Rungwecebus kipunji (Ehardt et al., 2005)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863221 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFDE-FFE4-FAFE-615BF92BF70E |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Rungwecebus kipunji |

| status |

|

38. View On

Kipunji

Rungwecebus kipunji View in CoL

French: Kipunji / German: Kipunji-Affe / Spanish: Kipunji

Taxonomy. Lophocebus kipunji Ehardt et al. 2005 View in CoL ,

Rungwe-Livingstone (09° 07° S to 09° 11° S and 33° 40° E to 33° 55 FE), Southern Highlands, Tanzania.

R. kipunji was originally allocated to the genus Lophocebus based on its non-contrasting black eyelids and arboreal nature, but later placed in a new monotypic genus Rungwecebus on the basis of molecular and morphological data. Rungwecebus was initially questioned, but additional molecular evidence and morphometric analyses support its phylogenetic position and taxonomic status. Monotypic.

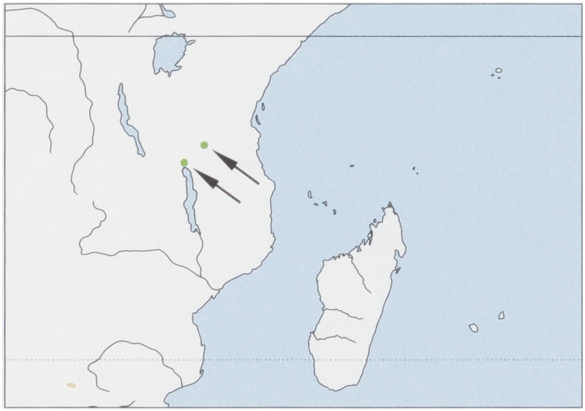

Distribution. Endemic to S Tanzania in just two isolated sites, the Southern Highlands and the Udzungwa Mts. View Figure

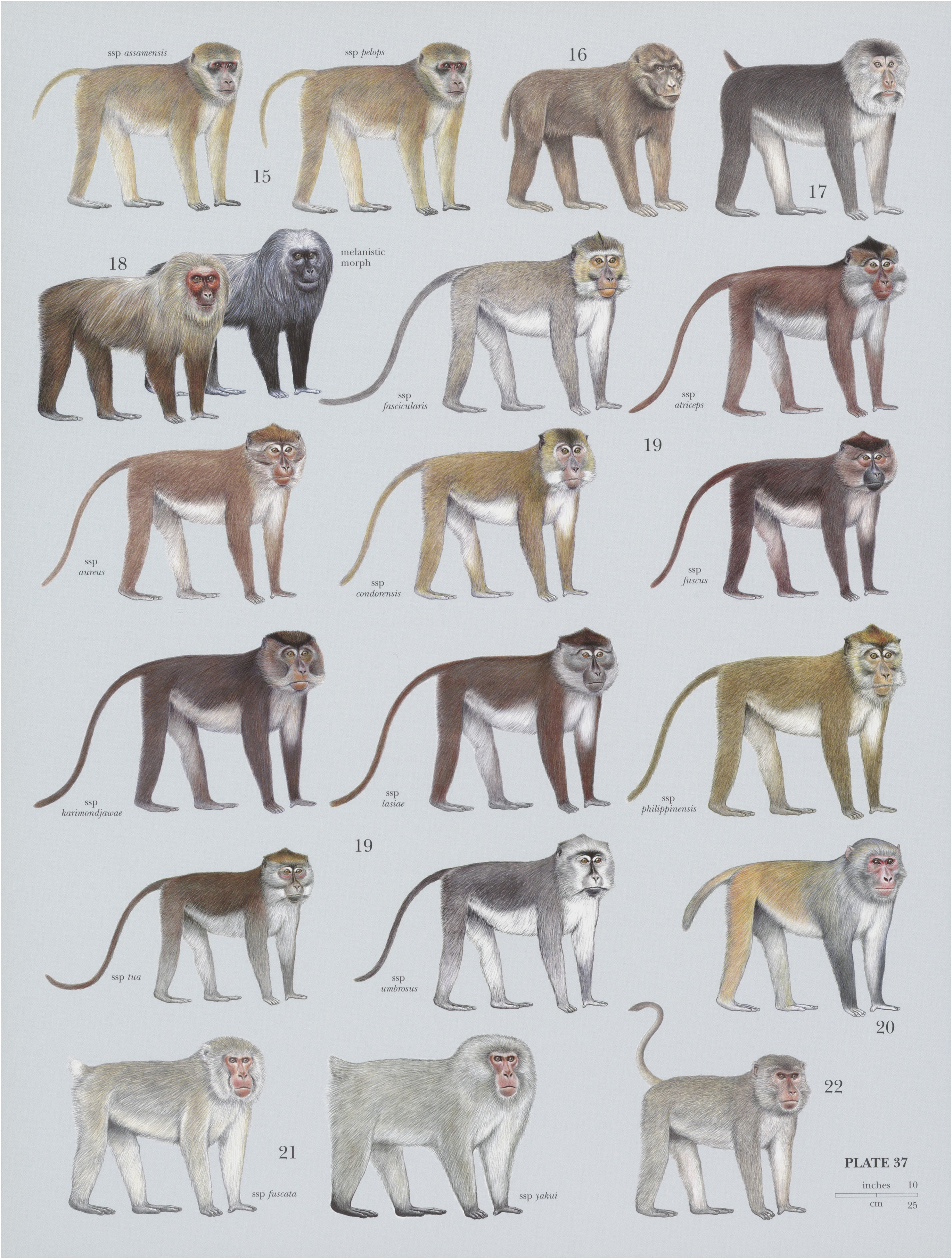

Descriptive notes. No exact adult measurements are available, but the head-body length is estimated at ¢.85-90 cm,the tail a little longer; weight c¢.10-15 kg. The Kipunji is a mostly brown, medium-sized, long-tailed, arboreal monkey. Sexes are similar in color, and adult females are estimated to be 90% the weight of adult males. Facial skin, including eyelids, is black. Muzzle is bare, relatively elongated, and black. Suborbital fossa is pronounced. Eyes are brown. Cheek-whiskers are long, extending laterally and curving downward. Crown has a prominent, long, broad, and erect crest of dark grayish-brown hair. Shoulder mane (mantle or cape) of adult males, variable in color and length, typically has long, straight, cinnamon-brown hairs. Lower dorsum is light to medium grayish-brown. Forelimbs are a dark grayish-brown. Upper hindlimbs are dark rufous-brown, and lower hindlimbs are cinnamon. Hands and feet are black. Ventrum is off-white. There is a patch on the upper chest that is close to cinnamon. Individual hairs are long and straight, without banding or speckling. Ischial callosities are pink and fused in males and not fused in females. Tail is dusky-brown over the proximal half and off-white with interspersed darker hairs over the distal half. Its pelage is smooth, not shaggy or lax. Tail is carried loosely and parallel to, or below, the plane of the back, curving downward to the level of the feet during locomotion. It is not held arched over the back when standing, nor held vertically, except as a semi-prehensile support. Infants are less hirsute with a reddish tinge to their pelage.

Habitat. Degraded montane and upper montane forest at 1500-2450 m above sea level in Rungwe-Kitulo to pristine submontane forest at 1300-1750 m in Ndundulu. In Rungwe-Kitulo, the canopy is often broken at 10-30 m with emergents as high as 35 m. Kipunjis prefer steep-sided gullies and valley edges. Ridges and open areas are usually avoided. Numbers of Albizia gummifera ( Fabaceae ), Casearia battiscombei ( Salicaceae ), Entandrophragma sp. (Meliaceae) , Macaranga kilimandscharica ( Euphorbiaceae ), Ocotea usambarensis ( Lauraceae ), Olea capensis (Oleaceae) , Parinari excelsa (Chrysobalanaceae) , Podocarpus latifolius ( Podocarpaceae ), and Prunus africana ( Rosaceae ) have been greatly reduced by logging. Thick undergrowth is typical, with tree ferns Cyathea manniana ( Cyatheaceae ), wild bananas Ensete ventricosum ( Musaceae ), and large stands of bamboo Sinarundinaria alpina ( Poaceae ), common in the south and south-east of Mount Rungwe and in the north-west of Livingstone. Kipunjis rarely frequent bamboo, and they leave the forest only to raid nearby crops, especially in February—April. In areas inhabited by the Kipunji , annual rainfall is ¢.1850-2500 mm. Mean annual rainfall from 1968 to 2008 was 2133 mm. The wet season is in November—May, and the dry (colder) season is in June-October. In Ndundulu, the primary forest, dominated by P. excelsa , is mostly undisturbed and its canopy unbroken, reaching heights of 40-50 m.

Food and Feeding. The Kipunji is omnivorous. During 9498 hours of observation of 34 groups in the Southern Highlands, 122 food plants from 60 families were recorded in the diet (64 tree species, 30 herbs, nine climbers, seven shrubs, six lianas, three grasses, and three ferns). The diet comprises mature leaves (22%), unripe fruits (14%), ripe fruits (13%), young leaves (12%), bark (11%), stalks (9%), flowers (9%), pith (7%), insects (2%), and seed pods, rhizomes, shoots, tubers, epiphytes, ground herbs, climbers, moss, fungi and lichen (2%). Kipunji ate soil on two occasions. They also raid maize, bean, pea, sweet potato, and banana crops and granaries if close to the forest edge. The most frequently eaten plant is Macaranga capensis (Euphorbiaceae) . Other commonly eaten plants include Ilex mitis (Aquifoliaceae) , Psydrax parviflora ( Rubiaceae ), Chrysophyllum gorungosanum ( Sapotaceae ), Bersama abyssinica (Melianthaceae) , Myrianthus holstii ( Cecropiaceae ), Tabernaemontana stapfiana and Landolphia buchananii (both Apocynaceae ), Urera hypselodendron ( Urticaceae ), Tarenna pavettoides and Multidentia crassa (both Rubiaceae ), Cassipourea gummiflua ( Rhizophoraceae ), Allophylus abyssinicus (Sapindaceae) , Parinari excelsa , Entandrophragma excelsum ( Meliaceae ), Ficus thonningii ( Moraceae ) and Polyscias fulva ( Araliaceae ). They are able to open large, hard fruits and break apart dead wood in search of grubs. The Kipunji appears to be more folivorous during the dry season and more frugivorous during the wet season. Most foraging occurs in the early morning and late afternoon.

Breeding. Little is known about breeding in the Kipunji . In Rungwe-Kitulo, Kipunjis were seen mating on four occasions, all in late September. One pair moved ¢.200 m from the main group, copulated twice in ten minutes and again 45 minutes after that. Copulations lasted 3-7 seconds. Infants are carried beneath the female. Instances of “kidnapping” are accompanied by loud screams and chasing. The female’s genitals swell during the periovulatory period. Single offspring are born; twins have not been recorded. Infants are born throughout the year, and there is no evidence of a birth season or birth peak. The gestation period is 6-7 months.

Activity patterns. Kipunjis are diurnal and arboreal, foraging and traveling mainly at 10 m or more above the ground. It occasionally feeds on the forest floor, particularly in the dry season. The Kipunji also goes to the ground to cross degraded forest patches and to avoid intragroup conflict and predators. Kipunjis are tolerant of low temperatures; in parts of Rungwe-Kitulo, temperatures can drop to -3°C in June-August. They sleep high up, usually above 20 m, in branches oftrees such as B. abyssinica , M. holstii, Maesa lanceolata ( Myrsinaceae ), and Syzygium guineense ( Myrtaceae ). They usually rest for 30-60 minutes in the middle of the day. They are most active at 08:00-11:30 h and 15:00-18:00 h.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Groups of Kipunjis in Rungwe-Kitulo travel a mean of 1-3 km/day (range 0-99-17, SE = 0-15 km, n = 235 days), and group members usually remain within 300 m of each other, except when disturbed. Mean home range in Mount Rungwe is 306 ha (116-430 ha, SE = 67 ha, n = 4 groups). The Kipunji is social and notterritorial. Groups comprise several adult males and several adult females. Group sizes are 20-39 individuals in Rungwe-Kitulo and 15-25 in Ndundulu. In 34 groups that were closely monitored in Rungwe-Kitulo, there were up to five clinging infants per group. There is no evidence ofsolitary individuals. In Rungwe-Kitulo, groups of Kipunjis form polyspecific associations with the Angolan Colobus ( Colobus angolensis ) and Sykes’s Monkey ( Cercopithecus albogularis moloneyi), especially in early morning and late afternoon. The three species often sleep in neighboring trees. Groups of Kipunji at Ndundulu form polyspecific associations with Angolan Colobus , Sykes’s Monkeys, and Udzungwa Red Colobus ( Piliocolobus gordonorum ). Grooming is observed most often in the early afternoon. Receptive females are often groomed by young males, although female—female, female-male, and adult—juvenile grooming are also observed. Intergroup territorial displays occur when ranges overlap. Disputes are often highly vocal in Rungwe-Kitulo, usually involving adult males, but sometimes females and juveniles also call. No intergroup physical contact was observed in over 772 hours of direct observation. In Rungwe-Kitulo, adult males emit a distinctive, loud, low-pitched “honk-bark,” most evident when conspecific groups meet and when threatened or disturbed. Adult females also give this call but less often than males. Honk-barks can be heard by the human ear up to 1 km away and are used as a groupspacing mechanism. The honk-bark is qualitatively and quantifiably different from the “whoop-gobble” of species of crested mangabeys ( Lophocebus ) and has some structural congruence to the “roar-grunt” of baboons ( Papio ). At least ten other call types of Kipunjis have been identified, including contact grunts. High-pitched, sharp screams are given in alarm when crowned hawk-eagles (Stephanoatus coronatus) are seen and during intragroup agonistic encounters.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Kipunji is known from just two sites of largely non-forested land separated by ¢.350 km. One fragmented population occurs at 1750-2450 m above sea level in only 42 km* of Rungwe-Kitulo Forest in the Southern Highlands. This forest includes Mount Rungwe Nature Reserve of 150 km” and the Livingstone Forest of 191 km? (in Kitulo National Park of 412 km?). Mount Rungwe Nature Reserve and Livingstone Forest are connected by the Bujingijila Corridor, a narrow (less than 2 km wide) strip of degraded forest. The Kipunji inhabits the wetter forest of southern Mount Rungwe, and isolated groups are scattered in the northern and southern areas of Livingstone Forest. The extent of their occurrence in Mount Rungwe and Livingstone is 23-7 km* and 18-3 km?, respectively. Anecdotal evidence points to the historic presence of Kipunjis in other forests of the Southern Highlands. The second population of the Kipunji occurs at elevations of 1300-1750 m in the Vikongwa Valley, Ndundulu Forest, in the Kilombero Nature Reserve in the Udzungwa Mountains. The known extent of occurrence in the Ndundulu Forest is at least 5-3 km?, but is likely to be much larger. The total population of the Kipunji is estimated to be 1117 animals in 38 groups. Of these, 1042 individuals occur in Rungwe-Kitulo in 34 groups, and there are only 75 individuals in Ndundulu in four groups. Kipunjis are Africa’s most threatened monkey and one of the world’s most threatened primates. Threats to Kipunjis are considerable. The Rungwe-Kitulo forests are severely degraded; logging, charcoalmaking, illegal hunting, and unmanaged resource extraction are common. The narrow Bujingijila Corridor linking Mount Rungwe to Livingstone Forest and corridors joining the northern and southern sections of Livingstone have been encroached upon and degraded by farmers. Without immediate conservation intervention, these forests will be fragmented, resulting in the isolation of Kipunji subpopulations, some of which are unlikely to be viable over the long term. Protecting these corridors is of the highest priority for the conservation of the Kipunji . It is hunted by local people, especially on farms. Conflicts with local famers become more common as forest disturbance and loss increase. Mount Rungwe was raised to the status of a Nature Reserve in 2009, but it remains largely unmanaged. The smaller population of Kipunjis in Livingstone Forest is within Kitulo National Park, but swift and effective conservation action 1s needed in both areas. Although Ndundulu Forest is in excellent condition, and largely undisturbed, Kipunjis are present in low numbers, and reasons for this are unclear. Kilombero Nature Reserve was established in 2007, incorporating Ndundulu, but as with Mount Rungwe, there is as yetlittle conservation management. The Kipunji is serving as a “flagship” genus and species for the conservation of the Southern Highlands and Udzungwa Mountains. Their presence at both sites demonstrates that the Southern Highlands and Eastern Arcs were linked and are zoologically even more aligned than had previously been thought.

Bibliography. Bracebridge et al. (2011), Davenport (2005, 2006, 2009), Davenport & Jones (2008), Davenport, De Luca, Bracebridge et al. (2010), Davenport, De Luca, Jones et al. (2008), Davenport, Mpunga, et al. (2009), Davenport, Stanley et al. (2006), De Luca et al. (2009), Gilbert et al. (2010), Jones et al. (2005), Olson et al. (2008), Roberts et al. (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Rungwecebus kipunji

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Lophocebus kipunji

| Ehardt et al. 2005 |