Physeter macrocephalus, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6607611 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6607619 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B70F87E5-4664-8733-428C-F91FF6ECFD82 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Physeter macrocephalus |

| status |

|

Sperm Whale

Physeter macrocephalus View in CoL

French: Grand Cachalot / German: Pottwal / Spanish: Cachalote

Other common names: Cachalot, Pot Whale, Spermacet Whale

Taxonomy. Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“in Oceano Europao.”

This species is monotypic.

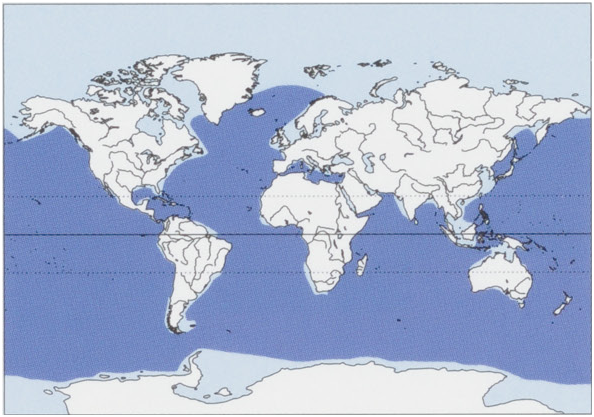

Distribution. Almost cosmopolitan, found from the edges of polar pack ice to the equator in both the Southern and Northern hemispheres. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 1520- 1920 cm (males) and 1040-1250 cm (females); up to more than 70,000 kg (males) and to 24,000 kg (females).

Typical values are 1500 cm and 45,000 kg for males and 1100 cm and 15,000 kg for females. Sperm Whales are the most sexually dimorphic of all cetaceans in body length and weight. They are primarily dark gray, but skin can appear dark brown when viewed in bright sunlight. Their enormous head constitutes about 25-33%of animal’s total body length. A single blowhole is located asymmetrically on the left side at the front end of the rostrum. Twentyto 26 pairs ofconical teeth erupt only on the narrow, under-slung lower jaw. Small eyes are set far back on the head. Smooth skin occurs on head and flippers and appears dimpled past the eyes. Sperm Whales have flat, paddle-shaped flippers andlarge, triangular-shapedflukes with relatively straight trailing edges.

Habitat. Deep, ice-free ocean waters across the globe, and in deep semi-enclosed seas (e.g. Mediterranean) but not enclosed seas (e.g. Black and Red). Female Sperm Whales and their dependent young generally inhabit tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters deeper than 1000 m and with sea surface temperatures greater than c.15°C. Subadult and adult males range more widely; the range oflarge adult males includes ice-free deep waters near both poles that may beclose to 0°C.

Food and Feeding. Sperm Whales feed primarily on cephalopods. They are generalists, their prey being manyofthe larger, deep-ocean mesoand bathypelagic species. Preyincludes over 25 species of cephalopods, ranging from chiroteuthids weighing less than 100 g to giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) weighing over 400 kg, as well as over 60 species of bottom-dwelling fish ofvarious sizes. Males feed on larger species and larger individuals in the same taxa as females, and also on species foundat higher latitudes. Males are also more likely than females to prey onfish, sharks, and rays. In a single foraging dive, a female Sperm Whale will seize around 37 squid, consuming approximately 750 per day. Male Sperm Whales, their prey being larger, consume an estimated 350 squid per day. In general, foraging dives reach depths of 300-1200 m, andlast 30-45 minutes, but occasionally depths of 1000-2000 m may be achieved during dives of more than 60 minutes.

Breeding. Prolonged breeding of Sperm Whales lasts from late winter through early summer. Sperm Whales in the Northern Hemisphere typically breed from January to August, with activity intensifying between March and June. In the Southern Hemisphere, breeding extends from July to March, peaking between September and December. The mating season of whales residing in tropical waters near the equator is unknown. Males reach sexual maturity by their late teens but do not participate in breeding activities until at least their late twenties when they reach social maturity. Female Sperm Whales are sexually mature by nine years and give birth to single young every 4-6 years; reproductive rates decline significantly with age. Gestation lasts for 14-16 months. Neonates weigh ¢.1000 kg and are ¢.400 cm long at birth. Weaning begins at two years, although individuals may continue suckling for manyyears. Maximumlongevity recorded is 77 years.

Activity patterns. Sperm Whales spend ¢.75% oftheir lives foraging. Most foraging dives last 30-45 minutes and are 300-1200 m in depth, followed by 7-10 minutes at the surface. Young whales take shorter, shallower dives than adults. Female Sperm Whales staggerforaging dives, leaving some adults at surface to protect young. After foraging bouts, Sperm Whale social groups may gather at or nearthe surface for hours at a time. Sometimes individuals lay still and quiet, closely clustered or “logging,” apparently resting. At other times, they may be much more active, socializing with a great deal ofaerial behavior, emitting vocalizations called “codas” and creaks, and rolling about and touching one another. Large male Sperm Whales may also “log” quietly at the surface for long periods or socialize if they are with groups of females.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Female Sperm Whales are highly social and nomadic. They travel in long-termsocial units consisting of c.11 individuals, including adult females with and without offspring. They rely on allomaternal care, where females collectively care for offspring in the social group, even those that are not their own. In the Pacific Ocean, two or more social units from the same vocal clan mayjoin to form temporary groups. Vocal clans may be comprised of thousands of females with distinctive and culturally transmitted vocalizations, and can be sympatric. In the North Atlantic, social units rarely group with other units and vocal clans are geographically distinct. Female home ranges in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean are estimated to span ¢.1500 km. At the surface, groups move c.4-7 km/h. Less 1s known about male sociality. Pubertal males leave their natal units at 4-21 years old and gather in loosely grouped bachelor groups. As they mature, males travel with fewer individuals. The largest males are frequently solitary and may be found from the tropics to near the polar ice edges.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List, with the Mediterranean subpopulation classified as Endangered. The Sperm Whale is on Appendices I and II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The International Whaling Commission (IWC) catch limits are set to zero, although Japan continues to issue controversial permits for up to ten Sperm Whales annuallyforscientific purposes anda few individuals are taken eachyear for subsistence onthe island of Lembata in Indonesia. Wide-ranging offshore dispersal of Sperm Whales makes accurate abundance estimates difficult, but worldwide abundance currentlyis estimated at 300,000-450,000 individuals. The international moratorium on commercial whaling curtailed the most direct threat to Sperm Whale survival but a number of conservation concerns exist today, including vessel collisions; anthropogenic noise due to shipping, naval sonar and oil and gas explorations; bioaccumulation of chemical pollutants; entanglement in marine debris and fishing gear; loss of prey due to overfishing or climate-induced ecosystem changes; disturbance from whale watching; and the potential of illegal or renewed whaling efforts at unsustainable levels.

Bibliography. Aoki et al. (2012), Barnes (1996), Beale (1839), Berzin (1972), Best, PB. (1967 1968, 1969a, 1969b, 1970, 1983), Best, PB. et al. (1984), Caldwell & Caldwell (1966), Christal et al. (1998), Clarke, M.R. (1980), Clarke, R. (1953, 2006), Clarke, R. et al. (1968, 1988, 1994), Cranford (1999), Davis et al. (1997), Dolin (2007), Ellis (2011), Evans (2008), Feldhamer et al. (2007), Frank (2009), Gero, Engelhaupt, Rendell & Whitehead (2009), Gero, Engelhaupt & Whitehead (2008), Gosho et al. (1984), Husson & Holthuis (1974), Ivashchenko et al. (2011), Kasuya (1999a), Kawakami (1980), Kemp (2012), Linneaus (1758), Lund et al. (2010), Madsen (2012), Mchedlidze (2009), Melville (1851), Mesnick, Evans et al. (2003), Mesnick, Taylor et al. (2011), Mitchell (1983), Mizroch & Rice (2013), Mustika (2006), NMFS (2010b), Norris & Harvey (1972), Pitman et al. (2001), Reeves (2002), Rendell & Whitehead (2005), Rendell et al. (2012), Rice (1989, 1998, 2009a), Schulz et al. (2008, 2011), Smith, Lund et al. (2010), Smith, Reeves et al. (2012), Starbuck (1878), Taylor et al. (2008g), Tennessen & Johnsen (1982), Wade et al. (2012), Weilgart & Whitehead (1997), Whitehead (1996, 2002, 2003, 2006, 2012), Whitehead, Antunes et al. (2012), Whitehead, Coakes et al. (2008), Whitehead, Dillon et al. (1998), Whitehead, Waters & Lyrholm (1991).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.