Acinonyx jubatus (Schreber, 1775)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6376899 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6772746 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5923B274-467D-C81D-E2E8-C98DFA8F9C07 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Acinonyx jubatus |

| status |

|

Cheetah

French: Guépard / German: Gepard / Spanish: Guepardo

Taxonomy. Felis jubata Schreber, 1775 ,

Western Cape Province, South Africa.

A single-locus genetic mutation produces the blotched tabby pattern of the so-called King Cheetah, once classified as a separate species, A. rex , its distribution restricted to the more densely vegetated areas of southern Africa, centered on Zimbabwe, with an isolated record from West Africa. Described race raddei merged with venaticus. Races mngorongoroensis, oberg, raineyi, and velox included in fearonui. Five subspecies recognized.

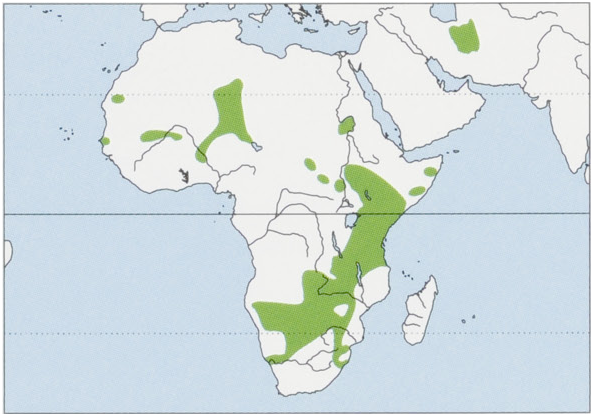

Subspecies and Distribution.

A. j. jubatus Schreber, 1775 — S Africa.

A. j. fearonii A. Smith, 1834 — E Africa.

A. j. hecki Hilzheimer, 1913 — NW Africa.

A. j. soemmeringui Fitzinger, 1855 — Somalia to Lake Tchad.

A. j. venaticus Griffith, 1821 — Iran. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 121-145 cm, tail length 63-76 cm. Mean weight 54 kg (39-59 kg) for males and 43 kg (36-48 kg) for females in Namibia. Shoulder height 79-94 cm. Males average larger than females. Cheetahs of the Sahara are smaller: two adult males had a shoulder height of only 65 cm. Tail about half the head-body length, height at the shoulder accentuated by an erectile crest of hair. Profile of back slightly concave; the hindquarters are lower than the shoulders. Eyes edged with white underneath, iris orange-yellow, pupils round. Ears small and widely set, with black and white markings behind. Head and face are rounded, with characteristic “tear lines”, heavy black lines that extend from the inner corner of each eye to the outer corner of the mouth. Coat of adults is slightly harsh with short hair. Color pale fawn to yellow, darker along the mid-back, covered all over with evenly spaced, small round black spots. Chin, throat and posterior parts of the belly are white. Distal part of the tail is spotted; the spots tend to coalesce into two to three black tail rings; tail tip is white. Front limbs spotted inside and outside, the hindfeet from the ankles to the toes devoid of spots. Top of the head and cheeks finely spotted; pattern of spots individually unique. Both melanistic and albino Cheetah specimens recorded. Remarkably pale animals with short hair, ocher spots, and muted “tear lines” and tail rings are reported from the Sahara. The “ rex ” form has longer, silkier hair with the erectile crest of neck and shoulders up to 7 cm long. Very young Cheetah have extraordinary coloring for camouflage, a mantle of smoky white long hair above, near black below. Their underparts lighten and spots emerge before two months of age, but the pale mantle disappears more slowly and traces of it are still present in animals one year old. The Cheetah is built for speed, with a deep chest, wasp-like waist, and proportionately longer limbs than cats of comparable size. Flexion of elongated spine increases stride length. Canines are small relative to other felids. The reduced roots of the upper canines allow for a larger nasal aperture for increased air intake, critical for allowing the Cheetah to recover from its sprint by “panting” while suffocating its prey for up to 20 minutes. The diastema behind the canines is very small or missing, unique in cats. Adult Cheetah have blunt claws that although retractable, remain exposed, lacking the skin sheaths found in most other felids, providing additional traction like a sprinter’s spikes. Claw marks visible in the spoor. Prominent sharp dew claws, set well up on the front foot, used as hooksto trip up fast-running prey. The digital and metacarpal pads are extremely hard and pointed at the front, an adaptation to sudden braking. Palmar pads with a pair of prominent longitudinal ridges serve as anti-skid devices. Long laterallyflattened tail provides balance as Cheetah swerves during the chase. Enlarged bronchi, lungs,liver, heart, and adrenals. The top of the skull is raised as are the large eyes.

Habitat. Distributed primarily throughout the drier parts of sub-Saharan Africa, avoiding forest and only thinly distributed in more humid woodland. Most frequently observed on open grassy plains, but may prefer a mosaic of woodland and grassland using bush, scrub, and open woodlands. May expend less energy for hunting with more cover present. Range up to 1500 m in Ethiopia and 2000 m in the mountains of southeast Algeria. Well adapted to arid conditions, surviving in small populations around central Saharan mountain ranges.

Food and Feeding. Specialized on gazelles and small to medium-sized antelopes as prey. Major prey is Thomson's and Grant's Gazelle, Gerenuk ( Litocranius wallerr), Impala, Lesser Kudu (7 Tragelaphus imberbis), and dik-dik ( Madoqua ) in East Africa; Springbok, Impala, calves of Greater Kudu, Giraffe and even African Buffalo, Southern Reedbuck, Puku ( Kobus vardonii), and Common Warthog in southern Africa; Hartebeest, Oribi (OQurebia ourebi), and Kob in Central Africa. Saharan Cheetahs occasionally take Barbary Sheep and ostrich. In the absence of ungulate prey, Cheetahs may entirely subsist on smaller prey like guineafowl and other ground-living birds and hares, the latter especially in Iran, but male coalitions also bring down large prey like Blue Wildebeest. In all studies, young prey animals are taken in preference to adults. One case of male cannibalism reported. Cheetahs often lose their kills to Lions, Leopards and hyenas. They rarely scavenge or return to a previously abandoned kill; however, may remain near large kills in the absence of more powerful predators on ranchland. The Cheetah starts eating at the hindquarters first. An individual can consume 14 kg at onesitting and a group of four finished an impala carcass in just 15 minutes. This fast swallowing helps to counter loss to competitors. Average meat consumption is 2-4 kg/day. Cheetahs hunt by sight. Prey is often detected from a vantage point. They prefer to stalk toward vigilant adult prey, walking semi-crouched, freezing in mid-stride or crouching if the quarry looks up, to within less than 50 m, before racing out at about 60 km /h. They also wait crouched if they see an unsuspecting prey moving toward them, or walk slowly toward a herd of gazelles in full view, then break into a sprint from 60-70 m away if the herd has not run off. Some rushes are started from as far as 600 m away if prey is grazing or is oblivious to Cheetah’s presence, particularly toward a standing or nursing neonate gazelle. Sprints rarely last longer than 200-300 m, maximum of 600 m. Top speed has been recorded at 102 km /h, strides are up to 9 m, and all four feet are airborne at least twice in each stride. The respiratory rate climbs from 60 to 150 breaths per minute in a high-speed chase. When drawing level with its prey, a Cheetahs knocks an antelope off balance by slapping it with a front paw on the shoulder, rump, or thigh. The dew claws help to secure the prey. The Cheetah then reaches for the throat and clamps the muzzle or windpipe shut with its jaws. Larger prey is suffocated within 2-10 minutes, then the kill is dragged into the nearest shade or cover. Hares are killed with a bite through the head. Hunting success wasslightly over 50% on adult gazelles and was 100% on small fawns in the Serengeti. Single Cheetahs killed prey every 25-60 hours in Nairobi National Park. In Kalahari Desert they travel an average of 82 km between drinks of water, mainly satisfying their moisture requirements by drinking blood or urine of their prey or eating tsamma melons.

Activity patterns. Predominantly diurnal, when competing predators like Lions and Spotted Hyenas are less active. Cheetahs spend most of the day resting, with hunting peaks between 07:00 and 10:00 h and between 16:00 and 19:00 h. Cheetahs of the Saharan mountains, in the absence of larger predators, often hunt at night when temperatures are cooler. Territories and preferred routes are marked with sprays of urine, feces, and occasionally by claw raking. Markings are frequently made near regularly used observation points like termitaries, rocks, or leaning trees, so-called “play trees”, or at path junctions. Cheetahs purr when greeting known individuals; the striking contact call is an explosive yelp that can carry for 2 km. Juveniles make a “whirr”, or fast growl, which may rise to a squeal or subside to a rasp during fights over a kill. Bird-like chirps, hums, purrs, and yelps are unique to this species, which can be very vocalin its rare social encounters.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. A greater degree of sociality has been observed among Cheetahs than for most felids, with the exception of the Lion. Male and female littermates tend to stay together for about six months after independence, when female young split off upon reaching sexual maturity. Male littermates remain together in coalitions and sometimes defend territories. Male coalitions in the Serengeti, in particular trios, may include unrelated males. Males in coalitions are more likely than solitary males to gain and maintain territories; they are in better condition and have better access to females during periods of gazelle concentration. Nonterritorial males, representing 40% of the Serengeti male population, live a nomadic existence and wander widely. Groups of up to 14-19 animals occasionally reported where other large predators have been eradicated. On some occasions groups of adults with cubs have been reported. Groups of mixed sex have been seen hunting together, probably reflecting mating activity and a large litterjust before independence. Solitary Serengeti males and female adults are semi-nomadic, with large, overlapping home ranges 800-1500 km? male coalitions defend territories of 12-36 km?, but up to 150 km?. Mortality of adult male Cheetah is as high as 50% as a result of competition for territories. Territories are centered around areas with periodically high Thomson's Gazelle numbers, attracting females to their favorite prey. In Kruger National Park, South Africa, where prey species are non-migratory, both males and females occupy small home ranges of similar size, on average 175 km.

Breeding. Largely aseasonal with birth peaks during the rainy season (November— May) in Serengeti. Cheetahs have a long, drawn out, and complex courtship. Females are polyestrous, cycling approximately every twelve days (range 3-27). Length of estrus varies from 1-3 days, being shorter when mating occurs; there are some reports of females being receptive for 10-14 days. Cheetahs are induced ovulators. Mating lasts a minute or more and can be followed by gaps of eight hours before the next episode. Gestation lasts 92 days (range 90-98). Littersize averages four (range 1-8), larger than in most other felids, with larger litters in Namibian rangeland in absence of larger predators. Interbirth interval 15-19 months, but females readily go into estrus and conceive after losing a litter. Large litter size may be a strategy to offset high juvenile mortality caused by predators. Birth weight is 250-300 g. Sex ratio is 1 male: 0-95 female. The blind, helpless cubs are born in a lair of long grass, thickets, or in a temporary “borrowed” burrow and remain hidden for approximately eight weeks. They open their eyes at 4-14 days and are frequently carried to a fresh hiding place by the mother. At 3-6 weeks a set of milk teeth erupts, replaced by adult teeth at about eight months. Cheetah cubs can retract their claws for up to ten weeks of age, and they are able tree climbers. Nursing terminates at about four months. The cubs accompany their mothers on hunts from eight weeks onward and are introduced to solid food. They are very playful during the first six months, starting to practice hunting afterwards, but are still not adept when leaving their mothers. Mothers sometimes bring back live prey for the cubs to practice their skills. Cub mortality up to the age of three monthsis very high. Cubs are killed by other large carnivores and even baboons ( Papio sp.). In Nairobi National Park, cub mortality is as low as 43%. In the Serengeti, with high Lion density, 95% of 125 cubs failed to survive to independence; 73% of the cub deaths were due to predation. Cubs become independent at 18 months (range 13-20 months), while females leave their sibling groups with 17-27 months. Sex ratio of subadults and adults changes to 1 male: 1-9 females, suggesting differential male dispersal and mortality. Wild female Cheetah reproduce at 2-3 years for the first time, and males reproduce at 2-5-3 years. In captivity males are normally fertile at 1-2 years, females at 2-3 years. Females remain fertile up to ten years, males up to 14 years. Longevity in the wild is up to 14 years; however, the female average in the Serengetiis seven years. Territorial males may live longer than single males. Captive Cheetahs live on average 10-5 and up to 21 years. Difficult to breed in captivity, with females conceiving infrequently, but social setting may not be adequate. High levels of sperm abnormalities (71-76%) in both wild and captive Cheetahs, but no evidence that reproduction is compromised in the wild. Cheetahs were kept by nobility and trained to hunt dating back 5000 years to the Sumerians. 3000 Cheetahs were kept during the lifetime of one Moghul emperor. By the early 1900s Indian Cheetahs were so scarce that African animals were imported to sustain the stables, as there was no success breeding them.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I, quota system for live animals and trophies in some southern African countries. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List, with subspecies venaticus and hecki classified as Critically Endangered. Population estimate for sub-Saharan Africa was 15,000 in the 1970s, 9000-12,000 in the 1990s. Two largest meta-populations occur in East Africa ( Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia) and southern Africa ( Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia). Cheetahs are very rare in Sahel and semi-arid zone of West Africa, much of it having been degraded by humans through hunting of prey animals and livestock overgrazing. Extinct from 20 countries. Possibly present in low numbers in isolated Qattara Depression in N Egypt. Subspecies venaticus has largely been exterminated from Near East and Asia, with possibly fewer than 50 individuals surviving in north-central Iran. About 95% of present Namibian population of 2000-3000 occurs on privately owned land; number of Cheetah believed to have declined by half in Namibia since 1980. Cheetah densities may range from a high density of one adult per 6 km? following concentrations of migratory gazelle, to low density areas of one adult per 191 km ®. Cheetahs exist in higher densities in pastoral areas outside of protected areas than inside them. On Namibian ranchland, the species’ stronghold, average is one adult per 50 km *. Genetic research demonstrated a very high level of homogeneity in coding DNA, suggesting a series of population bottlenecks in its history, the first and most significant occurring 10,000 years ago. Lack of genetic diversity may render the Cheetah exceptionally vulnerable to changing environmental conditions and disease. In captivity, epidemics of infectious disease have occurred, with high mortality. No epidemics reported from the wild, although high incidence of mange in some parks. Strategy of relying solely upon the limited system of protected areas within the Cheetah’s range may not be sufficient to ensure conservation, due to the impact of other predators, which kill offspring and drive Cheetahs off their kills. Outside protected areas in Namibia, there are conflicts with people over predation on livestock: annual losses of 10-15% for sheep and goats and 3-5% for cattle calves are reported. Stock losses are especially severe where natural prey base has been eliminated or reduced. Cheetahs are not especially susceptible to taking poisoned bait, but their numbers in Namibia have been reduced through shooting and trapping at “play trees”. Permitting trophy hunting in southern Africa has the goal of encouraging landowners to accept and profit from Cheetahs on their lands. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) work to educate farmers about appropriate management steps to minimize stock losses, such as using fencing, guard dogs, and donkeys, to aid in the conservation of the wild prey base and to protect its habitat.

Bibliography. Bertram (1979), Bosman & Hall-Martin (1997), Bothma (1998), Bottriel (1987), Broomhall et al. (2003), Caro (1982, 1994), Caro & Collins (1986, 1987a, 1987b), Caro & Laurenson (1994), Caro, Fitzgibbon & Holt (1989), Caro, Holt et al. (1987), Divyabhanusinh (1995), Dragesco-Joffé (1993), Durant (1998), Eaton (1970a, 1970b, 1974), Ewer (1973), Fitzgibbon & Fanshawe (1989), Floria & Spinelli (1967), Frame (1975-1976, 1980, 1992), Frame & Frame (1981), Gros (1990, 2002), Hills & Smithers (1980), Hunter & Skinner (1995), Kingdon (1971-1982), Kruuk & Turner (1967), Labuschagne (1979, 1981), Laurenson (1995), Laurenson et al. (1992), Lindburg (1989), Marker-Kraus (1992), Marker-Kraus & Grisham (1993), Marker-Kraus & Kraus (1991), McKeown (1992), Mills (1990), Mills & Biggs (1993), Mitchell et al. (1965), Morsbach (1987), Nowell & Jackson (1996), O'Brien (1994), O'Brien et al. (1983), Philips (1993), Pienaar (1969), Pocock (1916e, 1927), Ruggiero (1991), Schaller (1968, 1972), Sharp (1997), Skinner & Smithers (1990), Smithers (1971), Stander (1990), Stuart & Stuart (1996), Sunquist & Sunquist (2002), Van Aarde & Van Dyk (1986), Van Dyk (1991), Van Valkenburgh (1996), Wildt et al. (1987), Yalden etal. (1980).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.