Lucasium iris, Vanderduys & Hoskin & Kutt & Wright & Zozaya, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4877.2.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D2155D37-CB4A-43DB-8593-684179AFFF39 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4576629 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD5A87ED-B21F-FF9E-FF26-E80CFE37DEFB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Lucasium iris |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Lucasium iris sp. nov.

Gilbert Ground Gecko

( Figures 3–6 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 )

Holotype: QM J96406 View Materials , female, Gilberton Station, c. 100 km south of Georgetown, north Queensland, Australia (143°40’ E, 19°12’ S), collected by S.M. Zozaya, 9 April 2018. Paratypes: all collected within 4 km of the above location: QM J88147 View Materials , subadult male collected by A. Kutt and E. Vanderduys, 12 October 2008; QM J95526 View Materials , female collected by J.M. Wright and E. Vanderduys, 7 June 2015; QM J96407 View Materials , male collected by S.M. Zozaya, 9 April 2018. None of the pre-existing specimens of Lucasium or Diplodactylus vittatus held at the Queensland Museum resembled L. iris sp. nov.

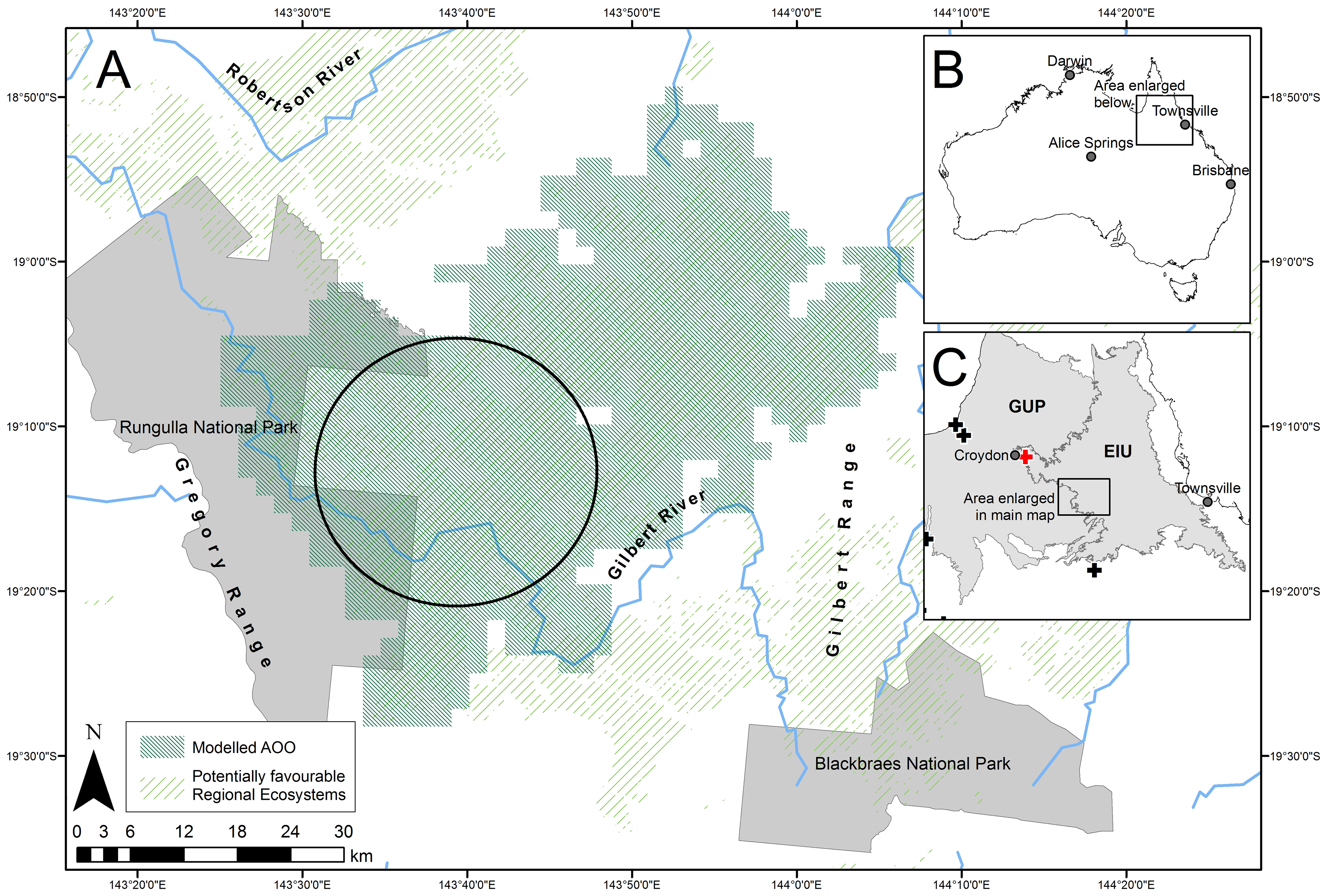

Diagnosis. Lucasium iris sp. nov. is a large (adult SVL range 53.7–62.8 mm) Lucasium from central north Queensland, Australia ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). Lucasium iris sp. nov. is morphologically distinct from all other Lucasium and easily distinguished from congeners by the following set of characters: large size; moderately long and narrow tail (TL/SVL 0.73–0.79; TW/TL 0.10–0.11); nares in contact with rostral scale; dorsal and lateral body scales homogeneous; pattern consisting of a broad pale vertebral stripe running from the snout to the base of the tail, and bordered laterally by small pale spots; paired, enlarged apical lamellae present under all digits. Characters separating Lucasium iris sp. nov. from each Lucasium species and Diplodactylus vittatus Gray, 1832 , to which it can look similar, are provided below in ‘Comparison with other species.’

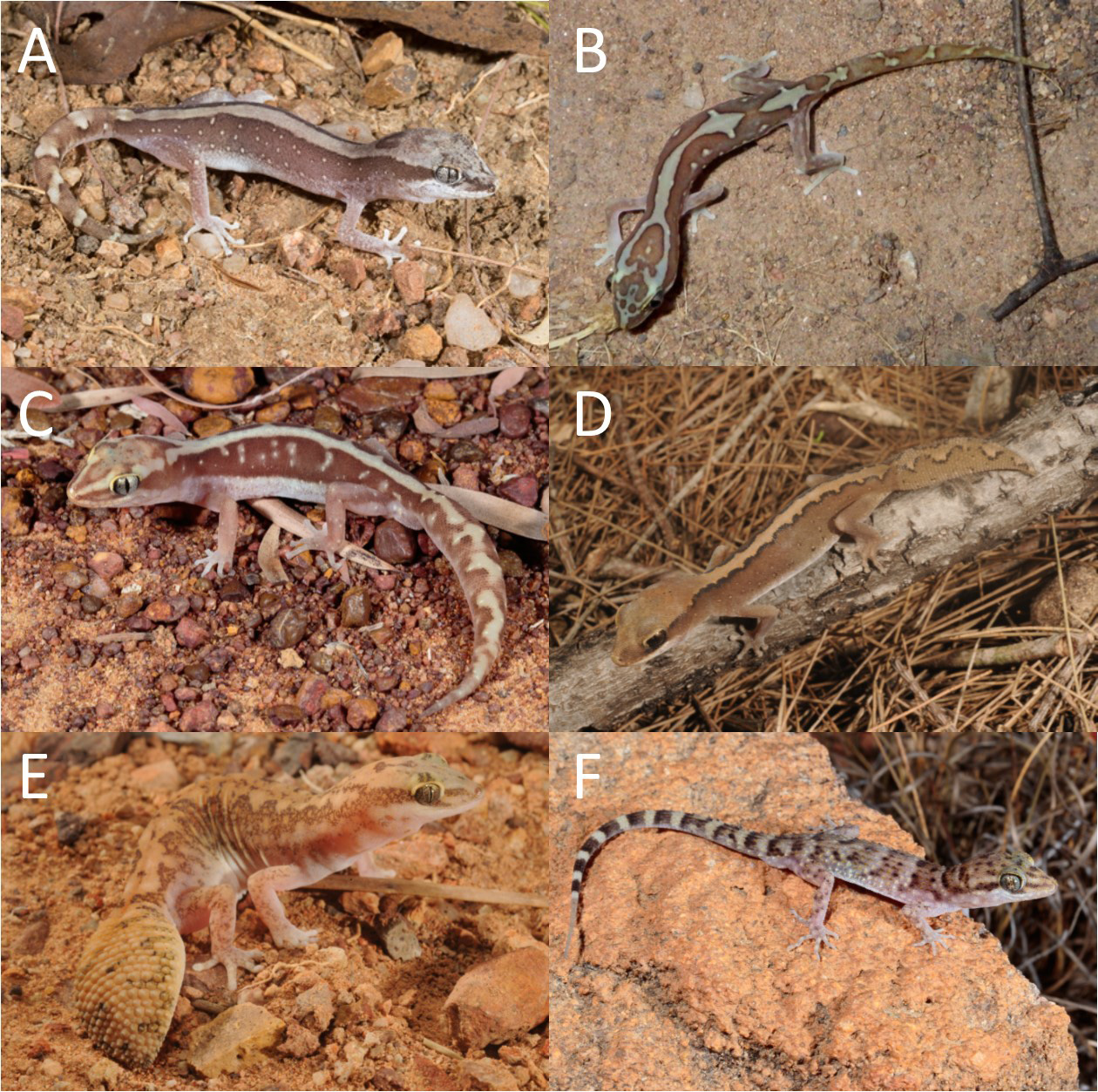

Description. Holotype ( Figures 3A View FIGURE 3 , 4 View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 ): Details of morphometrics and scalation are presented in Table 1 View TABLE 1 .

Morphology: head distinct from neck. Snout rounded when viewed from above and from the side. Pupil vertical. Ear opening round. Trunk robust, c. 0.44 of the SVL. Limbs long and slender. Tail completely original; tapering gradually.

Scalation: rostral scale rectangular, c. 2.5 times wider than deep, contacting the nares. Rostral with a medial crease 45% of its depth. Rostral bordered above by two enlarged internasal scales and these bordered above by three scales: two enlarged and one medial, slightly smaller, approximately hexagonal scale. Infralabial scales wider and deeper than supralabials; both arrays becoming progressively smaller towards the hinge of the jaw. Mental scale 1.2 times wider than long and would be an acute isosceles trapezoid, except for slightly concave sides where it contacts the first supralabial; bordered posteriorly by two slightly enlarged postmentals. General head and body scalation of small rounded granular scales; slightly larger on the throat and belly than dorsal surfaces, but otherwise approximately equal. Limb scalation similar to body scalation. Tail original, roughly cylindrical in cross section. Behind level of vent, tail scales arranged in c. 180 annuli, becoming disorganised a few scales from the tail tip. Tail scales otherwise similar to body scales. Scales on underside of all digits slightly enlarged and protuberant compared to adjacent scales; c. 14 from base of each 4 th toe to tip, but not including enlarged apical lamellae.

Colour in life ( Figures 3A View FIGURE 3 , 4 View FIGURE 4 ): Prominent cream to beige vertebral stripe from neck to base of tail, bordered by rich chocolate brown, fading laterally, c. 13–21 scales in width. Vertebral stripe has a discontinuous faint medial peppering of reddish-brown scales, and a patch of similarly coloured scales medially on the back of the head. An- teriorly, vertebral stripe expands to form a broad, pale crown over the top of the head, narrowing to a point at the nares, and bordered laterally by a distinct, broad, dark temporal and loreal stripe, which is a continuation of the dark dorsolateral ground colour. A scattering of small, pale, cream to lemon spots adjacent to the pale vertebral stripe, each typically occupying 2–4 scales, becoming inconspicuous on the lateral surfaces of the body. Brown dorsal colour fades towards the belly. Posteriorly, pale vertebral stripe continues onto tail base, becoming tinged with yellow just anterior to the vent; tail colour otherwise similar to trunk colour but with yellow tinge dorsally and laterally. Solid vertebral stripe becomes a broad messy, broken zigzag on tail, fading to poorly contrasting bands towards tail tip. Eye colour pale blue to silver, finely speckled with dark spots and with numerous brown to black reticulations. Supralabial scales peppered with minute very dark grey to black spots, usually encompassed by a pale ring separating them from a faint lemon background. Infralabials similar but less spotted anteriorly. Scales bordering upper half of eye tinged yellow. Limbs paler than dorsum, hind limbs with faint small spots. Belly, throat, undersides of legs, and tail immaculate. Feet and toes white; undersides of 3 rd and 4 th toes on hindlimbs tinged pale brown. Mouth lining pink.

Colour and pattern in preservative ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ): Pattern as in life. Colour similar to that in life but slightly faded. All traces of lemon and yellow colouration visible in life are lost.

Paratypes. See Table 1 View TABLE 1 for morphometric and scalation data. Paratypes are very similar to the holotype, except that QM J96407 View Materials is a male and possesses a pair of precloacal pores. QM J88147 View Materials is substantially smaller than the other specimens, and appears to be a subadult, though we did not examine it internally for gonadal maturity .

Colour in life ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 B–D): Dorsal colouration very similar to holotype, varying in number of pale spots on the lateral surfaces adjacent to the vertebral stripe. Spots more variable in size in QM J96407 View Materials and QM J95526 View Materials , occupying 1–9 scales. Cloacal spurs pale lemon surrounded by an irregular ring of darker scales in QM J96407 View Materials . Tail of QM J96407 View Materials similar to holotype, but with less consistent continuation of the vertebral stripe. Tail of QM J95526 View Materials mostly lacking consistent dorsal stripe, the pattern being broken into irregular blotches. Some dark speckling within the vertebral stripe in QM J95526 View Materials . Colouration on lateral surfaces not fading as markedly in paratypes as in holotype, resulting in a greater contrast between the upper and lower flanks. Colouration of the belly, throat, and lower limbs similar to holotype. Irregular dark speckling on top of head more prominent on paratypes than holotype. Eye colour similar to holotype. Labial spots brown on QM J95526 View Materials . Mouth lining pink. Subadult specimen QM J88147 View Materials similar to others but slightly darker ( Figure 3D View FIGURE 3 ), possibly approaching slough, and with sutures between infralabials and supralabials dark brown .

Colour and pattern in preservative: As with the holotype, colours and patterns are as in life but slightly faded and all traces of lemon and yellow colouration are lost.

Variation. One genotyped but unvouchered individual (SMZ1327 [ MT720720 View Materials ]; Figure 3E View FIGURE 3 ) paler than all other individuals with a faint peach-coloured, fully regenerated tail, and a zigzag border to the pale vertebral stripe. Another photographed but unsampled subadult individual ( Figure 3F View FIGURE 3 ) has a tail pattern consisting of four irregular blotches with the appearance of paired ocelli.

Etymology. The specific epithet iris is in reference to the goddess Iris in Greek mythology. Iris was the goddess of the rainbow and was beautiful. The association with this gecko is that it too is beautiful. The name is used as a noun in apposition. Informally, the name is also a reference to the beautiful iris of this species.

The common name of Gilbert Ground Gecko is chosen because of its location in the Gilbert Range, its proximity to the Gilbert River, and in reference to Gilberton Station, where it occurs.

Comparison with other species. Comparisons are presented in the order of: sympatric and geographically close congeners first, then all other congeners in alphabetical order, and finally a visually similar species ( Diplodactylus vittatus ) that occurs in the region. Descriptions and measurements of species other than L. iris sp. nov. are from the species descriptions referenced and Storr et al. (1990).

From the sympatric Lucasium steindachneri ( Figure 6B View FIGURE 6 ), L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. steindachneri : c. 43 mm SVL; Boulenger 1885), nares in narrow contact with rostral scale ( L. steindachneri : nares not contacting rostral), and colour and pattern ( Lucasium steindachneri : usually a pink to reddish or orange-brown base colour, with the pale vertebral region often broken up into box-like patterns, which have given it the common name box-patterned gecko).

From Lucasium immaculatum ( Figure 6C View FIGURE 6 ), L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by generally larger size ( L. immaculatum : up to 54 mm; see discussion in Doughty 2015), nares in contact with rostral scale ( L. immaculatum : nares not contacting rostral), and pattern ( L. immaculatum : dorsal stripe narrower, usually with numerous lateral branches that sometimes break into pale spots and flecks). The two species are geographically separated by c. 150 km (this paper).

From Lucasium stenodactylus (Boulenger, 1896) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by nares in narrow contact with rostral scale ( L. stenodactylus : rarely in contact), and colour ( L. stenodactylus : background colour red-brown to orange-brown; this paper). The two species are geographically separated by c. 300 km.

From Lucasium alboguttatum (Werner, 1910) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. alboguttatum : up to 57 mm SVL; Storr et al. 1990), usually relatively shorter tail ( L. alboguttatum: TL /SVL 0.78–1.06; Storr et al. 1990), and pattern ( L. alboguttatum : an irregular pale mid-dorsal zone of blotches, bordered by large yellowish spots). The two species are geographically separated by c. 3,000 km.

From Lucasium bungabinna , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by generally larger size ( L. bungabinna : up to 56 mm SVL; Doughty & Hutchinson 2008), and colour ( L. bungabinna : cream and red-brown to orange-brown). The two species are geographically separated by c. 1,700 km.

From Lucasium byrnei ( Lucas and Frost, 1896) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. byrnei : up to 56.5 mm SVL; Kluge 1967), pattern ( L. byrnei : usually four irregular pale patches on the dorsal surface, often marked with dark spots occupying single scales), and dorsal and lateral scales homogeneous ( L. byrnei : scales heterogeneous, numerous small conical tubercles present; Lucas & Frost 1896). The two species are geographically separated by c. 500 km.

From Lucasium damaeum ( Lucas & Frost, 1896) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. damaeum : up to 55 mm SVL; Kluge 1967), larger apical lamellae ( L. damaeum : not enlarged), and pattern ( L. damaeum : usually large lateral pale spots). The two species are geographically separated by c. 550 km.

From Lucasium maini ( Kluge, 1962) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. maini : up to 49 mm SVL; Kluge 1967), larger apical lamellae ( L. maini : not, or only slightly, enlarged; Kluge 1962, 1967), and pattern ( L. maini : an irregular pale mid-dorsal zone of blotches, bordered by large white spots that are paler than the mid-dorsal zone). The two species are geographically separated by c. 2,000 km.

From Lucasium occultum , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. occultum : c. 40–41 mm SVL; King et al. 1982; Wilson & Swan 2017), and pattern ( L. occultum : four irregular pale greyish patches on the dorsal surface each roughly rectangular). The two species are geographically separated by c. 1,400 km.

From Lucasium squarrosum ( Kluge, 1962) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by generally larger size ( L. squarrosum : up to 57 mm SVL; Storr et al. 1990), and pattern ( L. squarrosum : a zigzag or irregularly bordered vertebral stripe, bordered below by large pale spots). The two species are geographically separated by c. 2,200 km.

From Lucasium wombeyi (Storr, 1978) , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by larger size ( L. wombeyi : up to 54 mm SVL; Storr et al. 1990), and pattern ( L. wombeyi : irregular, large, pale dorsal and lateral blotches often enclosing smaller yellowish spots). The two species are geographically separated by c. 2,300 km.

Features to distinguish L. iris sp. nov. from Diplodactylus vittatus ( Figure 6D View FIGURE 6 ) are presented here because of their relatively close geographic proximity (c. 50 km; see Discussion). From D. vittatus , L. iris sp. nov. is distinguished by generally larger size ( D. vittatus : up to c. 56 mm SVL; this paper), longer, narrower tail ( D. vittatus: TL / SVL 0.40–0.59; TW/TL 0.26–0.37; this paper), and the presence of precloacal pores in males ( D. vittatus : absent).

Distribution, habitat, and conservation status. Lucasium iris sp. nov. is known from a small area, c. 100 km south of Georgetown ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). The distribution falls on the boundary of the Kidston province of the Einasleigh Uplands bioregion and the Gilberton Plateau province of the Gulf Plains bioregion ( Sattler & Williams 1999). Lucasium iris sp. nov. occurs in low rocky hills with many small escarpments, talus slopes, and washout areas. Individuals have been encountered foraging on the ground at night (n = 7) and sitting at the entrance of a narrow burrow with just the head protruding (n = 3). Foraging at night after emerging from burrows is typical for Lucasium (the authors, pers. obs.; King & Horner 1993; Cogger 2014; Wilson & Swan 2017). This suggests its behaviour and habitat are similar to its congeners. The vegetation at sites where most L. iris sp. nov. were found is dominated by Acacia shirleyi, Eucalyptus and Corymbia spp. woodlands, often with sparse Melaleuca citrolens , generally over Triodia spp. hummocks ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 ). This conforms to Regional Ecosystem 2.10.5, which is:

Acacia shirleyi woodland over bare ground, annuals and Triodia pungens . Occurs on plateau surfaces and margins on Mesozoic sandstones; skeletal soils and rock outcrops.

The remainder were found in habitats mapped as, and conforming to, RE 9.11.28, which is: Woodland to open forest of Acacia shirleyi (lancewood) +/- Eucalyptus microneura (Georgetown box) +/- E. crebra (narrow-leaved ironbark) (sens. lat.). The shrub layer is generally absent to mid-dense, though areas of Melaleuca citrolens (scrub teatree) with emergents of the above canopy taxa may occur. Occurs on undulating hills and rises and on metamorphosed sandstone outcrops. and 9.11.16, which is:

Woodland to open woodland of Eucalyptus crebra (narrow-leaved ironbark) +/- Corymbia erythrophloia (red bloodwood) or C. pocillum +/- Corymbia spp. A sub-canopy layer of canopy species, Terminalia aridicola (arid peach) and/or Erythroxylum ellipticum (kerosene wood) may be present. The shrub layer

varies from isolated plants to mid-dense and can include Denhamia cunninghamii (yellowberry bush), Vachellia bidwillii (corkwood wattle), Petalostigma spp., Erythrophleum chlorostachys (Cooktown ironwood), Bursaria incana (prickly pine) and other Acacia spp. The ground layer is grassy and dominated by Themeda triandra (kangaroo grass) and/or Heteropogon contortus (black speargrass). Occurs on red to brown soils derived from metamorphic geologies on steep to rolling hills.

At all sites, the vegetation was interspersed with bare, rocky ground, areas of accumulated leaf litter, and fallen woody debris.

None of the L. iris sp. nov. records are from a protected area, but the species probably occurs in Rungulla National Park. The species is not known from similar habitat in Blackbraes National Park, 46 km to the south-east ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ), despite extensive fauna (including reptile) surveys there ( Vanderduys et al. 2012a; authors, unubl. data). Areas mapped as the same REs from which Lucasium iris sp. nov. has been recorded occur beyond the immediate vicinity of its known locations in three areas: 1. Rungulla National Park, which is 3 km southwest of known locations ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ); 2. to the east around the Gilbert River and the Gilbert Range; and 3. c. 20 km to the north-west in the Gregory Range, in the vicinity of the Gilbert and Robertson Rivers. Rungulla National Park requires detailed reptile surveys but the other two areas have been extensively surveyed without demonstrating the presence of L. iris sp. nov. (the authors, unpubl. data; Vanderduys et al. 2012a, 2012b; Couper et al. 2016; Bourke et al. 2017; Hoskin et al. 2018).

Area of occupancy (AOO) and extent of occurrence (EOO) may be estimated using “known, inferred or project- ed sites of present occurrences” ( IUCN 2001, 2019). We estimated AOO and EOO for Lucasium iris sp. nov. based on the habitat at known locations and the underlying RE mapping. We did not include similar habitats on sandstone or metamorphic geology from areas 2 and 3 listed above because of the inferred absence of Lucasium iris sp. nov. from them, based on surveys. We restricted our calculations to the eastern part of the Gregory Range and mostly north of the Gilbert River ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). The likely AOO based on this habitat is c. 2,700 km 2, and EOO c. 3,000 km 2. Within the EOO, the actual mapped area of the three REs that records have come from is 1,430 km 2. Although the EOO is less than a threshold in the IUCN category B1 (<20,000 km 2; Vulnerable), and the species would likely also fit subcategory ((a): known from ≤ 10 locations), there is no indication of any additional threatening factors such as severe fragmentation, known or projected decline, or extreme fluctuations in population size or distribution ( IUCN 2019). Regional ecosystem mapping suggests less than 900 ha (<0.3%) is cleared within the EOO. Therefore, current data does not suggest that Lucasium iris sp. nov. fits any IUCN threatened category. An unresolved threat is fire, explored in the Discussion.

Sympatric geckos. Lucasium iris sp. nov. is known to co-occur with two other predominantly ground-dwelling diplodactylid geckos: L. steindachneri and Diplodactylus platyurus Parker, 1926 . Differentiation of L. iris sp. nov. from L. steindachneri is dealt with above. In addition, though we did not measure sympatric L. steindachneri in the field, L. iris sp. nov. generally appears larger and slightly more robust than L. steindachneri (the authors, pers. obs.). Lucasium iris sp. nov. is not likely to be confused with D. platyurus because of the latter’s short, fat tail (TL/SVL 28–43%, TW/TL 44–79%; Oliver et al. 2014a) and undifferentiated supralabial scales ( Oliver et al. 2014a), and typical D. platyurus dorsal pattern in this area of a broad pale zone bordered by a dark messy zigzag pattern ( Figure 6E View FIGURE 6 ). The only other primarily ground-dwelling gecko known to co-occur is the gekkonid Heteronotia binoei (Gray, 1845) , which is readily distinguished by the presence of tubercles across the dorsum and the absence of a vertebral stripe ( Figure 6F View FIGURE 6 ). Two other regionally sympatric species of similar build that could potentially be confused with L. iris sp. nov. are Lucasium immaculatum and Diplodactylus vittatus . Lucasium immaculatum is known from Littleton National Park, c. 150 km to the NW of the area occupied by L. iris sp. nov., but still on the Einasleigh Uplands ( Figure 1C View FIGURE 1 ). The closest D. vittatus records come from Blackbraes National Park, 46 km SE from L. iris sp. nov. Characters presented in the section ‘Comparison with other species’ differentiate these two species from L. iris sp. nov.

In addition to the species above, the following geckos are known to occur with, or in close proximity to, L. iris sp. nov.: Carphodactylidae : Nephrurus asper Günther, 1876 ; Diplodactylidae : Amalosia rhombifer (Gray, 1845) , Oedura castelnaui (Thominot, 1889) , O. argentea Hoskin, Zozaya & Vanderduys, 2018 , Strophurus taeniatus (Lönnberg & Andersson, 1913) ; Gekkonidae : Gehyra dubia (Macleay, 1887) , G. einasleighensis Bourke, Pratt, Vanderduys & Moritz, 2017 .

| QM |

Queensland Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.