Stegosimpsonia, Tejedor & Goin & Gelfo & López & Bond & Carlini & Scillato-Yané & Woodburne & Chornogubsky & Aragón & Reguero & Czaplewski & Vincon & Martin & Ciancio, 2009

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1206/577.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/A45FA45F-FFCB-E473-FCC9-F9BBE6DFFED7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Stegosimpsonia |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Stegosimpsonia , sp. nov.

Figure 5F View Fig

Also from La Barda and Laguna Fría are several isolated plates of the dorsal carapace of this small dasypodid of similar size to the living Dasypus hybridus or D. septencinctus . The osteoderms are thicker than in other astegotheriins from the same locality, with a more wrinkled surface; lageniform central figure in the movable plates, as in S. chubutana from the Casamayoran (Barrancan subage, Carlini et al. 2002b), but differs from the latter by having fewer and more symmetrically placed foramina on their surface. The central keel of the exposed surface is better defined, with scarce but relatively large foramina on the posterior margin, having a relatively large one at the junction of a proximal sulcus with the external edge of the plate.

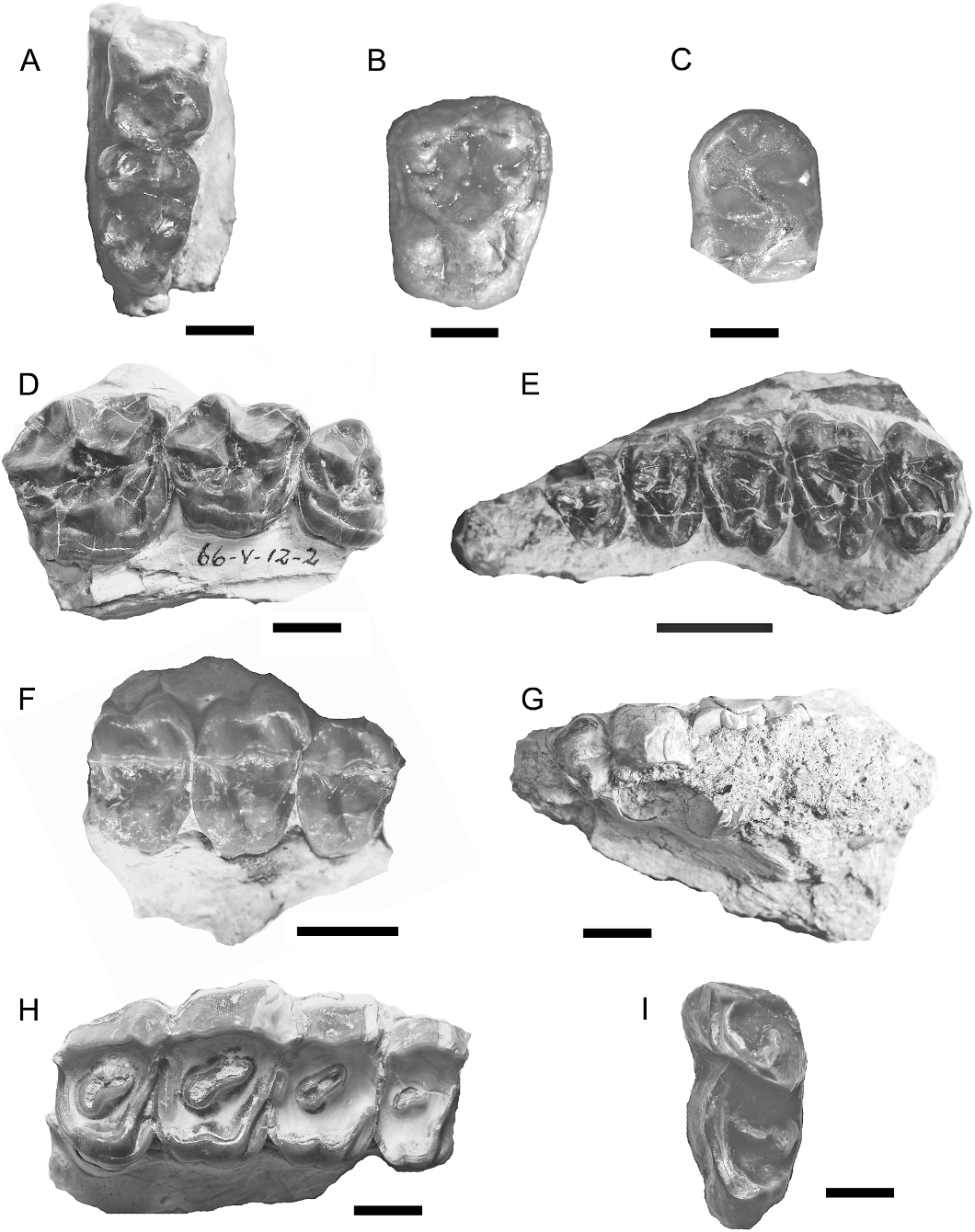

Order Chiroptera Family indet. Gen. et sp. nov. 9 Figure 6 View Fig

Remarkably, two lower bat molars were discovered in Laguna Fría, a well-preserved left m?2 (fig. 6) and a right talonid, both apparently of the same species ( Tejedor et al., 2005). The first appearance of bats in the fossil record is in the early Eocene of North America ( Jepsen, 1966; Novacek, 1985; 1987; Habersetzer and Storch, 1989), Europe ( Russell et al., 1973), and Australia ( Hand et al., 1994). Up to now, the oldest South American record was of middle or late Eocene age at Santa Rosa locality (Yahuarango Formation) in Perú (Czaplewski and Campbell, 2004; Czaplewski, 2005).

The Laguna Fría specimens are identified as bats because of their complete labial cingulum running continuously from the anterior base of the paraconid to the hypoconulid, a probable synapomorphy in the early stages of bat evolution ( Hand et al., 1994). The molar cusps are strongly merged into the molar crests rather than being individualized. The trigonid is anteroposteriorly compressed. The paraconid is small and low, much smaller and slightly less lingually situated than the metaconid. The talonid is not strikingly lower than the trigonid. The entoconid is moderate in height; it bears a straight entocristid (in occlusal view). The cristid obliqua extends from the hypoconid to a point low on the posterior wall of the trigonid slightly labial to the midline of the tooth. The postcristid extends from the hypoconid to a small hypoconulid (the ‘‘nyctalodont’’ condition) and is separated from the entoconid by a small groove. The hypoconulid is fully merged into the postcristid and is not distinguishable as a separate cusp; it merely forms the posteriorly curving lingual terminus of the postcristid and is positioned directly posterior rather than posterolabial to the entoconid. This is a derived condition relative to the primitive tribosphenic arrangement involving distinct talonid cusps (entoconid, hypoconid, and medial or submedial hypoconulid). The primitive tribosphenic condition is present in the archaic bats Ageina , Archaeonycteris , Eppsinycteris , Hassianycteris , Honrovits , Icaronycteris , and Necromantis ( Simmons and Geisler, 1998; Czaplewski, personal obs.). However, the same configuration of the postcristid-hypoconulid as in the Laguna Fría bats is found in other Eocene bats such as Dizzya (Philisidae) , Lapichiropteryx , and Stehlinia (Palaeochiropterygidae) , and certain extinct or extant representatives of the Emballonuridae , Furipteridae , Miniopteridae , Molossidae , Mormoopidae , Natalidae , Phyllostominae, some Rhinolophidae , Rhinopomatidae , and some Vespertilionidae . Although the Laguna Fría bats probably represent a new species, given the few specimens and characters available and their similarity to numerous extinct and extant bats from several lineages, we are unable to assign the Laguna Fría specimens to a taxon more circumscribed than Chiroptera .

South American Native Ungulates Order ‘‘Condylarthra’’ Family Didolodontidae ( Scott, 1913)

The Family Didolodontidae ( Scott, 1913) includes the most primitive South American ungulates, characterized by a low and bunodont dentition. They are recorded at several Patagonian localities in Argentina ( Ameghino, 1906; Simpson, 1948, 1967a) from the Peligran through the Mustersan (Paleocene–?middle Eocene), and from the Itaboraian (late Paleocene) of Saõ José de Itaboraí (Río de Janeiro, Brazil) ( Paula Couto, 1952).

Gen et. sp. nov. 7

Represented by a left mandibular fragment with a well-preserved m3 (LIEB-PV 1611) collected in Laguna Fría. It is about the size of the Protolipternidae , especially Protolipterna ellipsodontoides , from the Itaboraian of Brazil ( Paula Couto, 1952). The m3 shows a strongly arcuate paracristid, as in Didolodontidae and primitive Litopterna ( Bonaparte et al., 1993) , but its more medial and anterior point seems to descend to the trigonid basin. The paraconid is a conspicuous cusp, anterolabially placed with the base connate to the metaconid. Among the Didolodontidae , the paraconid is also a distinct cusp, as in the Peligran Escribania chubutensis ( Gelfo, 1999, 2004) and the Itaboraian taxa Paulacoutoia protocenica and Lamegoia conodonta . In contrast, the paraconid of younger didolodontids shows a trend toward merging to the metaconid, as in the Barrancan subage (late Casamayoran) Didolodus multicuspis or Ernestokokenia , where the paraconid is no longer distinct. The paraconid is variably present in Protolipternidae , but tends to be almost or completely merged to the metaconid. Other distinctive characters are the short mesiodistal extension of the talonid; a small cusp located at the base and anterior to the entoconid; a short, cuspate cristid obliqua that connects the hypoconid with the labial side of the metaconid; and a transverse, sharp cristid running from the entoconid to the posterior side of the hypoconulid. This peculiar cristid divides the talonid basin into an anterior, larger portion that opens posterolingually to the metaconid, and a posterior portion forming the basal contact between entoconid and hypoconulid.

Gen. et. sp. nov. 8 Figure 7A View Fig

This second taxon is represented by a right partial mandible with part of the talonid of m2 and complete m3 (LIEB-PV 1612; fig. 7A) also recovered in Laguna Fría. Even when heavily worn, the m2 hypoconulid seems central and distally placed. This condition is similar to that of Didolodontidae , where the entoconid and hypoconulid are separated, distinct, and never fused as in some Mioclaenidae Kollpaniinae, or close to each other as seen in some Protolipternidae , such as Asmithwoodwardia . This new taxon clearly differs in having the entoconid even larger than the hypoconid, closing the talonid basin. To a lesser degree, Didolodus and Paulacoutoia also show an increase of the entoconid size and reduction of the hypoconulid. The anterior cingulum is short without labial or lingual expansions. The trigonid basin of the m3 is shallow and the base of the protoconid contacts the base of the lingual cusps. The paraconid is very close and slightly labial to the metaconid, and connects the protoconid by a short paracristid more transversely oriented than in the Gen. et. sp. nov. 7. The metaconid is more distal than the protoconid. The talonid basin is almost completely filled by a huge entoconid, even larger than that of m2. There is no distal cingulum. The cristid obliqua is short, low, and rounded, and parallels the toothrow.

Order Litopterna (Ameghino, 1989) Family Protolipternidae (Cifelli, 1983)

This family was recognized by Cifelli (1983a) to contain three small, dentally primitive ungulates, basically from the Itaboraian of Brazil. Two of them, Asmithwoodwardia and Miguelsoria , were previously considered didolodontids. However, based on reassociat- ed postcranial elements ( Cifelli, 1983b), Miguelsoria was reallocated in the Protolipternidae as a primitive member of the Litopterna , together with Protolipterna . Asmithwoodwardia was also included in the Protolipternidae by Cifelli (1983a) without full explanations ( Gelfo and Tejedor, 2004). For the present paper, we use Protolipternidae sensu Mc- Kenna and Bell (1997).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.