Macaca radiata (E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863165 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFCA-FFC8-FAFF-6369F89CF582 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca radiata |

| status |

|

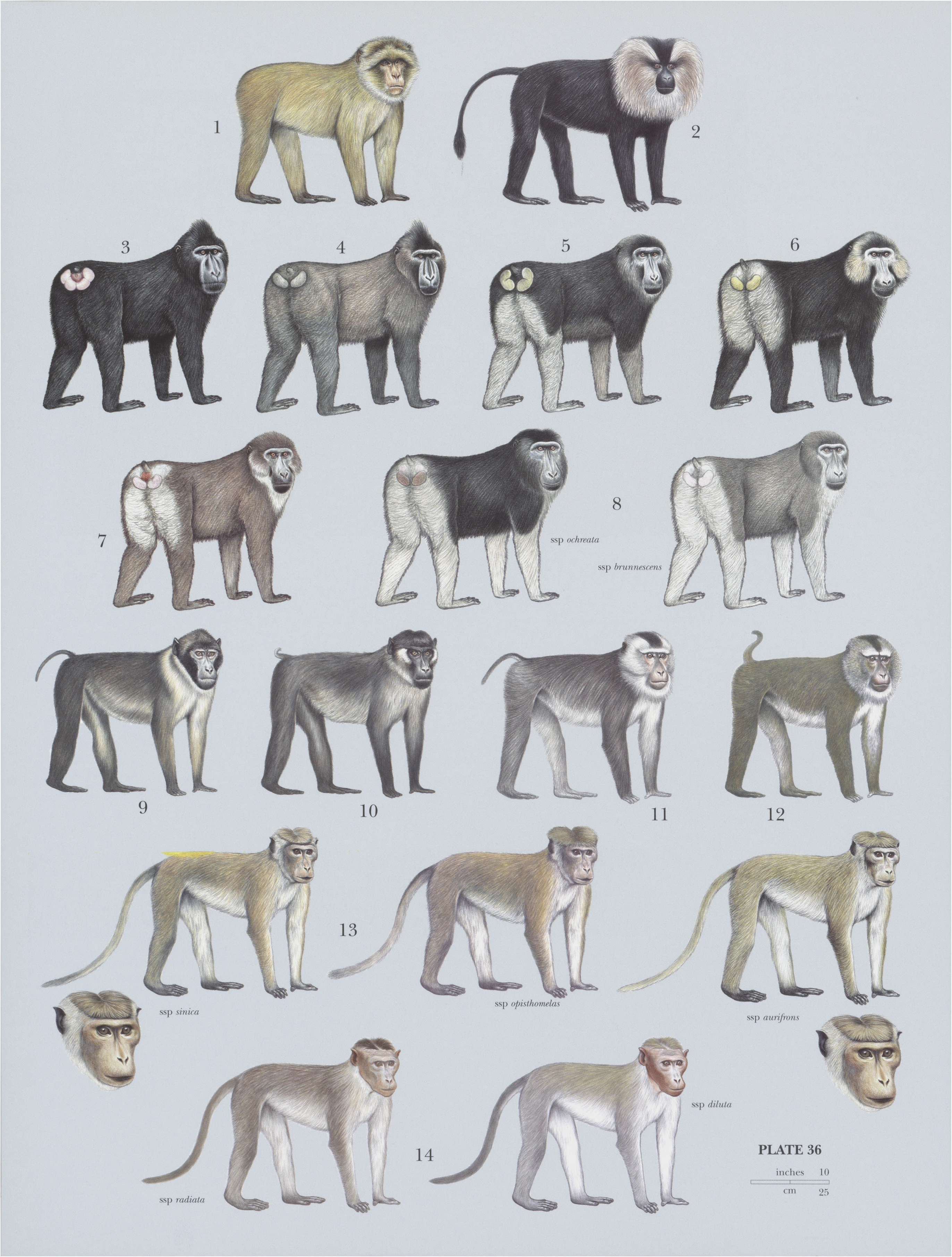

14. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Bonnet Macaque

French: Macaque a bonnet / German: Indien-Hutaffe / Spanish: Macaco de Madras

Other common names: Dark-bellied Bonnet Macaque (radiata), Light-bellied / Pale-bellied Bonnet Macaque (diluta)

Taxonomy. Cercocebus radiatus E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812 ,

India.

M. radiata is a member of the sinica species group of macaques, including M. sinica, M. assamensis , M. thibetana and M. arctoides . It is sympatric with M. silenus in the western part of its distribution. Albinism has been reported. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

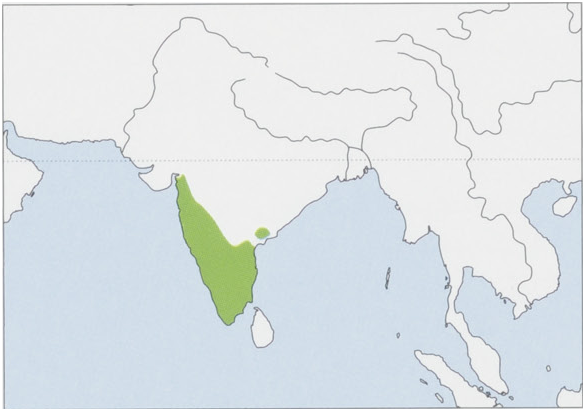

M. r. diluta Pocock, 1931 — SE India (states of Kerala & Tamil Nadu), from the S tip and the SE coast, N to Kambam at the SW foot of the Palni Hills and Puducherry (= Pondicherry) in the E coast. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 51.5-60 cm (males) and 34.5-52.5 cm (females), tail 51-69 cm (males) and 48-63.5 cm (females); weight 5.4-11.6 kg (males) and 2.9-5.5 kg (females). Head-body length of adult males average c.15% greater than those of adult females, and weights of adult males average c.75% greater than those of adult females. The Bonnet Macaqueis a lightly built, rather long-tailed species. The coat is gray-brown to golden-agouti-brown above (becoming duller posteriorly), with slightly paler limbs and a darker dorsal surface of the tail. Underside is buffy or whitish and sparsely haired, with skin showing through. The head has a hatlike crown of hairs radiating from a central whorl to form a circular cap, with posterior hairs longer than anterior hairs and with short forehead hairs parted along the midline. This “bonnet” effect is further accentuated by a high, somewhat balding forehead. Face and ears are bare, with skin of adults being brown to pinkish or bright scarlet in some females. Tail is 88-136% of head-body length. The “Dark-bellied Bonnet Macaque” (M. r. radiata ) is dull gray-brown above with yellow tones, a dark median stripe posteriorly, and ocher-gray limbs. Its crown is grayish brown, with hairs on the cap often black-tipped. Ventral skin is dark bluish-gray. In the “Light-bellied Bonnet Macaque” ( M. r. diluta ), the upper bodyis bright yellow or golden-brown (slightly duller posteriorly), with pale gray-brown limbs. Crown is pale yellowish-brown. Ventral skin is whitish and largely lacks pigment, hence the name light-bellied macaque.

Habitat. Predominantly in lowland, wet evergreen, dry deciduous forests and bamboo up to an elevation of 2100 m and usually near forest edges and along rivers. Bonnet Macaques are commensal with humans and forest dwelling. They have a high tolerance to anthropogenic disturbance, flourishing in urban areas, railway yards, temple compounds, villages, alongside roads (where there are trees nearby), plantations, and farmland. In larger numbers in urban areas, they are considered pests. They are able to live in cultivated areasif they have a few large trees to live in, most notably favoring fig trees such as the banyan tree ( Ficus benghalensis, Moraceae ) and F benjamina. While Dark-bellied Bonnet Macaques are wide ranging and a commensal, the Light-bellied Bonnet Macaque has a restricted distribution, is forest dwelling, and not as abundant. They spend c.30% of their time on the ground as commensals with humans, and only c.10% in their natural habitats, the tall forests.

Food and Feeding. The diet of the Bonnet Macaques is eclectic and includesripe fruits, seeds, flowers, shoots, young and mature leaves, pith, and animals (insects, spiders, frogs and lizards, and bird eggs). As is typical of macaques, Bonnet Macaquesfill their cheek pouches with food to chew and swallow it later. Fruits are a ready source of energy, and they are known to feed on mangoes, lantana, and wild figs. They also extract other nutritional supplements from other plant parts such as calcium from mature leaves and protein from young leaves. Preferred flowers are from Cullenia exarillata ( Malvaceae ), Knema attenuata (Myristicaceae) , Fahrenheitia zeylanica ( Euphorbiaceae ), Loranthus (Loranthaceae) , and Acacia auriculiformis ( Fabaceae ). Bonnet Macaques are also known to feed on leaves and buds of Xylopia parvifolia (Annonaceae) , Mesua ferrea ( Calophyllaceae ), Diospyros buxifolia (Ebeneceae), and Ochlandra (Poaceae) . Their diet consists of 70-1% fruits, 12-:8% flowers, 10-6% leaves, 4-2% leaf buds, and 2-2% seeds. To compensate for the lack of protein in their predominantly fibrous diet, they feed on insects. On occasion, they raid crops such as peanuts, potatoes, beans, carrots, radishes, squash, rice, peas, grains, cauliflowers, coffee, and coconuts. In urban areas, where they generally experience food shortage, they raid garbage dumps and home gardens.

Breeding. The menstrual cycle of the Bonnet Macaque is ¢.28 days (mean 27-8 days), and it is marked by a reddening of the perineum. Bonnet Macaques are strongly seasonal breeders, with most mating occurring in July-September and most births in February-April. Subordinate males are not excluded from mating, and there is no evident consort behavior, but dominant males copulate most and will sometimes attack subordinate males caught in the act. Malesinitiate and solicit mating, and pairs leave the group temporarily to mate, as far as 500 m away. Pheromonal cues indicate when a female is receptive. Females terminate copulation as and when they want. Groups with just one male can be susceptible to what is termed a “male influx,” during their brief mating season. A recorded case involved a group of five females with just one crippled male. Three receptive females approached and mated with out-group males. These males invaded the group and forcibly mated with two females that had suckling young from the previous year, injuring the females in the process and resulting in death of their infants (at least one of the infants was killed by one of the males). At this time, the resident male left the group, returning only when all but two of the outgroup males had left. Two females and two males took up residence as a result ofthis influx. This event was not seen as typical or characteristic of the Bonnet Macaque, but the result of occasional opportunism as a breeding strategy by males. The gestation period lasts 162 days. Births occur during the dry season in January—May, with a peak in February-April. Single offspring are born to females about every year. Neonates are generally almost black. Young are nursed for 8-12 months, and sexual maturity of both males and females occurs at 2-5-3-5 years old. The female first gives birth at c.4-5 years old. Mean interbirth interval with a surviving infant is 458-6 days, but when an infant is lost, it drops to 382-5 days. Despite reaching sexual maturity, males are not socially mature for another 2-3 years. Lactating females have a dark red face compared with non-lactating females that have a pale pink face. Individuals may live for ¢.30 years.

Activity patterns. The Bonnet Macaque is diurnal, arboreal, and terrestrial. Daytime activity in natural forested areas is ¢.90% arboreal and ¢.10% terrestrial. In more open vegetation, such as cultivated areas,it is more terrestrial; about 30% ofits daytime activity. At night, they sleep in trees, except in urban areas where they sleep on roofs and ledges. A year-long study ofa forest group provided the following activity budget: 37% foraging, 30% engaged in social activities, 21% resting, 7% traveling, and 5% engaged in miscellaneousactivities. Feeding is particularly intense in the early morning and late afternoon. Much oftheir terrestrial foraging is for animal prey. Urban groups suffering food shortage and being exposed to predators and, at least in many cases, harassment from people spend more time on the move (20%) than rural and forest groups.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of Bonnet Macaques in forests and farmland and along roadsides average 29 individuals (range 7-75). Depending on the region and customs (extent of persecution or provisioning), groups in urban areas are a little smaller and average 21 individuals (range 10-43), or they may be considerably larger, averaging more than 40 individuals. Groups are multimale—multifemale. Groups have 1-8 adult and subadult males and 2-11 adult and subadult females, with a mean sex ratio of reproductive adult males and females of 1:1-2. Home ranges of different groups overlap with others (5-25% but sometimes 100%), and encounters between groups are frequent. Males are generally quite tolerant; they often huddle together, have a high frequency of affiliative social interactions with each other, and havelittle difficulty immigrating among groups. The hierarchy among males is weak and not very linear. Bonnet Macaques have frequent intergroup encounters, and adult and subadult males collaborate in defending their females and their territory (food resources). Males disperse, and females are generally philopatric, although females will change groups in the wild. Solitary individuals have not been observed. All-male groups are infrequent, but they have been seen (e.g. Darkbellied Bonnet Macaque in Bandipur and Mudumalai national parks). Home ranges average ¢.200 ha in natural areas and c. 100 ha in urban areas. In the wild, male Bonnet Macaques lead the group, control fighting between group members, give alarm calls (vigilance), and defend the group in times of danger. Males form coalitions , targeting individuals with which they had had a previous conflict, but otherwise male— male relations are generally placid. Resting clumped in passive contact is typical of the Bonnet Macaque, in contrast with Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques ( M. nemestrina ) and Lion-Tailed Macaques ( M. silenus ) that huddle infrequently. Male—female mounting is solicited by the male, and the male’s position in mounting is seen as a display of dominance. Female—female mounting and male-male mounting have also been observed. Alloparenting is common, with females showing interest in and trying to carry and care for infants of other females. Natural predators are believed to include Tigers (Panthera tigris), Leopards (P. pardus), small cats, large raptors, crocodiles, large snakes, and, particularly in urban areas, domestic dogs. Group members cooperate when fighting predators. Bonnet Macaques have been observed chasing Golden Jackals (Canis aureus).

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red Last, including both subspecies. Bonnet Macaques are hunted in parts of their distribution, and live individuals are occasionally traded for use in biomedical research and road shows. They are viewed as pests by farmers and horticulturists in somevillages and semi-urban areas, resulting in conflicts. Crop-raiding Bonnet Macaques are shot or captured and transported to distant forests. The southward distributional extension of the Rhesus Macaque ( M. mulatta ) poses some threat to the smaller Bonnet Macaque through competition and aggression. Although they are listed as Least Concern, the Bonnet Macaque has undergone significant declines throughoutits distribution. One long-term study indicated a decline of 41-5% in the last 20 years and another study in commensal areas, a decline of 21-5% in 20 years. Although Bonnet Macaques appear to adapt well to urban environments and temple grounds, a survey of 107 temples and tourist spots in the state of Karnataka found macaque groups at 37 of them and found they had been eliminated from 51, most particularly in the coastal region. There is a high probability of further declines in conflict zones in the nearto mid-term future. Further research and surveys are needed to reassess the status of Bonnet Macaques in southern India. The Dark-bellied Bonnet Macaque is known to occur in numerous national parks, including Bandipur, Bannerghatta, Eravikulam, Kudremukh, Mollem, Mudumalai, Mukurthi, Nagarhole, Sanjay Gandhi, Silent Valley, Sri Venkateswara, and Nagarjunasagar Sirisailam, and a large number of wildlife sanctuaries. The Light-bellied Bonnet Macaque occurs in Periyar National Park and nine wildlife sanctuaries: Grizzled Squirrel, Kalakkadu, Mundanthurai, Neyyar, Peechi Vazhani, Peppara, Periyar, Point Calimere, and Shendurney.

Bibliography. Boccia et al. (1988), Burton & Sawchuk (1982), Clarke (1978), Defler (1978), Fooden (1981), Fooden et al. (1981), Hohmann (1989b), Krishnamani (1994), Kumar et al. (2011), Kumara, Kumar & Singh (2010), Kumara, Singh et al. (2010), Molur et al. (2003), Nair & Jayson (1988), Nair et al. (1985), Nolte (1956), Parker & Hendrickx (1975), Rahaman & Parthasarathy (1967, 1968, 1969a, 1969b), Ramachandran (1995), Ramakrishnan & Coss (2000a, 2000b, 2001), Roonwal & Mohnot (1977), Samuels et al. (1984), Silk (1980, 1982, 1988a, 1988b, 1999), Silk & Samuels (1984), Silk et al. (1981a, 1981b), Simonds (1973), Singh & Vinathe (1990), Singh, Akram & Pirta (1984), Singh, Erinjery et al. (2011), Singh, Jeyaraj et al. (2011), Singh, Kumara et al. (2006), Sinha (2001), Sugiyama (1971).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.