Papio ursinus (Kerr, 1792)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863229 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFE2-FFE0-FFEB-6DD2FCF8F7A9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Papio ursinus |

| status |

|

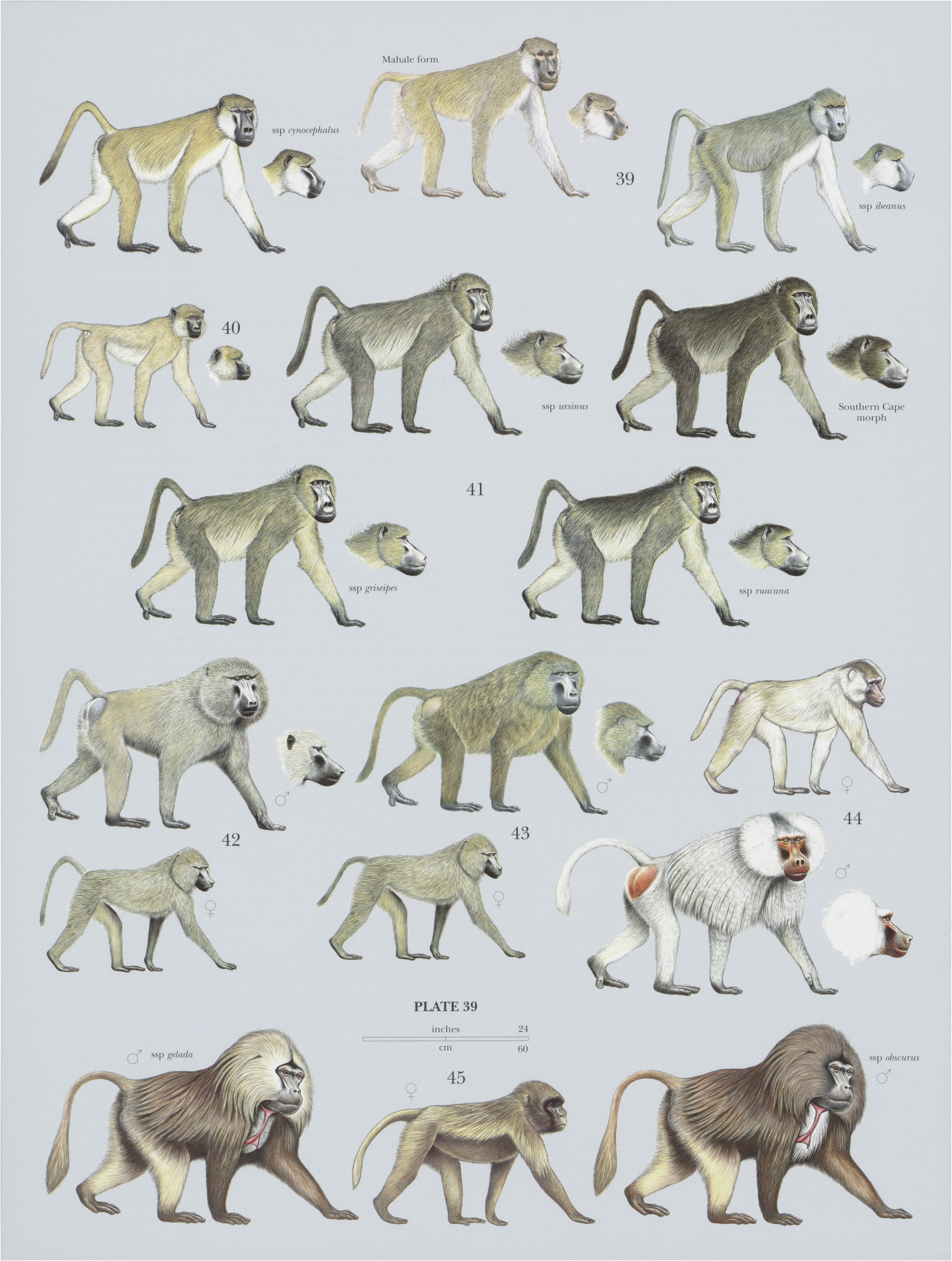

41. View Plate 39: Cercopithecidae

Chacma Baboon

French: Babouin chacma / German: Barenpavian / Spanish: Papion chacma

Other common names: Mountain Baboon; Gray-footed Chacma Baboon (griseipes), Namibian Chacma Baboon (ruacana), Southern Chacma Baboon ( ursinus)

Taxonomy. Simia (Cercopithecus) hamadryas ursinus Kerr, 1792 ,

South Africa, Western Cape Province, Cape of Good Hope.

In respective contact zones in Zambia, the subspecies griseipes hybridizes with P. kindae and P. c. cynocephalus . The exact distributional boundaries of the subspecies and the extent of hybridization are unclear. The southern and northern populations, carrying genetically different mitochondria (most likely Pw. wrsinus and P. u. gniseipes), geographically overlap in the Loskop Dam Nature Reserve, South Africa, in the east and in central Namibia in the west. Although P. ursinus from sites south of the Limpopo carry “griseipes” mitochondria and are quite light in color, they have black hands and feet instead of gray hands and feet as in typical griseipes. A third mitochondrial lineage, most likely representing ruacana, is found in extreme northern Namibia and south-western Angola. Three subspecies recognized.

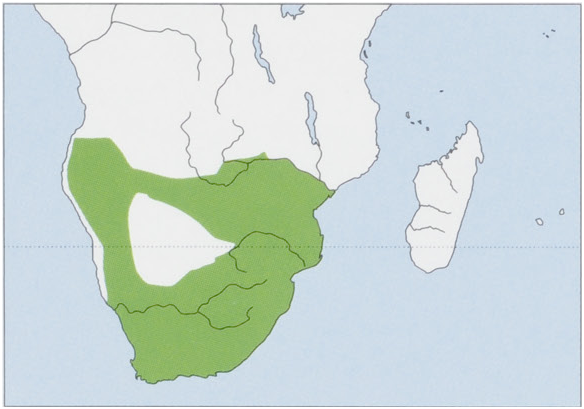

Subspecies and Distribution.

P.u. ruacana Shortridge, 1942 — SW Angola (N along the coast to c¢.11° 30” S) and N Namibia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 68-100 cm (males) and 51-62 cm (females), tail 42— 84 cm (males) and 37-44 cm (females); weight 25-35 kg (males) and 12-20 kg (females). Sexual dimorphism in body weight of the Chacma Baboon is pronounced; female body mass is only 52-60% of male body mass. It is the largest of the baboons. Generally, fur is black to dark brown or gray-buff above, with a lighter, almost naked, underside and pale patches on sides of the muzzle. Cape and Kalahari Chacma Baboons are very dark, almost black, but the “Gray-footed Chacma Baboon” (P. u. griseipes) 1s not darker than the Olive Baboon ( P. anubis ). Adult male Chacma Baboons lack a shoulder mane but have elongated hair tufts along the nape. Facial skin is grayish-black, and both sexes have a set of blackish ischial callosities. Unlike other baboons, the facial part of the skull points downward as well as forward. Nostrils do not protrude beyond the upper lip of the snout. Tail is normally held up and then drops down, “broken,” in an inverted “U.” In the Southern Cape, the coat of the “Southern Chacma Baboon” (P. u. ursinus ) is nearly black, along with black hands, feet, and tail. This color becomes lighter in a cline toward the north-east, but extremities are still black. Gray-footed Chacma Baboons are generally fawn colored, with a grayish tail, hands, and feet. The “Namibian Chacma Baboon” (P. u. ruacana) is a relatively small subspecies, darker than the Gray-footed Chacma Baboon but tending to be especially dark on the back and crown, where blackened tones may contrast with lighter flanks and limbs. Feet are black. Infants are born with black natal coats that change to adult coloration at 3-6 months of age.

Habitat. A range of habitats including all types of woodland, savanna, steppes, Acacia scrub and semi-desert, swamps, seaside cliffs, and montane regions (up to 3000 m above sea level in the Drakensberg Mountains). As in other baboons, the availability of drinking water limits its overall range in arid areas in Namibia, and, for example. in the Karoo and Kalahari deserts. In some areas, Chacma Baboons benefit from human activities, particularly where water has been provided in cattle troughs and irrigation canals. In some habitats, such as in the Namib Desert, habitat choice is also influenced by predation risk. Cliffs, hills or large trees are necessary night-time retreats. Chacma Baboons also use caves as sleeping sites, in particular during cold southern winters.

Food and Feeding. The Chacma Baboon is an opportunistic omnivore, and its diet varies locally. If available, Chacma Baboons feed on fruits, young leaves, flowers, tuberous roots, bulbs, grasses, bark, twigs, sap, mushrooms, lichens, seeds, shoots, buds, aquatic plants, and seashore animals (e.g. crustaceans, mussels, and snails). Other animal prey is also taken, including invertebrates such as insects and larger vertebrates such as lizards, birds, and small mammals. Occasionally, they may take small antelopes and the young of impala (Aepyceros). Crops (maize, tomatoes, citrus, and root crops) and garbage dumps are raided in settled areas. Lambs and small livestock are taken in some ranching areas. They often beg for food from tourists or take food from houses.

Breeding. Births of Chacma Baboons occur throughout the year. The mean length of the menstrual cycle at De Hoop, South Africa,is 39-7 days. In Moremi (Okavango), females have their first infant at six years and nine months of age. The interbirth interval is 22-39 months, but it is longer in the Drakensberg Mountains. The dominant male of the group tries to monopolize access to sexually receptive females. A male and a female form a temporary consortship, and most mating happens during these consort periods. In contrast to Yellow ( P. cynocephalus ) and Olive ( P. anubis ) baboons, a consorting male Chacma Baboon is rarely challenged by other males, and male consort partners do not change often during receptive periods of a female. Males also do not form coalitions to take over a sexually receptive female from the dominant male, as they do in Yellow and Olive baboons. Hence, paternity probability for a particular male Chacma Baboon is higher than in Olive and Yellow baboons, which may be a reason why rates of infanticide are higher in Chacma Baboons than other baboon species. In some populations, more than 30% of the infants are killed by males. Females give copulation calls; they vocalize during or shortly after copulation. These calls are much louder than those of female Hamadryas ( P. hamadryas ) or Guinea (PF. papio ) baboons.

Activity patterns. Chacma Baboons are diurnal and mainly terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Depending on ecological conditions and group sizes, the home range sizes of Chacma Baboons vary substantially (1-37 km?). Average daily movements are 3-6-8-5 km (range 2-13 km). Group size averages 20-80 individuals, but it can be as large as 130 individuals. The ratio of males to females is 1:1-5-10-3. As in Yellow and Olive baboons, the social organization is multimale-multifemale, although Chacma Baboons tend to have smaller groups. Groups are not substructured into one-male units, as they are in Hamadryas Baboons or Geladas ( Theropithecus gelada ). Solitary one-male units of Chacma Baboons, consisting of a few females and a single male, have been observed rarely, but a survey in the Drakensberg Mountains found that such one-male units made up 50% of groups above 2100 m. Females remain in their natal groups and form linear dominance hierarchies. Males also establish a dominance hierarchy that usually regulates access to sexually receptive females. Most males emigrate from their natal groups and attain high rank after joining a new group. Male Chacma Baboons may fight vigorously for a dominant position. Before they start fighting, they often have vocalization contests, running up and down producing their specific loud calls, the “wahoo.” These contests are believed to signal power and stamina to opponents. As in Yellow Baboons, the social network among related females is the most stable social structure. Grooming and other affiliative behavior occur predominantly within these networks. Studies suggest that these tight relationships provide a fitness advantage for females. Females with a tighter network live longer and reproduce more successfully. Females and males may also form bonds outside sexual consortships, called “friendships.” These relationships likely benefit a female via protection for herself and her offspring against sexual harassment and infanticide by other males. The male benefits because it may protect its own offspring or it may invest in future sexual relationship with the respective females. Densities of Chacma Baboons can range from one to more than 24 ind/km? in some protected areas.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List, including all three subspecies (ruacana under P. ursinus ursinus ). The Chacma Baboon is widespread and abundant, and there are evidently no major threats causing a range-wide decline. Outside of protected areas, however,it has been extirpated from large parts of its former distribution, mainly because of agricultural and infrastructural development. Baboons are shot and trapped as crop raiders. Chacma Baboons occur in many protected areas. Southern Chacma Baboons occur in Table Mountain National Park, Namaqua National Park, Mountain Zebra National Park, Augrabies Falls National Park, De Hoop Nature Reserve, Goegab Nature Reserve, Cape nature reserves, Giant’s Castle Game Reserve in South Africa and Namib-Naukluft and Fish River Canyon national parks in Namibia. Gray-footed Chacma Baboons occur in Etosha and Waterberg Plateau national parks in Namibia; Chobe National Park and Moremi Game Reserve in Botswana; Gorongosa National Park and Pomene Game Reserve in Mozambique; Lower Zambezi, Kafue, and Lochinvar national parks in Zambia; and Victoria Falls, Chimanimani, Hwange, and Mana Pools national parks in Zimbabwe. Namibian Chacma Baboons occur in Iona National Park and Namibe Reserve in Angola. It is unclear if baboons in Pilanesberg Game Reserve, Blyde River Canyon Nature Reserve, Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Game Reserve, Ithala Game Reserve, and Kruger National Park (South Africa) are Gray-footed Chacma Baboons.

Bibliography. Anderson (1981a, 1981b, 1983, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1992), Barrett & Henzi (1997, 1998), Barrett et al. (2004), Barton et al. (1996), Beehner et al. (2005), Bergman et al. (2006), Bidner (2009), Bielert (1986), Bielert & Girolami (1986), Bielert & van der Walt (1982), Bigalke & van Hensbergen (1990), Bolwig (1959), Booth & Freedman (1970), Brain (1988, 1990, 1991, 1992), Brain & Mitchell (1999), Brown et al. (2006), Bulger (1993), Bulger & Hamilton (1987), Buskirk et al. (1974), Busse (1980, 1984), Busse & Hamilton (1981), Byrne, Whiten & Henzi (1987), Byrne, Whiten, Henzi & McCulloch (1993), Cambefort (1981), Cheney et al. (2004), Clarke et al. (2008), Codron et al. (2006), Cowlishaw (1997a, 1997b), Davies & Cowlishaw (1996), Davidge (1978a, 1978b), van Doorn et al. (2010), Dunham (1994), Engh et al. (2006), Ey et al. (2007), Fischer, Hammerschmidt et al. (2001), Fischer, Kitchen et al. (2004), Frost et al. (2003), Gaynor (1994), Gillman & Gilbert (1946), Girolami & Bielert (1987), Groves (2001), Grubb (2006), Hall (1960, 1961, 1962a, 1962b, 1963), Hamilton & Arrowood (1978), Hamilton & Bulger (1990, 1992, 1993), Hamilton & Busse (1982), Hamilton & Tilson (1982, 1985), Hamilton, Buskirk & Buskirk (1975, 1976, 1978), Hamilton, Busse & Smith (1982), Henzi & Lycett (1995), Henzi, Brown et al. (2011), Henzi, Byrne & Whiten (1992), Henzi, Dyson & Deenik (1990), Henzi, Lycett & Weingrill (1998), Henzi, Weingrill & Barrett (1999), Henzi, Lycett, Weingrill, Byrne & Whiten (1997), Henzi, Lycett, Weingrill & Piper (2000), Hill, R.A. (2006a, 2006b), Hill, R.A., Barrett et al. (2003), Hill, R.A., Weingrill et al. (2004), Hill, W.C.O. (1970), Hoffman & O'Riain (2011), Huchard & Cowlishaw (2011), Huchard et al. (2010), Johnson (2003), Jolly (1993, 1997/1998, 2007), Jolly et al. (2011), Katsvanga, Jimu, Mupangwa & Zinner (2009), Katsvanga, Jimu, Zinner & Mupangwa (2009), Katsvanga, Mudyiwa & Gwenzi (2006), Keller et al. (2010), King & Cowlishaw (2009), Kingdon (1997), Kitchen, Beehner et al. (2009), Kitchen, Cheney & Seyfarth (2004), Kitchen, Seyfarth et al. (2003), Kok & Nel (1996), Krebs (2011), Lycett, Henzi & Barrett (1998), Lycett, Weingrill & Henzi (1999), Lynch (1983, 1989, 1994), Machado (1969), Marais et al. (2006), McGrew et al. (2003), Melnick & Pearl (1987), Moscovice et al. (2009), Newman et al. (2004), Noser & Byrne (2007), O'Connell & Cowlishaw (1994), Palombit (2009), Palombit et al. (2000), Pebsworth et al. (2011), Rhine et al. (1985), Ron (1996), Ron, Henzi & Motro (1996), Ron, Henzi, Whitehead & Gaynor (1990), Saayman (1970, 1971a, 1971b, 1971c), Segal (2008), Shortridge (1934, 1942), Sithaldeen et al. (2009), Smith (1986), Stoltz (1972), Stoltz & Keith (1973), Stoltz & Saayman (1970), Swedell (2011), Tarara (1987), Viljoen (1982), Watson (1985), Weingrill (2000), Weingrill, Lycett, Barrett et al. (2003), Weingrill, Lycett & Henzi (2000), Whiten et al. (1987), Zinner, Buba et al. (2011), Zinner, Groeneveld et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.