Macaca leonina (Blyth, 1863)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6864250 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFC8-FFCE-FAC6-6F8DF7EBF275 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca leonina |

| status |

|

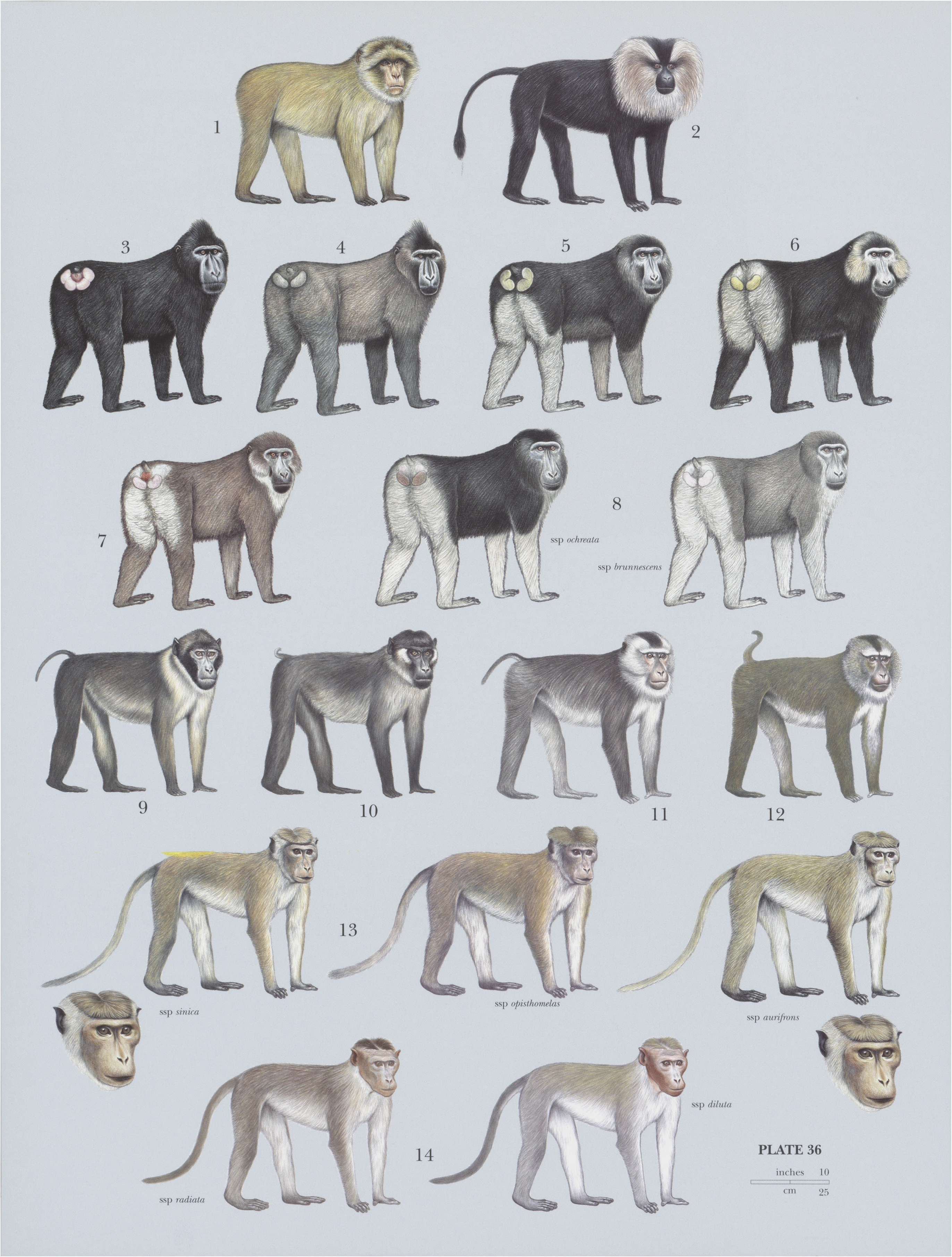

12. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Northern Pig-tailed Macaque

French: Macaque de Birmanie / German: Nordlicher Schweinsaffe / Spanish: Macaco de cola de cerdo septentrional

Other common names: Burmese Pig-tailed Macaque, Long-haired Pig-tailed Macaque

Taxonomy. Inuus leoninus Blyth, 1863 ,

“Mountainous and rocky situation,” Arakan District, south-eastern Burma .

Until recently, M. leonina was classified as a subspecies of M. nemestrina . It has a characteristic helmet-shaped and bluntly bilobed glans penis, with the breadth of the glans 59-89% of its length that has resulted in its assignment to various species groups of macaques. It is currently aligned with the nemestrina species group, including M. nemestrina , M. leonina , M. silenus , and M. pagensis . Distributions of M. leonina and M. nemestrina are contiguous in peninsular Thailand (between 8° N and 9° N) at the southern end of the Isthmus of Kra, and apparently restricted hybridization has occurred between them. Monotypic.

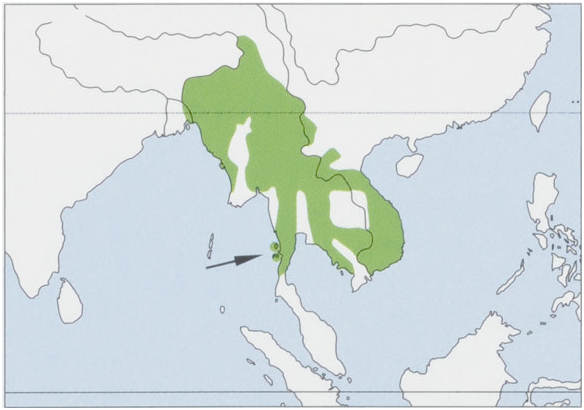

Distribution. NE India (S of the Brahmaputra River in the states of Assam, E Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland & Tripura), extending SE through E Bangladesh and Myanmar (including the Mergui Archipelago), S China (SW Yunnan Province), Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia; S to the Surat Thani/Krabi depression in peninsular Thailand (8-9° N). The lack of records in C and NE Myanmar between 20° N and 25° N suggests that this may be a natural gap in the distribution of the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 50-59.5 cm (males) and 40-49 cm (females), tail 18-25 cm (males) and 16-20 cm (females); weight 6.2-9.1 kg (males) and 4.4-5.7 kg (females). Dorsal pelage of the trunk of the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is yellowishbrown agouti to golden-brown agouti anteriorly, becoming slightly drabber posteriorly, with lateral surface of the trunk and limbs similar in color. Hairs on the scapular region of adult males are 7-10 cm long. Chest and anterior surfaces of shoulders are a pale ocherous-buff, with underparts thinly haired, pale yellowish-brown to whitish, especially in females. Fur of the short, thin tail is blackish dorsally and buffy ventrally, with the tail base set off by a pair of projecting tufts of whitish fur . Tail is not invariably carried arched over the back, with tip directed upward and forward as frequently described, but may drop backward. The crown is short-haired, with a dark-brown patch extending in front about as far as the middle of the eyes. Cheek ruff is long and pale ocherous-buff, tending to hide the ears when seen from the front. A reddish streak extends laterally from the outer corner of each eye to cheek whiskers in males. Skin around eyesis a sharply defined pale bluish white. Muzzle is relatively short, with pale brownish skin densely covered with short buffy hairs. Pelage of adult females is somewhat shorter, paler, and drabber than that of males. Neonates are black. Pelage of infants changes to transitional brown a few months after birth. Immature Northern Pigtailed Macaques are generally paler and drabber than adult females, and the agouti pattern is less developed.

Habitat. Dense evergreen and semi-evergreen forest, both tropical and subtropical, and deciduous forest in plains, foothills, and hills at elevations below 50 m to more than 2000 m. The Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is found in lowland primary and secondary forest and open habitats such as pine and dry dipterocarp forest and coastal, swamp, and montane forest. It is frequently observed in riparian habitat in western Thailand and Laos. It occasionally enters tea plantations in north-eastern India and has been seen in the vicinity of human settlements and cultivated fields in India and Laos, where it was relatively common in some areas in the 1990s, even in highly degraded regions. The Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is similar in some morphological characteristics, behaviors, and ecological requirements to the Assamese Macaque (M. assamensis ); their distributions overlap along the foothills of the South-east Asian mountain chains. The home ranges of two groups of Northern Pig-tailed Macaques overlapped with three groups of Assamese Macaques in Assam (India). Northern Pigtailed Macaques, specifically an adult male and female with an infant on her ventrum, have been observed traveling with a group of Assamese Macaques in a mosaic of deciduous and dry evergreen forest in western Thailand. The two species share habitat in Laos from 15° N to 20° N.

Food and Feeding. In eastern Assam, India, fruit comprises 65-9% of the diet of the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque. They eat parts of more than 91 kinds of plants, including mature and tender leaves, leaf buds, leaf petioles, seeds, stems, climbers, roots, flowers, flower buds, inflorescences, bamboo shoots, and gums. They also eat insects and larvae, termite eggs, and spiders. Although crop-raiding is considered to be rare in north-eastern India, Northern Pig-tailed Macaques have been observed feeding in rice paddy after harvest as well as in fields of corn. They also eat fruits and vegetables grown by hill tribes in slash-and-burn cultivation (“jhum”). Recently, Northern Pigtailed Macaques have begun to beg for food, as they do in Khao Yai National Park, Thailand, where a few habituated groups may depend substantially upon biscuits, fruit, and other items from tourists.

Breeding. Northern Pig-tailed Macaques appear to have a marked winter-spring breeding season in north-eastern India. Females are sexually receptive in August-December, but a few females may be receptive until February. Newborns appear in mid-January to early May, with a few in June. Limited data suggest two birth peaks in western Thailand, approximately in June and December. Permanent canines erupt and puberty begins in males at c.4-5 years old. Subsequently, the sizes of the glans penis and baculum (penis bone) increase rapidly, at a rate aboutfive times that of head-body length. The broad, helmetshaped glans penis is pinkish. The length of the baculum averages about 21-26-7 mm and is 25% greater than in the Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque ( M. nemestrina ). The female's cervix and cervical colliculi correspondingly are moderately large. The sexual skin swelling is especially developed in female pig-tailed macaques and corresponds to their ovulatory cycle—reddish swelling occurs at mid-cycle and extends to the tail root. Swellings of Northern Pig-tailed Macaques resemble that of the Liontailed Macaques ( M. silenus ). They do not form a continuous pillow-like mass as in Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques but are subdivided into five separate swollen areas, with the subcaudal swelling being highly developed. A female's first swelling probably occurs at 2-5-3-8 years of age, as inferred from Sunda Pig-tailed Macaques and Lion-tailed Macaques. Females typically solicit sexual advances of males, presenting their rump after approaching males from behind and standing in front of them. Copulation usually consists of a series of non-ejaculatory mounts that precede the ejaculatory mount (multi-mount ejaculators). In a wild population, each mounting bout was 2-16 seconds, and number of thrusts was 3-23. A dominant male completed seven copulation bouts in two hours and 23 minutes but also 16 copulation bouts in 30 minutes. One female participated in copulation bouts for 20 days. After copulation bouts, the male sometimes utters a low bark. Post-copulatory grooming may occur; usually the female grooms the male. A single young is born after a probable gestation of 171-180 days. Gestation periods of 162-186 days and 167-179 days have been recorded in captivity. Captive individuals may live into their 30s.

Activity patterns. Northern Pig-tailed Macaques are primarily arboreal but may use both terrestrial and arboreal pathways, vocalizing to maintain auditory contact while traveling in a single file or in subgroups. They flee from danger through the trees, not on the ground. They do travel on the ground when crossing clearings and roads and to forage and feed in degraded areas and on crops. The amount of time spent on the ground to feed on crops fluctuates seasonally and by group. At one studysite in Assam, 38% of the group’s time was spent on the ground in January when foraging in harvested rice paddy. At another site, as much as 20% of daytime was spent on the ground in February-March feeding on sugar cane left over by foraging wild Asian Elephants (Elaphas maximus). Some detailed observations were made on the activity of Northern Pig-tailed Macaques in eastern and central Assam in 1992-1994 and 2004. From just after dawn, they had three peaks of feeding and a long midday rest, with shorter spells of resting in mid-morning and late afternoon. Average percentage of time spent in different activities was: resting (including preparation for night roosting) ¢.45%, feeding 23-5%, locomotion 17-19-4%, and grooming nearly 6-8%. Actual time spent feeding was 158-229 minutes/day. Foraging for grain or seeds in harvested paddy occupied 65% of feeding time in January in one area. In the presence of sexually receptive females, copulation became a major activity. A dominant male and a receptive female, who also copulated with a second male, spent as much as 33-7% and 56-5% of their respective time in copulation and related activities such as post-copulatory grooming and resting between copulatory bouts.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In eastern and central Assam, home ranges of Northern Pig-tailed Macaques are 83-347 ha, and overlap by about 25-48%. Daily movement is 690-2240 m and is apparently influenced by weather conditions and the availability of seasonal fruit. Daily movement increased in degraded areas where fruiting trees were far apart. Groups are multimale-multifemale. The sex ratio recorded in Assam is 1:5-5. It is assumed that males leave their natal groups at or before puberty to disperse to other groups. Both subadult and adult solitary males have been recorded. A linear dominance hierarchy among males was observed during the mating cycle in Assam, where the alpha male may lead group movement. Group size of the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is 12-40 individuals. Exact counts of 16-33 individuals were recorded for seven groups in Assam. Estimated group sizes in Laos rarely exceed 20-30 individuals. There are a few records of groups numbering 50-150 individuals in Khao Yai National Park in Thailand, Dak Lak Province in Vietnam, and Dong Phou Vieng National Biodiversity Conservation Area in Laos. Such large groupings may be of two or more groups foraging and feeding together.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The [UCN Red List. In South Asia, the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is restricted to numerous fragmented locations, and appears to be few in numbers. There is little left ofits preferred habitat of dense forest. It is considered critically endangered in Bangladesh and endangered in India. Forest destruction and degradation are caused by tree felling, human encroachment, monoculture tree plantations, fisheries (in Bangladesh), and slash-and-burn shifting cultivation by cultural minorities or hill tribes (jhum in India). The Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is killed for food by many hill tribes in north-eastern India that increasingly have access to automatic firearms. Poaching has been rampant in some areas such as the Assam-Mizoram border. In China, the Northern Pig-tailed Macaque is variously classified as rare and endangered and was thought to number c.1000 about the year 2000. It was classified as vulnerable in the Red Data Book of Vietnam in the 1990s. Poaching for traditional medicine, stimulated by increasing affluence in the country (and overall in East Asia), is now putting extreme pressure on all primate populations in Vietnam, and no new conservation measures have been introduced. Direct threats to the habitat include logging, gold mining, and shifting cultivation by minority peoples. Elsewhere in the Indochinese Peninsula, development of the economy and infrastructure are resulting in habitat loss and degradation. In Laos, the Northern Pig-tailed Macaqueis listed as potentially at risk. Hunting for food by villagers does occur, and it may be affected by opportunistic hunting to supply bones to Vietnam for traditional medicine. Although these threats are in incipient stages, agriculture (especially commodity crops), mining, and hydropower are causing significant loss of forest habitat in Laos. In Cambodia, where Northern Pig-tailed Macaques are reported in only five of 24 provinces, use in traditional medicine, loss of habitat from logging, and especially trade constitute major threats to primate populations. Economic land concessions and mining concessions occur even within protected areas. Logging, plantations, aquaculture, hunting for food and pets, and political unrest in cultural minority states impact primates, including Northern Pig-tailed Macaques, in Myanmar. Factors associated with substantial economic development, such as timber extraction, large-scale farms and plantations,irrigation and hydroelectric projects, highway construction, mineral exploration, resettlement programs for hill tribes and others, and recreation and tourism have significantly reduced forest cover in Thailand. Shifting cultivation of hill tribes and ethnic Thais also has resulted in large areas of forest being cleared. Illegal hunting for sale (market hunting) and poaching for food near villages can directly impact primate populations, including Northern Pigtailed Macaques. The Western Conservation Corridor in western Thailand may offer some protection to both habitat and wildlife.

Bibliography. Abegg & Thierry (2002a), Choudhury (2003, 2008a, 2009, 2010), Duckworth et al. (1999), Eudey (1979, 1980, 1981, 1991), Fooden (1971, 1975, 1976, 1982), Gippoliti (2001), Groves (2001), Hamada, Kawamoto, Kurita et al. (2009), Hamada, Kawamoto, Oi et al. (2009), Jintanugool et al. (1985), Kingsada et al. (2010), Kuehn et al. (1965), Pathonthong et al. (2009), Mukherjee (1982), Molur et al. (2003), San et al. (2009), Thao et al. (2010), Tokuda et al. (1968), Vietnam, Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (1992), Zhang Rongzu & Quan Guogiang (1996), Zhang Yongzu et al. (2002).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.