Magnolia buenaventurensis Á.J.Pérez & E.Rea, 2023

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.592.2.5 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7843262 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B043E26F-6672-FFAD-B9A1-FB8FF815F866 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Magnolia buenaventurensis Á.J.Pérez & E.Rea |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Magnolia buenaventurensis Á.J.Pérez & E.Rea , sp. nov. ( Figs 1–3 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 )

Type:— ECUADOR. El Oro: Cantón Santa Rosa, Parroquia Torata , Reserva Buenaventura , Fundación Jocotoco , sector SambotamboBirón , 1300–1400 m, 6 May 2022, Pérez et al. 11777 ( holotype: QCA! (fl, fr, fl in alcohol); isotypes G! (fl bud), GUAY! (fl), LOJA! (fl), MOL! (fl bud), QCNE! (fl bud), UTPL! (fl bud)) .

Magnolia buenaventurensis resembles M. mashpi and M. mindoensis , but can be differentiated from the former by having a stipular scar on the petiole (vs. none), glabrous leaves (vs. pubescent beneath), petals 8 (vs. 6) and ellipsoid fruits (vs. globose); from the latter by having a longer stipular scar on the petiole, glabrous leaves (vs. pubescent), petals 8 (vs. 6), fewer stamens (50–53 vs. 84–86) and more carpels (12–15 vs. 9–10).

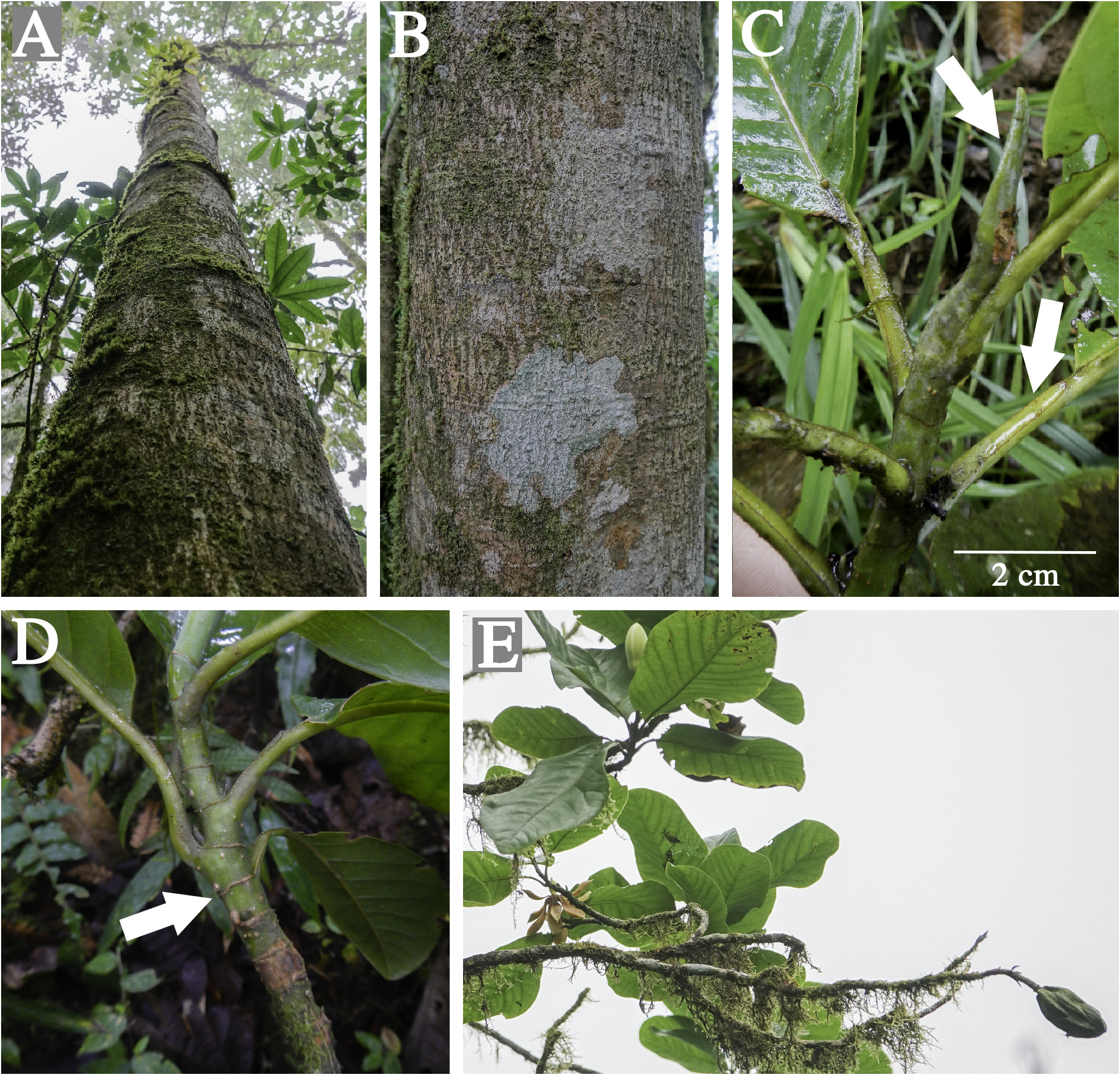

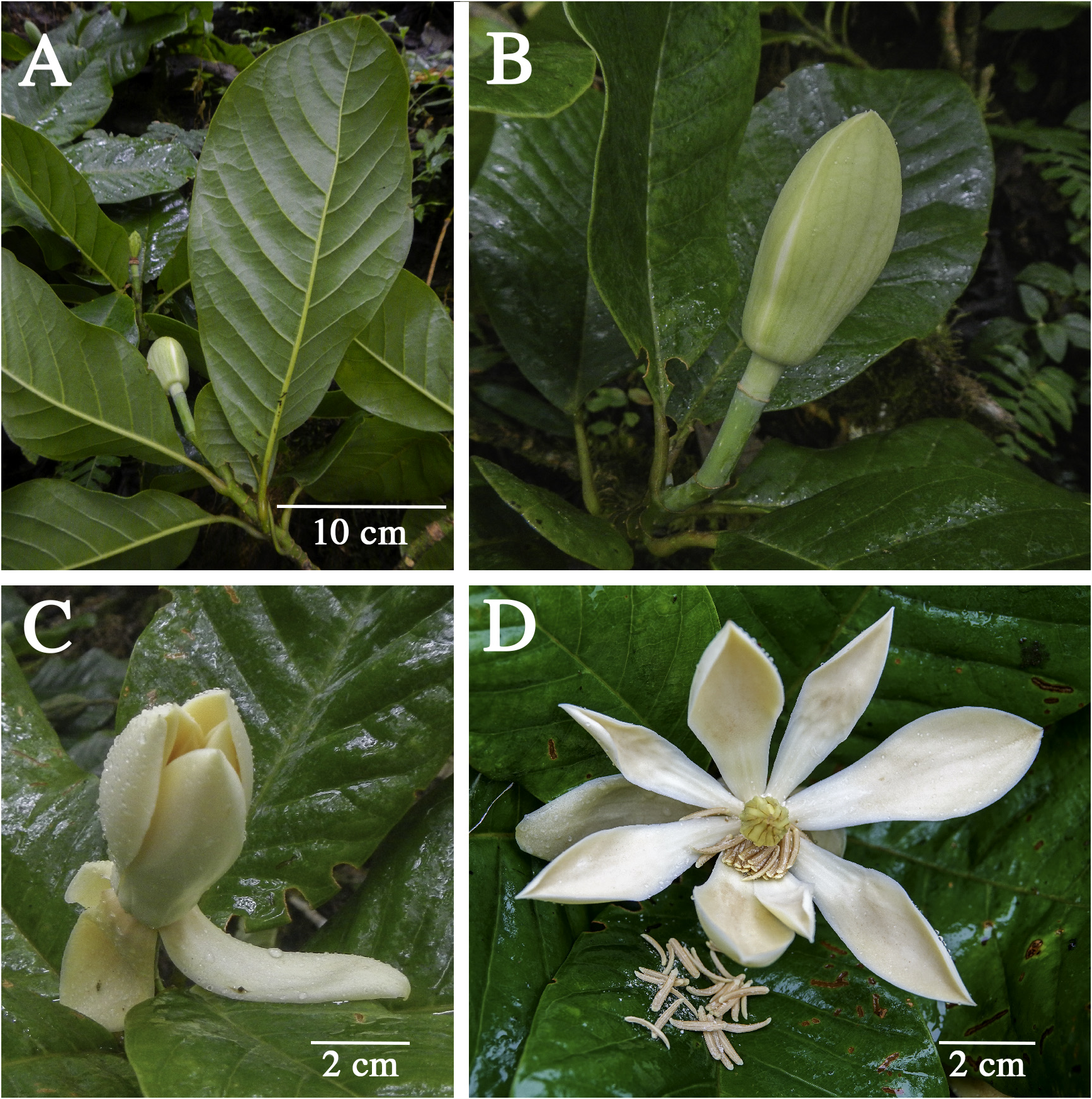

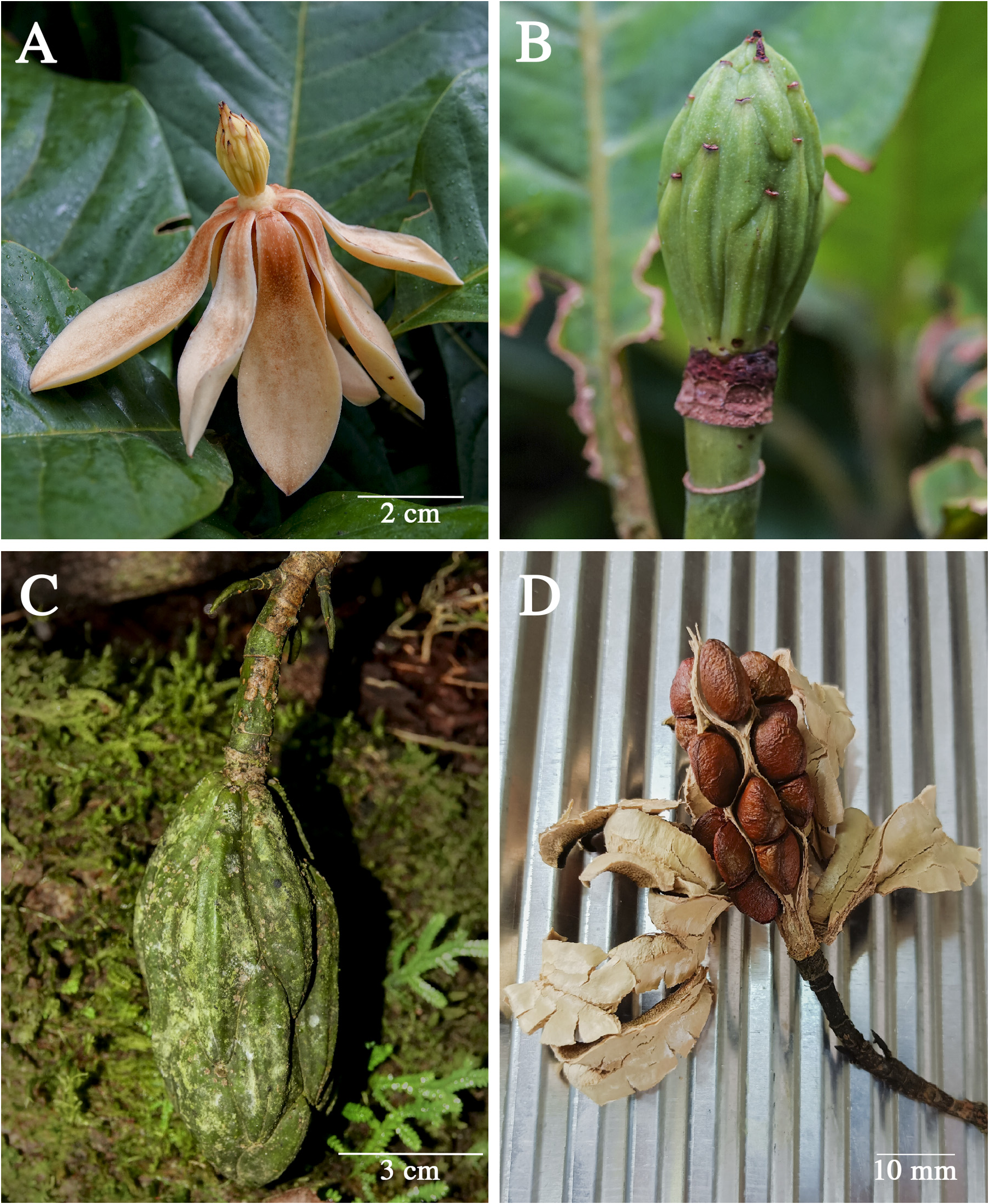

Trees 10–30 m tall; 15–60 cm dbh. Outer bark smooth, fragrant and creamy white. Young parts, such as branches, petioles and leaf blades glabrous. Twig internodes 0.5–1.2(–1.5) × 0.6–0.8(–1) cm, glabrous, with oblong lenticels. Stipular scar nearly reaching the apex of the petiole. Petiole subterete, 1.30–4.10(–5.00) × 0.15–0.20(–0.30) cm. Leaves obovate-elliptic, 10.0–25.5(–30.0) × 6.2–13.8(–14.5) cm, green above, pale green below, glabrous on both sides, apex acute to rounded, base cuneate, margin entire, secondary veins 10–15 on each side of the midrib, midrib canaliculate above, raised beneath; reticulate tertiary venation. Flowers solitary, 8–10 cm in diam; bract 1, 3.2–5.0 × 3.1–4.5 cm, broadly ellipsoid, glabrous, glaucous-green; flower buds ellipsoid; peduncle 0.5–1.4 cm long, lower internodes 0.5– 1.2(–2.0) cm long, glabrous; sepals 3, creamy white, navicular, obovoid, 4.2–5.5 × 2.1–2.5 cm, glabrous, base truncate, apex obtuse to rounded; petals 8, creamy white, cochleate, navicular, oblanceolate, fragrant, the three outer ones 5.4–6.0 × 1.8–2.1 cm, concave in the upper third, the five inner ones 4.5–5.5 × 1.0– 1.5 cm, gradually narrower basally; stamens 50–53, 1.0–1.4 × 0.1–0.2 cm; gynoecium ellipsoid, 1.9–2.1 × 1.0– 1.1 cm, stigma 0.9 cm long, deciduous, yellowish white, glabrous, carpels 12–15. Fruit ellipsoid, 7.0–8.5 × 4.3 cm, with circumscissile dehiscence, glabrous, green; seeds 1–2 per carpel, sub-prismatic, fragrant, angled, 9–12 × 8–11 mm, shiny, with a red sarcotesta.

Etymology:— Referring to the type locality, a 3546-ha reserve owned and managed by the Jocotoco Foundation, which is devoted to preserving the last remnants of tropical and cloud forest from 400–1600 m on the south-western hills of the Andean Cordillera.

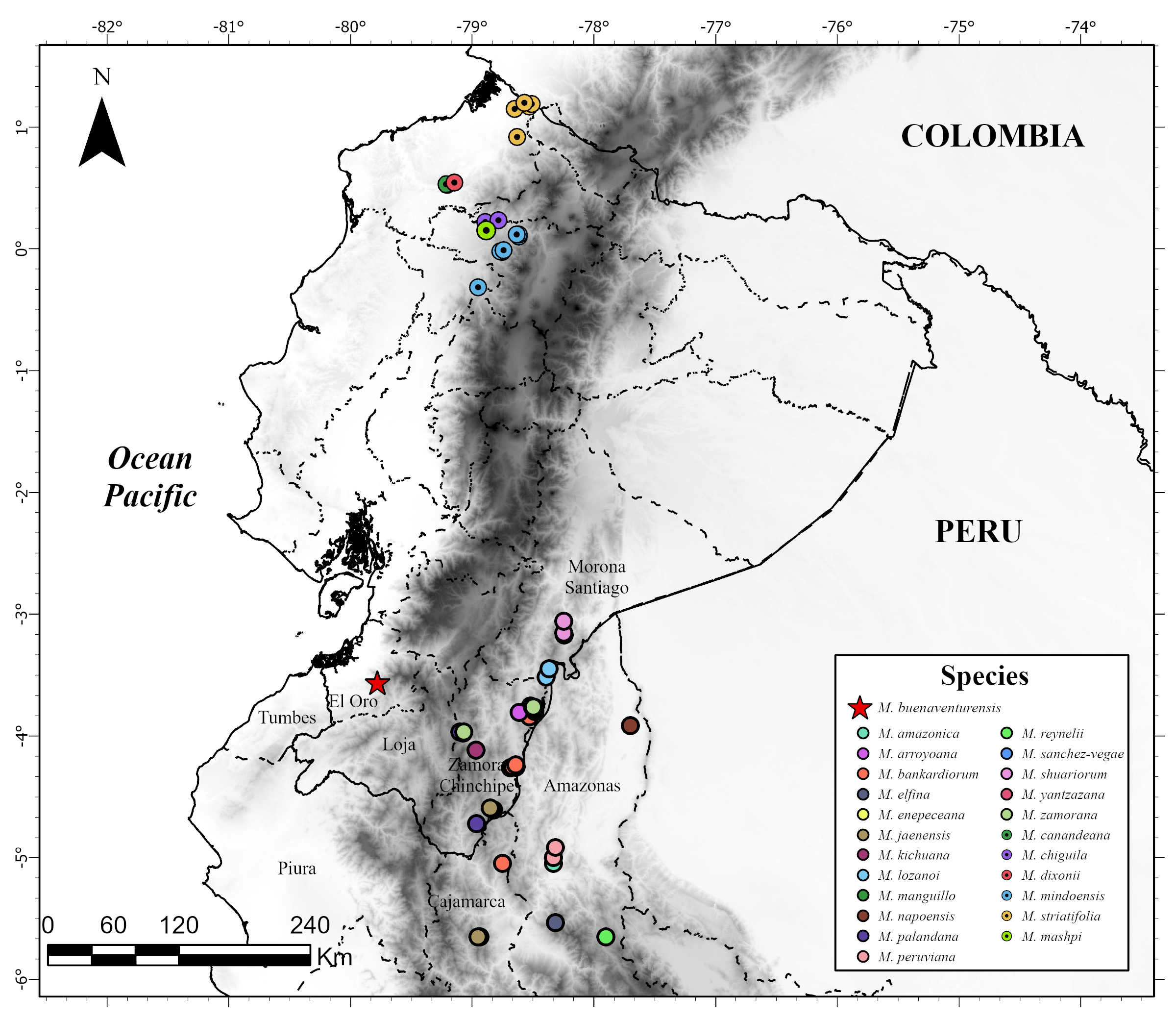

Distribution, habitat and ecology:— Known thus far only from the type locality, the montane forest remnants at the Sambotambo-Birón, between 1300–1600 m, in El Oro Province ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ). According to the Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador 2013, this area lies in the Catamayo-Alamor evergreen piedmont forest (BsPn02) that harbours high diversity and endemism ( Cerón et al. 1999; Myers et al. 2000) as a result of the Andes and Tumbesian región influence. Field observations indicate that M. buenaventurensis co-occurs with the following tree species: Guatteria microcarpa (Annonaceae) , Dictyocaryum lamarckianum and Wettinia kalbreyeri (Arecaceae) , Guarea kunthiana (Meliaceae) and Roupala montana (Proteaceae) . The endangered mantled howler monkey ( Alouatta palliata ) also inhabits these forest patches ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

Phenology:— Flowering and fruiting throughout the year.

Conservation status:— Known only from one population of eight adult individuals in less than 5 km 2. Given the narrow distribution of the species and the constant threats (e.g., pasture expansion for cattle, selected logging and mining activities), the species should be considered critically endangered (CR B2ab(iii)) ( IUCN 2022). In situ and ex situ propagation programs are urgently needed.

Additional specimens examined:— ECUADOR. El Oro: Cantón Santa Rosa, Parroquia Torata, Reserva Buenaventura , Fundación Jocotoco , sector Sambotambo-Birón , 1300–1400 m, 22 Dec 2021, Pérez et al. 11744 ( GUAY, LOJA, QCA, UTPL); ibid., 7 May 2022 (fl), Pérez et al. 11789 ( G, GUAY, LOJA, QCA fl in alcohol, UTPL) .

Notes:— Magnolia buenaventurensis is the first species in this genus to be found in the south-western flanks of coastal Ecuador, an area of high diversity and endemism ( Cerón et al. 1999; Myers et al. 2000). It belongs to M. sect. Talauma , characterised by the stipules adnate to the petiole and carpels with circumscissile dehiscence ( Figlar & Nooteboom 2004; Wang et al. 2020). Although M. buenaventurensis resembles M. mashpi and M. mindoensis , it can be differentiated from them by vegetative features; all structures are entirely glabrous, the leaf apex is usually rounded, and the stipular scar nearly reaching the apex of the petiole (vs. lacking stipular scar in M. mashpi and shorter stipular scar in M. mindoensis ). Differences in reproductive features are 8 petals (vs. 6 in M. mashpi and M. mindoensis ), 50–53 stamens (vs. 131–132 in M. mashpi and 84–86 in M. mindoensis ), 12–15 carpels (vs. 32 in M. mashpi and 9–10 in M. mindoensis ) and ellipsoid fruit (vs. globose in M. mashpi ).

We have observed a high percentage of fruit abortion at immature stages, which may be caused by inbreeding in this small, isolated population. This phenomenon may result from insufficient insect pollination, and the study of their floral visitors and pollination biology is highly recommended ( Kevan & Viana 2003, Potts et al. 2010). Further exploration is also highly advisable, especially in the Peruvian coastal slopes, to further assess distribution and demographic status ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ). At the same time, seed predation and dispersal studies are also needed to understand the apparent lack of recruitment of juveniles. Both in situ and ex situ conservation actions are urgently required for this species. Propagation by seeds is a priority, but in vitro propagation is also suggested to prevent extinction. The Jocotoco Foundation is monitoring seed production to start a propagation program.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |