Gobiconodon sp.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/0003-0082(2001)348<0001:GFTECO>2.0.CO;2 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9A519862-FF93-FFFE-F61B-FD78FF16FD7A |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Gobiconodon sp. |

| status |

|

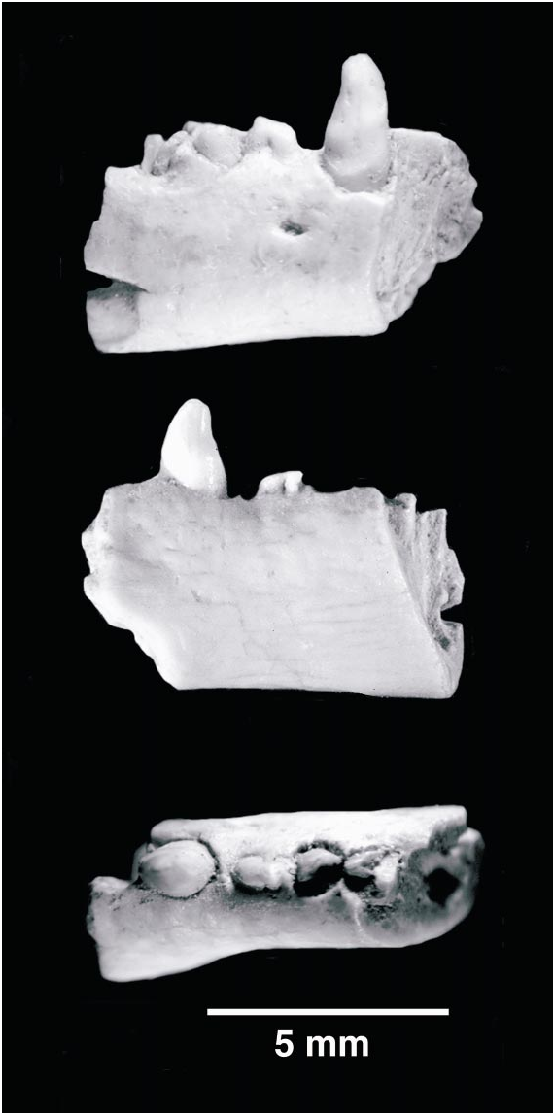

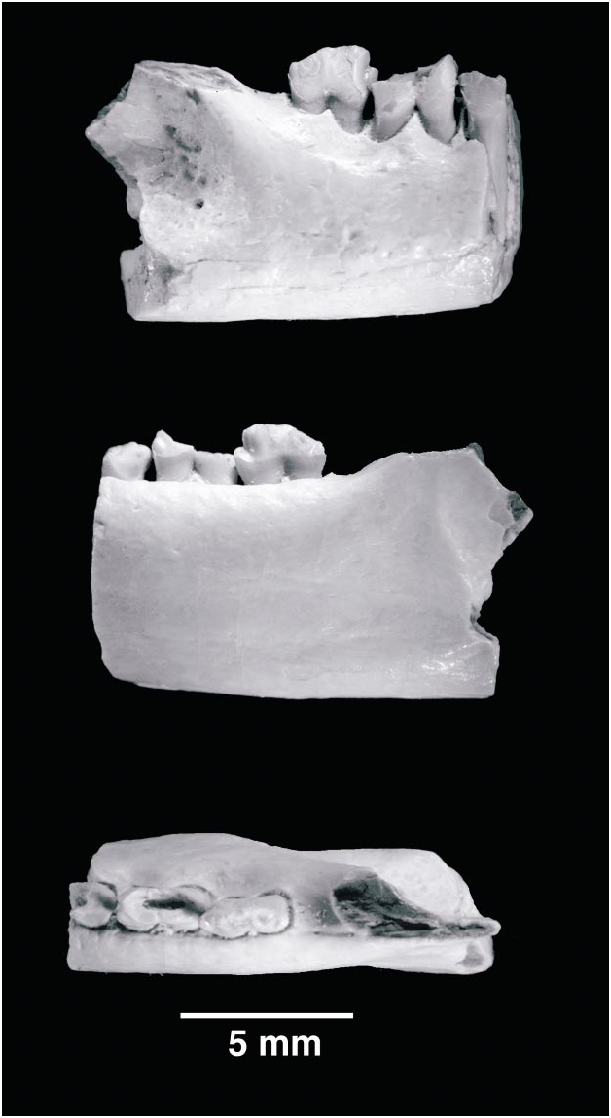

Figures 3 View Fig , 4 View Fig

Two specimens, PSSMAE 137 (fig. 3) and PSSMAE 138 (fig. 4), represent a second gobiconodontid taxon at Oshih. Both were found at the same locality where the lower jaw fragment of Gobiconodon hopsoni was discovered. These two specimens, the proximal and distal portions of a right lower jaw, were found a few inches away from each other and may belong to the same individual. One of the reviewers of an earlier version of this paper was concerned with the difference in size of the two fragments, which at first might mitigate against interpreting the fragments as one individual. However, the anterior portion of the jaw is much more slender than the posterior portion in some gobiconodontids, especially in G. ostromi (Jenkins and Schaff, 1988; fig. 5). We have matched both fragments of Gobiconodon sp. on the outline of G. ostromi (fig. 5). This illustration shows that the anterior fragment (PSSMAE 137) is about 10% smaller than expected if the proportions of G. ostromi are followed. The difference in size does not seem to preclude these two fragments being attributed to one specimen. If both fragments belong indeed to one individual, then the middle portion of the jaw bearing m2 and the mesial half of m3 has been lost (fig. 5). These fragments are slightly larger than corresponding portions of G. borissiaki , but smaller than those of G. ostromi .

The proximal fragment (PSSMAE 137) includes part of the symphysis, an incomplete alveolus similar to that of the caniniform p3, a complete caniniform p3, a small, doublerooted premolariform, and the roots of a large, doublerooted, probably molariform tooth.

According to the tooth identifications by Trofimov ( 1978), Jenkins and Schaff (1988), and KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg (1998), the first preserved alveolus corresponds to the p2. The alveolus suggests that the p2 was subequal in size to the following tooth, p3, but was placed more lingually in the jaw. Gobiconodontids show a great difference in height between the labial and lin gual margins of the anterior alveoli, particularly i1p2. Our specimen agrees well with the condition of other gobiconodontids. On the lingual aspect, the distalmost extent of the symphysial expansion is preserved, and no remnant of a Meckelian groove is discernible. The symphysis extends back to the level of the caniniform p3. The strong medial bulging of the symphysial area is also present in the other species of Gobiconodon and suggests that, as in other gobiconodontids, the symphysis was rather vertically oriented. Unfortunately, preservation is not sufficient to be certain about this feature. On the labial side, a small mental foramen is located at midmandibular height between the p3 and p4.

The p3 is a stout, erect caniniform tooth with a slightly flattened anterior surface and distinct wear facets on its labial surface. The apex is blunt, and two wear facets run posteroventrally on the labial surface of the tooth; a low ridge separates these facets. On the labial aspect of the tooth, a distinct ridge runs along the base of the crown and could be considered as a labial cingulum. However, when the alveolus was complete, this line was probably inside the alveolus and is more likely to correspond to the thickening of the roots at the alveolar level that we have observed in other gobiconodontids (see below) than to a true cingulum. Unlike Gobiconodon borissiaki , in Gobiconodon sp. the p3 lacks accessory cusps; only the central cusp, likely serially homologous to a, is present on the crown. As with p2, the lingual wall of the alveolus for the p3 is much taller than the labial wall.

The p4 is very small and separated from the p3 by a short diastema. Both p3 and the restored m1 tower over the minute premolariform. The p4 has two subequal roots that are fused, or nearly fused, to the alveolus. If there was any periodontal ligament, it was negligible. Heavy wear, oriented mesiolabially, obscures crown features of this small tooth. Nevertheless, what remains suggests that a main central cusp was present, possibly accompanied by small mesial and distal accessory cuspules. Only the roots of the m1 are present. They are subequal in size, but differ in cross section; the mesial root is subcircular, while the distal root is more angular.

The alveolus for the anterior root of the m2 is preserved in PSSMAE 137. The alveolus suggests that the m2 was subequal to m1 or perhaps marginally larger. The anterior root would slant posteriorly a little.

The second fragment, PSSMAE 138, includes the posterior root of the m3, m4m5, and the anterior portion of the masseteric fossa (fig. 4). On the posterior root of the m3, only the sharp distal edge of cusp d is preserved. This cusp fits snugly in the notched mesial aspect of the m4. The notch on the m4 is formed by a low, but distinct, cusp e and the anterior surface of b. KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg (1998) reported that in Gobiconodon hoburensis the contact between succeeding teeth is formed by cusp d fitting between a mesiolingual cusp e and a mesiolabial cusp f. A cusp f, however, seems to be very small and rapidly eroded or missing altogether. Cusp d is supported labially by the anterior slope of b. The remaining cusps of the crown are missing.

The m5 is the best preserved molariform of this jaw fragment. The contact between m4 and m5 is different from that between m3 and m4. The distal cusp d of the m4 does not fit in an embrasure between cusp e and the anterior slope of b, or possibly cusp f. A mesiobuccal cusp or extension of the crown is absent, and cusp d abuts directly labial to cusp e. Cusp b is away from the front of the tooth and a cusp f is absent; cusp e, however, is prominent. In short, m4 does not interlock with m5, but is arranged en echelon. In all other species of Gobiconodon , cusp d of the m4 interlocks with cusp e and either the slope of b or cusp f (KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg, 1998: fig. 7). All the remaining major cusps of the m5 are damaged and worn, but enough remains to show that they were essentially aligned anteroposteriorly. On the lingual side of the m5, a moderate cingulum runs from cusp e to cusp d. The roots of the molariforms do not show the thickening at the level of the alveolus present in G. borissiaki and the fragmentary lower jaw referred to G. hopsoni . The roots of the m5 are directed less distally than those of the m5 of the Asiatic species of Gobiconodon (KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg, 1998; personal obs.) and are more similar to those of G. ostromi (Jenkins and Schaff, 1988) .

The dentary is robust, with thick cortical bony walls that are thicker than those of Gobiconodon borissiaki . The masseteric fossa is the most conspicuous feature on the labial surface of the dentary; it is moderately deep and limited ventrally by a thick and blunt masseteric ridge. This fossa extends anteriorly, but stays behind the level of the m5. The anterior limit of the fossa was formed by a mostly missing coronoid ridge. In the anterior part of the masseteric fossa, a small foramen opens into the substance of the dentary. This foramen occupies a position similar to the masseteric foramen, or labial mandibular foramen, of other Mesozoic mammals (Dashzeveg and KielanJaworowska, 1984; Rougier, 1993; Cifelli et al., 1998).

On the labial aspect of the body of the jaw, between the lower molariforms, conspicuous depressions corresponding to the position of the upper molariforms can be identified. Similar depressions are present in Gobiconodon ostromi , but not in the remaining Asiatic species, and these may simply be related to the larger size of G. ostromi and G. hopsoni .

On the lingual aspect of the dentary, a very subtle sulcus runs mesiodistally along the ventral third of the dentary toward the broken edge of the mandibular foramen. This sulcus is the impression of the remnant of Meckel’s cartilage. It is less pronounced than in other species of Gobiconodon . The mandibular foramen is very posteriorly placed and marks the anterior edge of the pterygoid fossa. The mesialmost edge of this fossa extends mesiodorsally from the foramen in the broken base of the coronoid process. An incomplete oval depression lies ventral to the mandibular foramen, a muscle scar likely produced by the medial pterygoid (fig. 4). This depression is known in all species of Gobiconodon , but not in other Mesozoic mammals, and is a good diagnostic feature for this group.

The last molariform in Gobiconodon sp. is located well in front of the anterior edge of the masseteric fossa, and the molariform alveolus is directly at the base of the coronoid process. The m5 is also close to the base of the coronoid process in G. hoburensis , but not in described specimens of G. borissiaki or G. ostromi . In the latter two taxa, there is a space between the last molariform and the origin of the coronoid process (Trofimov, 1978: fig. 1; Jenkins and Schaff, 1988: figs. 4, 6). The masseteric fossa in G. ostromi and G. borissiaki extends anteriorly to at least the level of m5 (KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg, 1998). However, a specimen of G. borissiaki (PSSMAE 143) collected recently in Khoobur by the AMNH–Mongolian Academy of Sciences Expeditions shows an empty alveolus for a doublerooted tooth at the base of the coronoid process. Consequently, in this specimen there is no space between the back edge of the alveolus and the anterior aspect of the masseteric ridge. It is possible that the differences in this character between specimens of G. borissiaki may be explained by differences in ages of the specimens, as also suggested by KielanJaworowska and Dashzeveg (1998). Juvenile or young individuals have a shorter jaw than do adults, but tooth crowns do not grow after eruption. Therefore, the teeth are closer to the coronoid process or even medial to it in young specimens of other mammals. The jaw PSS MAE 143 shows little or no wear on cusp a or the distal half of the freshly erupted m4, suggesting that the specimen is a young adult and supporting the idea of ontogenetic change in relative position of the molariforms and coronoid process. The similarities in the position of the last molariform and coronoid process in the fragment of Gobiconodon sp. (PSSMAE 138) and G. hoburensis are probably of little consequence.

If the two fragments of Gobiconodon sp. described above (PSSMAE 137 and 138) do belong to the same individual, the jaw should rapidly decrease in height anteriorly, as is suggested by the match of the fragments of Gobiconodon sp. on the outline of G. ostromi (fig. 5). The other species of Gobiconodon do not show the same anterior tapering of the dentary.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.