Sclerasterias sp.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5138.5.2 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D5B670F9-1153-4C17-A642-CA61C7EA1A06 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6596073 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/961187F7-EB14-FFF8-F5DB-FE9234EE2AE7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Sclerasterias sp. |

| status |

|

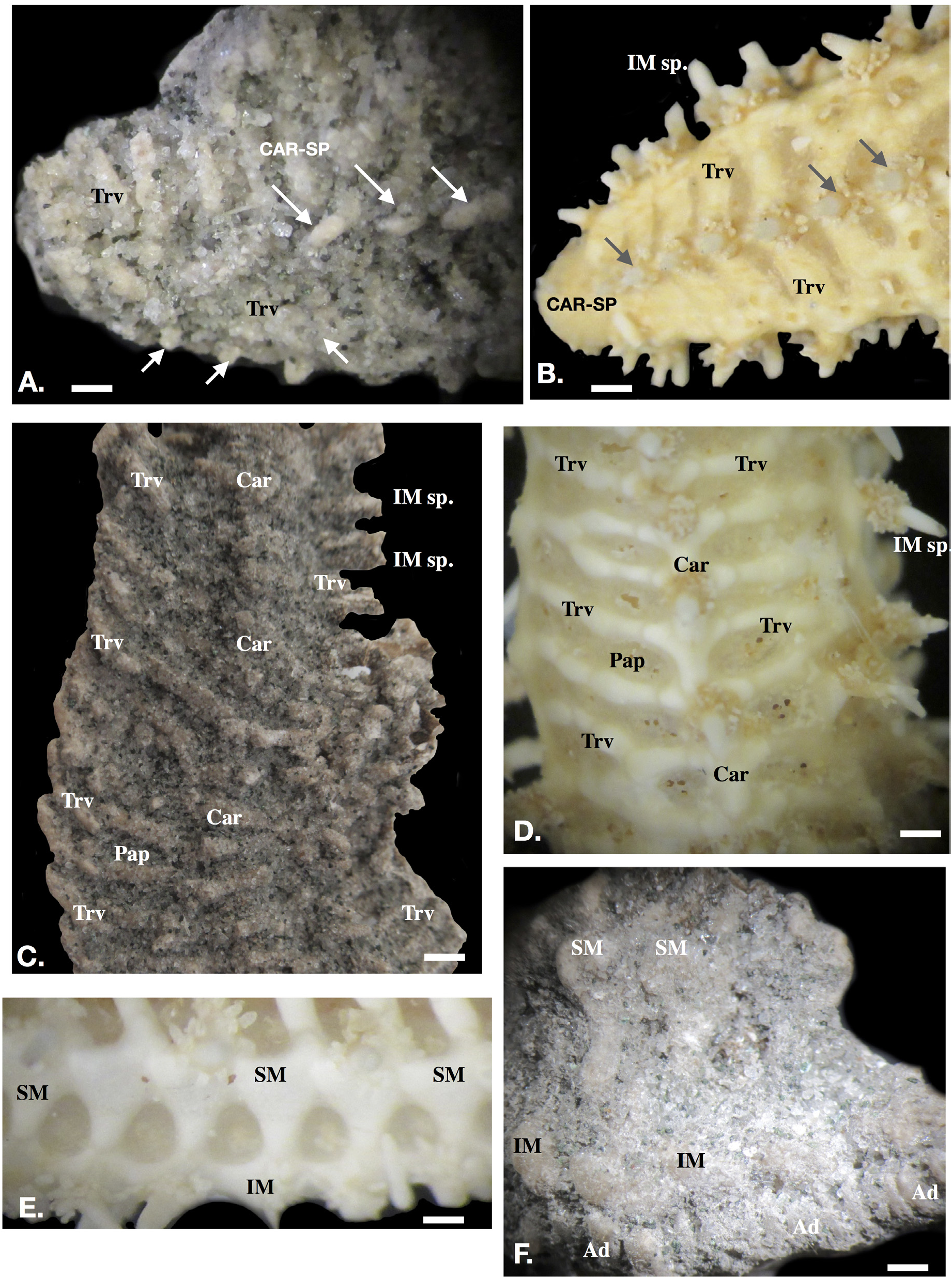

FIGURE 1A–F View FIGURE 1 , 2A–D View FIGURE 2

Description. Skeleton reticulate, forming open, broadly reticulated regions between plates ( Fig. 1A–F View FIGURE 1 ). Central carinal series present, plates with large, blunt spine as well as broken spine bases ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A-B). Transverse irregular ribs, composed of lobate plates corresponding each to a carinal plate with superomarginal and inferomarginal plates ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A-C showing fossil, B-D showing extant). Regions between transverse ribs extensive, irregularly quadrate in shape but openings formed by reticulations are regular in series along arm, becoming smallest distally adjacent to terminus ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A-D).

Superomarginals with conical, blunt-tipped spines on most plates, some spine bearing plates alternating with unspined plates. Superomarginal plates triangular, head broad, waist narrow ( Fig. 1E View FIGURE 1 showing extant; 1F showing fossil). Inferomarginal plates, round in cross-section, platform-like bearing what appears to be two pairs of spines on one fragment but only a single spine on another; inferomarginal spine count unclear. Spines blunt, tips spatulate. Other fragments show spines with only a single spines per plate ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 versus extant specimen, 2B). Approximately eight inferomarginal plates observed on two specimens showing a single blunt spine present on each.

Adambulacrals compressed, round to irregular in cross-section ( Fig. 2A–D, B View FIGURE 2 showing adambulacral plates from modern specimen).

Furrow spines blunt, cylindrical, appears to be 2, although the number per adambulacral is uncertain.

Three pairs of ambulacral plates present on the proximal edge of one arm fragment, these showing abactinal plate surface displaying compressed, narrow shape of each ambulacral plate. Ambulacrals also present in cross section ( Fig. 2D View FIGURE 2 ) on two fragments, these ossicles exposed and shown articulated with adambulacral ossicles.

No pedicellariae observed.

Remarks on Material. Arm fragments only, no disk. No indication of arm number. Details on surface obscured by coarse cemented sand grains. Surface details and fine contacts between plates obscured by sand grains. Crosssection through arm showing marginals, ambulacrals and adambulacrals ( Fig. 2D View FIGURE 2 ).

Material Examined. SNM PAL 618279 Rocky Point Member, Peedee Formation, Pender County. Approximately 8 pieces in total. 5 partial body fragments. These pieces nearly all show adambulacrals retained in series, with transverse plates in place or adjacent but with details obscured by sand grains. 3 arm pieces showing exceptional preservation. and associated matrix.Arm appears flattened with transverse ribs compressed and flattened over the marginal plates.

Comparisons within the Forcipulatacea. Other forcipulatacean groups were ruled out based on a characterbased process of elimination. Although ambulacral, and in some taxa the adambulacral ossicles, are similar, the Zoroasteridae and the Stichasteridae are characterized by linear papular rows with a much more developed skeleton which are absent from the specimens here.

Forcipulataceans in the “ Pedicellasteridae ,” a paraphyletic assemblage sensu Mah and Foltz (2011), which also show similar ambulacral and adambulacral ossicles, none show the strongly expressed carinal or inferomarginal spines described on the specimens here. The reticulate mesh on the material here also differs in pattern from other genera of pedicellasterids as outlined by Fisher (1928), including Ampheraster , Pedicellaster , Anteliaster , Hydrasterias and Tarsaster , most of which show either much more tightly arranged, serial papular spaces between the reticulate plates (e.g. Tarsaster ) or reticulate plates in irregular or differently shaped arrays (e.g. Ampheraster , Anteliaster ). Blake et al. (1996) ’s Cretaceous pedicellasterid Afraster shows abactinal plates with a much closer skeletal arrangement and smaller papular pores. The Paulasteriidae , which are similar to pedicellasterids, lack the skeletal plates observed in the specimens described ( Mah et al. 2015).

Fossil members of the Asteriidae include the Jurassic Germanasterias and Hystrixasterias , described by Blake (1990) as well as Cretasterias described by Gale and Villier (2013). The skeletons of these Mesozoic fossils show more strongly developed cruciform plates forming a much more closely arranged and nearly quadrate mesh which is similar to the extant zoroasterid Myxoderma . This differs from the more rib-like orientation of the plates with larger papular regions in the material described herein. The regular, open reticulate mesh and pronounced carinal series bearing large spines observed on the specimens described herein are shared characters with other members of the Asteriidae , specifically genera formerly within the now-paraphyletic Coscinasterinae, such as Coscinasterias , or Sclerasterias ( Fisher 1928) . Many but not all coscinasterine genera were shown to be part of the “pan-tropical” clade by Mah and Foltz (2011).

The genus Sclerasterias . Specimens possessed the compressed ambulacral column ossicles and reticulate skeleton which are distinctive for the Asteriidae ( Figs. 1A–D View FIGURE 1 ). The reticulate skeleton, carinal and, distinctive triangular superomarginal plates, superomarginal spines identify the specimens as Sclerasterias, Comparison with these genera suggested that Sclerasterias displayed the greatest morphological affinity with the fossil specimens described herein. Determination of the described specimens was difficult due to the fragmentary nature of the material as well as the material having been preserved with a covering of attached sand grains. However, the reticulate patterns were in regular series and elongate in shape, with transverse ribs extending from the carina to the inferomarginal series. This pattern is especially visible along the arm especially at the arm terminus ( Fig. 1A–B View FIGURE 1 ). The shape, size and rate at which these reticulate spaces gradually declined in size was nearly identical on both the fossil specimens and in extant specimens of all Sclerasterias which were examined, including the Pacific Sclerasterias euplecta ( Fisher 1906) and the Atlantic Sclerasterias contorta ( Perrier 1881) . Other prospective asteriid genera, such as Coscinasterias , Astrostole , and Marthasterias , while similar in appearance, lacked the same distinct serial reticulate openings which were observed on Sclerasterias , especially on the arm terminus.

Also important for identification was the presence of the triangular shaped superomarginals with the broad head and relatively narrow waist which closely resembled the superomarginal plates in living Sclerasterias , such as S. heteropaes ( Fisher 1928, Pl. 53, fig. 2)

The spatulate inferomarginal spine was consistent with those observed on living Sclerasterias ( Fig. 2A–B View FIGURE 2 ). Specimens described herein mostly showed one spine per inferomarginal plate with one plate possibly displaying two. Fisher (1928) and other accounts (e.g. Clark & Downey 1992) have outlined that Sclerasterias consistently displays two spines per inferomarginal plate. The second spine, which is generally smaller and more weakly articulated is likely absent due to poor preservation.

It is plausible that there is no second inferomarginal spine and that the single observed inferomarginal spine is the basis for a separate, extinct genus of Asteriidae , perhaps similar to Sclerasterias . However, the specimen’s fragmented nature precludes a conclusive determination and other skeletal characters, such as the shape of the superomarginal plate and the distinct repeating reticulate skeleton on the armtip suggest Sclerasterias .

Potential Phylogenetic Importance. The observed material suggests a first occurrence of the recent asteriid genus Sclerasterias from the Cretaceous of North America, which had previously been known only from the Eocene Sclerasterias zinsmeisteri from Seymour Island, Antarctica ( Blake & Aronson 1998). Modern Sclerasterias includes 15 species which are found primarily at tropical to temperate latitudes in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans at shallow to deep-sea depths (3–700 m). Modern species have not been recorded from high-latitude settings.

Within the two and three-gene molecular trees for the Forcipulatacea developed by Mah and Foltz (2011) the Asteriidae formed distinct lineages with regional partitioning. This included a Boreal clade which included coldwater and temperate genera largely from the North Pacific, a Pan Tropical clade with warm-water and temperate genera, and an Antarctic clade which included taxa primarily from the Southern Hemisphere. Within this context, Sclerasterias occupied important but variable positions. On the two-gene tree Sclerasterias was the sister branch to a clade containing the Pan Tropical and Antarctic clades, suggesting a close relationship to taxa in equatorial and southern hemisphere settings whereas on the three-gene tree Sclerasterias was supported, albeit poorly, on a clade with the Atlantic Marthasterias as a sister clade to most of the northern hemisphere Asteriidae . It was suggested by Mah and Foltz (2011) that most of the Asteriidae sensu strictu diversified in the Cenozoic relative to the more stemward Forcipulatacea (i.e. the Zoroasteridae , “pedicellasterids”, etc.).

Survey of modern Sclerasterias species suggests that it can be best described as a generalist tolerating a broad range of environments across its range. Modern Sclerasterias species occur in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans ( Clark & Mah 2001) and are present in diverse habitats ranging from shallow subtidal settings (e.g., Barker & Xu 1991) to steep rock walls on New Zealand Fjords ( Grange et al. 1980) to deep-sea cold-seeps (e.g. Gordon 2010). Barker and Xu (1991) noted that offshore individuals of Sclerasterias mollis were larger and showed higher gonad and pyloric caeca indices than inshore members, suggesting adaptation to food availability and/or population density.

It is argued that the presence of Sclerasterias in the Maastrichtian (Cretaceous) of North America would be consistent with a widely occurring generalist taxon present in the Tethys and the Pacific oceans in the Mesozoic with subsequent regional or other environmental changes could have led to differentiation of the clades within the Asteriidae .

Historical Biogeography. Five species of extant Sclerasterias are known from the Atlantic ( Clark & Downey 1992) with two species known from off the eastern coast of the United States, Sclerasteiras contorta ( Perrier 1881) , which occurs from Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to Brazil at a depth range of 384–424 m and Sclerasterias tanneri ( Verrill 1880) , which is recorded from Newfoundland to Cape Hatteras at a depth of 62– 699 m. A Cretaceous occurrence in North America would be consistent with an historical western Tethyan distribution for Sclerasterias spp. in the western Atlantic.

| SNM |

Slovak National Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |