was classified as a World Heritage Site in Danger by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Oranganization in 2007.

Bibliography. Anderson & McGrew (1984), Balzamo et al. (1973), Bert et al. (1967a, 1967b), Boese (1973, 1975), Booth (1958b), Brito et al. (2010), Brugiére & Magassouba (2009), Byrne (1981), Culot (2003), Dunbar (1988), Dunbar & Nathan (1972), Dutrillaux et al. (1979), Fickenscher (2010), Frost et al. (2003), Galat-Luong & Galat (2003), Galat-Luong et al. (2006), Galat, Galat-Luong & Keita (1999/2000), Galat, Galat-Luong & Nizinski (2009b), Gauthier (1999), Gauthier & Rouliet (1999), Gilleau & Pallaud (1988), Gippoliti & Dell’Omo (2003), Groves (2001), Grubb (2006), Grubb et al. (1998), Grueter & Zinner (2004), Happel (1988), Harding (1984), Hill (1970), Jolly (1993, 1997/1998, 2007), Jolly & Phillips-Conroy (2006), Kingdon (1997), Klapproth (2010), Krebs (2011), Lepoivre & Pallaud (1985), Lucotte (1979), Lucotte & Guillon (1979), Lucotte et al. (1983), Maestripieri, Leoni et al. (2005), Maestripieri, Mayhew et al. (2007), McGrew, Tutin, Baldwin et al. (1978), McGrew, Tutin, Collins & File (1989), Newman et al. (2004), Oates (2011), Pallaud & West (1986), Patzelt et al. (2011), Petit & Thierry (1993), Petit et al. (1997), Sharman (1981), Stueckle et al. (2009), Swedell (2011), Verbruggen (2003), Ziegler et al. (2002), Zinner, Buba et al. (2011), Zinner, Groeneveld, et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.