Cliona amplicavata Rützler, 1974

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4370.5.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:88C1C5A7-3C4E-416D-A716-D8B3D62E720D |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BC2D87B2-7B6F-E557-5FB5-87E6FAC5FC5E |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi (2018-01-15 06:15:27, last updated 2019-09-26 01:55:04) |

|

scientific name |

Cliona amplicavata Rützler, 1974 |

| status |

|

Cliona amplicavata Rützler, 1974

Material examined. MZUCR.368: Bahía Salinas, 15 m, 3.III.2011, coll. and det. Cristian Pacheco Solano . CIMAR.CU.12: Bahía Culebra, 3 m, 28.VI.2011, coll. and det. Cristian Pacheco Solano . MZUCR.369: Playa Mantas , 3 m, 11.IV.2011, coll. and det. Cristian Pacheco Solano . MZUCR 370 , MZUCR 372 : Playa Mantas , intertidal, 16.IX.2011, coll. and det. Cristian Pacheco Solano . CIMAR.LF.01: Reserva La Flor , 3 m, 14.II.2012, coll. and det. Cristian Pacheco Solano .

External morphology. Alpha morphology, discrete, circular papillae, no tendency for merging observed, 0.5–1 mm in diameter. Live color ochre.

Excavation. Multicamerare erosion with oval chambers, separated by walls commonly about 200 µm thick ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 ). Largest observed chamber 4.6 x 3.6 mm. Sponge-generated erosion scars forming continuous pitting on chamber walls, pits sharp-edged and 36–90 mm in diameter ( Fig. 2B View FIGURE 2 ).

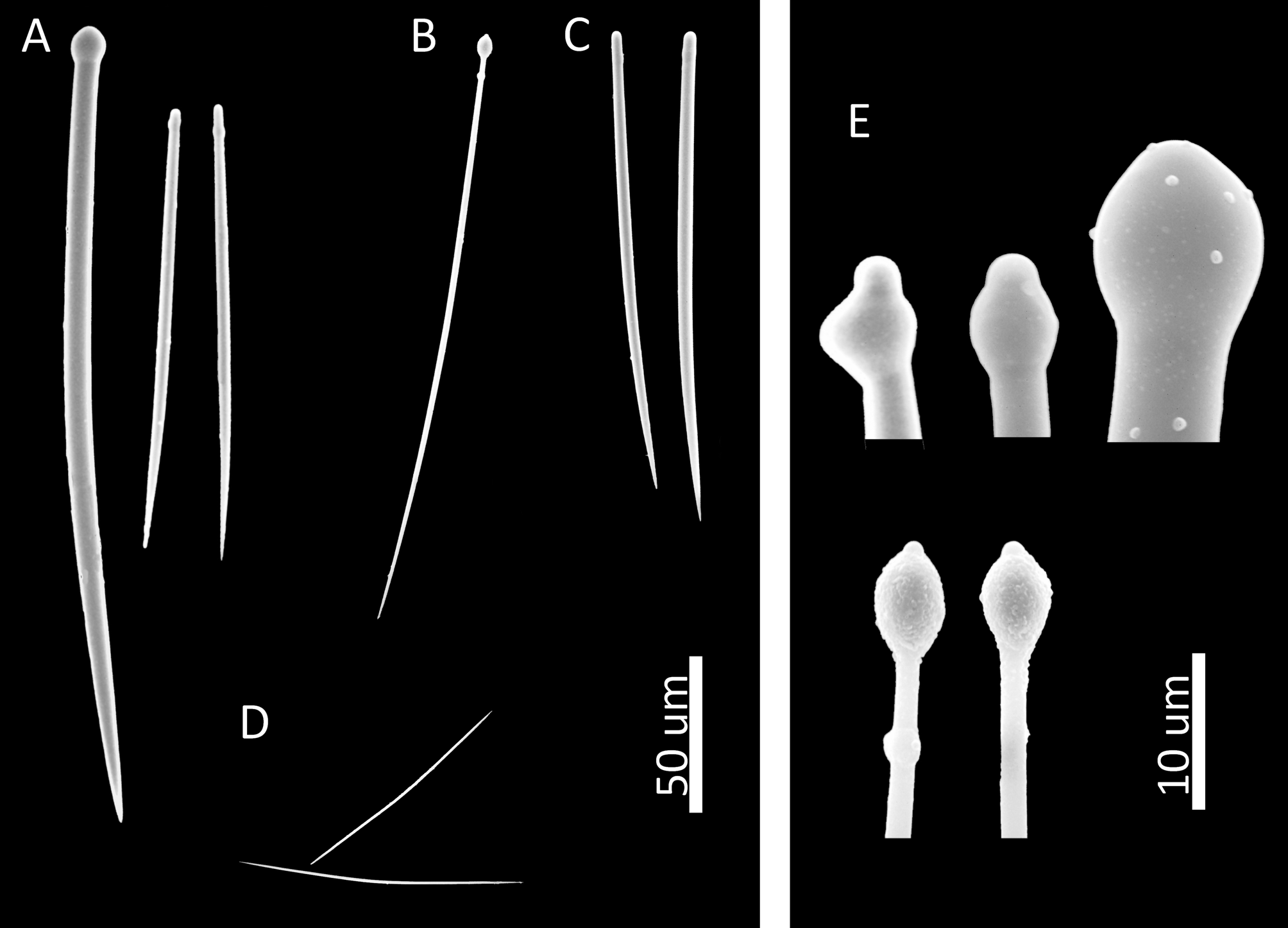

Spicules. Megascleres tylostyles in two size classes, with the larger roughly twice as long as the shorter. Larger type slightly curved at mid-shaft, with well-formed tyles, often slightly subterminal. Smaller type slightly curved in lower third, with strongly displaced, subtle tyles, or styles. Microscleres thin, hastate raphides, slightly curved midshaft. Spicule dimensions: tylostyles 115–282 µm (x=¯229.6, σ=37.4) x 1 –7.5 µm (x=¯5.2, σ=1.9); styles 80–156 µm (x̅=121, σ=17.0) x 2.5–4.5 µm (x̅=3.7, σ=0.8), raphides 65–140 µm (x̅=89.6, σ=18.2) ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ).

Ecology. Found in massive and branching corals: in live Pavona gigantea Verrill, 1869 , and in fragments of dead Porites lobata Dana, 1846 and Pocillopora sp., between 3 and 15 m depth.

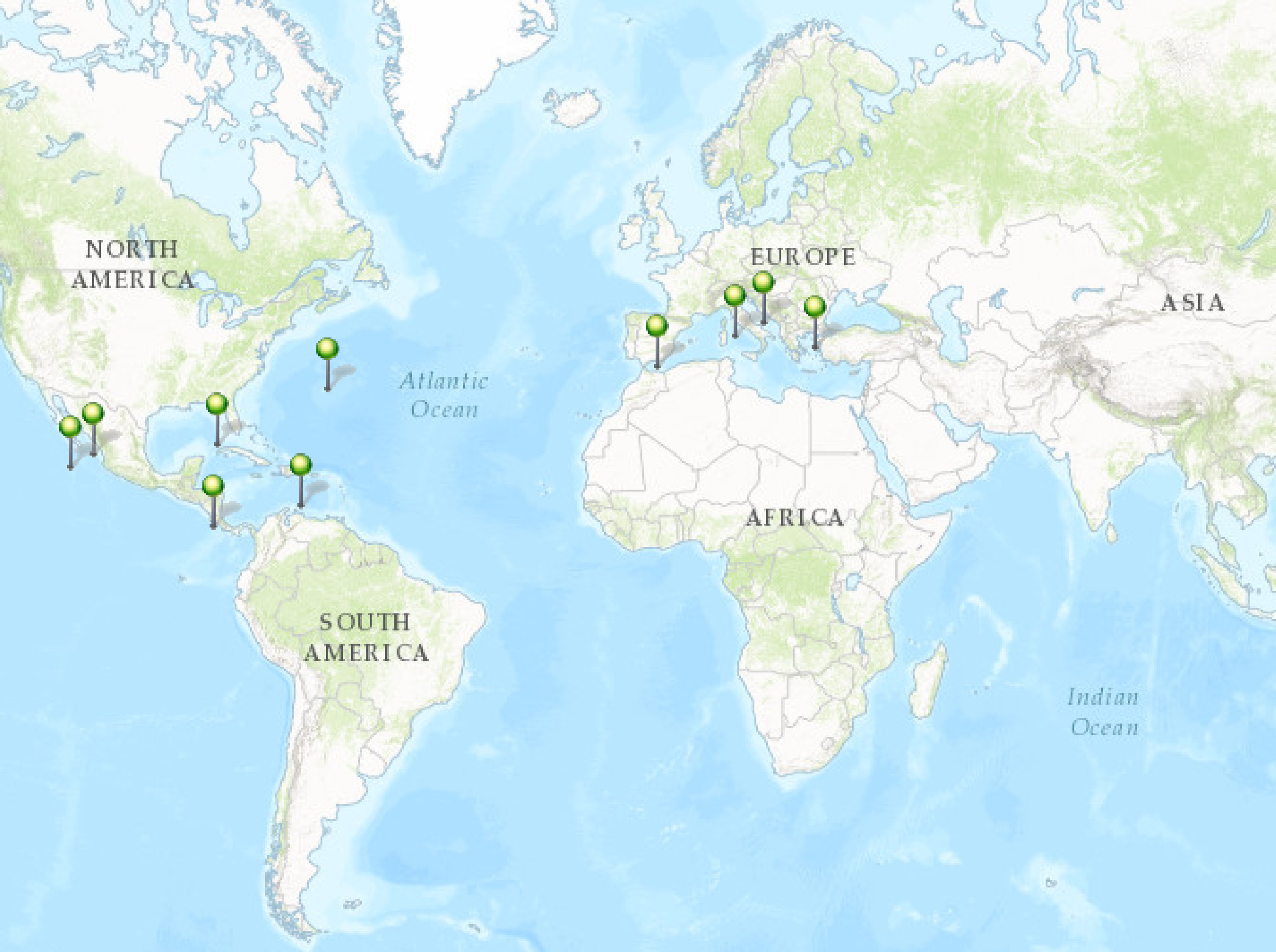

Distribution and previous records. The species was described by Rützler (1974) from Bermuda, growing in dead Diploria sp. and Montastrea sp., and is also known from the Caribbean ( Rützler et al. 2014) and the Gulf of Mexico ( Ugalde et al. 2015). Accounts from the Mediterranean ( Rosell & Uriz 2002) are considered as inaccurate ( Soest et al. 2016). Carballo et al. (2004) first reported C. amplicavata in the ETP, found along the Mexican coast, excavating Pocillopora sp. and mollusk shells ( Carballo et al. 2008a, 2008b). This distribution range is presently extended for the Pacific to Central America: Nicaragua and Costa Rica ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ).

Remarks. Only few Cliona species have a spicule complement combining tylostyles and raphides, including C. amplicavata , Cliona dissimilis Ridley & Dendy, 1886 , Cliona raphida Boury-Esnault, 1973 , and maybe erroneously Cliona cf. celata Grant, 1826 (e.g. Schönberg 2000; discussed in Rosell & Uriz 2002). It is presently not known whether raphides in some Cliona species represent immature stages of tylostyles or are raphides in the true sense (e.g. Custódio et al. 2002). Therefore, the taxonomic value of raphides remains uncertain for some clionaids. However, the regular and size-uniform appearance of the thin oxeate spicules in our samples suggested that here they signified a separate spicule type.

We presently exclude C. cf. celata sensu Schönberg (2000) from further considerations. While this species also occurs in the Pacific and has very similar spicule dimensions, as well as erosion traces with several chambers, it does not have tylostyles in two size classes. C. dissimilis is also an Indo-Pacific species with similar, if possibly slightly larger tylostyles than in our material, but it has consistently been described as being dark orange or bright red and in beta growth ( Ridley & Dendy 1886; Fromont et al. 2005). Fromont et al. (2005) did not report tylostyles in two size classes. The Atlantic C. raphida was described as brown and appears to have larger tylostyles and shorter raphides than in our West Pacific specimens ( Boury-Esnault 1973). Again, C. raphida is not known for two sizes of megascleres. Tylostyle dimensions from our material best resemble those of C. amplicavata from Bermuda and the Gulf of Mexico ( Rützler 1974; Ugalde et al. 2015), and Mexican Pacific sponges conspecific with our samples were previously identified as C. amplicavata ( Carballo et al. 2004, 2008a; Vega 2012). However, after closer inspection it became clear that the specimens from Bermuda had tylostyles with a slightly larger size range ( Rützler et al. 2014). In addition, C. amplicavata erosion traces were described to consist of predominantly single, large erosion chambers, not well matching our observations. However, while this was not noted in the original description, C. amplicavata appears to have two size classes of tylostyles (see Fig. 22 View FIGURE22 in Rützler 1 974). The Mediterranean Cliona adriatica Calcinai et al., 2011 has tylostyles and styles like in our material, with the smaller styles forming the external skeleton, the palisade ( Calcinai et al. 2011). We have not confirmed the distribution of the different spicule types in our samples, but the spicule dimensions of C. adriatica appear too large to match our material, and it was not reported to have raphides. Its excavation chambers are also smaller than those in our samples.

At this stage C. amplicavata is the best taxonomic match with our material. Some characters in our samples were not quite as originally described, with the Pacific material being ochre, the Atlantic material yellow, and the Pacific papillae and erosion chambers comparatively small and raphides short. However, discrepancies were not very strong, and they can be explained with morphologic plasticity that can be caused by different environmental conditions ( Rosell & Uriz 1991; Bavestrello et al. 1993; Hill 1999). The occurrence of two size classes of megascleres in Atlantic ( Fig. 22 View FIGURE22 in Rützler 1974) and Pacific specimens ( Carballo et al. 2004; Ugalde et al. 2015) compelled us to follow the earlier examples and to identify our sponges as C. amplicavata .

The present decision would suggest that C. amplicavata crossed the isthmus, which may have occurred by opening the Panama Canal. This is however not a common occurrence ( Laubenfels 1936), and a previous molecular study on excavating sponges in this area identified separate cryptic species rather than conspecifity of sponge populations on the Atlantic and Pacific sides of Central America (e.g. Boury-Esnault et al. 1999). Future studies should include molecular analyses to confirm or reject this possibility (see Nichols & Barnes 2005).

Carballo, J. L., Cruz-Barraza, J. A. & Gomez, P. (2004) Taxonomy and description of clionaid sponges (Hadromerida, Clionaidae) from the Pacific Ocean of Mexico. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 141, 353 - 397. https: // doi. org / 10.1111 / j. 1096 - 3642.2004.00126. x

Fromont, J., Craig, R., Rawlinson, L. & Alder, J. (2005) Excavating sponges that are destructive to farmed pearl oysters in Western and Northern Australia. Aquaculture Research, 36, 150 - 1 62. https: // doi. org / 10.1111 / j. 1365 - 2109.2004.01198. x

Bavestrello, G., Bonito, M. & Sara, M. (1993) Influence of depth on the size of sponge spicules. Scientia Marina, 57, 415 - 4 20.

Boury-Esnault, N. (1973) Resultats scientifiques des Campagnes de la ' Calypso' X. Campagne de la ' Calypso' au large des cotes atlantiques de l'Amerique du Sud (1961 - 1962). I. 29. Spongiaires. Annales de l'Institut Oceanographique, 49, 263 - 295.

Boury-Esnault, N., Klautau, M., Bezac, C., Wulff, J. & Sole-Cava, A. M. (1999) Comparative study of putative conspecific sponge populations from both sides of the Isthmus of Panama. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 79, 39 - 50. https: // doi. org / 10.1017 / s 0025315498000046

Calcinai, B., Bavestrello, G., Cuttone, G. & Cerrano, C. (2011) Excavating sponges from the Adriatic Sea: description of Cliona adriatica sp. nov. (Demospongiae: Clionaidae) and estimation of its boring activity. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 91, 339 - 346. https: // doi. org / 10.1017 / s 0025315410001050

Carballo, J. L., Cruz-Barraza, J. A., Nava, H. & Bautista, E. (2008 a) Esponjas perforadoras de sustratos calcareos: importancia en los ecosistemas arrecifales del Pacifico este. CONABIO, Mexico City, 187 pp.

Carballo, J. L., Bautista-Guerrero, E. & Leyte-Morales, G. E. (2008 b) Boring sponges and the modeling of coral reefs in the east Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Serie s, 356, 113 - 1 22. https: // doi. org / 10.3354 / meps 07276

Custodio, M. R., Hajdu, E. & Muricy, G. (2002) In vivo study of microsclere formation in sponges of the genus Mycale (Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida). Zoomorphology, 121, 203 - 2 11. https: // doi. org / 10.1007 / s 00435 - 002 - 0057 - 9

Hill, M. S. (1999) Morphological and genetic examination of phenotypic variability in the tropical sponge Anthosigmella varians. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 44, 234 - 247.

Laubenfels, M. W. de (1936) A comparison of the shallow-water sponges near the Pacific end of the Panama Canal with those at the Caribbean end. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 83, 441 - 466. https: // doi. org / 10.5479 / si. 00963801.83 - 2993.441

Nichols, S. A. & Barnes, P. A. (2005) A molecular phylogeny and historical biogeography of the marine sponge genus Placospongia (Phylum Porifera) indicate low dispersal capabilities and widespread crypsis. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 323, 1 - 5. https: // doi. org / 10.1016 / j. jembe. 2005.02.012

Ridley, S. O. & Dendy A. (1886) Preliminary report on the Monaxonida collcted by H. M. S. ' Challenger'. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 107, 325 - 351, 470 - 493. https: // doi. org / 10.1080 / 00222938609459982

Rosell, D. & Uriz, M. J. (1991) Cliona viridis (Schmidt, 1862) and Cliona nigricans (Schmidt, 1862) (Porifera, Hadromerida): evidence which shows they are the same species. Ophelia, 33, 45 - 53. https: // doi. org / 10.1080 / 00785326.1991.10429741

Rosell, D. & Uriz, M. J. (2002) Excavating and endolithic sponge species (Porifera from the Mediterranean: species descriptions and identification key. Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 2, 55 - 86. https: // doi. org / 10.1078 / 1439 - 6092 - 00033

Rutzler, K. (1974) The burrowing sponges of Bermuda. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, 165, 1 - 32. https: // doi. org / 10.5479 / si. 00810282.165

Rutzler, K., Piantoni, C., Soest, R. W. M. van & Diaz, M. C. (2014) Diversity of sponges (Porifera) from cryptic habitats on the Belize Barrier Reef near Carrie Bow Cay. Zootaxa, 3805 (1), 1 - 129. https: // doi. org / 10.11646 / zootaxa. 3805.1.1

Schonberg, C. H. L. (2000) Bioeroding sponges common to the Central Australian Great Barrier Reef: descriptions of three new species, two new records, and additions to two previously described species. Senckenbergiana Maritima, 30, 161 - 221. https: // doi. org / 10.1007 / bf 03042965

Soest, R. W. M. van, Boury-Esnault, N., Hooper, J. N. A., Rutzler, K., Voogd, N. J. de, Alvarez de Glasby, B., Hajdu, E., Pisera, A. B., Manconi, R., Schonberg, C. H. L., Klautau, M., Picton, B., Kelly, M., Vacelet, J., Dohrmann, M., Diaz, M. C., Cardenas, P. & Carballo, J. L. (2016) World Porifera Database. Available from: http: // www. marinespecies. org / porifera (accessed 10 December 2016)

Ugalde, D., Gomez, P. & Simoes, N. (2015) Marine sponges (Porifera: Demospongiae) from the Gulf of Mexico, new records and redescription of Erylus trisphaerus (Laubenfels, 1953). Zootaxa, 3911 (2), 151 - 183. https: // doi. org / 10.11646 / zootaxa. 3911.2.1

Vega, C. (2012) Composicion y afinidades biogeograficas de esponjas (Demospongiae) asociadas a comunidades coralinas del Pacifico Mexicano. Doctoral thesis, Instituto Politecnico Nacional, Mexico, 231 pp.

FIGURE 2. Cliona amplicavata bioerosion. A) Chamber of excavation (arrow) and B) sponge scars in form of wall pitting of the erosion chambers.

FIGURE 3. Spicules of Cliona amplicavata: A) tylostyles and derivates in two size classes, B) immature tylostyle, C) styles, D) raphides, E) enlarged heads of tylostyles.

| CIMAR |

Universidad Catolica de Valparaiso, Centro de Investigaciones del Mar |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |