Eulemur flavifrons (Gray, 1867)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6638668 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6646246 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/A70287F4-C257-FFA9-FA2D-F5B27F2DF4EB |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Eulemur flavifrons |

| status |

|

Blue-eyed Black

Lemur

Eulemur flavifrons View in CoL

French: Lémur aux yeux turquoise / German: Blauaugenmaki / Spanish: Lémur negro de ojos azules

Other common names: Sclater’s Black Lemur, Sclater’s Lemur

Taxonomy. Prosimia flavifrons Gray, 1867 ,

Madagascar.

The taxonomic status of this lemur has been debated since it was first described in the late 1800s. Due to the lack of locality data for the few museum specimens collected, nothing was known ofits status in the wild untilits “rediscovery” in 1983. Subsequent genetic analysis indicated that it was distinct. It was at first considered to be a subspecies of E. macaco but was made a full species by R. Mittermeier and coworkers in 2008. A zone of hybridization or intergradation with E. macaco has been identified east of the Andranomalaza River in the Manongarivo Mountains and in the foothills of the southern Sambirano, including parts of the Manongarivo Special Reserve. Such individuals are said to resemble E. flavifrons in fur coloration and lack of ear tufts, but they have light brown eyes. Monotypic.

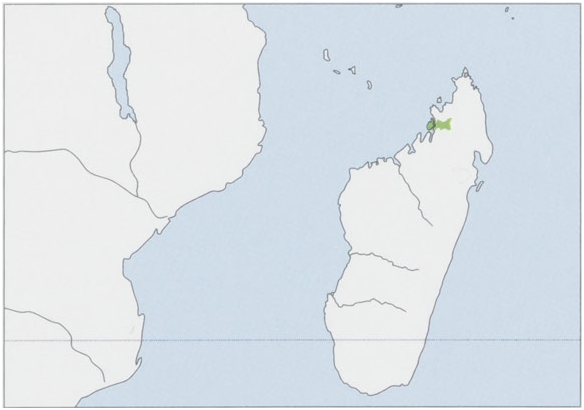

Distribution. NW Madagascar, confined to a few small, isolated areas of forest to the S of the range of the Black Lemur (£. macaco ), from the Andranomalaza River (although it also is reported to the NE ofthe river, E of the Manongarivo Special Reserve) S to the Maevarano River, and E to the Sandrakota River. View Figure

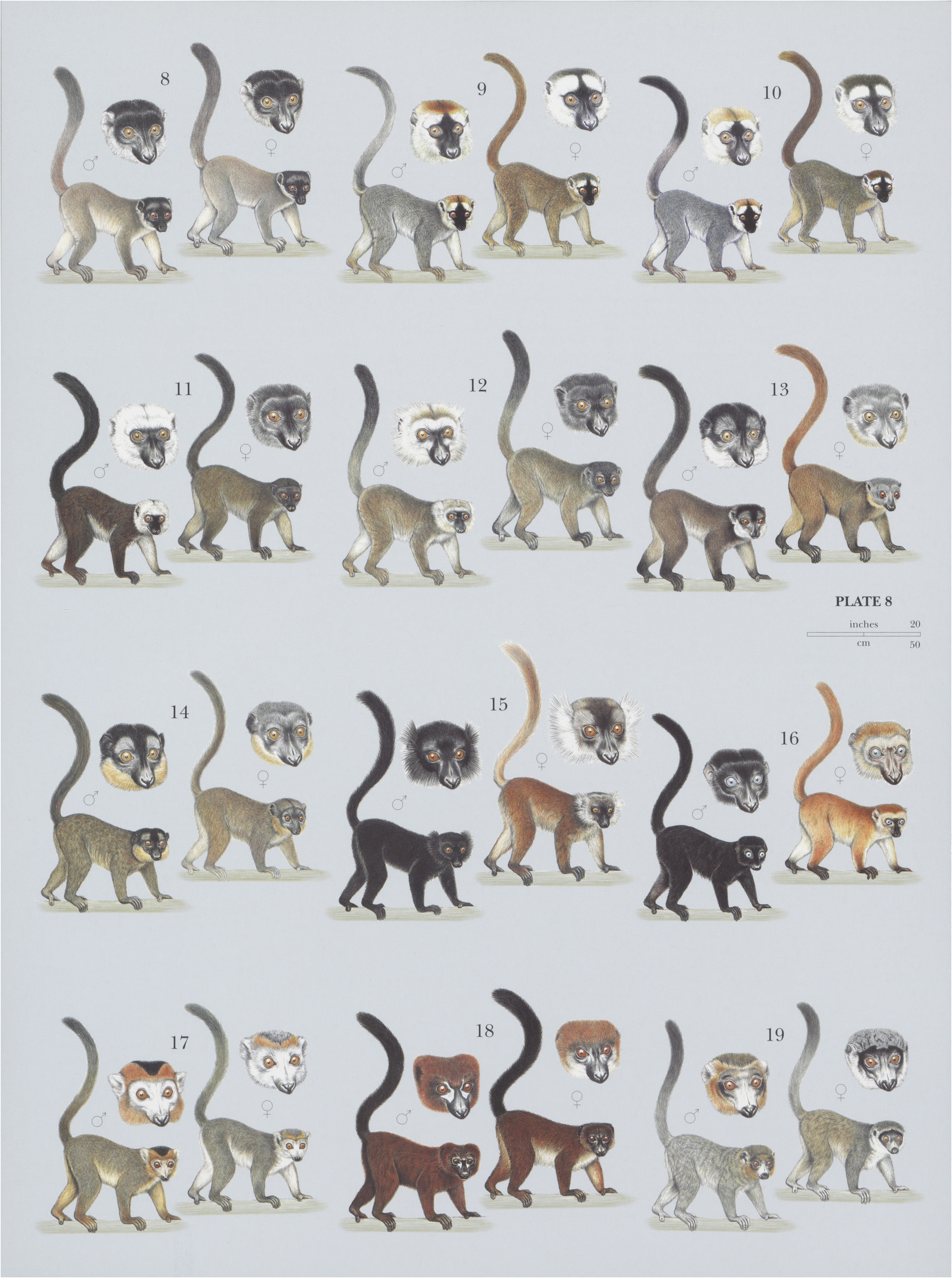

Descriptive notes. Head—body 39-45 cm, tail 51-65 cm; weight 1.8-1.9 kg. The Blueeyed Black Lemur is a medium-sized species. It differs from the Black Lemur , with which it was long considered conspecific, in its slightly smallersize; unique bright blue, gray or green eyes; and lack of ear tufts. It is sexually dichromatic. Males are entirely black (sometimes tinged with brown) and have a distinct ridge of fur on the forehead forming a notable crest. Females are golden-orange to reddish-tan above, with a creamy-white to gray ventral side and darker reddish-brown hands and feet. The muzzle is slate-gray, the face is light, and the crown is rufous-tan.

Habitat. More or less disturbed primary and secondary subtropical subhumid forests, in a transition zone between the Sambirano region to the north and the western dry deciduous forests to the south.

Food and Feeding. During a twelve-month study, Blue-eyed Black Lemurs ate parts of 72 different plant species in 35 families; 52:3% of these were fruits, and 47-7% were leaves. Flowers, insects, insect excretions, and fungi were also consumed. Large quantities of cicadas are eaten at certain times of the year.

Breeding. Mating of the Blue-eyed Black Lemur takes place from late April to early June. A single infant, grayish-black in color,is born between late August and late October, after gestation of c.120-125 days. Twin births do occur but are rare. The first three weeks of the infants life are spent on the mother’s abdomen. From week four, infants can climb onto their mother’s back. After six weeks, infants leave the mother for short bouts of quadrupedal walking along branches. Social and solitary play starts from week seven. Infants are groomed by their mother and other group members. In week ten, infants start ingesting solid food such as leaves, fruits, and flower buds. Infants are fully weaned at 6-7 months of age.

Activity patterns. The Blue-eyed Black Lemur is arboreal and cathemeral. It has a bimodal activity pattern, with peaks during the morning and evening twilight. It has activity bouts during the day and night throughout the year. Nocturnal illumination and the proportion of illuminated lunar disk are positively associated with the amount of nocturnal activity. Total daily activity and nocturnal activity are higher in secondary forest than primary forest.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group size is 2-15 individuals (median range of 7-10). Usually one or two adult females plus one or two subadult females constitute the core of a group; males are more peripheral and frequently change groups. Males also frequently diverge from and re-associate with female core groups during the day. Home range size (4-20 ha) and the way that Blue-eyed Black Lemurs use their home range differ between primary and secondary forest fragments, indicating that they are somewhat able to adapt to different types of habitat. Larger home ranges and lower densities in secondary forest compared with primary forest suggest that the formeris less suitable habitat. Home ranges are smaller in the dry season, and those of neighboring groups overlap.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Blue-eyed Black Lemur is considered one of the most threatened primates in the world, having been included on the 2008 list of the world’s 25 Most Endangered Primates , drawn up every two years by the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group, the International Primatological Society, and Conservation International. Principal threats include forest destruction due to slash-and-burn agriculture and selective logging, continued hunting and trapping (especially by the Tsimihety people in the eastern part of its distribution), and live capture for local pet trade. Up to 570 traps/km? have been found in certain areas. Parts of the very small distribution of the Blue-eyed Black Lemur received official protected area status in 2007 as the Sahamalaza-Iles Radama Parc National, including the Sahamalaza Peninsula and some mainland forests to the north and east. The Sahamalaza Peninsula is also a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. The estimated total world population of the Blue-eyed Black Lemur was under 1000 individuals in 2001.

Bibliography. Albrecht et al. (1990), Andrianjakarivelo (2004), Digby & Stevens (2007), Fausser et al. (2000), Goodman & Schiitz (2000), Koenders, Rumpler et al. (1985), Lernould (2002), Meyers et al. (1989), Mittermeier, Ganzhorn etal. (2008), Mittermeier, Langrand et al. (2010) Petter & Andriatsarafara, (1987), Polowinsky & Schwitzer, C. (2009), Rabarivola et al. (1991), Randriatahina & Rabarivola (2004), Schwitzer & Lork (2004), Schwitzer, C., Moisson et al. (2009), Schwitzer, C., Schwitzer, N. et al. (2006), Schwitzer, N., Kaumanns et al. (2007), Schwitzer, N., Randriatahina et al. (2007), Tattersall (1982), Terranova & Coffman (1997), Volampeno, Masters & Downs (2010, 20114, 2011b).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.