Simias concolor, G. S. Miller, 1903

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863432 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFA4-FFA2-FA31-69E0F58BFABD |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Simias concolor |

| status |

|

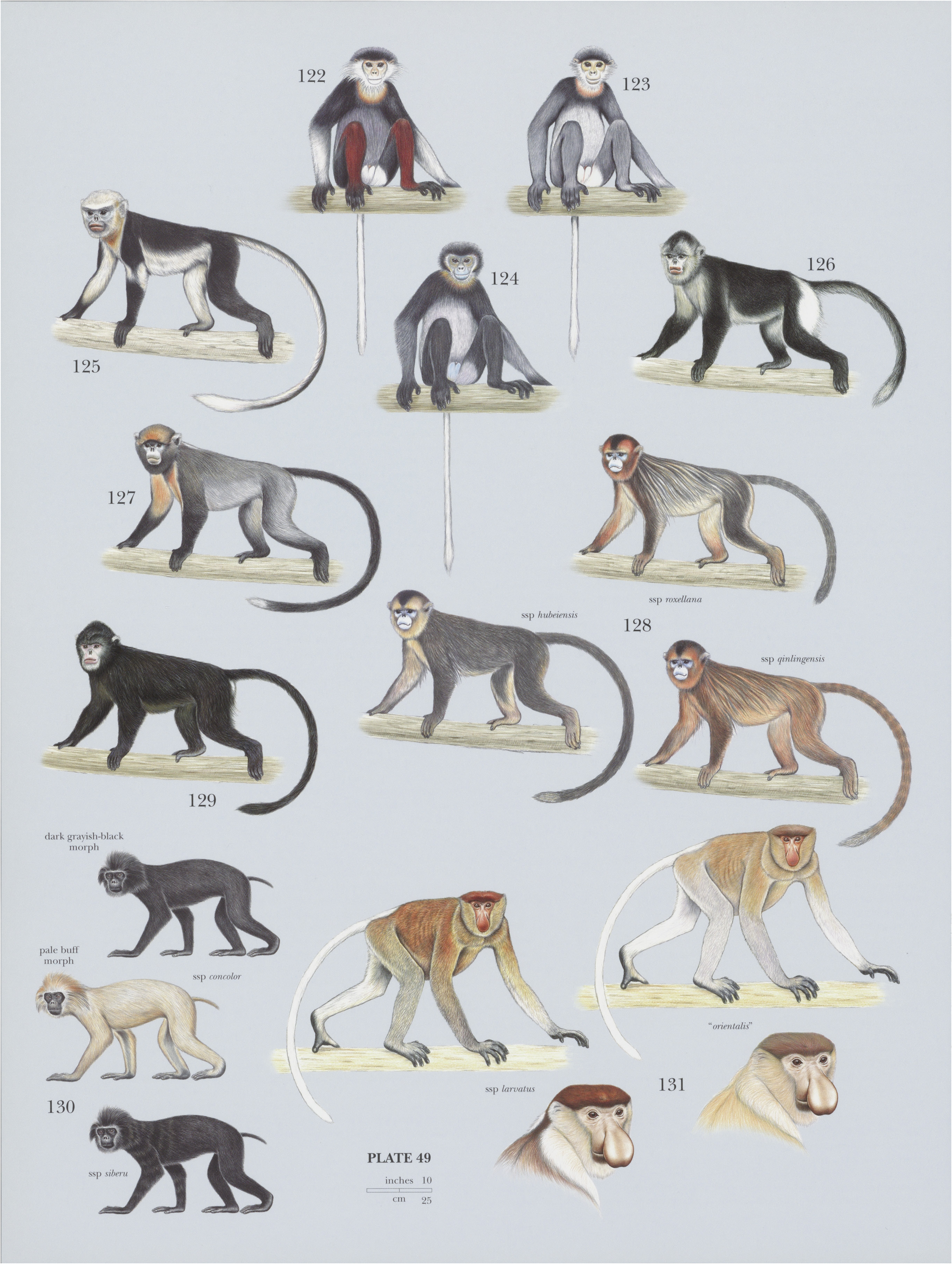

130. View Plate 49: Cercopithecidae

Pig-tailed Langur

French: Langur a queue de cochon / German: Pageh-Stumpfnase / Spanish: Langur de cola de cerdo

Other common names: Mentawai Islands Snub-nosed Langur, Pig-tailed Snub-nosed Langur; Makobu/Siberut Snub-nosed Monkey/Siberut Pig-tailed Langur (siberu), Masepsep / Pagai Pig-tailed Langur / Pig-tailed Snub-nosed Monkey ( concolor

Taxonomy. Simias concolor G. S. Miller, 1903 View in CoL ,

Indonesia, West Sumatra, South Pagai Island.

The Pig-tailed Langur was originally described in its own monotypic genus, Simtas, although some later systematists chose to classify it in the genus Nasalis . Recent genetic data have suggested strongly that the closest relative of Simias is N. larvatus , the Proboscis Monkey of Borneo. Two subspecies recognized.

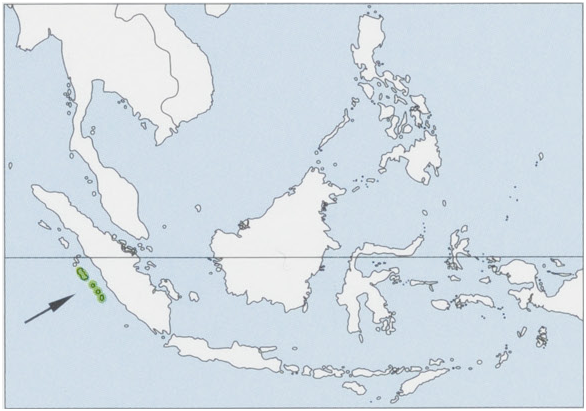

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. c. stberu Chasen & Kloss, 1928 — Mentawai Is (Siberut I). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 49-55 cm (males) and 46-52 cm (females), tail ¢.16 cm (males) and c.14 cm (females); weight 8.5-8.8 kg (males) and 7.7-2 kg (females). Male Pig-tailed Langursare larger and ¢.30% heavier than females, with canines ¢.95% longer in males than females. In both subspecies, there are two distinct color morphs. The first, more common, morph is dark grayish-black, with some agouti banding on anterior parts of the body, a white penal tuft, and a lighter-colored crown. The second morph is a pale buff color; it is somewhat uncommon on Siberut (c.33% of observed individuals in central and southern Siberut and only ¢.5% in northern Siberut) and extremely rare on the Pagai Islands. Both color morphs have white cheek patches and black on face, hands, and feet. The “Pagai Pig-tailed Langur” (S. c. concolor ) is less dark, more brownish-toned, than the “Siberut Pig-tailed Langur” (S. ¢. siberu ). White cheeks on the Siberut Pig-tailed Langur are more conspicuous than on the Pagai Pig-tailed Langur, and its black color (in the dark morph) has more banding on anterior parts. Fur on crown is directed backward, except for a pair of sideways-facing ear tufts. Nasal bone is elongated, but nose itself is snubbed and upturned. Tail is short, upturned, curly, and mostly hairless. The Pig-tailed Languris the only colobine with a short tail. Buttock pads of males are joined in the midline, but they are separated by the urogenital triangle in females. Unlike any other Asian colobine, female Pig-tailed Langurs exhibit sexual swellings, with the urogenital triangle swelling prominently during receptive periods of the menstrual cycle. Front and hind limbs are roughly equal length. Pig-tailed Langurs have a powerful odor.

Habitat. Swamp and lowland rainforest and primary hillside forest in the interior of the islands. Pig-tailed Langurs are sometimes found in mangrove forest but rarely in secondary forest. Mentawai forests are ever-wet with annual rainfall of up to 4000 mm.

Food and Feeding. Pig-tailed Langurs eat mainly leaves, supplemented with fruits, seeds, and flowers. They occasionally raid cacao plantations.

Breeding. Female Pig-tailed Langurs exhibit sexual swellings, but it is questionable whether they are comparable to swellings seen in most species of papionins and Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Breeding appears to be seasonal, with mating in February-August and newborns most commonly seen in June-July. Single births are the norm.

Activity patterns. The Pig-tailed Langur is diurnal, arboreal, and terrestrial. When alarmed by humans, they remain motionless in dense foliage, not making a sound. If threatened further, they drop to the ground and attempt to flee.

Movements, Home range and ‘Social organization. Despite the fact that the limbs of Pig-tailed Langurs are roughly of equal length (suggesting a more terrestrial existence), their movements are mostly through trees. Group travel is initiated by adults of either sex, with no consistent leader, and group members stay within a short distance of each other throughout the day. They tend to move more slowly and quietly than sympatric Presbytis . Males produce loud calls (a series of loud nasal barks), mostly in the early morning but also throughout the day, with another peak in the late afternoon. Females with infants often “park” them in a tree crown while feeding nearby. Groups of Pig-tailed Langurs typically sleep in densely foliated trees in the canopy or in emergent trees. Home range size is variable, depending on their density. In most areas, typical home ranges are c.7-25 ha. Hunting appears to affect group size and social organization by changing densities. Social organization is variable, described as “monandrous,” because the most commonly observed group composition is one adult male and one or more adult females. Multimale—multifemale groups have also been reported, with more adult females than males. Average group size for the Siberut Pig-tailed Langur in northern Siberut (7-9 individuals) is reportedly higher than in other parts of Siberut or for the Pagai Pig-tailed Langur throughout its range (3-4 individuals). Population densities of the Pagai Pig-tailed Langur are ¢.5-21 ind/km? in unlogged forest. The density of the Siberut Pig-tailed Langur is up to 53 ind/km? in the Peleonan Forest in northern Siberut. The Pig-tailed Langur is sympatric with the Siberut Langur ( Presbytis siberu ), the Siberut Macaque ( Macaca siberu ), and Kloss’s Gibbon (Hylobates klossii) on Siberut and with the Mentawai Langur (FP. potenziani ), the Pagai Macaque ( Macaca pagensis ), and Kloss’s Gibbon on the southern Mentawai Islands. Pig-tailed Langurs form mixed-species associations with the Mentawai Langur and the Siberut Langur.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List, including both subspecies. The Pig-tailed Langur is protected by Indonesian law. They are remarkably little known or studied; indeed, up until the late 1970s, they had not even been photographed. They are threatened mainly by hunting for meat, commercial logging, conversion of their habitat into oil palm plantations, and forest clearing by local people. While all Mentawai primates are hunted, Pig-tailed Langurs are preferred prey in all areas. Recently, hunting has increased because of improved access to remote areas due to logging roads and tracks, replacement of bows and arrows with rifles, and changes in local rituals and taboos that formerly regulated hunting. Pig-tailed Langurs are sometimes taken for the pet trade, but they rarely, if ever, thrive. They are also occasionally poisoned as agricultural pests. All of these factors have resulted in a significant decline in their numbers and even their total elimination on some islands that they formerly occupied. The Siberut Pig-tailed Langur has the largest remaining population of 6000-15,500 individuals, estimated in 2006. The Pagai Pig-tailed Languris in urgent need of protective measures, with a total population estimated at just 700-1800 in 2006. The most recent estimate of total population size for the Pig-tailed Langur was 6700-17,300 in 2006, representing a decline of 73-90% since a 1994 estimate. It is known to occur in only one protected area (Siberut National Park), butit also occurs in the proposed Betumonga Research Area on North Pagai (recently reported to have been logged over). It is found at its highest density in the Peleonan Forest in northern Siberut, which, as of 2011, is protected on a short-term basis by local agreements to exclude logging concessions. In 2006, the following conservation actions were suggested: increased protection for Siberut National Park, which currently lacks enforcement; formal protection of the Peleonan Forest in North Siberut, which has an unusually large primate population and is easily accessible; protection of areas in the Pagai Islands by cooperating with a logging corporation that has practiced sustainable logging techniques since 1971; conservation education, especially regarding hunting; and the development of alternative economic models for local people to reduce the likelihood of them selling off their lands to logging companies.

Bibliography. Brandon-Jones et al. (2004), Chasen & Kloss (1927), Fuentes (2002), Fuentes & Tenaza (1995), Groves (1989, 2001), Hadi et al. (2009), Liedigk et al. (2012), Miller (1903), Mitchell & Tilson (1986), Paciulli (2004, 2011), Quinten et al. (2010), Roos et al. (2011), Tenaza (1987, 1989a, 1989b), Tenaza & Fuentes (1995), Tilson (1977), Watanabe (1981), Whittaker (2006), Whittaker & Mittermeier (2008), Whittaker et al. (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.