Valimia Gustafsson, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4801.3.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CD99A07C-2C32-48A5-9EF8-769004715644 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/C770FA5E-FFE1-FF8D-6681-966110F784DE |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Valimia Gustafsson |

| status |

|

Valimia Gustafsson & Zou, new genus

Type species. Oxylipeurus corpulentus Clay, 1938 .

Diagnosis. Morphologically, within the Oxylipeurus -complex, Valimia belongs to the same group as Reticulipeurus , Cataphractomimus and Sinolipeurus . This group is characterised by relatively large bodies, rounded preantennal heads without median extensions, and extensive reticulation on most of the body (variable among species in Reticulipeurus ; Gustafsson et al. 2020). The presence of a dorsal preantennal suture in Reticulipeurus separates species of this genus from those of the other three genera. Valimia can be separated from both Cataphractomimus and Sinolipeurus by the following characters: (1) male tergopleurites IX+X and XI fused in Valimia ( Figs 1 View FIGURES 1–2 , 12 View FIGURES 12–13 , 21 View FIGURES 21–22 ), but separate in the other two genera (see figs 3–4, 19– 20 in Gustafsson et al. 2020); (2) male temples with distinct ventral inner carina and intense reticulation of ventral surface of eye and area between marginal temporal carina and inner carina in Valimia ( Figs 5 View FIGURES 5–10 , 16 View FIGURES 16–20 , 25 View FIGURES 25–29 ), but without this structure in the two other genera (see figs 3–4, 19– 20 in Gustafsson et al. 2020).

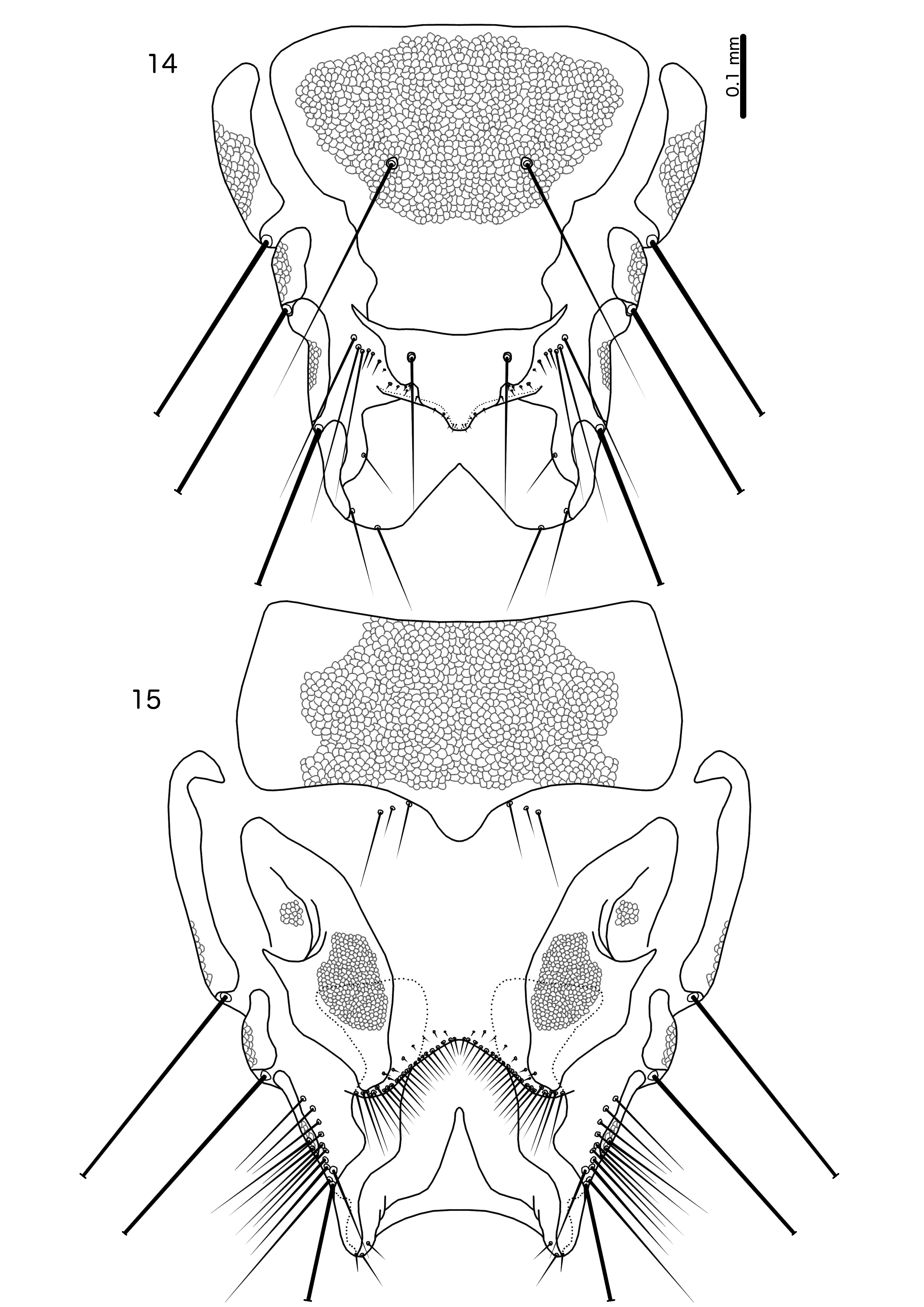

In addition, Valimia can be separated from Cataphractomimus by the following characters: (1) male subgenital plate in Cataphractomimus either separate from sternal plate VIII or with lateral margins deeply incised and sternal plate VIII continuous with subgenital plate only medianly (see figs 3–4 in Gustafsson et al. 2020), whereas in Valimia the male subgenital plate is completely fused to sternal plate VIII, with no significant lateral incisions ( Figs 3 View FIGURES 3–4 , 14 View FIGURES 14–15 , 23 View FIGURES 23–24 ); (2) stylus of male subgenital plate longer than wide and gently tapered distally in Cataphractomimus (see figs 3–4 in Gustafsson et al. 2020), but short and stout in Valimia ( Figs 3 View FIGURES 3–4 , 14 View FIGURES 14–15 , 23 View FIGURES 23–24 ); (3) pterothorax with distinct postero-lateral horn-like extension in Cataphractomimus (see figs 3–4 in Gustafsson et al. 2020), but without such extension in Valimia ( Figs 1–2 View FIGURES 1–2 , 12–13 View FIGURES 12–13 , 21–22 View FIGURES 21–22 ); (4) female vulval plate medianly continuous, with lateral accessory vulval plates in Cataphractomimus (see fig. 69 in Gustafsson et al. 2020), but medianly separate and without such plates in Valimia ( Figs 4 View FIGURES 3–4 , 15 View FIGURES 14–15 , 24 View FIGURES 23–24 ); (5) male genitalia variable in species of Valimia , but with the mesosome longer than wide, with a complex gonopore that may look different in everted and non-everted specimens but not extending beyond the distal margin of mesosome ( Figs 9–10 View FIGURES 5–10 ), whereas the mesosome of the known species of Cataphractomimus is wider than long, with a simple gonopore that extends beyond the distal margin of mesosome (see figs 35, 38, 41 in Gustafsson et al. 2020).

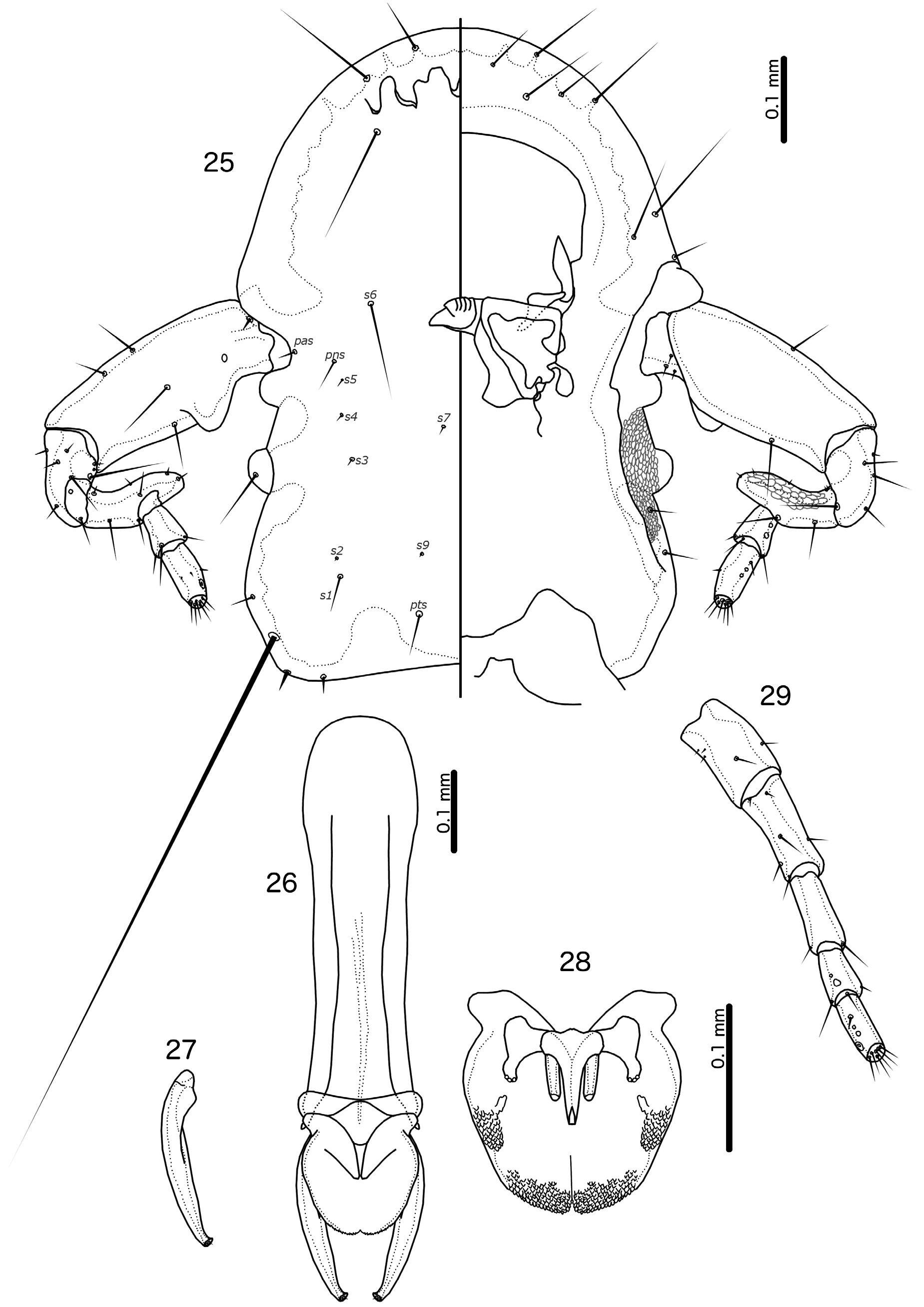

Moreover, males of Valimia can be separated from those of Sinolipeurus by the following characters: (1) reticulation clear and extensive across the dorsal side of the thorax and abdomen in Valimia ( Figs 1 View FIGURES 1–2 , 12 View FIGURES 12–13 , 21 View FIGURES 21–22 ), but very weak in Sinolipeurus (see figs 19–20 in Gustafsson et al. 2020); (2) stylus of male subgenital plate arising terminally, short and stout in Valimia ( Figs 3 View FIGURES 3–4 , 14 View FIGURES 14–15 , 23 View FIGURES 23–24 ), but arising centrally, long and slender in Sinolipeurus (see figs 86–87 in Gustafsson et al. 2020); (3) male genitalia with mesosome longer than broad and with deeply concave anterior margin in Valimia ( Figs 9–10 View FIGURES 5–10 ), but broader than long and with trapezoidal anterior extension in Sinolipeurus (see figs 65, 68 in Gustafsson et al. 2020); (4) male genitalia with the gonopore not reaching the distal margin of mesosome, with the median section generally narrow, and no recurved lateral extensions in Valimia ( Figs 9–10 View FIGURES 5–10 ), whereas in Sinolipeurus the gonopore reaches the distal margin of the mesosome, the median section is broad, and there is at least one recurved extension laterally on each side (see figs 65, 68 in Gustafsson et al. 2020); (5) male genitalia with laterally projecting rugose nodi present in Sinolipeurus (see figs 65, 68 in Gustafsson et al. 2020), but absent in Valimia (the lateral rugose nodi of V. necopinata do not project beyond the margins of the mesosome, Fig. 28 View FIGURES 25–29 ). At present, females of these two genera cannot be compared because those of Sinolipeurus are still unknown.

Description. Both sexes. Head elongated, frons rounded. Marginal and ventral carinae uninterrupted. Dorsal preantennal and dorsal postantennal sutures absent. Internal sclerotization present medianly. Head chaetotaxy as in Fig. X; as3 dorsal; mds present as microsetae in V. corpulenta , not visible in the other two species; pos and mts1 clearly ventral in males of all three species and females of V. necopinata and V. polytrapezia , but dorsal in females of V. corpulenta . Dorsal post-antennal head chaetotaxy varying slightly between species: pas, pns, pts, s1–2, s5–7, s9 present in at least males of all examined species. Smaller sensilla not visible in females, and may be absent; setose sensilla like s1 typically shorter in females than in males. Antennae sexually dimorphic.

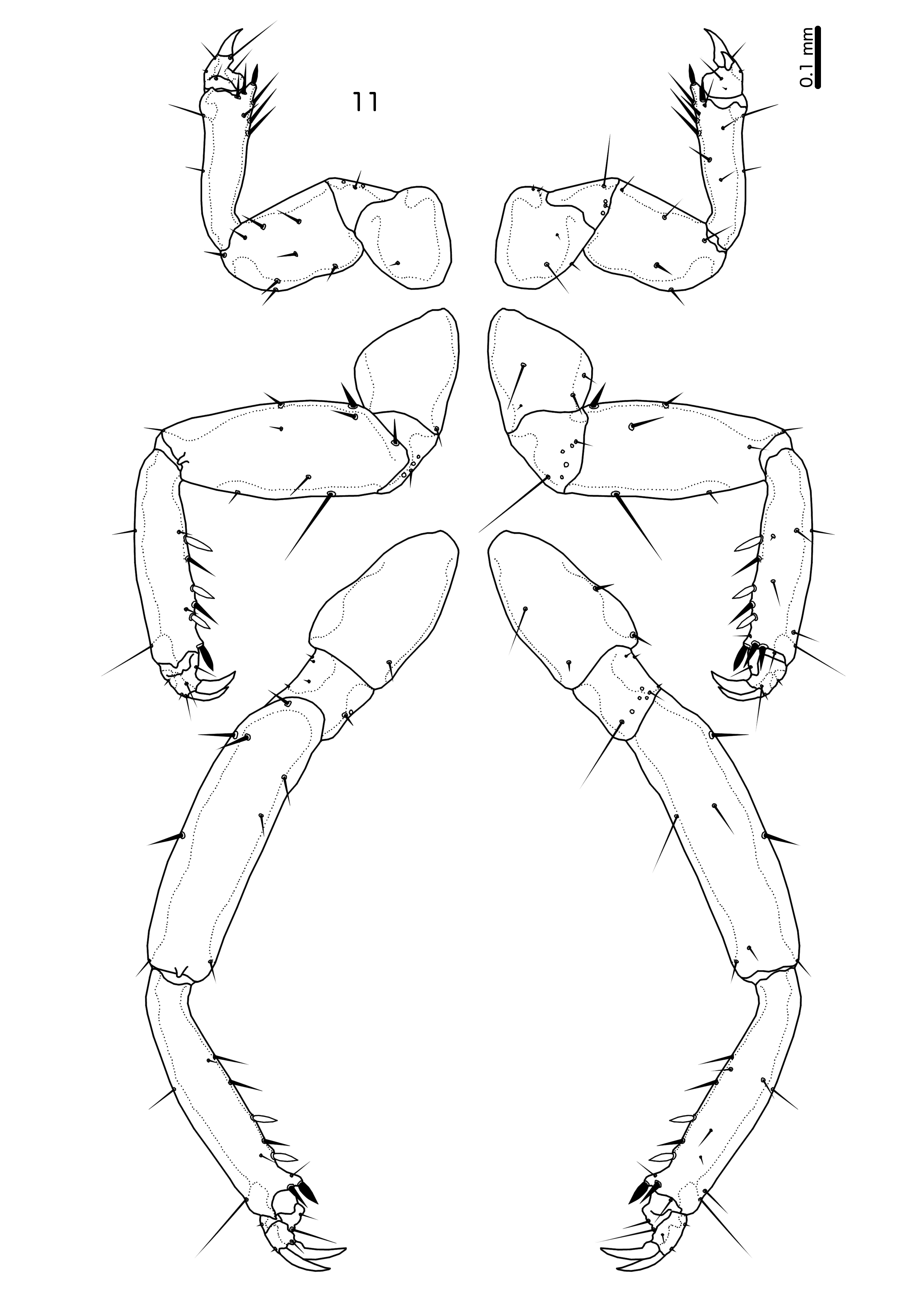

Pro- and pteronotum with at least partial strong reticulation. Pterothorax not extended postero-laterally into horns. Pronotum with 1 dorsal anterior seta, 1 pronotal marginal-lateral seta, and 1 pronotal post-spiracular seta on each side. Pteronotum with 1 anterior and 1 posterior submarginal meso-metathoracic seta, 1 pterothoracic trichoid seta, 1 pterothoracic thorn-like seta, and 4 marginal pterothoracic setae on each side; the marginal setae separated into two discrete clusters on each side. Proepimera with detached postero-median plate on which one seta is situated; in some specimens this detached plate is connected to the main proepimera by an ill-defined, poorly sclerotised section. Metepisternum with median extensions in posterior half that protrude interior to meso-mestasternum. All tergopleurites and sternal and subgenital plates of both sexes with extensive reticulation. Tergopleurites II–VIII medianly separated in both sexes. Chaetotaxy of legs as in Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 .

Male. Temples unique within the Oxylipeurus -complex, with inner carina running from near site of mts3 to antennal socket; area between inner carina and lateral margin of head seemingly slanted, densely reticulated. Eye with ommatidium visible only dorsally, and ventral surface covered by reticulated continuation of ventral head surface. Antennae with swollen and elongated scape and curved and swollen pedicel. Scape with distinct “thumb” in proximal half. Flagellomere I with distinct finger in distal end ( Figs 5 View FIGURES 5–10 , 16 View FIGURES 16–20 , 25 View FIGURES 25–29 ).

Tergopleurites IX+X and XI fused, and medianly continuous. Sternal plate VII separated from subgenital plate, which is formed from sternal plates VIII–IX+X only. No significant lateral incisions of subgenital plate. Lateral accessory plates absent. Stylus short and stout, may not reach distal margin of abdomen ( Figs 3 View FIGURES 3–4 , 14 View FIGURES 14–15 , 23 View FIGURES 23–24 ). Male genitalia differing slightly among species. Mesosome always longer than wide, with extensive rugose areas in distal end and along lateral margins (forming two different rugose areas in V. necopinata , Fig. 28 View FIGURES 25–29 ). Gonopore complicated, with lateral extensions varying between species; gonopore does not reaches the distal margin of mesosome, but may approach it in everted genitalia ( Figs 9–10 View FIGURES 5–10 ). Everted mesosome laterally compressed distally, which changes the outline and the shape of the distal margin ( Figs 9–10 View FIGURES 5–10 ). Parameres differ among species.

Female. Head temples without inner carina, but with extensive reticulated area on ventral head; eyes typically without reticulated area, and ommatidium visible also ventrally. Antennae simple, without enlarged scape or swelling on flagellomere I ( Figs 6 View FIGURES 5–10 , 20 View FIGURES 16–20 , 29 View FIGURES 25–29 ). Tergopleurites IX+X fused medianly, but separated from tergopleurite XI ( Figs 2 View FIGURES 1–2 , 13 View FIGURES 12–13 , 22 View FIGURES 21–22 ). Subgenital plate divided into large anterior plate which may extend distally along midline, and distal lateral plates which are separated medianly. Lateral accessory vulval plates absent. Subvulval plates present, extending anterior to vulval margin.

Host distribution. Currently, all the species recognised as belonging to Valimia in this paper are known from two species of turkeys ( Galliformes : Phasianidae : Meleagris ) (see below). However, if the species discussed below after “Included species” were transferred to Valimia as a result of a revision, the host distribution of Valimia species would also cover members of the family Cracidae (Galliformes) .

Geographical distribution. It is most likely that this genus is found throughout the native ranges of the two host species in North and Central America. It is also found on domesticated birds outside the native host ranges (for records of lice collected on domesticated birds see Table 1).

Etymology. Valimia is named in honour of Dr Michel Paiva Valim (formerly from the Museu de Zoologia of the University of São Paulo, Brazil), in recognition of his substantial contributions to chewing louse taxonomy, morphology, and classification. Gender: feminine.

Remarks. We examined the same specimens studied by Clay (1938), including most of the paratype series of O. corpulentus , and we realised that the lice taken from one host individual of Meleagris gallopavo merriami included three morphologically different species. Two louse species were already named, which we now identified as Valimia corpulenta and V. polytrapezia , whereas the third was an undescribed and unnamed species. These samples had also been examined by Kéler (1958). Therefore, the presence of a third, yet undetected, species within this material was doubly unanticipated.

Although males and females in this sample can be tentatively divided into three possible groups based on morphology, there is no certain way to determine which female belongs to which male from their morphology alone. For instance, males of Valimia polytrapezia can be differentiated by their flat lateral margins of the temples, but none of the three female morphotypes have flat temporal margins. There is also a large degree of overlap in size between the three female morphotypes ( Table 2), and the dorsal postantennal chaetotaxy differs between sexes (see above).

Therefore, we have used the relative extent and pattern of intense reticulation of the thoracic segments to pair up males and females.As a result, the female paratypes of Oxylipeurus corpulenta remained with the male paratypes of this species, but the non-type specimens identified and labelled by Clay (1938) as “ Oxylipeurus polytrapezius polytrapezius ” are here identified as a mixture of Valimia polytrapezia and V. necopinata . Pairing of males and females based on their thoracic reticulation means that both males and females of V. necopinata are more numerous than those of V. polytrapezia . However, genetic data will be required to clearly establish which female morphotype belongs to which species, now based on males.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.