Macaca nemestrina (Linnaeus, 1766)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863159 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFC9-FFCD-FADC-6357F997F5A9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca nemestrina |

| status |

|

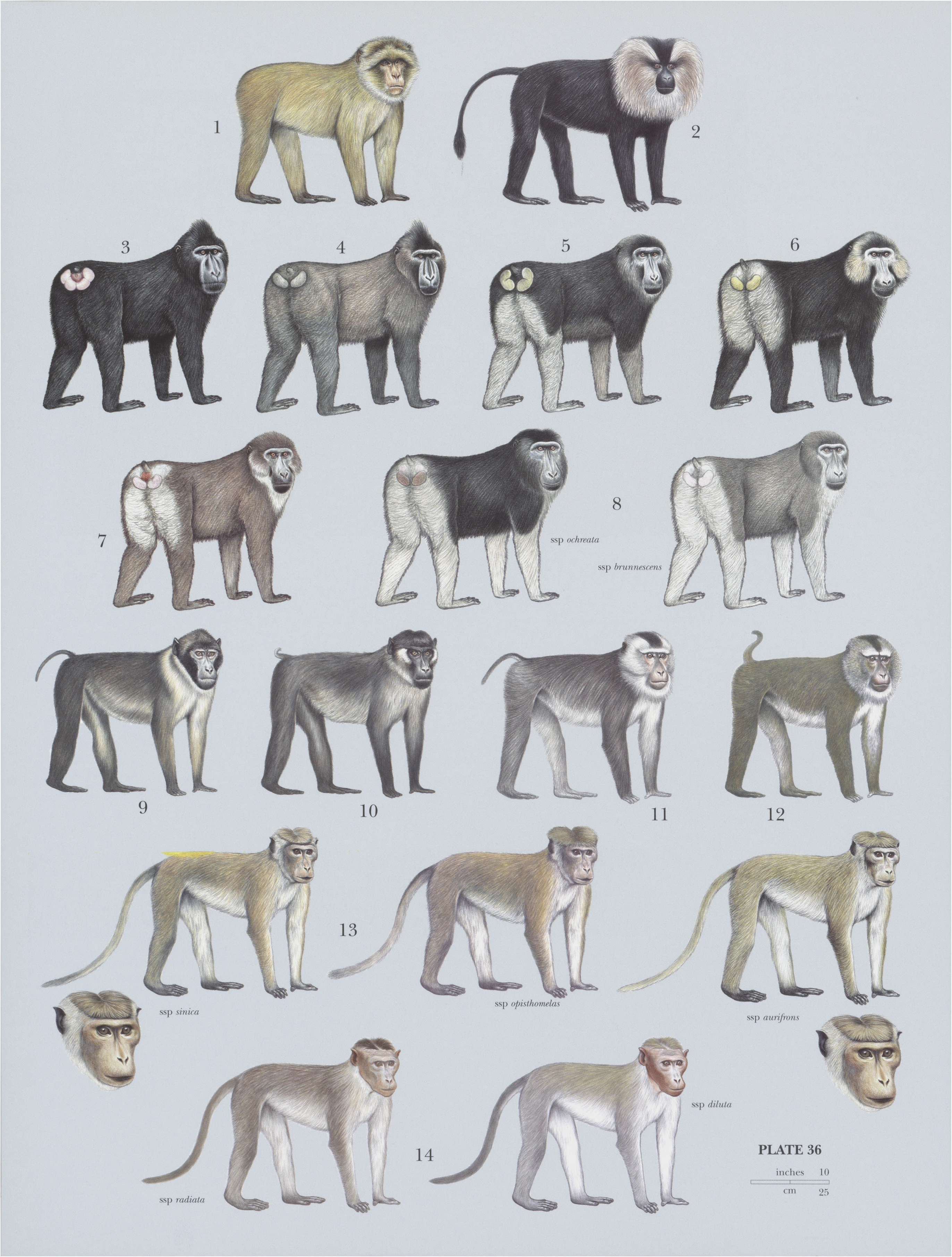

11. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque

French: Macaque a queue de cochon / German: Sidlicher Schweinsaffe / Spanish: Macaco de cola de cerdo meridional

Other common names: Pigtail Macaque, Pig-tailed Macaque, Southern Pig-tailed Macaque, Sundaland Pig-tailed Macaque

Taxonomy. Simia nemestrina Linnaeus, 1766 ,

Sumatra.

M. nemestrina has a characteristic helmet-shaped and bluntly bilobed glans penis, with the breadth of the glans 60-89% of its length, that has resulted in assignment to various species groups of macaques, including the silenus-sylvanus species group ( M. sylvanus , M. sinica , M. nemestrina , and the Sulawesi species) and more recently the nemestrina species group (M. nemestrina, M. silenus , M. leonina , M. pagensis ). M. leonina and M. pagensis were formerly considered subspecies M. nemestrina . Distributions of M. nemestrina and M. leonina are contiguous in peninsular Thailand (between 8° N and 9° N) at the southern end of the Isthmus of Kra, and apparently restricted hybridization has occurred between them, including on the islands of Phuket and Yao Yai. Mid-Pleistocene fossils referable to the genus Macaca have been collected in eastern Java and may be ancestral to living M. nemestrina , an interpretation that implies that the pig-tailed stock inhabited Java during the Pleistocene and subsequently became locally extinct, as did other mammals, including the primates Siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) and orangutan (Pongo). Prehistoric Holocene subfossils, collected on the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra, dating within the past 10,000 years, suggest a greater abundance of M. nemestrina in the western part of the Sunda area than presently occurs there. The Sunda Shelf (Sundaland) was most recently exposed during the last glacial maximum c.18,000 years ago. Morphological similarity characterizes now disjunct insular and peninsular populations. Monotypic.

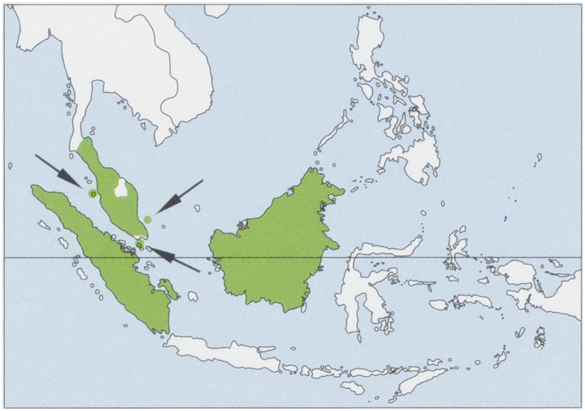

Distribution. Sunda area from the Surat Thani-Krabi depression in peninsular Thailand (8-9? N) SE through Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Bangka, and Borneo; apparently native to offshore islets of Pinang (W coast of Peninsular Malaysia), Tioman (E coast of Peninsular Malaysia), and Batam (Riau Archipelago off the S tip of Peninsular Malaysia). It is thought to have been introduced to other offshore islets. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 53.2-73.8 cm (males) and 43.4-57.6 cm (females), tail 16-24 cm (males) and 13-25 cm (females); weight 10-13.6 kg (males) and 5.4-7.6 kg (females). The Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque is sexually dimorphic, males being a little less than twice the weight of females. Pelage of the trunk is yellowish-brown agouti to golden-brown agouti, including lateral surfaces of trunk and limbs and dorsal surface of appendages. There is a variably developed blackish mid-dorsal streak or patch that becomes more or less indistinct in the scapular region. Dorsal hairs are longest (7-9 cm) at the scapula in adult males. Indistinct dark streaks frequently occur on posterior surfaces of shanks. Underparts are thinly haired, whitish to ocherous-buff anteriorly, often becoming darker (buffy to pale brown) on the abdomen. Crown hairs are short and blackish, and they radiate to form a whorl at the top of the head. Crown patch is broad in front and extendslaterally on the supraorbital region as far as outer angles of the eyes. Cheek hairs are relatively short, pale at the base, and blackish at the tips, forming a pair of dark streaks or sideburns. The Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque has a long muzzle of pale brownish skin, thinly covered with inconspicuous short whitish hairs. Tail is thin, sharply defined blackish dorsally and pale ochrerous-buft ventrally; elongated terminal hairs frequently form an inconspicuous tuft. Tail is carried arched rearward and tip directed downward. Neonates are black. At about three months old, infant pelage changes to transitional brown and then to a tan agouti similar to adults.

Habitat. Highest densities are found in lowland and hill dipterocarp rainforests. Although Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques occur from sea level to 1900 m, they prefer the higher elevations and dry ground at the foot of hills and slopes. They are present in lowland and swamp forest in Peninsular Malaysia. They are not regular residents of swamp forest in Sumatra but may enter freshwater swamps during months of lowest rainfall when many tree species are flowering or fruiting. They frequently occur adjacent to agricultural land, including hillside farms, and on fringes of urban environments. They may travel together, sometimes simultaneously, with Long-tailed Macaques ( M. fascicularis ) in lowland primary and secondary forest and degraded habitats.

Food and Feeding. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques are mainly frugivorous but include leaves and invertebrates in their diet. During an 18month study in Peninsular Malaysia, the diet consisted of fruits (742%), leaves and buds (11:1%), flowers (11%), invertebrates (12:2%), and other items (1:4%). Swarming termites, grasshoppers and other insects, and spiders were consumed elsewhere in Peninsular Malaysia, in addition to fruits, seeds, young leaves, leaf stems, and fungi. They eat figs ( Ficus , Moraceae ), other fruits, leaves, and miscellaneous food items in North Sumatra. Crop raiding is characteristic of the Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque. During a 14month survey in Sumatra, more than 20% of encounters occurred when the macaques were raiding farms. They appear to raid fields on a circuit, depending on the location and availability of crops. They concentrate on large fruits and exploit food resources that their relatively large size and strength assist them in obtaining—e.g. oil palm fruit, mature corn ears, thick and spiny-skinned durian fruit, and tapioca (cassava) roots. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques also raid papaya, which can be quickly picked and transported to the forest edge for uninterrupted consumption. A field may be raided daily until a favorite crop, such as corn, is completely destroyed. They raid with stealth, frequently surveying a field for some time before entering it, one individual at a ime and rarely as a group. A lookout, often a subadult male, may keep watch from a tree at the forest edge, making a warning bark when humans approach. Infants taken from the wild and raised by humans are trained at 2-5 years old to respond to verbal commands to choose and pick coconuts. An efficient picker can harvest 500-1000 coconuts/day from a palm plantation. In Peninsular Malaysia, Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques sometimes are seen, frequently in association with Long tailed Macaques, scavenging through roadside garbage or begging for food from passing motorists.

Breeding. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques show no synchrony or seasonality in sexual cycling. Mating occurs throughout the year, although there may be a slight peak in January—May. Females have a characteristic cyclical circumanal sexual swelling. Swelling develops gradually, beginning during or immediately after the menstrual period and reaches maximal tumescence in c.15 days (at which maximal sexual behavior occurs in females and males). At maximum size, the engorged pinkish, and hairless area extends from the base oftail to the ventral border of the ischial callosities (seating pads), which are partly buried in the swelling, and extends laterally over an area twice the breadth of both callosities. Thinly haired skin anterior to the vulva (mons pubis) is less conspicuously swollen. Swelling rapidly subsides following ovulation, usually within 1-2 days after maximum tumescence. The first swelling may occur at 2-5 years old in captivity. The male’s broad, helmet-shaped glans penis has been described as “pale crimson.” The length of the baculum (penis bone) averages about 16-1-21-1 mm and the shaft is nearly cylindrical. The female’s cervix and cervical colliculi correspondingly are moderately large. In captivity, female Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques are sexually mature at three years old and males at 4-5 years old. Females typically solicit sexual advances of males by presenting their rump after approaching males from behind and standing in front of them. Males may initiate copulation with females by showing the “pucker” or “protruded lip face,” which is unique to the Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque. Copulation usually consists of a series of non-ejaculatory mounts that precede the ejaculatory mount (multimount ejaculator): 7-11 mounts are the median per ejaculation. A single offspring is born after a gestation averaging 172 days. Captive birth weights are 442-3-474-4 ¢ for female infants and 476-6-515-7 g for male infants. Age of weaning averages close to eleven months in captivity. Interbirth interval in natural populations may be two years. There is no record of infanticide in the wild. Known maximum longevity in captivity is 37-6 years.

Activity patterns. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques appear to spend more time traveling, and on the ground, than foraging and feeding. They flee quietly on the ground when disturbed. During a 14month survey in Sumatra, 36 contacts were made while the macaques were traveling (38:9%) or fleeing (25%) compared with feeding (5-6%) or sitting (11-1%). In another study in Eastern Kalimantan, traveling or foraging on the ground accounted for 67% of contacts. An adjusted daily activity budget of locomotion (61%), resting (19%), foraging (16%), and social behavior (4%) was recorded during an 18month study in tropical rainforest in Peninsular Malaysia. In north Sumatran forests, Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques generally forage in small, widely dispersed subgroups that travel on the ground and seldom remain in the same place for long; they search for miscellaneous food items on the ground but more often feed in trees. Contact is maintained with a low vocalization audible at distances of 30-80 m. A common pattern appears to be sleeping in broad-crowned emergents at the fringe of primary forest and entering secondary or degraded forest to raid cropland. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques may vocalize as they approach sleeping trees at dusk. At other times, they can be so silent that they are difficult to observe.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques are wide ranging, with home ranges of at least 100-300 ha, parts of which may be used infrequently. Considerable home range overlap was reported in western Sumatra. Daily movements are ¢.600 m in north Sumatra. Groups are multimale-multifemale. The adult male-female sex ratio has been found to vary from 1:8 in 13 groups of 15-55 individuals (average 24) to 1:2-7 (including adult and subadult mature males) in three groups of 49-81 individuals. Females remain in natal groups, and males emigrate at 5-6 years old. Both solitary adult and subadult males have been observed. Dominance hierarchies exist in both sexes. Adult males are dominant over females and may attack them at feeding sites, although groups of females (perhaps kin) may attack lower ranking males. Censuses in west-central Sumatra in 1996-1999 yielded density estimates of 1-7 groups/km? in lowland forest, 1-5 groups/km? in hill dipterocarp forest, 0-7 groups/km* in montane forest, and 0-8 groups/km? in submontane forest. Average group size was 10-5 individuals (range 1-20) in hill dipterocarp forest, seven individuals (range 6-8) in montane forest, 9-5 individuals in submontane forest, and 8-5 individuals (range 1-13) in lowland forest.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque has become seriously threatened and its populations fragmented by human encroachment and habitat loss, from legal and illegal logging, traditional and modern monoculture crop plantations such as oil palm, land clearance for agriculture and new settlements/ transmigration, forest fires and drought (as have occurred in Kalimantan), and hunting for the illegal pet trade. Lowland forest 1s most seriously threatened by a variety of human activities. Tropical rainforest, especially in lowlands, has disappeared rapidly in Sumatra, with most land being converted to commercial timber concessions, cultivated lands, and human settlements. The spread of oil palm plantations is one of the greatest threats to forests in Indonesia and Malaysia. From 1967 to 2000, the area under cultivation in oil palm in Indonesia expanded from less than 2000 km® to more than 30,000 km®. Indonesian production of crude palm oil was expected to reach a new high of 22-4 million tons in 2010, up 1-7 million tons in 2009. Production of palm oil is a major industry in Peninsular Malaysia, where Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques experienced an estimated decline of 43-7% from 80,000 individuals in 1957 to 45,000 in 1975. Sabah and Sarawak have become the two big Malaysian oil palm states. Ultimately, the great majority of Sabah’s forest may consist of logged dipterocarp forest. There are many instances of conflict between humans and Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques, which has caused them to be regarded as a crop pest by farmers. Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques are found throughout Sarawak, for example, and can survive in logged forest but are hunted intensely for food and sport, and especially as crop pests in many areas. Along with the Long-tailed Macaque, they account for more than 2% of mammals hunted in Sarawak and appear to be held at low density because of hunting. The Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque is naturally rare, and its groups are highly mobile so local populations are vulnerable to extirpation by hunting around farms. Trading of Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques for export by quota still occurs in Indonesia, and Sumatra is the main source. They are used as models for biomedical studies, including HIV/Aids research. Lower densities of Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques were recorded in Sumatra during surveys between 1996 and 1999 than those observed in the 1970s. From 1977 to 1979, Peninsular Malaysia was the principal supplier of Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques to the United States, the world’s largest user of primates, supplying ¢.970 individuals; imports from Indonesia totaled 570 individuals between 1976 and 1980. During 1978-2011, for which a record of international trade is available, more than 11,000 Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques may have been exported, with the United States being the major recipient. Numbers exported from Malaysia in 1977-1984 were significantly less. A total ban on the export of primates went into effect in Malaysia on 15 June 1984.

Bibliography. Abegg & Thierry (2002a), Agy et al. (1992), Anonymous (2010), Bennett et al. (1986), Bernstein (1967), Caldecott (1986), Cawthon Lang (2005), Crockett & Wilson (1980), Fooden (1975, 1976), Jintanugool et al. (1985), Kappeler & Pereira (2003), Khan et al. (1985), Lekagul & McNeely (1988), Lim Boo Liat (1969), Mack & Eudey (1984), MacKinnon (1986), Medway (1972), Oi (1990, 1996), Payne (1985), Rijksen (1978), Rodman (1973), Sandu (2010), Sackett & Kroeker (undated), Sponsel et al. (2002), UNEP-WCMC (2012), Yanuar et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.