Macaca tonkeana (Meyer, 1899)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863147 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFC4-FFC2-FAC6-6CC6F752FC22 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca tonkeana |

| status |

|

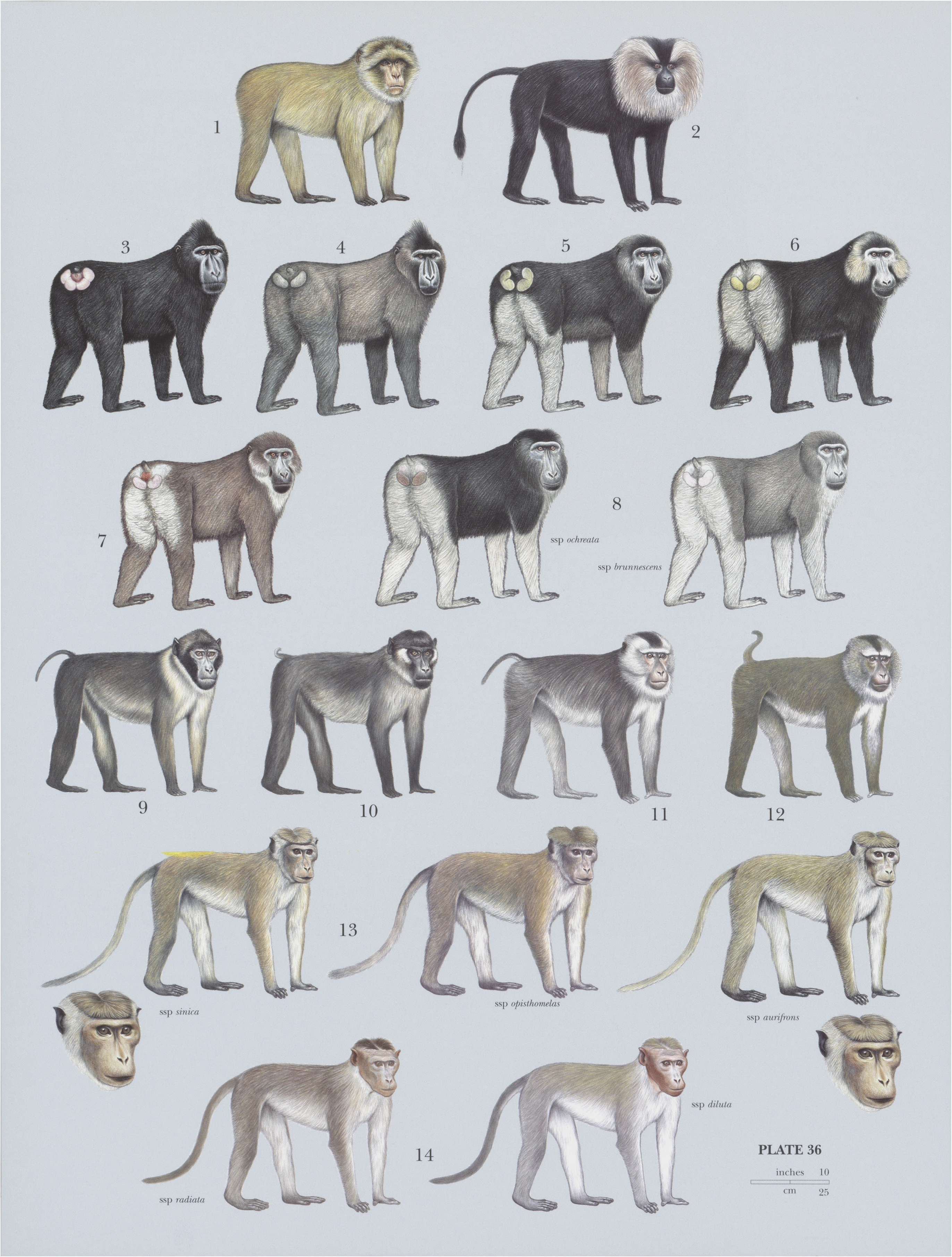

6. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Tonkean Macaque

French: Macaque tonkéen / German: Tonkean-Makak / Spanish: Macaco de Togian

Other common names: Tonkean Black Macaque

Taxonomy. Macacus tonkeanus Meyer, 1899 ,

Indonesia, Sulawesi Tengah.

M. tonkeana hybridizes with M. ochreata , M. maura , and M. hecki in areas where their distributions overlap. Genetic studies have found little evidence of substantial gene flow between parental species outside of the narrow hybrid zones. Based on morphometric and dermatoglyphic (fingerprint) data, eastern populations (east of Bongka River, including those found on the Togian Islands) were proposed to constitute a separate species, M. togeanus, the “Balantak Macaque.” Subsequent molecular research, however, did not identify any fixed molecular markers in nuclear DNA that would support a separate species status for these populations. Monotypic.

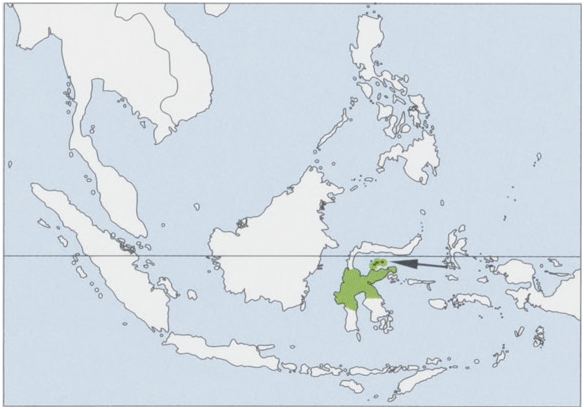

Distribution. C Sulawesi (S to Latimojong, SW to the base of the Toraja highlands at the Tempe Depression, SE toward, but not at, the lakes region of the SE peninsula, and NW to the isthmus between Palu and Parigi) and Togian Is. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 58-68 cm (males) and 50-57 cm (females), tail 4-7 cm (males) and 3-6 cm (females); weight 10-12 kg (males) and 8:6-10.4 kg (females). The Tonkean Macaque has black pelage, with white hair on the rump, dorsal parts of hindlimbs, and parts of the ventrum. Cheek tufts are prominent and range in color from pale brownish-gray to a pale brownish-yellow. Supraorbital ridges are strongly developed. There is a sagittal crest, and the muzzle is elongated, with lateral ridges. Ischial callosities are oval-shaped and orange-toned, and they have recently been characterized (along with those of the Moor Macaque, M. maura ) as Type 1: oval without bending. Some show graying or whitening on their face, particularly around their eyes, head, and back, or entire bodies.

Habitat. Primary and secondary tropical rainforest at predominantly hill (400-850 m) and upland (850-1500 m) elevations, but also in montane forest (1500-2500 m). Tonkean Macaques can also exist in anthropogenically altered environments, incorporating agricultural areas into their usable habitat. Rainfall and the availability of forest fruit show fairly uniform temporal distributions in Lore Lindu National Park. Figs ( Ficus , Moraceae ), an important food resource for much of the Sulawesi fauna, are very abundant in Lore Lindu (34-8 figs/ha) compared with other Indonesian forests (6-6 figs/ha, East Kalimantan Province and 7-10 figs/ha, North Sulawesi Province). Tonkean Macaques are frequently found in association with the endemic yellow-billed malkoha (Phaenicophaeus calyorhynchus). Malkohas benefit from insect prey flushed from the forest canopy by moving macaques.

Food and Feeding. Tonkean Macaques have a diverse diet (more than 55 plant species). Ripe fruit makes up the largest part (c.70-80%). Key fruit species include Ficus (Moraceae) , Elmernillia tsiampacca ( Magnoliaceae ), Artocarpus (Moraceae) , Pandanus (Pandanaceae) , Pangium edule ( Salicaceae ), and, particularly in anthropogenically altered areas, the sugar palm ( Arenga pinnata, Arecaceae ). Insects, young leaves, shoots, and stalks (13-18% ofdiet) are also frequently consumed. Groupsliving in close proximity to agricultural land incorporate cultivated crops into their diet (e.g. bananas, papaya, maize, cacao, sweet potato, and legumes).

Breeding. Reproductive data come from captive populations of Tonkean Macaques. Females begin cycling at 4-5 years old, have a mean cycle length of 37-41 days, and exhibit a pronounced, bright pink to red sexual swelling during the periovulatory period. In young females, the only area that reddens and swells is between the anus and the base of the tail. As females age, the swelling becomes larger and more pronounced. A distinctive feature of Tonkean Macaques is the appearance of two tumescent lumps on the rump that develop under the fur on both sides of the spine. Mean duration of genital swelling is 13 days. Consortships begin at the time of swelling and last 5-10 days. A single offspring is born after a mean gestation of 173 days. In the wild, some female Tonkean Macaques have a one-year interbirth interval.

Activity patterns. Tonkean Macaques are diurnal, arboreal, and terrestrial. Increased terrestriality (more than 20% of behavioral records) and more time devoted to foraging were observed in disturbed habitat. Groups spend, on average, 34% of their day resting, 33% moving, 23% foraging and feeding, and 10% socializing. Several cases of tool use have been observed in captive groups of Tonkean Macaques (e.g. using sticks to obtain food and leaning a log against a wall to climb on it).

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Tonkean Macaques live in multimale-multifemale groups. Mean group size is 24 individuals (range 6-35), with an adult male to adult female sex ratio of 1:0-6-1-3. Subgrouping has been observed. Females form linear dominance hierarchies, but they show relaxed relationships characterized by low levels of intense aggression, bidirectionality when agonistic behavior occurs (either female in a dyad may initiate the interaction), frequent post-conflict affiliative contacts, and an overall high degree of social tolerance (e.g. feeding together). Adult males also show social tolerance as exemplified by low levels of agonistic behavior and frequent grooming interactions. Adult males (typically the highest ranked) emit a birdlike vocalization called a “loud call.” These calls appear to function primarily to influence intragroup cohesion, i.e. to communicate information with regard to location and movement within the social group. Home range size is 45-143 ha, and the ranges of neighboring groups often overlap. Tonkean Macaques are flexible in response to habitat alteration by intensively using particular areas within their home range where known resources are present and predictably available (e.g. A. pinnata palms). Individuals also increase their home range size under such conditions. Mean daily movement is 1175 m. Densities of Tonkean Macaques are 20-67 ind/km? across their distribution.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Overall population size of the Tonkean Macaque is ¢.150,000 individuals. It has the largest distribution of all Sulawesi macaques. It is known to occurin at least three protected areas: Lore Lindu National Park, Morowali Nature Reserve, and Faruhumpenai Nature Reserve, totaling at least 544,000 ha of protected area. Separate conservation management of eastern and western populations of Tonkean Macaques has been suggested, given their genetic distinctiveness. The greatest threat is large-scale conversion of forest for commercial logging and the development of cash-crop plantations, such as oil palm and cacao. Recent reports indicate that 80% of Sulawesi’s forests have been altered and destroyed, and only 30% of the remaining forest is in good condition (i.e. forest canopy unbroken by large clearings and with only scattered signs of human activity). A key concern is that much of the remaining forest is montane (e.g. 90% in Lore Lindu National Park is montane forest ranging up to elevations of 2355 m), and itis not yet certain if forest above 2000 m provides habitat that can sustain Tonkean Macaques throughout the year. Tonkean Macaques are hunted for food in some areas, particularly in non-Muslim areas where consumption of macaques is not taboo. There is also evidence of hunting in Central Sulawesi for local consumption and bushmeat markets in Manado, North Sulawesi. In many areas, and regardless ofreligion, Tonkean Macaques are poisoned or trapped as crop pests. They are also often trapped to sell as pets. Pet ownership is linked to disease transmission between macaques and people. For example, pet Tonkean Macaques from the eastern peninsula of Central Sulawesi showed evidence of exposure (seropositivity for antibodies) to endemic human pathogens, including measles, influenza A, and parainfluenza 1, 2, and 3. The fact that the same human pathogens have been detected in wild populations suggests that pet macaques may act as vectors from human to wild populations because wild macaques are often attracted to pet animals (e.g. when females are receptive), therefore putting wild populations at risk. Human-macaque folklore in the Lindu highlands serves to protect local macaques from retaliation by farmers bacause of crop raiding. It remains unknown, however, at what threshold crop losses will no longer be tolerated, and social taboos, and the conservation outcomes they afford, will be abandoned.

Bibliography. Anderson (1985), Bynum, Bynum, Froehlich & Supriatna (1997), Bynum, Bynum & Supriatna (1997), Bynum, Kohlhaas & Pramono (1999), Cannon et al. (2007), Ducoing & Thierry (2005), Evans, Morales et al. (1999), Evans, Supriatna & Melnick (2001), Fooden (1969), Froehlich & Supriatna (1996), Groves (1980, 2001), Jones-Engel, Engel et al. (2001), Jones-Engel, Schillaci et al. (2005), Juliandi et al. (2009), Kinnaird et al. (1999), Lee, R.J. (1999, 2000), Leighton & Leighton (1983), Masataka & Thierry (1993), Petit & Thierry (1994), Pombo et al. (2004), Riley (2005, 2007a, 2007b, 2008, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c), Riley et al. (2007), Shaifuddin et al. (1993), Thierry (1985, 2000b, 2007, 2011), Thierry, Anderson, Demaria et al. (1994), Thierry, Bynum et al. (2000), Thierry, Demaria et al. (1989), Thierry, Gauthier & Peignot (1990), Ueno & Fujita (1998), Watanabe, Lapasere & Tantu (1991), Watanabe, Matsumura et al. (1991), Zahmianur (2007).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.