Trachypithecus delacouri (Osgood, 1932)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863488 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFBB-FFBF-FFE0-6E73FE27F9AE |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Trachypithecus delacouri |

| status |

|

155. View Plate 52: Cercopithecidae

Delacour’s Langur

Trachypithecus delacouri View in CoL

French: Langur de Delacour / German: Delacour-Langur / Spanish: Langur de Delacour

Other common names: \ White-rumped Black Leaf Monkey

Taxonomy. Pithecus delacouri Osgood, 1932 ,

Hoi Xuan, Vietnam.

1. delacouri was formerly classified as a subspecies of 1. francoisi . It is a member of the Jfrancoisi species group, also known as the karst or limestone langurs. Monotypic.

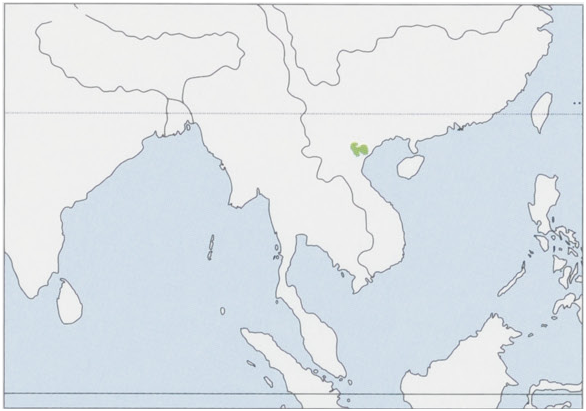

Distribution. NC Vietnam in Hoa Binh, Ha Nam, Ninh Binh and Thanh Hoa provinces. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 52-62 cm (males) and 57-60 cm (females), tail 81-90 cm (males) and 84-89 cm (females); weight 7.5-8.5 kg (males) and 7.3-7.7 kg (females). Black and white body coloration of Delacour’s Langur is unique among the South-eastern Asian langurs. Except for the white pubic patch in females, both sexes have the same pelage color. Pubic patch is formed by an area of unpigmented skin in front of callosities with whitish hairs and has an individually different irregular shape. Black coloration of body is interrupted by a sharply demarcated line in the middle of the back thatis white and extending to a similar line above knees, giving it the appearance of wearing a pair of white “shorts.” Face is black, with elongated grayish-white cheek whiskers stretching from corners of mouth to ears. White hairs reach behind ears where they are numerous and dense and form a white patch. There is a forward-pointing crown crest, and ears stand out from head. The long bushy tail is different from all other Asian langurs. Hairs stick out at right angles from thetail, and fur oftail is bushy and reaches c.10 cm in diameter close to the root so that tail appears carrot-like. Hips of female Delacour’s Langurs occasionally change color from white to yellow or light brown. White hairs on their pubic patch can also change color, which is a result of staining by sweat. Females with babies are especially susceptible to changing color in summer. Delacour’s Langurs are born with a bright yellow-orange pelage—brighter than in the closely related Francois’s Langur (7. francoisi ), the Hatinh Langur (7. hatinhensis ), and the Cat Ba Langur (71. poliocephalus ). Contrasting with these species, bare facial skin of infant Delacour’s Langurs is more yellow. After c.5 weeks from birth, infant hair on hands and feet changes from dark orange to black. After 4-6 months, pelage changes to brownish-black and dark gray shorts become visible, head changes to light brown, and about one-third of tail ends in a tassel. At 9-18 months, pelage changes to black and shorts are light gray. At 18-36 months, body and head change to black and shorts to white, and tail loses the tassel shape and changes to the carrot-like shape, with larger diameter to the root.

Habitat. Broadleaf evergreen forest in typical limestone karst. Delacour’s Langurs occur in areas with steep limestone outcrops. Their occurrence in this harsh substrate is probably for several reasons: to provide shelter for sleeping during cold winter nights and for water sources during a prolonged hot-dry period. In winter, the temperature can drop to 5°C and the temperature inside caves is higher. Water sources are essential. The bowl-like surface of the limestone can store water in small, shadowed, deep valleys for a long period, providing necessary water reserves. Hilly limestone areas without steep outcrops, even undisturbed by humans, are not populated by Delacour’s Langurs, probably because of the absence of surface water and such reservoirs. Delacour’s Langurs occur mostly in lower elevations up to ¢.500 m, and only occasionally higher, up to 1000 m in Pu Luong Nature Reserve. There is no overlap in the distribution of Delacour’s Langurs with other species of the francoisi species group.

Food and Feeding. Delacour’s Langur is among the most folivorous langurs. Leaves make up to 80% of its diet: 60% young leaves and only ¢.20% mature leaves. Unripe fruits (c.10%), shoots, flowers are eaten variably, depending on seasonal availabilities. Preferred leaves have a high protein-to-fiber ratio. Insects or other small animals are not eaten. About 30% of the daily activity budget of Delacour’s Langur is used for feeding. The dietary diversity of Delacour’s Langurs is high relative to the number of plant and tree species used as food, but they do not focus on special limestone plant species. About 60 tree and plant species are used for food in the wild and 137 plant and tree species have been eaten in captivity. An adult individual Delacour’s Langur eats ¢.1100 g/day. They are dependent on water for digestion. Daily water consumption depends on air temperature, amounting to 0-02 ml/g body weight at 25°C and 0-07 ml/g body weight by 32°C.

Breeding. Male Delacour’s Langurs reach reproductive maturity at c.5 years of age, females at four years. The gestation period is 180-196 days. Females give birth to a single offspring. The interbirth interval is 19-25 months. Infants in captivity are weaned at 19-24 months (likely less in the wild).

Activity patterns. Delacour’s Langurs are diurnal, crepuscular, arboreal, and terrestrial. Especially in disturbed areas, groups leave their sleeping sites before dawn and return at dusk or in complete darkness. About 60% of the day is spent resting, 30% feeding, 6% socializing, and 4% traveling.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In limestone areas with prevailing steep cliffs, Delacour’s Langurs spend nearly 80% of the time on rocks. Quadrupedalism is the most frequent form of locomotion on rocks and in trees, more than double that of climbing. Nearly double the amount of time climbing is spent on rocks than on trees. Terrestrialism does not adequately describe their locomotion; they are cliffclimbers. They leap only 6% of the time, much less than other African and Asian colobines. There are differences in frequencies of climbing and leaping between substrates; they leap three times more frequently on trees than on rocks. When leaping between support types, they more frequently use trees as a landing substrate than rocks. During walking, running, and leaping, a concave downward arch of the tail is exhibited, as is found in the northern species of the “limestone langurs,” Francois’s, Cat Ba, and White-headed (7. leucocephalus ) langurs. This tail posture differs from the southern species, the Hatinh, Laos (7. laotum ), and Black (71. ebenus ) langurs. There have been only a few observations regarding home range size because of the threedimensionality of the habitat. Home range sizes are ¢.20-50 ha and depend on the sizes of areas with vegetation and bare rocks. The normal social unit is a polygynous group, with one adult male, several adult females, and their immature offspring. Two males in one group that appear to be adults are probably relatives, brothers or father and son. A group comprises, on average, ten individuals, one adult male, four adult females, two to three subadults and juveniles, and two to three infants. The largest group observed comprised 17 individuals, with one adult male, nine adult females, and their offspring. Subadult males leave their family group and travel alone or form bachelor groups with other males. Up to four individuals can form such a bachelor group. If these males grow to maturity, they try to split females from a group, or to take over a whole group. When replaced, an adult male travels mostly alone. Home ranges of the groups generally overlap, and there are occasional fights between males on the borders. Sometimes females transfer to another group. An area with a few very small groups (e.g. a male with only one or two females) probably testifies to hunting, which hinders the formation of normal social units.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Delacour’s Langur has been listed as one of the “World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates ” since 2000. It is protected by Vietnamese law. Its distribution is highly fragmented and restricted to limestone outcrops. The total distribution comprises ¢.5000 km?, but their area of occurrence is limited to ¢.400 km®. The northern border of the distribution is formed by the Da River, and the southern border is most probably the Ma River. It is questionable whether Delacour’s Langur occurred south of the Ma River in the past. The population of Delacour’s Langur is less than 250 individuals, and it is fragmented into isolated subpopulations. During the 1990s, 19 subpopulations were recorded. After 2000, at least nine were extirpated. Van Long Nature Reserve (Ninh Binh Province) harbors the largest population with more than 100 individuals, ¢.50% of the world’s total number. An estimated group of 30-40 exists in Pu Luong Nature Reserve (Thanh Hoa Province), and about the same number occurs in the unprotected Kim Bang area (Hoa Binh Province). Other subpopulations number less than 20 individuals. Poaching has been the biggest threat in the past. Delacour’s Langurs are prized for use in the preparation of a traditional medicine, “monkey balm.” Increasing limestone quarrying for cement production and building materials is a new threat and is shrinking habitat dramatically. A successful captive breeding program was established at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam, in 1996.

Bibliography. Ebenau (2011), Ebenau et al. (2011), Fooden (1996), Groves (2001), Klein (1999), Kullik (20094, 2009b), Luong Van Hao & Le Trong Dat (2008), Nadler (1994, 1996a, 1996b, 1996¢, 1997, 2004, 2009a, 2010b), Nadler & Streicher (2004), Nadler, Le Trong Dat & Luong Van Hao (2004), Nadler, Le Xuan Canh et al. (2008), Nadler, Momberg et al. (2003), Nadler, Vu Ngoc Thanh et al. (2007), O'Brien (2006), O'Brien et al. (2006), Pham Nhat (2002), Ratajszczak et al. (1990), Stevens et al. (2008), Ulibarri (2006), Workman (2010a, 2010b), Workman & Le Van Dung (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Trachypithecus delacouri

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Pithecus delacouri

| Osgood 1932 |