Dinotoperla walkeri, Dean, John & Clair, Ros St, 2006

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.172724 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6256916 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CC54EC7E-C307-8708-3873-FECDFAFBE573 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Dinotoperla walkeri |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Dinotoperla walkeri View in CoL sp. nov.

(Figs 1–10)

Material examined

Holotype: Male, Victoria, Hopkins River, Hopkins Falls, 38 20’S 142 33’E, 28 Oct. 2004, J. Dean & R. St Clair, Museum of Victoria (MV), T18675.

Paratypes: 8 males (MV, T1867618683), 8 females (MV, T1868418691), 8 terminal instar nymphs (MV, T1869218699), all collected with holotype; 8 males, 8 females, 8 nymphs, all collected with holotype (Australian National Insect Collection). Other material examined: 19 males, 13 females, 11 nymphs, all collected with holotype (EPA Victoria collection); 1 male, 1 female, 1 nymph, all collected with holotype (G. Theischinger collection); Hopkins River, Hopkins Falls: 11 nymphs, 17 Oct. 1995; 1 nymph, 18 Oct. 2004; 12 males, 9 females, 17 nymphs, 24 Oct. 2005 (EPA Victoria collection).

Diagnosis

Robust habitus. Both sexes brachypterous, wings as long as respective nota. Antennae relatively short, robust, segments at midlength about 1.5x as long as wide. Cerci short, 9–10 segments. Epiproct in lateral view strongly arched, apically down turned and terminating in a single point.

Adult male. Robust. General colour dark brown, almost black. Antennae robust, about as long as combined length of head and thorax, segments at midlength about 1.5x as long as wide. Pronotum (Fig. 1) uniformly dark; slightly wider than long, posterior margin wider than anterior margin, the latter convex; corners rounded; moderate depression on either side of midline in anterior third, shallow transverse depression a little in front of posterior margin; area between depressions with series of slightly raised irregular surfaces. Wings brachypterous, forewing and hindwing about the same length as respective nota (Fig. 1). Legs dark brown, femora with two darker longitudinal lines, tibiae with one darker longitudinal line, as described and figured for the nymph ( Fig. 10 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ). Genitalia with central sclerite of tergite X membranous, lateral margins parallel, posterior margin ranging from broadly convex to somewhat triangular but with apex rounded (Fig. 2), in lateral view produced as broadbased membranous cone (Fig. 3); epiproct in lateral view strongly arched, dorsal margin gently curved or sometimes slightly flattened, apically down turned and terminating in acute point, ventral margin with broad semicircular concavity in distal half, with series of small ventral spicules towards apex (Figs 3, 4, 6); paraprocts with base rather wide, lobe slender, in lateral view narrowing gradually to apex, terminating in upturned sclerotised point, outer surface with longitudinal sclerotised band (Figs 3, 4). Cerci short, 9–10 segments.

Adult female. Robust. Body colour similar to male. Subgenital plate with posterior margin relatively straight, sometimes weakly convex or concave, not protruding over sternite nine ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ); posterior margin of tergite 10 angular, apex narrowly rounded ( Fig. 7 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ); paraprocts subtriangular, moderately long and broad ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ). Cerci short, 9–10 segments.

Mature nymph ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ). Robust. Body colour dark brown, almost black. Antennae short and robust, length approximately equal to combined length of head and thorax; 34–39 segments; segment width approximately equal to length at mid length of antenna. Pronotum wider than long, anterior and posterior margins convex, corners broadly rounded; colour dark brown, with mottled pattern of small darker spots; setae inconspicuous. Meso and metanotum dark brown with conspicuous pale knoblike boss near the base of all four wing pads, which are extremely abbreviated. Legs ( Fig. 10 View FIGURES 7 – 10 ) robust; colour dark brown, femora with longitudinal darker band near outer margin and usually with less distinct dark band near inner margin, dark longitudinal band on tibiae; outer margins of femora and tibiae with dense fringe of long setae, less dense series of shorter setae on tarsi. Abdomen dark brown with four small dark spots spaced across each segment; tergum 10 densely covered with simple setae, which are pale and inconspicuous; posterior margin of tergite 10 rounded in female, angular with strong mesal elevation in male. Cerci short, only about as long as last three abdominal segments; 14–18 segments; length of individual segments about 3–4 times width at midlength of cercus.

Etymology

The species is named after Dr. Ken Walker of the Museum of Victoria, in appreciation of the many years of friendship and cheerful assistance he has provided to us and to students of aquatic insects in general. The name walkeri also seems appropriate for a stonefly which cannot fly.

Remarks

Adults of D. walkeri are distinguished by large size, robust antennae, brachyptery and the distinctive form of the male genitalia. They appear to be most similar to D. thwaitesi Kimmins , but D. thwaitesi is distinguished by the less robust body, the long, slender antennae with elongate segments (length 3– 4 x width), the larger number of cercal segments, and in the male the narrower central sclerite of tergum X and the less strongly arched epiproct.

The nymph of Dinotoperla walkeri appears to be most closely related to D. serricauda Kimmins and D. thwaitesi . Shared nymphal characters include the distinctive mottled pattern on the pronotum, strongly developed bosses on the mesonotum and metanotum, longitudinal dark bands on all femora and tibia, a characteristic series of dark spots on the abdominal terga and cerci considerably shorter than the abdomen. It is distinguished from these two species in the nymph by the large size, the shorter robust antennae, the fewer cercal segments and the absence of developing wing pads.

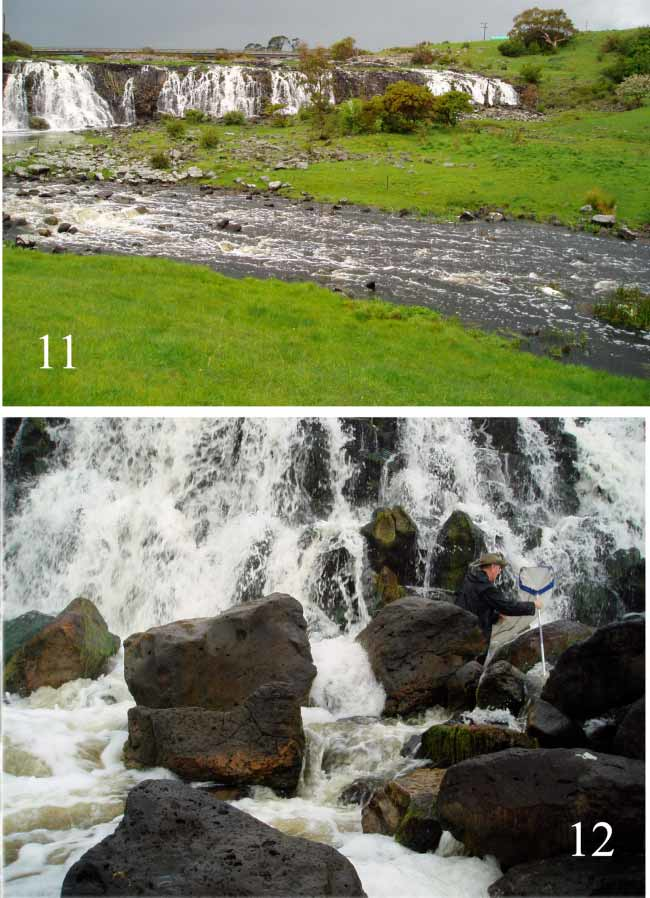

Nymphs of D. walkeri have been collected in routine kick samples from boulder dominated substrates in fast current, approximately 100 metres downstream from the main falls, and also at the base of the falls ( Figs. 11, 12 View FIGURES 11 – 12 ). The type series of adults was collected on large, emergent boulders surrounded by fast flowing water. Individuals were cryptic, forming dense aggregations in the narrow crevices where one boulder rested against another. An intensive attempt to collect additional specimens in March 2005 was unsuccessful. Furthermore, nymphs were absent from routine autumn samples collected in March1994 and March 1995. This raises the possibility that egg hatching and recruitment is delayed until later in autumn, and that nymphs grow rapidly to emerge as adults in spring. The Hopkins River is organically enriched, and such a life history would enable nymphs to avoid potentially unfavourable conditions over the summer period.

It is not uncommon in the order Plecoptera for wings to be absent (aptery) or shortened (brachyptery). Lencioni (2004) regarded brachyptery as an adaptation to very cold environments, either high altitude or high latitude, and suggested it was either a response to temperature being too low to enable flight or a response to the presence of strong winds which prevented directional flight. In Australia the gripopterygid stoneflies Leptoperla cacuminis Hynes and Riekoperla darlingtoni (Illies) are wingless, while brachypterous populations or individuals have been reported for Eusthenia venosa brachyptera (Tillyard) (Eustheniidae) , Leptoperla kallistae Hynes , Leptoperla varia Kimmins , Riekoperla isosceles Theischinger , Riekoperla cornuta Theischinger , Riekoperla intermedia Theischinger , Dinotoperla hirsuta McLellan , Eunotoperla kershawi Tillyard (Gripopterygidae) , Austrocercella illiesi Theischinger and Notonemoura lynchi Illies (Notonemouridae) ( Hynes 1974; Theischinger & Cardale1987; Michaelis & Yule 1988). While most of these are alpine species, some are found well below the tree line. The Australian alps are of relatively low altitude, and during adult flight periods temperature and wind conditions are probably more benign than those considered by Lencioni (2004). Many fully winged populations and species occur over a broad range of altitudes, including above the tree line. This suggests that factors other than low temperatures and high winds may be responsible for brachyptery in Australian stoneflies. Dinotoperla walkeri , Leptoperla cacuminis , a truly alpine species, and Riekoperla darlingtoni , from below the treeline appear to be the only species in Australia in which all individuals are unable to fly. The reasons for this are unknown. The repression of flight can be considered energy efficient, allowing energy to be redirected to other activities such as egg production, but this has to be balanced against a loss of mobility and dispersal ability.

Hopkins Falls, the type locality of Dinotoperla walkeri , is located on the western volcanic plains of Victoria, a little more than 10 km from the coast at an altitude of about 20 metres above sea level. The climate is relatively mild, although the region is often exposed to strong winds. The lowest water temperature recorded during routine biological monitoring has been 13 C. The nymphal habitat appears to be localised.

Riffles are rare in the district, and those we did locate and sample were much slower or lacked the very large boulders of the Hopkins Falls site. Riffles in Mt Emu Creek and the Hopkins River upstream of the junction with Mt Emu Creek yielded D. thwaitesi but not D. walkeri , while a riffle in the Merri River did not yield any stoneflies.

This suggests to us that development of brachyptery in D. walkeri could be strongly adaptive. Emerging adults have to lay eggs in or close to suitable nymphal habitat, and if adults were winged they could be dispersed by wind (or by choice) and subsequently be unable to relocate the only suitable oviposition site for many kilometres. This contrasts with the situation in D. thwaitesi , which appears to coexist with D. walkeri in the torrential habitats at Hopkins Falls. However, because D. thwaitesi also occurs at slower current speeds, suitable habitat is available in both upstream and downstream reaches, and the possession of wings represents an advantage rather than a liability.

If a strongly localised distribution of D. walkeri is confirmed, this raises concerns for the conservation status and survival of the species. There is an obvious need for further investigation of the biology and distribution of Dinotoperla walkeri in the Hopkins River.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |