Glis glis (Linnaeus, 1766)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6604339 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6604280 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9B215C43-FFCB-DD13-C9BD-FAAFFE25FE4F |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Glis glis |

| status |

|

17. View On

Fat Dormouse

French: Loir gris / German: Siebenschlafer / Spanish: Lirdn gris

Other common names: Edible Dormouse

Taxonomy. Sciurus glis Linnaeus, 1766 ,

“Habitat in Europa australi.” Restricted by C. Violani and B. Zava in 1994 to Southern Carniola, Slovenia.

More than 25 named forms have been proposed for populations of G. glis throughout its vast geographical distribution based on differences in coat color, size, cranial, and dental dimensions; historically, as many as 10-13 subspecies were recognized by J. R. Ellerman and T. C. S. Morrison-Scott in 1951, G. B. Corbet in 1978, and G. Storch in 1978. M. E. Holden in 2005 and B. Krystufek in 2010 highlighted the need for assessment ofintraspecific variation. A recent mtDNA phylogeographic study by H. Hiirner and colleagues in 2010 analyzed samples from 43 localities; the 16 haplotypes formed three well-supported genetic lineages that have nonoverlapping distributions, except for Sicily. Two genetic lineages were documented on Sicily, one ancestral lineage, plus one likely resulting from a more recent colonization. Other studies addressing intraspecific genetic and allozyme variation, such as those by S. E. Selcuk and colleagues in 2012, R. Colak and colleagues in 2008, and M. G. Filippucci and T. Kotsakis in 1994, similarly indicated that genetic data do not support traditionally recognized phenotypic subspecies. Hiirner and colleagues concluded that the European lineage of G. glis was characterized by widespread genetic homogeneity, suggesting a recent, rapid population expansion ¢.2000 years ago. Expansion ofthis species may have been linked with rapid spread of oak forests into northern Europe during the Holocene or, possibly, might have occurred or at least been aided by one or multiple introductions by humans during the Neolithic and more recent times, according to J.-D. Vigne in 1988, G. M. Carpaneto and M. Cristaldi in 1994, M. Sara in 2000, Hiirner and colleagues in 2010, and Selcuk and colleagues in 2012. Monotypic.

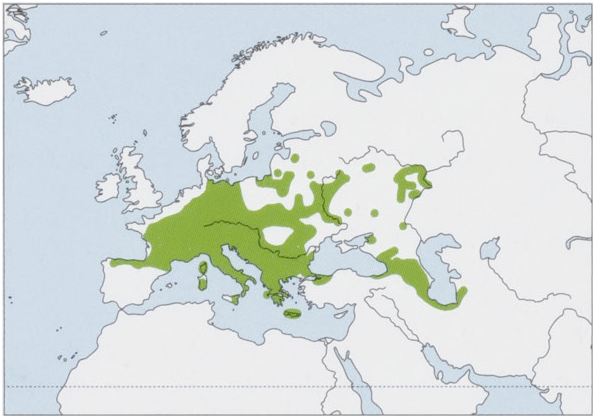

Distribution. W, C & SE Europe, from N Iberian Peninsula N to the Baltic States and Russia (excluding Denmark, the Atlantic coast of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France), S to Italy and SE Europe, and E to middle Volga River (Russia), NW Anatolia (Turkey), the Caucasus, N Iran, and SW Turkmenistan. Introduced population occurs in Great Britain. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 131-185 mm, tail 100-175 mm, ear 14-21-6 mm, hindfoot 18-2-33 mm; weight 79-140 g (adults after hibernation) and 105-228 g (adults before hibernation); some populations exhibit larger body size reaching a total length of 390 mm or even more, and individuals average smaller on northern and eastern peripheries of the distribution. The Fat Dormouse is the largest dormouse species and is squirrel-like in general form and appearance. Dorsal pelage is gray in young individuals but grayish brown in adults. Ventral pelage and inner surface of legs are white or yellowish. Tails are truncated by damage occasionally due to false tail autotomy. Tail color matches that of dorsal pelage and is uniform in color;tail is bushy and flattened dorsoventrally. A narrow dusky ring occurs around eyes. Ears are relatively short and rounded. Condylobasal length is 32-5—40-4 mm, zygomatic breadth is 20-25-7 mm, and upper tooth row length is 6-8 mm. Angular process of mandible is not perforated. External and cranial measurements for adults after the first hibernation are from former Czechoslovakia and Austria. Fat Dormice exhibit geographical variation in number of mammary glands from eight to 14. Chromosomal number is 2n = 62.

Habitat. Deciduous and mixed woodlands with high proportions of mast-producing beech ( Fagus ) or oak ( Quercus ) trees, both Fagaceae , from sea level to elevations of c.2000 m. Presence of other fruiting trees, such as hazel ( Corylus , Betulaceae ) and walnut ( Juglans , Juglandaceae ), improves habitat quality for Fat Dormice. They prefer mature forests stands with old hollow trees; hollows are used as nesting and breeding sites. Well-connected tree canopies are important for arboreal movements and protection from predators. Fat Dormice also occur in maquis (Mediterranean shrubland) on rocky areas along the Mediterranean coast. They often enter buildings and inhabit caves wherever present.

Food and Feeding. Fat Dormice predominantly feed on vegetation, and food of animal origin is supplementary. After emergence from hibernation, Fat Dormice feed on nuts and acorns from the previous year, inflorescences of various trees, vegetative parts of plants, and, to a lesser extent, foods of animal origin such as insects, adult birds, nestlings, and bird eggs. Berries and other soft fruits prevail in summer diets, and hard mast such as nuts and acorns are preferentially eaten in autumn. Across their entire distribution, Fat Dormice feed on more than 30 species of plants. For accumulation of fat reserves prior to hibernation, they feed mostly on beechnuts, hazelnuts, walnuts, and acorns. On northern and eastern peripheries of the distribution, extensive feeding on birch seeds ( Betula , Betulaceae ) occurs when these seeds are abundant.

Breeding. Fat Dormice give birth to one litter per year in July-August, coinciding with maximum food availability; however, individuals have been documented to completely skip reproduction in years with failure of beech or oak mast; males remain in a state of testicular regression. On the eastern periphery of the distribution, mass reabsorption of embryos was observed in females during years in which crop of oak mast was absent or scant. Fat Dormice usually breed every year in areas where food availability is more consistent. Gestation is c¢.25 days. Litter sizes are 1-13 young, and average litter size varies from 4-8 young to 7-9 young in different parts of the distribution. Females raise young without the help of males; at c¢.1-5 months old, juveniles begin to disperse from nests and live independently. Females reach sexual maturity after their first hibernation, but they usually start breeding at c.2 years old. Although a maximum life span of 14 years has been recorded in the wild, average life spans are 3-5 years; most females reproduce only once or twice in their lifetime.

Activity patterns. Fat Dormice are nocturnal and crepuscular, but diurnal activity is sometimes recorded in the afternoon, especially in spring and autumn. They may exhibit daily torpor during the active season, but this is uncommon in free-ranging individuals. Fat Dormice are obligate hibernators, and their hibernation period lasts 7-8 months in October—May on the northern periphery of the distribution but less than six months on the southern periphery. Before hibernation, Fat Dormice accumulate large quantities of body fat and rely entirely on this fat during hibernation. They typically hibernate in underground cavities 18-70 cm deep, with a median depth of 30 cm, without any nesting material. They sometimes hibernate in buildings and may also hibernate in caves. Summer dormancy or prolonged hibernation lasting up to 11-4 months was recorded in free-living Fat Dormice during a year of beech mast failure.

During hibernation, torpor bouts of up to 30 days are interrupted by arousals lasting several hours, with individuals normally remaining submerged in their hibernacula.

Body temperatures of hibernating Fat Dormice are close to soil temperatures.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Fat Dormice are arboreal and predominantly solitary. They are agile climbers, moving mainly in tree canopies and rarely descend to the ground. Their nests are typically situated in tree hollows, and they readily use nest boxes. Densities might reach 10-50 ind/ha in central and southern populations but only 1-5 ind/ha in northern populations. Female Fat Dormice maintain small exclusive home ranges, while males have much large overlapping home ranges.

Fat Dormice have a promiscuous mating system, in which females are territorial and non-territorial males compete for access to receptive females. Despite this competition, males can be found together in the same nest boxes in groups of 2-8 individuals during the mating season. Closely related females, usually mother and daughter, may share the same nest and nurse their young communally. Fat Dormice leave scent trails from scent glands on feet and circumanal glands around bases of their tails. They also deposit piles of droppings in latrines and on top of nest boxes. Fat Dormice produce the widest array of vocalizations among glirids, both in ultrasonic and audible ranges.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Fat Dormouse is common and widespread throughout most of its distribution. Conservation concerns are focused in the north-western part ofits distribution where populations are fragmented and densities are low (e.g. Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, and Belgium). Deforestation and particularly cutting of oak forests are main threats to the Fat Dormouse. A reintroduction program was initiated in Poland in 1997. In certain areas ofits distribution where Fat Dormice are abundant, they sporadically cause damage in silvicultural practice by stripping bark of European larch ( Larix decidua, Pinaceae ) and occasionally Norway spruce ( Picea abies), Scots pine (FP. sylvestris), and beech. They also may cause damage to orchard fruits such as apple, pear, peach, grape, hazel, Persian walnut,figs, and almond. They sometimes nest in human dwellings and may cause damage by gnawing woodwork or electric cables, and consume food stored in pantries. In Slovenia and Croatia, the Fat Dormouse is a game species that has been hunted traditionally.

Bibliography. Airapetyants (1983), Amori, Hutterer, Krystufek, Yigit, Mitsain, Munoz, Meinig & Juskaitis (2008), Andera (1986, 2011), Bieber & Ruf (2009), Carpaneto & Cristaldi (1994), Civitelli et al. (1994), Colak et al.

(2008), Corbet (1978), Donaurov et al. (1938), Ellerman & Morrison-Scott (1951), Fietz et al. (2009), Filippucci & Kotsakis (1994), Graphodatsky (2006), Grubesic et al. (2004), Hoelzl et al. (2015), Holden (1993, 2005), Hirner & Michaux (2009), Harner et al. (2010), Hutterer & Peters (2001), Jurczyszyn (1994, 2001, 2007), Juskaitis & Augute (2015), Juskaitis, Balciauskas, Baltrunaite & Augute (2015), JuSkaitis, Baltrunaite & Augute (2015), Konstantinov & Movchan (1985), Koren et al. (2015), KryStufek (1999a, 2004, 2010), Lebl et al. (2011), Lozan et al. (1990), Marteau & Sara (2015), Morris (1997a, 1997b, 2008, 2011), Naderi, Kaboli, Karami et al. (2014), Naderi, Kaboli, Koren et al. (2014), Pilastro et al. (2003), Rossolimo et al. (2001), Ruf et al. (2006), Sara (2000), Scinski & Borowski (2008), Sekeroglu & Sekeroglu (2011), Selcuk et al. (2012), Spitzenberger & Bauer (2001¢), Storch (1978), Trout et al. (2015), Vekhnik (2010, 2011), von Vietinghoff-Riesch (1960), Vigne (1988), Violani & Zava (1994), Zima et al. (1994).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.