Mandrillus sphinx (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863203 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFDA-FFD8-FFEB-6EAAFA9EFD83 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Mandrillus sphinx |

| status |

|

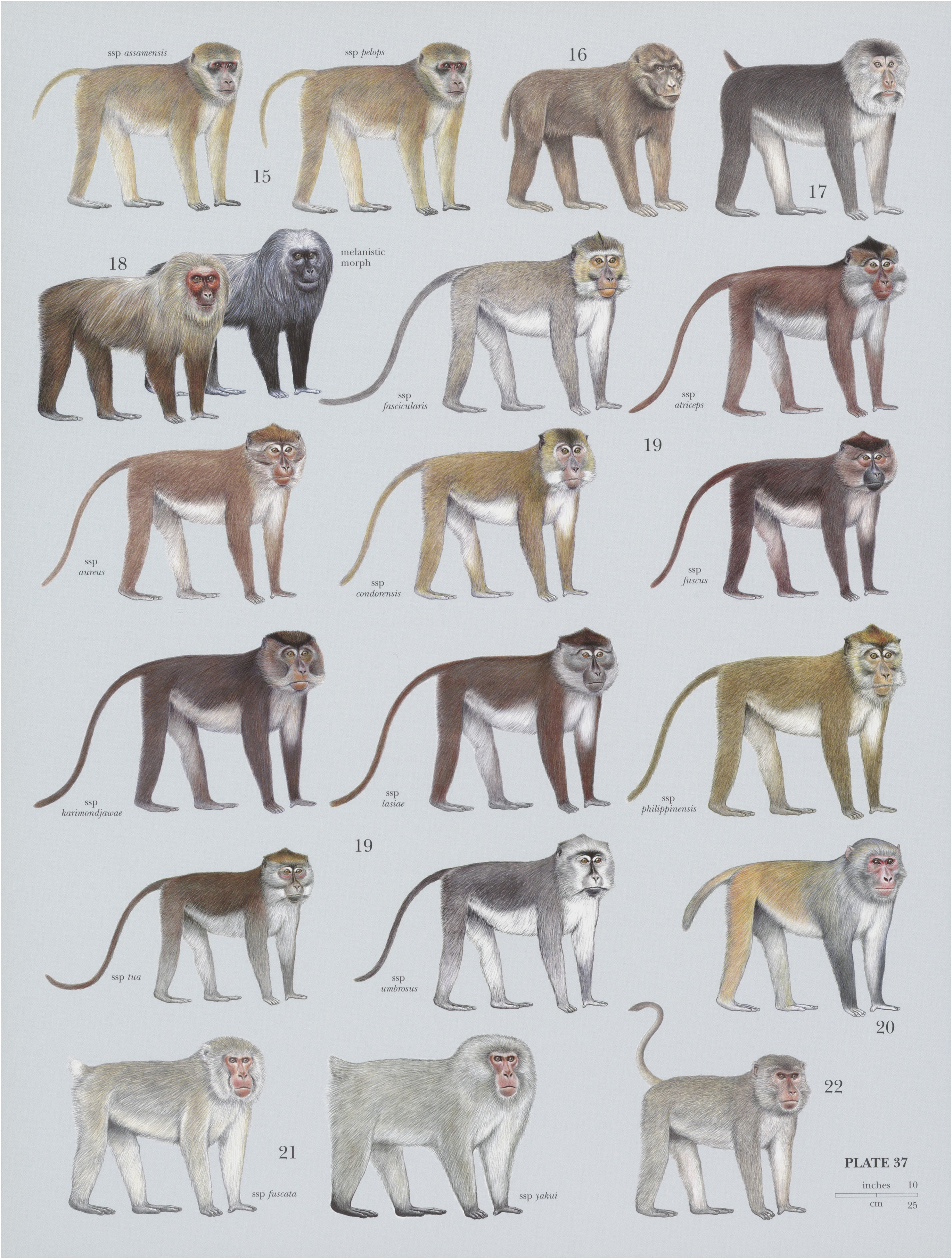

30. View On

Mandrill

French: Mandrill / German: Mandrill / Spanish: Mandril

Taxonomy. Simia sphinx Linnaeus, 1758 ,

Borneo. Restricted by E. Delson and P. Napier in 1976 to “Cameroon, Bitye, Dja River.”

Molecular studies suggest that there are perhaps two distinct populations of M. sphinx . A study by P. T. Telfer and colleagues in 2003 indicated that the Ogooué River in Gabon bisects their distribution, separating them into two distinct populations: Cameroon and northern Gabon, and southern Gabon. Monotypic.

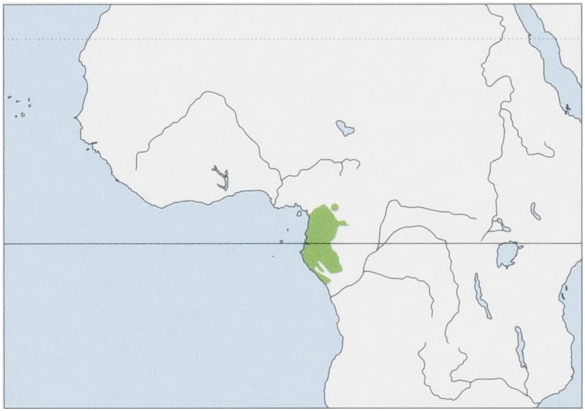

Distribution. W Central Africa, from S Cameroon (S of the Sanaga River) to mainland Equatorial Guinea, W Gabon (Ivindo and Ogooué rivers limit its distribution to the E), and SW Republic of the Congo (S to the Kouilou River and down to the Congo River). It is not known to occur east of the Dja River in Cameroon, and it does not occur in the forests of SE Cameroon. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 62-110 cm (males) and 55-67 cm (females), tail 7-10 cm (males) and 5-9 cm (females); weight 18-33 kg (males) 11-13 kg (females). Mandrills and Drills (M. leucophaeus ) are the largest living monkeys and certainly among the most physically impressive. Fur is long and thick and grayish-brown dorsally, with a sulphuryellow underside. Tail is short and invariably held erect. Sexes differ remarkably in size; female body mass is 36:5% of male body mass. Males have a proportionately bigger head than females, a heavy mane, massive muzzle, and formidable upper canines. Besides their enormous build, Mandrills have remarkable coloration, best exemplified in the deeply ridged, brilliantly hued snout and equally luminous rump of the dominant male. The bridge of the nose and lips are a rich, lacquered scarlet, while sides of the nose are pale blue with traces of purple in the grooves. There are fringes of whitish orange fur on cheeks and white behind the ears and a small crest atop the head. When a male has attained alpha status, he undergoes physical changes and becomes more brightly colored and has a higher testosterone level. With a loss ofstatus, the reverse changes occur. Both sexes sport a yellowish-orange beard. The rump also distinguishes mature males; it is adorned with a broad patch of blue, red, and violet skin, set against prominent reddish genitalia. Mandrills, like Drills, have a sternal gland. Both sexes use this gland to scent-mark by rubbing their chests on a substrate or object. The functions of scent marking are not clear. It may help reinforce dominance status, it may play a role in mate choice because odors can encode information on sex, rank, and genotype, or it may be used to orient within the home range.

Habitat. Moist evergreen rainforest stretching 100-300 km inland from the Atlantic coast, semi-montane forest, and dense secondary forest. Mandrills are known to occur in forest fragments in savanna and use plantations, particularly during the dry season. There are two rainy and two dry seasons of roughly equal durations in the distribution of the Mandrill; the timing of these seasons differs north and south of the Equator.

Food and Feeding. Mandrills are omnivorous, and their diets are diverse, including fruits, buds, leaves, roots, fungus, seeds, and animal prey (insects, crabs, fish, amphibians, lizards, birds, and small mammals up to the size of duikers). They prefer fruits when they are available. In their primary forest habitat, fruiting of trees and lianas is irregular, leading to periodic fruit shortages. When this occurs, Mandrills are highly reliant on having abundant herbaceous plants to eat. When food is scarce (during and at the end of the dry season), they also raid crops. They forage mainly less than 5 m off the ground. Males spend most of their time on the ground, but females and young will forage in trees.

Breeding. There is no specific information available for this species in the wild, but in captivity or semi-captivity, female Mandrills have, on average, a 33day menstrual cycle. Onset of the receptive period is signaled by genital swelling and reddening that reaches its peak around ovulation. The privilege of mating appears to be mostly restricted to alpha males. There is usually no set breeding season, but births are most frequent in December—April. Usually a single young is born after a mean interbirth interval of less than two years. The gestation period lasts 179-182 days. Infants have a pinkish face, silvery gray pelage, white hair on limbs, and a black cap. Juvenile pelage is similar to adults, and they have a dull blue snout and a buffy beard—characteristics that most females retain for life. Adult female Mandrills can be quite pink in the face, but not as much as the males. Females are sexually mature at 4-5 years old, and males at 5-7 years old. Individuals have been known to live for more than 45 years in captivity.

Activity patterns. Mandrills are diurnal and mainly terrestrial.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The home ranges of Mandrills can be 30-50 km? and groups travel up to 15 km/day when foraging. The social organization of Mandrills has historically been unclear, with contradictory observations because they live in dense rainforests and are difficult to follow and observe. Most data have been derived from a semi-free-ranging colony of Mandrills in Gabon, where stable social groups consist of several adult males and females and their offspring. Early reports of wild Mandrills, based on only a few observations, suggested a multilevel social structure similar to Hamadryas Baboons ( Papio hamadryas ) and Geladas ( Theropithecus gelada ), with units of one male and several females as the basal social grouping. Nevertheless, more recent field studies have provided a different picture. Mandrills aggregate into extremely large groups of up to several hundred individuals, termed “hordes.” These large groups seem to remain cohesive and stable (e.g. Lopé National Park, Gabon), but they may split up into smaller groups temporarily. Most unusual for other species in the tribe Papionini , adult male Mandrills at Lopé reside in these large groups only during the mating season and are otherwise solitary.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Mandrill is listed as Class B in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. It is threatened by habitat loss and hunting, and it is sometimes regarded as a pest and killed. Total population size is unknown, but it has undoubtedly declined in recent years. Mandrills occur in 14 protected areas: Campo Ma’an National Park in Cameroon; Monte Alen National Park in Equatorial Guinea; Minkebé, Crystal Mountain, Lopé, Moukalaba-Doudau, Waka, Mayumba, Ivindo, and Birougou national parks, Wonga-Wongue Presidential Reserve, L.ékédi Sanctuary, and Mont Iboundji Sanctuary in Gabon; and Conkouati-Douli National Park in the Republic of the Congo. Several of these need immediate protection, both legal and practical, against logging and hunting.

Bibliography. Abernethy & White (2013), Abernethy et al. (2002), Bettinger et al. (1995), Caldecott et al. (1996), Carman (1979), Chang et al. (1999), Charpentier, Peignot et al. (2005), Charpentier, Setchell et al. (2006), Delson & Napier (1976), Dixson et al. (1993), Feistner (1991, 1992), Feistner et al. (1992), Frost et al. (2003), Groves (2001), Grubb (1973), Harrison (1988b), Hill (1970), Hoshino (1985), Hoshino et al. (1984), Jolly (2007), Jouventin (1975a, 1975b), Kingdon (1997), Krebs (2011), Kudo (1987), Kudo & Mitani (1985), Lahm (1985, 1986), Littlewood & Smith (1979), Mellen et al. (1981), Norris (1988), Rogers etal. (1996), Sabater Pi (1972), Setchell (2003, 2005), Setchell & Dixson (2001a, 2001b, 2001¢, 2002), Setchell & Wickings (2004a, 2004b, 2005), Setchell, Charpentier & Wickings (2005), Setchell, Lee & Wickings (2002), Setchell, Lee, Wickings & Dixson (2001), Swedell (2011), Telfer et al. (2003), White (2007), White et al. (2010), Wickings & Dixson (1992a, 1992b, 1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Cercopithecinae |

|

Genus |

Mandrillus sphinx

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Simia sphinx

| Linnaeus 1758 |