Caracal caracal (Schreber, 1776)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6376899 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6772718 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5923B274-4670-C812-E7B5-C4F1F6759EF9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Caracal caracal |

| status |

|

Caracal

French: Caracal / German: Karacal / Spanish: Caracal

Other common names: Red Lynx, Caracal Lynx

Taxonomy. Felis caracal Schreber, 1776 View in CoL ,

Table Mountain, near Cape Town, South Africa.

Caracal were originally thought to be allied with Lynx lynx , L. canadensis , L. pardinus , and L. rufus . However, recent genetic analyses show that the caracal is not part of the lynx group but rather is more closely allied with Profelis aurata . The two species are thought to have shared a common ancestor 4-85 million years ago. Nine subspecies recognized.

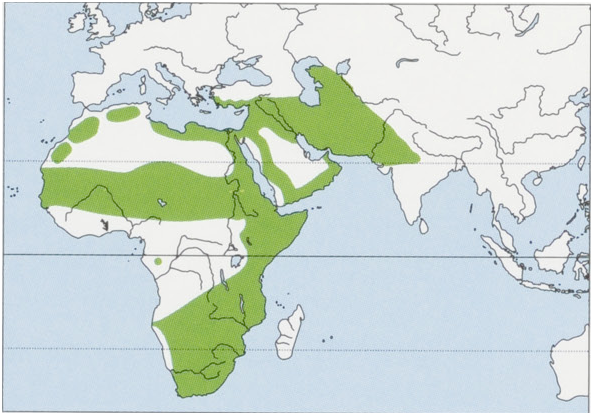

Subspecies and Distribution.

C. c. caracal Schreber, 1776 — E & S Africa.

C.c.algira Wagner, 1841 — N Africa.

C.c. damarensis Roberts, 1926 — Namibia.

C.c. limpopoensis Roberts, 1926 — N Transvaal.

C.c. lucani Rochebrune, 1885 — grasslands of SE Gabon.

C. c. michaelis Heptner, 1945 — deserts of Caspian Sea region, E to Amu Darya River.

C. c. nubica Fischer, 1829 — Cameroon E and N to Nubian Desert.

C. c. poecilotis Thomas & Hinton, 1921 — W Africa.

C. c. schmitzi Matschie, 1912 — Turkey, Palestine E to India. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 61-105. 7 cm,tail 19.5-34 cm. Adult males heavier (8-20 kg) than adult females (6.2-15. 9 kg). Caracals are slender, long-legged, medium-sized cats. Hindlegs are powerfully built and longer than the front legs, giving the cat the appearance of being taller at the rump than at the shoulder. The short tail extends only to the animal’s hocks. Fur is short and unspotted. Coat color on back and sides varies from a uniform tawny gray to brick red. Belly, chin, and throat are whitish and marked with pale spots or blotches. Melanistic individuals have been recorded. The large, conspicuous ears are black on the back and adorned with black tufts that may be 4-5 cm long. The skull is high and rounded and the jaw is short and heavily built, with large powerful teeth. Facial markings include a dark line running from the center of the forehead to near the nose and white patches above and below the eyes and on either side of the nose.

Habitat. Caracal are found in dry woodlands, savanna, acacia scrub, hilly steppe, and arid mountain areas to 2500 m. They do notlive in true desert or dense tropical rainforest. They are often associated with edge habitats where forest and grassland meet, and though they use open grasslands at night, they require access to bushes and rocks for daytime restsites.

Food and Feeding. Caracal generally take prey that weigh less than 5 kg, including hares, hyrax, small rodents, and birds. They will, however, take larger (over 15 kg) prey if the opportunity arises. In two studies in South Africa’s Mountain Zebra National Park, hyrax were found in 53 and 60% ofscats, and Mountain Reedbuck were found in eleven and 20% of scats, respectively. Due to their greatersize, reedbuck contributed 62 and 72% of meat consumed. Caracal also killed a variety of other bovids in and outside the park, including Springbok, duiker, and Steenbok. Bovids, including Reedbuck, Common Duiker (Silvicapra grimmia) and Blue Duiker (Philatomba monticola), Steenbok, Bushbuck, Common Rhebok ( Pelea capreolus), and Klipspringers ( Oreotragus oreotragus) were the most frequently occurring (43-6%) prey items in the stomach contents of Caracal from the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Hyrax and Scrub Hare combined ranked second at almost 20%. In Botswana, Caracal fed mainly on small mammals but they also ate hares, spring hares, quail, partridge, and lizards. Mammals were also the dominant prey of caracal in Israel, and hares were the principal prey. Birds, mainly partridges, made up 24% of the cat’s diet in this area. Incidental prey included mole rats, hedgehogs, the Egyptian Mongoose, and reptiles and insects. In Turkmenistan, small prey such as hare, sand rats, jerboas, and ground squirrels dominate the Caracal’s diet. Caracal stalk as close as possible to their prey before making a final sprint; they also use their powerful hindlegs to make prodigious leapsinto the air to capture birds. Hare-sized prey is killed with a bite to the nape. Larger prey is usually killed by suffocation with a throat bite.

Activity patterns. The Caracal is predominantly nocturnal. One study in Israel found the cats were most active from dusk to dawn, although they sometimes extended their activity into the early morning. Differences in the duration of daytime activity were largely dependent on daytime temperatures and the activity patterns of their prey, which are also affected by ambient temperatures. Caracals in the Sahara are crepuscular and nocturnal, but only in the hot season. At cooler times of the year or on overcast days during the rainy season the cat may be active until mid-morning or become active by midto late afternoon. In more hilly terrain, where there is abundant escape cover, Caracals have a tendency to become bold and move around in the daytime.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In Israel, radio-collared males traveled an average of 10-4 km per day; females traveled an average of 6-6 km. Home ranges of five adult males in Israel were large, averaging 220 km? compared to an average of 57 km? for four adult females. Female home ranges were greatly reduced when they had small young but gradually expanded as the young became mobile. Each male’s range overlapped the smaller ranges of one or more females and there was considerable overlap (50%) between adjacent male ranges. Female ranges showed much less overlap (25%). In the western sector of Cape Province, South Africa, the home range size of four adult females averaged 18-2 km?* while an adult male’s home range measured 65 km ®. In Mountain Zebra National Park the home ranges of males and females residing inside the park averaged 15-2 and 5-5 km? respectively. The home ranges of males living in the farmlands outside the park averaged 19-1 km? Caracals are solitary and most sightings are of single adults. Observations of two to four animals together most likely represent mating pairs or females with their large young.

Breeding. Caracal are polyestrous and in South Africa births have been recorded in every month of the year, with a peak from October to February. Anecdotal observations from the wild suggest estruslasts from 3-6 days and mating pairs moved together for about four days. In Israel, Caracals were found to have a rather unusual mating system in which a female copulated with several different males in succession. The mating order appeared to be determined by age and weight of the male. After a gestation period of 68-81 days the female typically gives birth to two kittens. Litter size ranges from 1-6. Young are born in caves, tree cavities, or burrows and weigh 198-250 g at birth. Permanent canine teeth erupt at 4-5 months and by ten months the young have a complete set of permanent teeth, which coincides with the timing of dispersal. Subadults leave their natal ranges when they are 9-10 months old. Males and females are sexually mature by 12-15 months of age.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I (Asian population); otherwise CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Not protected by national legislation over most ofits geographic range. The Caracal is rare in North Africa, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, and Arabia, and on the verge of extinction in India. It is common in Israel and over much ofthe southern African portion ofits range. Caracal is in the unique position of being classified as endangered in the Asian portion of their range and hunted as a problem animal in southern Africa. In parts of Namibia and South Africa, domestic livestock make up a significant portion (17-55%) of the Caracal’s diet and large numbers of Caracal are destroyed annually by farmers. However, Caracal typically recolonizes these heavily hunted areas. Habitat loss is one of the main threats to the species in the eastern portion ofits range and the Caracal has suffered heavy losses from fur trappers in India. However, Caracal pelts have a low value on the international market and the world fur trade does not pose a threat to the species.

Bibliography. Bernard & Stuart (1987), Dragesco-Joffé (1993), Grobler (1981, 1982), Johnson & O’Brien (1997), Mendelssohn (1989), Mukherjee et al. (2004), Norton & Lawson (1985), Nowell & Jackson (1996), Pringle & Pringle (1979), Rosevear (1974), Smithers (1983), Stuart (1981, 1984, 1986), Stuart & Hickman (1991), Stuart & Stuart (1985), Sunquist & Sunquist (2002), Visser (1976a), Weisbein & Mendelssohn (1990), Werdelin (1981).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.