Graphiurus angolensis, de Winton, 1897

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6604339 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6604254 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9B215C43-FFC7-DD07-CCC8-F59FFA9BF553 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Graphiurus angolensis |

| status |

|

4. View On

Angolan African Dormouse

Graphiurus angolensis View in CoL

French: Loir dAngola / German: Angola-Bilch / Spanish: Lirén de Angola

Taxonomy. Graphiurus angolensis de Winton, 1897 View in CoL ,

Caconda, Huila Plateau, southwestern Angola.

Placed in the subgenus Graphiurus . In 1939, G. M. Allen recognized G. angolensis as a valid species; however, J. R. Ellerman andcolleagues in 1953 listed it as a subspecies of G. platyops , and H. Genest-Villard in 1978 arranged G. angolensis as a subspecies of G. murinus . In 1974 and 1978, W. F. H. Ansell recognized that morphology and ecology of the north-western Zambian population of G. angolensis was distinct, although following Ellerman and colleagues, he considered the population to be a subspecies and identified it as G. platyops parvulus—a position followed by M. E. Holden in 1993. Subsequent study oflargeseries of specimens and preliminary multivariate analyses led Holden to conclude in 2005 and 2013 that these populations are consistently separable from G. platyops , G. rupicola , and G. murinus based on cranial morphology; she thus recognized G. angolensis as a valid species and agreed with Ansell’s hypothesis that these populations are probably aligned with G. microtis . Monotypic.

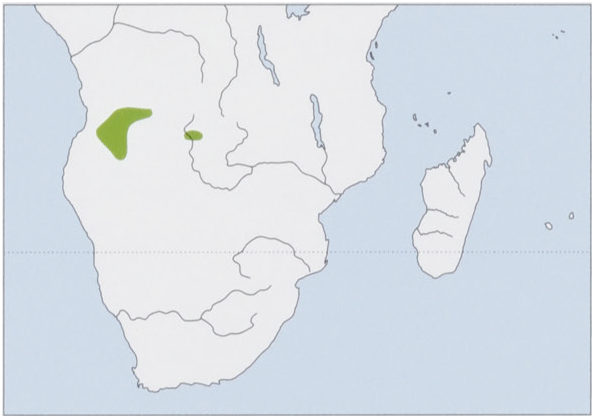

Distribution. C & SC Angola, and NW Zambia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 79-112 mm, tail 70-96 mm, ear 14-5-18 mm, hindfoot 17-20 mm. No specific data are available for body weight. No sexual dimorphism reported. Dorsal pelage of the Angolan African Dormouse varies from drab medium brown, medium brown with rufous or golden hue, to dark brown. Some individuals have darkening of dorsal pelage toward midline of head and back due to coalescence of dark guard hairs. Texture of dorsal pelage is soft,sleek, and thick; fur is moderately long (rump hairs 8 mm and guard hairs up to 12 mm). Ventral pelage white or cream lightly suffused with gray. Cheeks are cream or white, forming part of pale lateral stripe that extends from cheeks to shoulders. Sides of body appear paler, and dorsal pelage is clearly demarcated from ventral pelage. Head color matches that of dorsal pelage but becomesslightly paler toward snout. Most individuals have conspicuous eye mask that narrowly encircles eyes and extends from eyes to muzzle. Ears are brown, large, rounded, and usually accented by cream post-auricular patches. Hindfeet are white, or white with dark metatarsal streak, c.19% of head-body length. Tail is moderately long, ¢.80% of head—body length; tail hairs are shorter at base, 5—10 mm, and longerat tail tip, up to 33 mm. Tail color generally matches that of dorsal pelage, except that white hairs are mixed throughout length of tail. Tail tip is conspicuously white. Skull is long and robust, with highly inflated auditory bullae. Greatest length of skull is 26:3-30-8 mm, zygomatic breadth is 14-4-16-6 mm, upper tooth row length is 2:9-3-5 mm. External and cranial measurements are from specimens from Kabompo and Zambezi (formerly Balovale), Zambia. Chromosome number is not known, although karyotype of 2n = 54 recorded from Zambia may apply to the Angolan African Dormouse. Females have four pairs of nipples (I pectoral + 1 abdominal + 2 inguinal = 8).

Habitat. In Angola, many Angolan African Dormice have been collected from the Huila Plateau, an area that forms the Central Plateau Biogeographic Region comprised of moist, deciduous broadleaf woodlands and savannas dominated by trees such as miombo ( Brachystegia ), muchesa ( Julbernardia ), and doka ( Isoberlinia ), all Fabaceae , interspersed with grassland. Within this region, individuals were obtained in trees from localities in or near wetter miombo woodland of dry woodland interspersed with dambos (seasonally flooded grassy marshes or pans); some individuals were captured in abandoned beehives. In Zambia, specimen records indicate that most individuals were collected in wetter miombo woodland and dry evergreen broadleaf ( Cryptosepalum , Fabaceae ) forest. Individuals were also been captured in human dwellings. It occurs at elevations of 1000-2000 m.

Food and Feeding. The Angolan African Dormouse is probably omnivorous. One individual captured in Angola had eaten tree grubs and fruit of parasitic growth on trees and another was caught in a trap baited with meat.

Breeding. Littersize is probably 3-5 young. Young might be born in late February to early March.

Activity patterns. There is no information available for this species.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Angolan African Dormice are probably arboreal because most specimens have been captured in trees or in woodland. They are thought to be solitary except for females with lactating or recently weaned young. It has been stated that they are aggressive.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Data Deficient on The IUCN Red List. This classification of the Angolan African Dormouse is due to uncertainty about its taxonomic status, limits of its distribution, biology, and potential threats. It occurs in the Angolan Miombo Woodland ecoregion classified as vulnerable and in the Zambezian Cryptosepalum Dry Forest ecoregion classified as critical/endangered in 2015 by World Wildlife Fund; the two main evergreen Cryptosepalum forest blocks are located north and south of the Kabompo River, and together constitute the largest area of tropical evergreen forest in Africa outside the equatorial zone. Both ecoregions are sparsely inhabited by humans due to nutrient-poorsoils, but conservation in post-war Angola is low priority and inadequately funded. Populations of some large Angolan mammals had been decimated during the war; effects on small mammal populations have not been documented. Conservation and assessment efforts are hindered by poor security and presence of land mines. Fuel shortages have resulted in clear cutting of miombo woodlands for firewood and charcoal production.

Bibliography. Allen, G.M. (1939), Ansell (1963, 1974, 1978), du Bocage (1890), Chubb (1909), Coetzee et al. (2008a), Corti et al. (2005), Dean (2000), Ellerman et al. (1953), Genest-Villard (1978), Hill & Carter (1941), Holden (1993, 2005, 2013), Huntley & Matos (1992), Monard (1935), Rodrigues et al. (2015), White (1983), WWF (2015).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.