Typhloiulus rhodopinus, Vagalinski, Boyan, Stoev, Pavel & Enghoff, Henrik, 2015

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3999.3.2 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F91C0D00-FC34-4D42-9B2F-D7BE686291F6 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5664874 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/990B87FC-3477-322D-FF43-7D18FEBE7A6F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Typhloiulus rhodopinus |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Typhloiulus rhodopinus View in CoL sp. n.

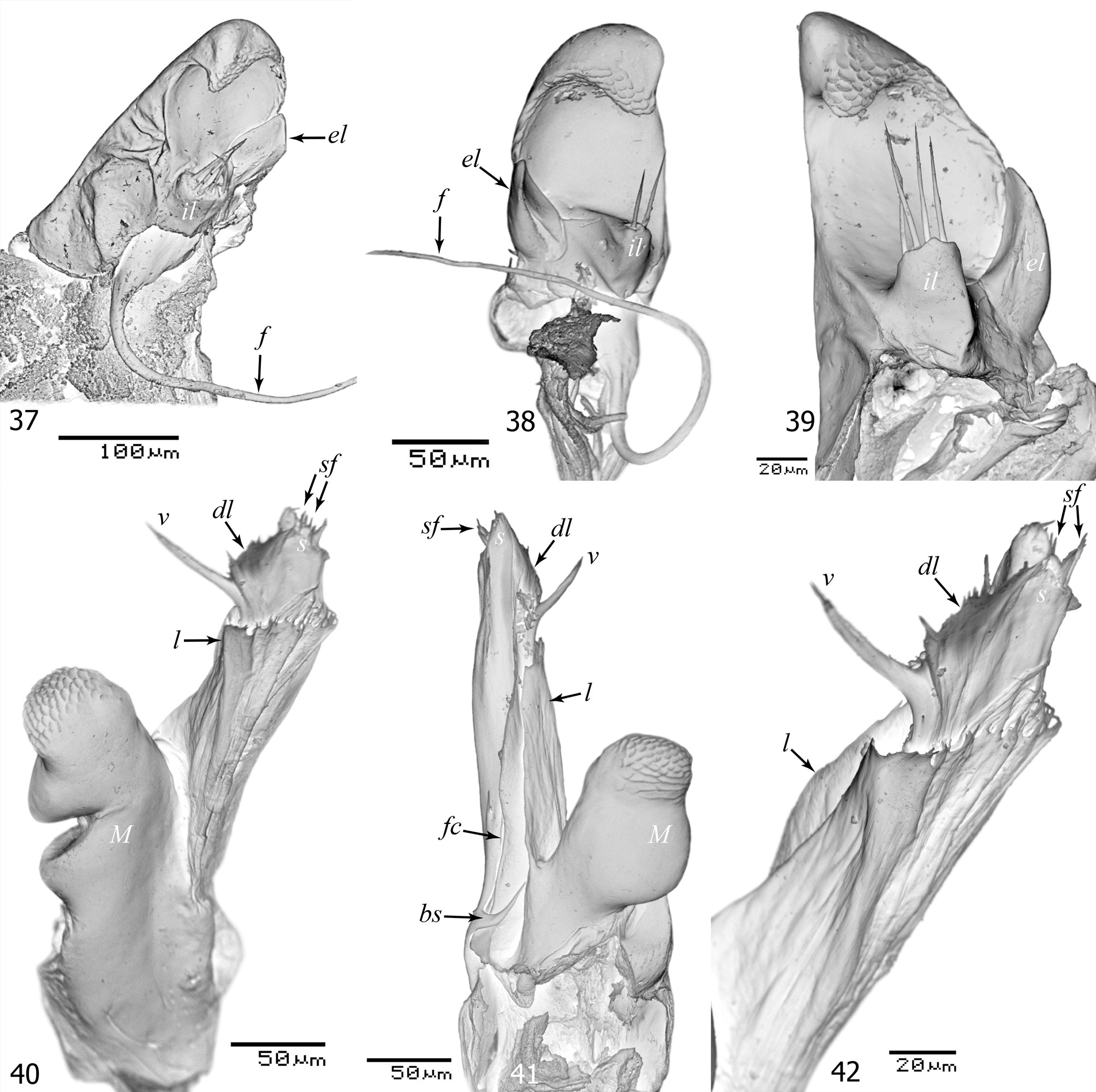

Figs 30–48 View FIGURES 30 – 36 View FIGURES 37 – 42 View FIGURES 43 – 48

Material. Holotype ♂ (intact) ( NMNHS), Bulgaria, East Rhodopi Mts., E of Madzharovo, abandoned mine gallery on the left bank of River Arda, 15.V.1996, B. Petrov leg.

Paratypes: 1 ♂ broken into 2 pieces, gonopods dissected ( ZMUC), same locality and collecting data as of the holotype; 3 ♂ ( NMNHS) (one gonopod mounted for SEM, second gonopod missing), Bulgaria, East Rhodopi Mts., Madzharovo Distr., abandoned mine gallery, 2 km from Madzharovo, road to v. Borislavtsi, below the road, decayed wood, 20.IV.1996, P. Stoev & B. Petrov leg.; 2 ♀ (1 broken into 2 pieces, with dissected vulvae, left vulva mounted for SEM; second specimen broken into 2 pieces, not dissected) ( NMNHS), same locality and collecting data; 1 intact ♀ ( ZMUC), same locality and collecting data; 4 ♂ (1 intact specimen, 2 broken into 2 pieces, 1 broken into 3 pieces, with dissected gonopods), 4 ♀ (all broken into 2 or more pieces) ( NMNHS), Bulgaria, East Rhodopi Mts., Lyubimets Distr., abandoned mine gallery between v. Lozen and v. Cherna mogila, 4.XI.1999, B. Petrov, S. Beshkov & D. Vasilev leg.; 3 ♂ (2 dissected), 7 ♀ ( ZMUC), same locality, rotten log, 12.IV.1998, B. Petrov & B. Barov leg.; 2 ♂ (1 intact, second one broken into 3 pieces, penis dissected, gonopods mounted for SEM) ( NMNHS), Greece, Evros Distr., v. Avas, cave Avanos, 17.V.1987, P. Beron leg.

Additional material. Bulgaria: 4 juv. ( NMNHS), East Rhodopi Mts., Madzharovo Distr., abandoned mine gallery, 2 km from Madzharovo, road to Borislavtsi, below the road, decayed wood, 20.IV.1996, P. Stoev & B. Petrov leg.; 1 ♀ ( NMNHS), Kardzhali Distr., v. Oreshari, cave Razklonenata, 3.IV.1992, B. Petrov leg.; 4 ♀ ( NMNHS), Ivailovgrad Distr., cave Dupkata, 27.IV.1995, B. Petrov leg.; 2 ♂ ( ZMUC); same locality, 23.IV.1996, B. Petrov & P. Stoev leg.; 1 ♀, 1 subad. ♂ ( NMNHS), East Rhodopi Mts., Haskovo Distr., v. Dolno Cherkovishte, cave Zandana, 21.IV.1996, B. Petrov & P. Stoev leg.; 1 ♀ ( NMNHS), East Rhodopi Mts., Momchilgrad Distr., v. Kremen, cave Zlatnata yama, 27.IV.1996, P. Stoev & B. Petrov leg.; 1 ♂, 1 ♀ ( NMNHS), East Rhodopi Mts., abandoned mine gallery at the base of Kovan kaya near v. Dolno Cherkovishte, rotten log, 13.IV.1998, B. Petrov leg. Greece: 2 ♂ (1 pair of gonopods mounted for SEM), 1 ♀ ( ZMUC), Thrace, Nomos Evros, 20 km SW Dhadhia [Dadia], 80 m, stream, oak forest, 21.IV.1994, leg. W. Schawaller, H. Schmalfuss ded. 1994.

Diagnosis. T. rhodopinus sp. n. is morphologically similar to T. albanicus and T. giganteus . However, it can be readily distinguished by a combination of certain gonopodal and external body characters (see Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

Etymology. Named after the Rhodopi Mts., the main distribution area and type locality of the species. Adjective.

Description. Holotype with 52+3+T body rings, l = 24 mm, h = 1.3 mm. Paratype males with 49–63 podous body rings, with 1–3 apodous rings, l = 17–37 mm, h = 1–1.65 mm. Paratype females with 64–72 podous body rings, with 1–2 apodous rings, l = 22–34 mm, h = 1.1–1.65 mm.

Colouration: light to dark brownish-beige, prozonae darker than metazonae, legs and antennae yellowish beige to light brown.

External structures: 4 supralabral (a central 5th seta present in one male, probably an aberration) and 14–16 labral setae. Labrum tridentate. Antennomeres 2, 3, 4 and 5 more or less equally long, somewhat longer than 6th; antennomere 5 with a dense whorl of sensilla basiconica (somewhat smaller than 4 sensilla at antennal apex) dorsally and laterally; a similarly dense whorl of very small sensilla present on antennomere 6. Male mandibular stipites not enlarged. Gnathochilarium of normal julid appearance, with 3 apical setae on each stipes, and with 5 setae in a row on each lingual plate; promentum 0.5–0.53 times as long as lingual plates, length to width ratio: 1.6– 1.8. Collum smooth, with several shallow, parallel striae at postero-lateral corner. Prozonae smooth. Metazonae with mostly straight, parallel striae, with 5–7 striae in a square with sides equal to metazonal length just below ozopore level; a dense whorl of erect setae, ca 3/5 to equal to metazonal length at metazonal hind margin. Ozopores placed behind pro-metazonal suture at ca 1/5–2/5 of metazonal length. Telson ( Fig. 31 View FIGURES 30 – 36 ): preanal process moderately long, pointed, curved downwards, rather wedge- than roof-shaped, slightly surpassed by longest anal setae; several long setae present on its upper side. Subanal scale very short, rounded, not protruding behind rear contour of anal valves, with 2 rows of setae: a marginal row of 10–12 setae and an inner row of 5 setae. Anal valves densely pilose. Male pleurotergum 7 ( Fig. 32 View FIGURES 30 – 36 ) ventrally with rounded protrusions directed ventro-posteriad. Male leg-pair 1 ( Fig. 33 View FIGURES 30 – 36 ) normal hooks, slightly turned upwards, with or without a minute tarsal remnant. Male legs in anterior part of body ( Figs 34 & 35 View FIGURES 30 – 36 ) without adhesive pads, but with a pit (p) both on postfemur and tibia. Tarsus of male mid-body leg 1.6–1.8 times longer than tibia, and 3 times longer than apical claw.

Penis ( Fig. 36 View FIGURES 30 – 36 ): elongated trapezoidal, with moderately long, mostly parallel apical lobes (al) ending with long, tapering, somewhat converging terminal lamellae (tl).

Gonopods ( Figs 37–47 View FIGURES 37 – 42 View FIGURES 43 – 48 ): Compact, in situ entirely concealed inside gonopodal sinus, promere covering tip of mesomere, opisthomere considerably outreaching both pro- and mesomere. Promere ( Figs 37–39 View FIGURES 37 – 42 ) somewhat higher than broad, with a convex lateral margin, a straight to slightly concave mesal margin and a rounded apex, strongly bent posteriad; apex and distal part of lateral margin with a tuberculate surface; parabasal internal lobe (il) short, edgy, with 2–4 apical setae; parabasal external lobe (el) elongated, distally tapering, somewhat outreaching internal one. Flagellum (f) thin, except for a very thick basal part, nearly 1.5 times longer than promere. Mesomere (M in Figs 40, 41 View FIGURES 37 – 42 & 43–46 View FIGURES 43 – 48 ) rather short and robust, bulging, with a tuberculate apical surface. Opisthomere ( Figs 40–47 View FIGURES 37 – 42 View FIGURES 43 – 48 ) with a slightly convex posterior margin, without processes; basal spine (bs) crescent-like bent; single, smaller spines present distally behind flagellum channel (fc); intermediate lamella (l) well-developed, weakly to moderately pronounced, reaching ca 2/3 of opisthomere height; velum (v) unipartite, thin, pointed, slightly to strongly bent distad; a jagged distal lamella (dl) between velum and solenomere; solenomere (s) short, with a flat, posteriorly oblique apex, with a dense row of seti-form filaments (sf).

Vulva ( Fig. 48 View FIGURES 43 – 48 ): Somewhat compressed antero-caudally, mostly symmetric, mesal valve slightly broader than lateral one. Opening (o) elongated, cleft-like, nearly reaching bursal base. 4 setae in a vertical row on each valve. Operculum (op) considerably higher than bursa, broadly convex, with 4 vertical rows of 4–5 setae each. Receptaculum seminis consisting of a moderately thick central tube (ct) not forming a distinct central ampulla and of a thin, somewhat folded posterior tube (pt) ending into an egg-shaped posterior ampulla (pa).

Remarks. The examined material shows moderate variation in certain morphological characters. Morphologically the most aberrant is the population from the vicinity of Lyubimets which, unlike all remaining specimens examined, possesses 14 instead of 16 labral setae, and a considerably more strongly bent velum of the opisthomere. Also noteworthy are the observed size differences, the specimens from Greece being considerably larger than those from Bulgaria. Colouration seems to vary as well both in intensity and tincture. However, the above-mentioned differences are not sufficient to justify the erection of new subspecies, let alone more than one species.

Ćurčić et al. (2003) emphasized the similarity between T. albanicus and T. giganteus . T. rhodopinus sp. n. obviously belongs to the same species-group characterized by an opisthomere with a well-developed, but not conspicuously pronounced intermediate lamella, a slender, unipartite, spine-like velum, a jagged distal lamella between the velum and the solenomere; and a slender penis with converging sides, deeply divided apical lobes and long, parallel or converging terminal lamellae. The group is so far confined to the central and eastern parts of the Balkan Peninsula.

Typhloiulus View in CoL is one of the well-defined genera of Julidae View in CoL which shows a considerable number of distinctive characters, as already listed in the beginning of the systematic part. However, the grouping of species within Typhloiulus View in CoL is far from settled. Many, often controversial, subgenera have been introduced in an attempt to resolve the intrageneric systematics. Two major, presumably natural, well defined groups appear from among the 33–36 presently known species. These are the subgenera Typhloiulus sensu stricto and Stygiiulus Verhoeff, 1929 . Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str. was properly characterized by Strasser (1962, 1966). It comprises 15 unquestionable species: T. albanicus View in CoL , T. bureschi View in CoL , T. ganglbaueri View in CoL , T. georgievi View in CoL , T. giganteus View in CoL , T. hauseri View in CoL , T. incurvatus View in CoL , T. kotelensis View in CoL , T. longinquus View in CoL , T. nevoi View in CoL , T. psilonotus View in CoL , T. serborum View in CoL , T. strictus View in CoL , T. orpheus View in CoL sp. n. and T. rhodopinus View in CoL sp. n. They all share a very similar gonopod conformation, and the group is further supported by certain external characters, such as: male leg-pair 1 typically hook-shaped (except for the known males of T. ganglbaueri View in CoL ), the femora of male legs in the anterior part of the body without modifications on their ventral surface, the ozopores located closely behind the suture, and the preanal process straight or bent downwards. The distribution of Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str. is mostly confined to the Balkan Peninsula, with several species expanding to the Carpathians and the Apennine Peninsula. In having a more elongated pro- and mesomere, the position of T. beroni View in CoL , (from eastern Albania) in relation to this group needs still to be clarified. The position of T. bosniensis View in CoL likewise remains unclear: this species lacks an intermediate lamella between the meso- and opisthomere. On the other hand, both latter species agree in all remaining diagnostic characters of Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str.

The intermediate lamella attracts attention as a potentially important phylogenetic character within Typhloiulus View in CoL and the “Typhloiulini” in a broader sense. Apart from the members of Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str., the “typhloiuline” genus Lamellotyphlus Tabacaru, 1976 View in CoL displays a particularly strongly developed lamella which is completely fused with the mesomere. Enghoff (1987) suggested that such a lamella may represent a transitional evolutionary stage towards the true pro-mesomeral forceps seen in the “higher julids”, and placed the genus in the tribe Leucogeorgiini which is characterized by such an intermediate gonopod conformation. If this is true, then Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str. should be the most plesiotypic/basal group within the genus, and the entire genus Typhloiulus View in CoL as understood here, possibly subdivided into several monophyletic genera, and possibly together with some other related genera, should be placed near the base of the “higher julids”. However, Makarov et al. (2003) argued that the lamella in Lamellotyphlus View in CoL seems not to be homologous with that observed in the Leucogeorgiini, suggesting instead that it may be a secondary structure leading to a gradual fusion between the already differentiated meso- and opisthomere; this is most evident in the monotypic genus Banatoiulus Tabacaru, 1985 View in CoL , from Romania.

Strasser (1962) listed four species in the subgenus Stygiiulus : T. illyricus View in CoL , T. ausugi View in CoL , T. maximus and T. montellensis View in CoL . T. tobias View in CoL seems to be another good candidate member of this group, although slightly deviating in its gonopodal features from the remaining species. The five species can be referred to as “the Alpine group”, considering their compact distribution in the southeastern foothills of the Alps.

Spelaeoblaniulus Ceuca, 1956 View in CoL , is another distinctive subgenus which comprises one species, T. serbani View in CoL , that possesses a very unusual opisthomere with a large, finely striated, microspinose solenomere, a vestigal velum and a conspicuous posterior process. T. motasi View in CoL perhaps belongs to the same lineage given its morphological similarity to T. serbani ( Tabacaru & Gava 1992) View in CoL . Their distribution in the Carpathian region provides further support of such an assumption.

The remaining subgenera are mostly weakly defined, inappropriately used or even invalidly proposed, and thus can hardly be applied to the current systematics of Typhloiulus View in CoL .

The subgenus Allotyphloiulus Verhoeff, 1905 View in CoL , was erected to encompass the blind Cylindroiulus vulnerarius (Berlese, 1888) View in CoL alone. For reasons hard to explain, Loksa (1960) found his newly described Typhloiulus polypodus View in CoL to be most similar to the above cylindroiuline species and assigned it to the same subgenus.

Haploprotopus Verhoeff, 1899 , includes only T. ganglbaueri View in CoL . Although Strasser (1962) recognized the subgenus, he did not consider it justified, since the gonopods of T. ganglbaueri View in CoL are typical of T. s. str., and the only definitive character of the subgenus, the unmodified male leg-pair 1 as described by Verhoeff (1899) from 3 topotypic males, is more likely evidence of “junior males” (see below for explanation) than of an outstanding member of Typhloiulus View in CoL .

Two species were assigned to Inversotyphlus Strasser, 1962 , T. lobifer View in CoL and T. longipes View in CoL . Both share an anteriorly bent promere, the main character that defines the subgenus, but differ significantly in a number of other features. On the other hand, T. lobifer View in CoL is similar to T. gellianae View in CoL , as already noted by Makarov et al. (2006).

Mesoporoiulus Verhoeff, 1905 , was invalidly proposed without a type species. Later Jeekel (1971) designated Typhloiulus roettgeni (described on the basis of a female, of a dubious status, but tentatively considered as a synonym of Trogloiulus boldorii View in CoL ) as the type species.

Attems (1959) listed 5 species: T. albanicus View in CoL , T. incurvatus View in CoL , T. bureschi View in CoL , T. psilonotus View in CoL and T. kotelensis View in CoL , in his newly defined subgenus Smeringolophus . However, all of these are recognized as members of Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str. T. psilonotus View in CoL is furthermore the only species in the subgenus Xestotyphloiulus Verhoeff, 1899 .

Not only the taxonomy of Typhloiulus View in CoL , but also its monophyly is somewhat questionable. As for many other julid genera, the pioneer researchers used very broad defining concepts compared to the present-day systematic standards. This has resulted in many significantly diverse species to have been treated under Typhloiulus View in CoL , (almost) solely based on the lack of ocelli. Some of them, like e.g. Apfelbeckiella trnowensis (Verhoeff, 1928) View in CoL and Elbaiulus chrysopygus (Berlese, 1888) View in CoL , are today considered as hardly at all related to the Typhloiulini/ Leptoiulini View in CoL . A number of other species from the “typhloiuline” group have been transferred to other genera, due to certain morphological differences, these mostly concerning the gonopodal apparatus.

However, even after those taxonomic changes, Typhloiulus View in CoL looks too much like a heterogenous assemblage. Part of the problems lie in the rather unsatisfactory diagnoses of some of the other “typhloiuline” genera. The absence of a flagellum is in fact the only character that separates Serboiulus Strasser, 1962 View in CoL , and Trogloiulus Manfredi, 1931 View in CoL , from Typhloiulus View in CoL . Being a reductive character that has arisen independently many times in the evolution of Julidae View in CoL , its phylogenetic weight is low. Moreover, members of Stygiiulus seem to have more in common with Trogloiulus View in CoL , both in gonopodal and external features, than with their nominal congeners. In the light of this observation, the southern Alpine distribution of both Stygiiulus and Trogloiulus View in CoL may be the result of common origins, and the loss of the flagellum might have subsequently occurred in some of the descendants. Aberrant species like, e.g., T. longipes View in CoL , T. motasi View in CoL and T. serbani View in CoL , further strengthen the impression that we are dealing with a para-/polyphyletic genus.

At present, the usage of the tribe Typhloiulini to encompass all blind julid genera possessing a pro-mesomerital forceps and a more or less well-differentiated velum of the opisthomere seems to lack a solid ground. Mauriès et al. (1997) regarded Typhloiulini as a “highly suspicious taxon”, emphasizing the impossibility to delimit it from the Leptoiulini View in CoL in terms of gonopod characteristics. The two species of the genus Leptotyphloiulus Verhoeff, 1899 View in CoL , which, apart from lacking ocelli, possess gonopod features of a proper Leptoiulus View in CoL type, are a good example of that. Indeed, the existence of Leptotyphloiulus View in CoL alone is evidence of polyphyletic origins of the Typhloiulini. None of the remaining mono- or oligotypic “typhloiuline” genera, viz., Serboiulus View in CoL , Trogloiulus View in CoL , Alpityphlus (see above under Typhloiulus seewaldi View in CoL ), Buchneria Verhoeff, 1941 View in CoL , Leptotyphloiulus View in CoL , Banatoiulus View in CoL and Lamellotyphlus View in CoL , looks more similar to Typhloiulus View in CoL s. str. than the latter looks similar to each of the ocellate genera Leptoiulus Verhoeff, 1894 View in CoL , Xestoiulus Verhoeff, 1893 View in CoL or Ophyiulus Berlese, 1884 View in CoL . It thus appears logical to assume the presence of two or more lineages within a larger tribe Leptoiulini View in CoL that may have independently taken parallel evolutionary courses towards troglo-, geo- or petrophilic modes of life, this leading to adaptations like reduction of ocelli, pale body colour, dense and long setation, and long legs and antennae.

There is, however, some evidence that at least some of these blind taxa may constitute a monophyletic group beyond the Leptoiulini View in CoL . The molecular phylogeny of Enghoff et al. (2013) puts T. orpheus View in CoL sp. n. (cited as Typhloiulus View in CoL n. sp.) in an isolated clade, away from the genera Julus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL , Pacifiiulus Mikhaljova, 1982 View in CoL , Leptoiulus View in CoL , Xestoiulus View in CoL and Ophyiulus View in CoL , that appear on the tree in a robust monophyletic clade.

The unusual ‘premature’ acquisition of morphological sexual maturity observed in males of some “typhloiuline” taxa add support to the natural ‘identity’ of the tribe in one or another generic composition. The phenomenon is known as “junior males” ( Strasser 1971b, see also Enghoff et al. 1993) in which the first leg-pair is unmodified or only partly modified, while the gonopods are (almost) fully developed, but are sometimes entirely protruding outside the gonopodal sinus. The term was coined by Strasser (1971b) as “Junior-Männchen” on the basis of specimens of T. illyricus View in CoL and Serboiulus deelemanni View in CoL ; we have observed junior males in Serboiulus spelaeophilus View in CoL and Typhloiulus bureschi View in CoL , and the same phenomenon probably concerns T. ganglbaueri View in CoL . The adult males of these species have almost fully concealed gonopods and typical hook-like first leg-pair.

In any case, the systematics of the seemingly related and more or less overlapping tribes Typhloiulini, Leptoiulini View in CoL and Julini View in CoL present a tough riddle. Unravelling the phylogeny of Typhloiulus View in CoL , together with the other, aberrant blind genera, is inevitably related to a detailed revision of Leptoiulini View in CoL , especially of the speciose and notoriously problematical genus Leptoiulus View in CoL .

The presently known somewhat more than 30 species of Typhloiulus View in CoL are surely far below the real number of existing species. Many more are yet to be discovered, especially from undersampled areas in Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and, especially, Croatia, the latter the country in the Balkan Peninsula the richest in caves. Besides this, data on the distribution of most species is still insufficient, with nearly one-third so far known only from their type localities. Future studies would shrink these gaps in our knowledge and allow for better founded considerations on the systematic position and biogeographic affinities of the genus to be made.

TABLE 1. Diagnostic characters of T. albanicus, T. giganteus and T. rhodopinus.

| setae on subanal scale | 2 marginal | in 2 rows: 7 marginal and 3 submarginal | in 2 rows: 10–12 marginal and 5 submarginal |

|---|---|---|---|

| protrusions of the ventral margins of male pleurotergum 7 | pointed | rounded | rounded |

| male walking legs in anterior part of body | adhesive pad on tibia, no modifications on postfemur | adhesive pad on tibia and a pit on postfemur | pit on both tibia and postfemur |

| distal lamella of opisthomere | small, considerably lower than the tip of solenomere | small, considerably lower than the tip of solenomere | pronounced, almost reaching the tip of solenomere |

| Discussion |

| ZMUC |

Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Typhloiulus rhodopinus

| Vagalinski, Boyan, Stoev, Pavel & Enghoff, Henrik 2015 |

T. serbani (

| Tabacaru & Gava 1992 |

Banatoiulus

| Tabacaru 1985 |

Pacifiiulus

| Mikhaljova 1982 |

Lamellotyphlus

| Tabacaru 1976 |

Inversotyphlus

| Strasser 1962 |

Serboiulus

| Strasser 1962 |

Spelaeoblaniulus

| Ceuca 1956 |

Buchneria

| Verhoeff 1941 |

Trogloiulus

| Manfredi 1931 |

Stygiiulus

| Verhoeff 1929 |

Apfelbeckiella trnowensis

| Verhoeff 1928 |

Allotyphloiulus

| Verhoeff 1905 |

Mesoporoiulus

| Verhoeff 1905 |

Haploprotopus

| Verhoeff 1899 |

Xestotyphloiulus

| Verhoeff 1899 |

Leptotyphloiulus

| Verhoeff 1899 |

Leptoiulus

| Verhoeff 1894 |

Xestoiulus

| Verhoeff 1893 |

Cylindroiulus vulnerarius

| Berlese 1888 |

Elbaiulus chrysopygus

| Berlese 1888 |

Ophyiulus

| Berlese 1884 |

Julus

| Linnaeus 1758 |