Nhanulepisosteus mexicanus, Brito, Alvarado-Ortega & Meunier, 2017

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.26028/cybium/2022-461-002 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10905002 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9D6487A9-F723-7B53-B5FC-FB69FF5CBCAE |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Nhanulepisosteus mexicanus |

| status |

|

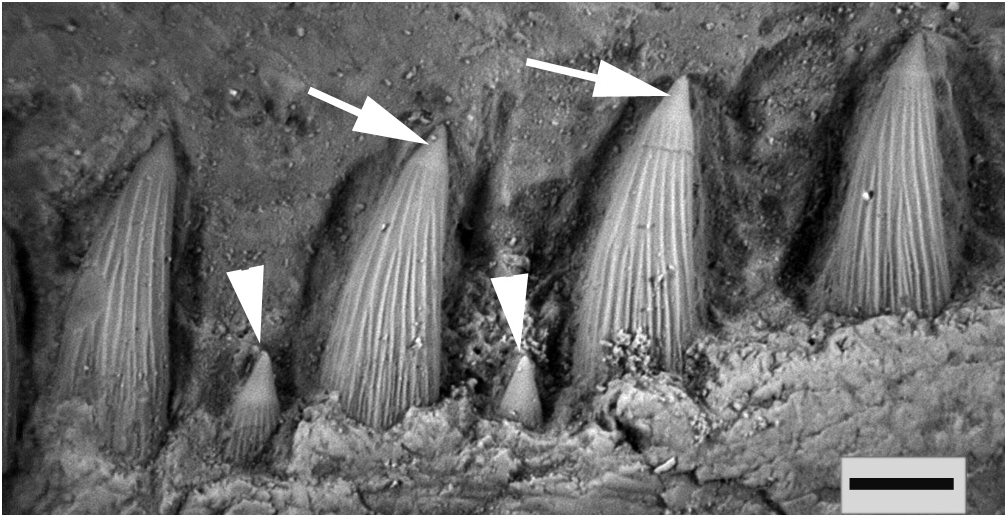

Tooth morphology

The dentary bears two rows of sharply pointed teeth: an outer one presenting numerous relatively small marginal teeth and an inner one with large and robust teeth ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Within the inner row, the most anterior tooth is a hypertrophied fang, being at least five times bigger than the immediately posterior teeth (see Brito et al., 2017: figs 2C, D). The anterior coronoid is a medially curved, anteriorly broad bone that will suture with its antimerous rostrally. It presents small tiny teeth, similar in size to those of the outer row of the dentary.

Contrary to other lepisosteid teeth presenting plicidentine, in where the enamel grooves and striations of the tooth shaft are wider at the base of the tooth (Peyer, 1968; Schultze, 1969; Grande, 2010; Meunier and Brito, 2017), the teeth of † Nhanulepisosteus have very fine external grooves and striations distributed over almost the entire length of the teeth ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). The acrodine cap also seems to be less important.

Tooth histological organization

The sections reveal that there are three types of teeth according to their height, apart from the caniniform fang. They are:

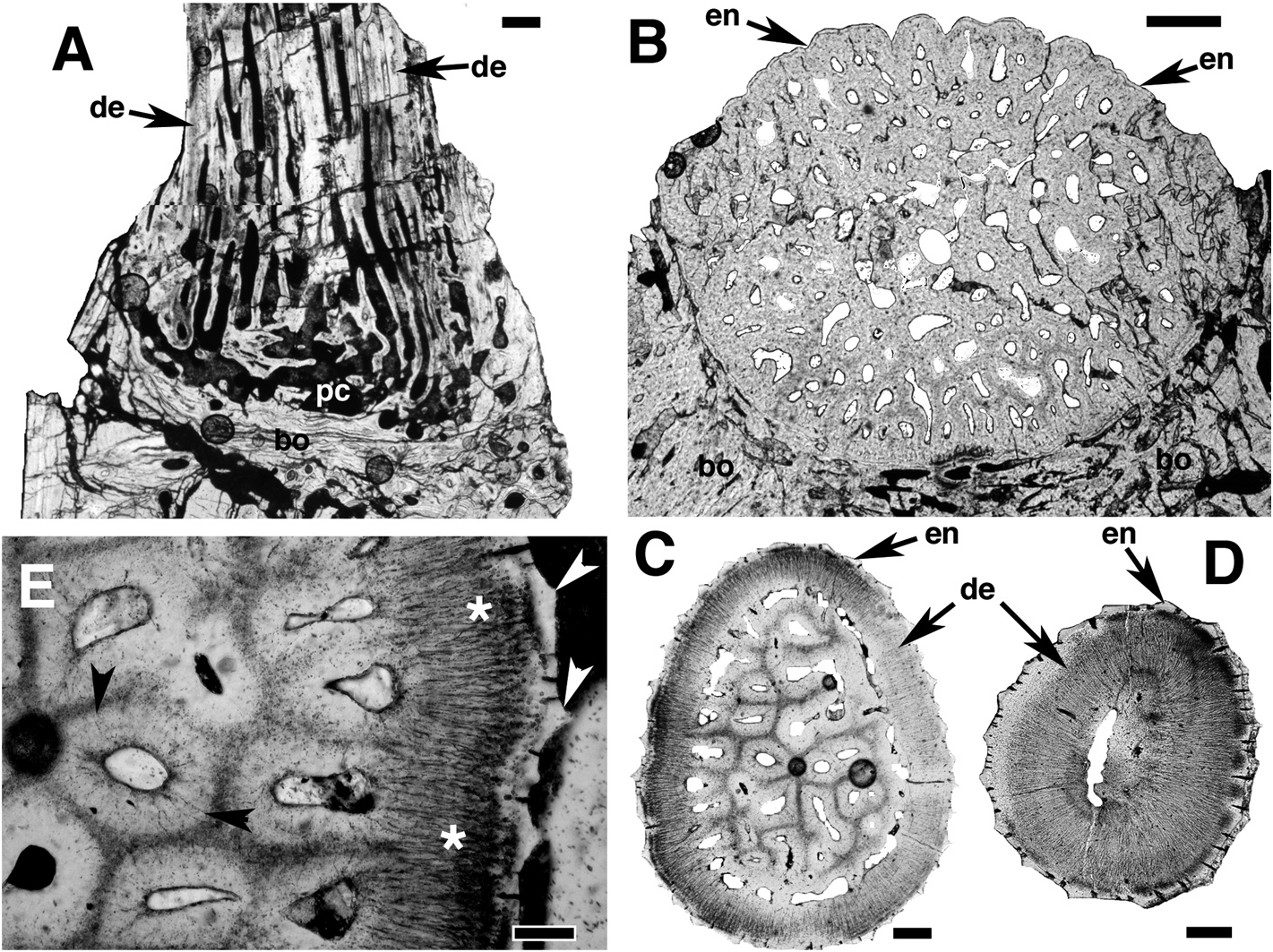

1) The pointed teeth, clearly ridged externally ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 B-E). At their base, the teeth show true pleats of the enamel and dentine layers ( Fig. 3B View Figure 3 ). Yet, upper this basal morphology, pleats are replaced by crests due to more or less thickening of the enamel layer ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 C-E). Under the enamel layer, there is a thick layer of dentine crossed by parallel odontoblastic canalicles ( Fig. 3E View Figure 3 ). In the pulp cavity dentine canals are seen ( Fig. 3B, C View Figure 3 ); they represent a plicidentine organization. This plicidentine occupies the whole pulp cavity ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 A-C), excepted in its upper part ( Fig. 3D View Figure 3 ). The enameloid does not penetrate inside the dentine plies contrary to extant Lepisosteidae ( Schultze, 1969; Meunier and Brito, 2017). The dentine that fills the pulp cavity is constituted of vascular canals surrounded by dentinal tissue that is crossed by orthogonal odontoblastic canalicles ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 C-E); so the present dentine is true osteodentine. We note that † Atractosteus africanus (Late Cretaceous) and † A. occidentalis (Late Cretaceous) also show plies of the pulpar walls of their teeth ( Wiley, 1976: respectively fig. 59 and 38c).

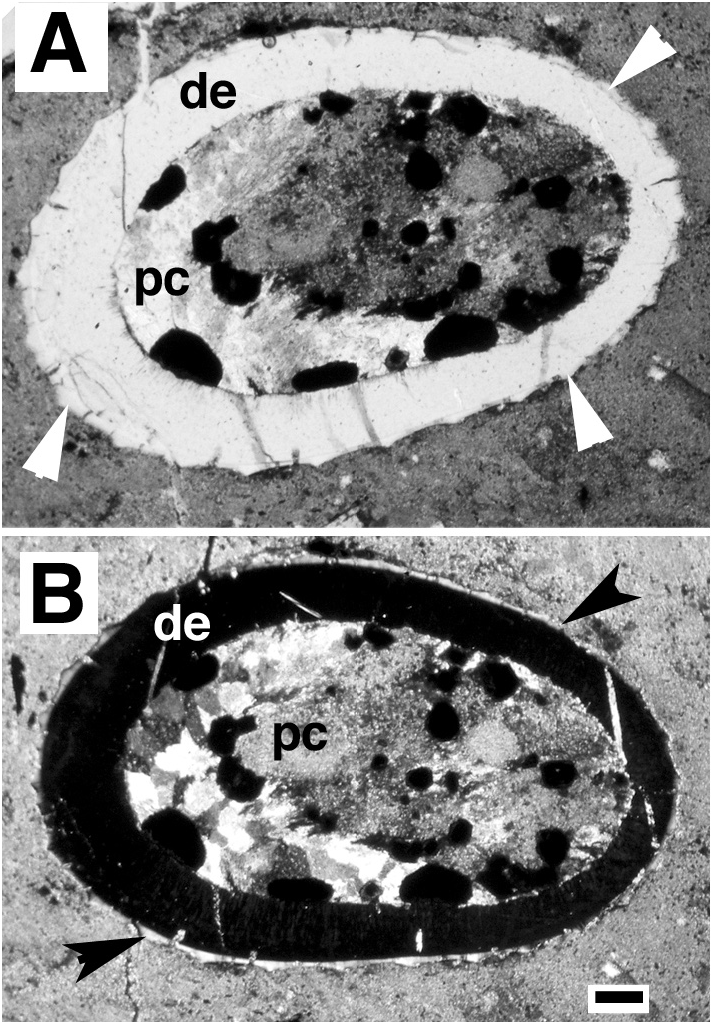

2) Some mid-sized teeth present on the jaws ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). They also have an external ridged enamel layer ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ) that overlays the dentine layer, but the dentine does not show plies in the pulp cavity that is totally empty ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ).

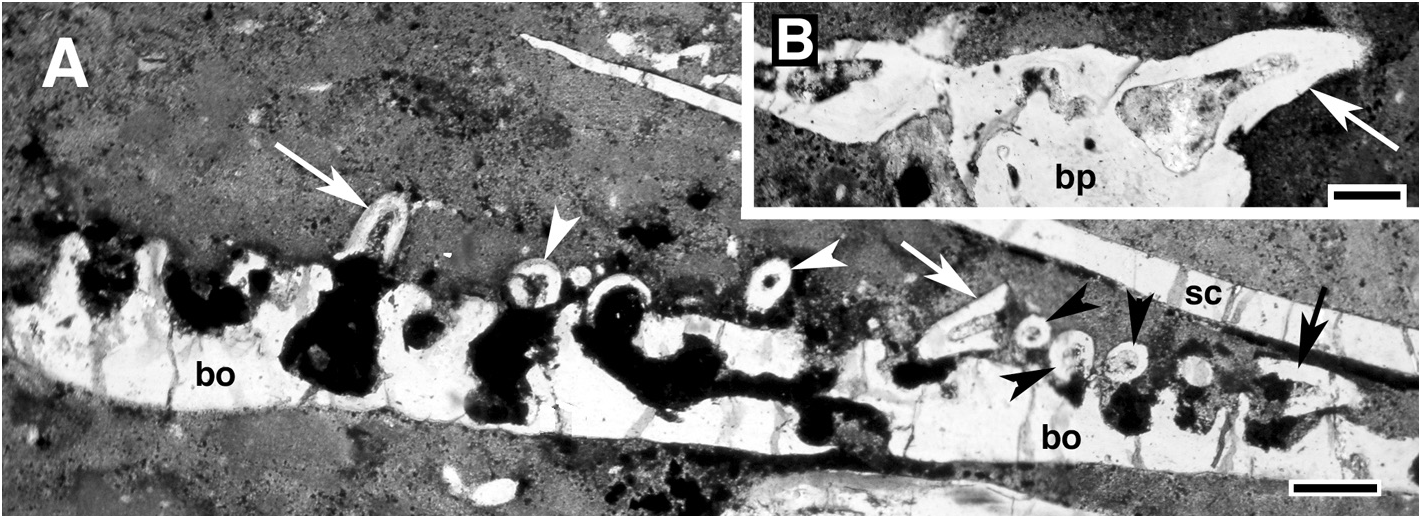

3) The pharyngeal bony plates with numerous small teeth ( Fig. 5A View Figure 5 ), some of them being fixed on the bone ( Fig. 5B View Figure 5 ). These teeth are formed of a dentine cone with a pulp cavity that looks empty, without plies ( Fig. 5A, B View Figure 5 ). Their external surface is not ridged but smooth ( Fig. 5A View Figure 5 ).

Bone histology

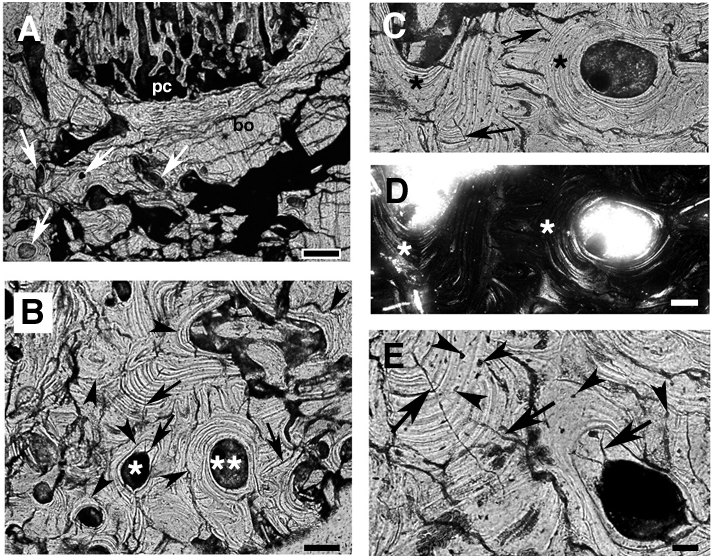

The base of the teeth is fused to the dentary plate by attachment bone ( Figs 3A View Figure 3 , 6A). The supporting bone is essentially constituted of vascular secondary bone with little areas of primary bone ( Figs 3A, B View Figure 3 , 6B-E). The breach aspect of bony tissue is due to the presence of numerous secondary bone osteones ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 B-D) that characterize remodelling processes. This remodelling is directly linked with a regular and frequent replacement of teeth, and probably linked to the large size of teeth (see Brito et al., 2017: fig. 2C, D) that produces large scars when they fall. These impressive teeth can be considered as fangs, and so indicate a predatory diet for † Nhanulepisosteus like the extant Lepisosteidae ( Lagler et al., 1942; Porter and Motta, 2004). Primary and secondary bony tissues show star-shaped osteocytes ( Fig. 6E View Figure 6 ), and they are crossed by canalicles, the so-called canalicles of Williamson ( Fig. 6C, E View Figure 6 ). Some of them can dichotomise. The presence of canalicles of Williamson is perfectly suited to the identification of † Nhanulepisosteus in the Lepisosteidae family.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.