Felis nigripes, Burchell, 1824

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6376899 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6772762 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5923B274-4647-C82B-E2E2-C269FAB693D9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Felis nigripes |

| status |

|

Black-footed Cat

French: Chat a pieds noirs / German: SchwarzfulRkatze / Spanish: Gato de pies negros

Other common names: Small Spotted Cat, Anthill Tiger

Taxonomy. Felis nigripes Burchell, 1824 View in CoL ,

Kuruman, South Africa.

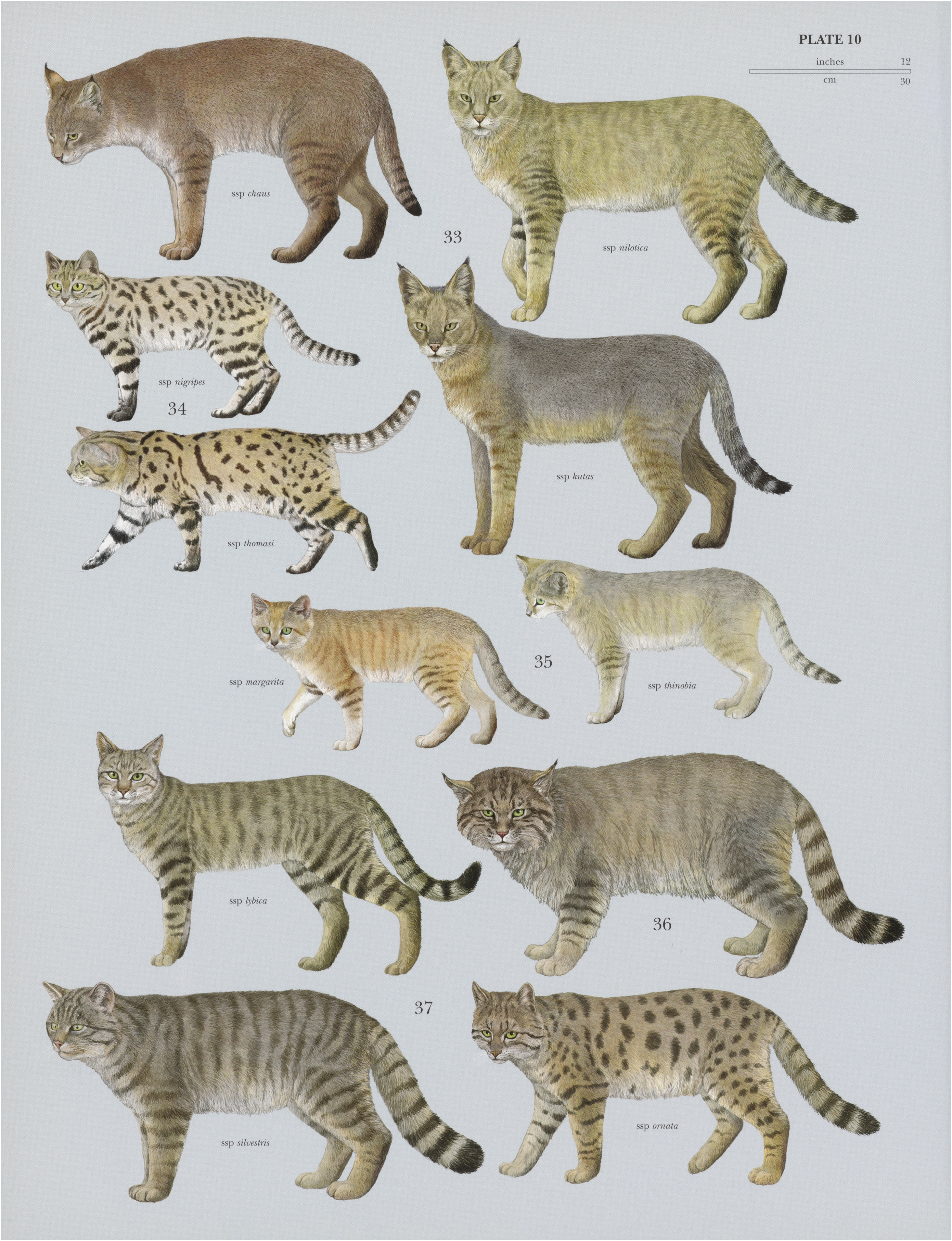

Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

F. n. nigripes Burchell, 1824 — Namibia through the Kalahari to NE South Africa.

F. n. thomasi Shortridge, 1931 — S South Africa (Eastern Cape Province). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 36-52 cm, tail 126-20 cm; weight 1.2-45 kg, adult males distinctively larger than adult females. The smallest cat in Africa. Small stocky cat with broad head and large, widely spaced, rounded ears. The nose is very small and varies from red to black in color. Eyes are dark yellow to light greenish. The soft fur grows longer and denser during winter. The margins of the eyes, ears and mouth are white. There are two black cheek stripes running from the corner of the eyes and from below the eyes to the edge of the face. On the back of the neck there are four black bands, two running along the back and onto the shoulder. The body color varies from cinnamon buff to tawny or off-white. There are bold black or rust-tinged bands or rings on the shoulders and high on the legs, up to five on the hindlegs and two on the front, and distinct spots of the same color on the body. The throat has two or three black to reddish stripes that are either solid or broken up. The underparts are pale buff or white. The tailis short (less than 40% of head-body length) and narrowly black-tipped; the backs of the ears are the same color as the body. The hair on the undersides of the front paws and back legs is black. The skull is high and rounded. The auditory bullae are exceptionally large, their total length being 25% of the total skull length and their width, at the widest point 18%. Races not well defined, possibly representing a geographical cline from the smaller, paler nominate, with more bleached ground color and less distinctive brown striping, to the larger, more vividly colored thomas: with jet black bands and spots.

Habitat. Inhabits dry, open savanna, grasslands, and Karoo semi-desert (savanna biome) with sparse shrub and tree cover with a mean annual rainfall of between 100-500 mm annually; absent from the driest and sandiest parts of the Namib and Kalahari Deserts. Seems to avoid rocky terrain and bushy country. Presence of South African Spring Hare burrows and Trinervitermes termitaria for shelter may be crucial since 98% of 184 resting places in central South Africa were in abandoned South African Spring Hare burrows. In some areas frequently uses hollowed out termitaria; hence the common name “anthill-tiger.” Also rests under rock slabs.

Food and Feeding. Opportunistic carnivore, taking everything it can overpower. Of seven stomachs collected in Botswana four contained murid rodents, three spiders, and one each elephant shrews, reptiles, insects, and birds. In central South Africa 43 vertebrate prey species identified. 14 mammal species comprised 72% of the total prey mass consumed. Most important, with 39% of prey mass, were murids; 21 species of birds (26%), mainly larks, with eggs of various species taken; eight species of frogs and reptiles ( Gekkonidae , Scincidae , Colubridae ); prey up to the size of hares, mongooses and pigeons, sandgrouse, and bustards taken. A minimum of ten invertebrate species were eaten, some as small as the alates of harvester termites. Average preysize is 24 g. In central South Africa on average males kill larger prey; the smaller and more agile females are more successful in catching small birds. In summer both sexes concentrate on abundant small rodents. In winter a higher proportion of larger (over 100 g) birds and mammals are taken. Three different hunting styles identified: “fast-hunt” when moves in swift bounds at 1-2 km/h trying to flush prey from cover; “slow-hunt” involving a slow stalk at an average speed of 0-5—-0-8 km/h, while looking and listening carefully; and “sit-down”, waiting at a rodent den system for up to two hours. About 70% of the night is spent moving. Birds are sometimes snatched from the air. Hunting success very high, about one vertebrate prey animal caught every 50 minutes and 10-14 rodents or small birds caught per night, representing 200-300 g of food or about 20% of the body weight; record intakes can reach 450 g per night. Excess food is cached and scavenged readily. Independent of water but will drink occasionally when wateris available.

Activity patterns. Nocturnal and crepuscular; when moving during daylight birds mob them. Hunting occurs throughout the night in all weather conditions and temperatures. Are occasionally shadowed by Marsh Owls, which catch flushed prey animals. Small body size allows the cat to hunt and rest in open arid areas. Its auditory bullae are exceptionally well-developed, enhancing hearing ability in areas with little vegetation cover. Considered to be the southern representative of the Sand Cat, which has similar proportions. Sight is acute for crepuscular and nocturnal hunting.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Nightly travel distance is between 4-5 and 16 km (mean = 8 km). Males have larger cumulative home ranges (17-6 km?) than females (9-5 km?) and their ranges overlap those of 1-4 females. Intra-sexual overlap is marginal. Home range size is likely to vary between regions according to local resource availability. Solitary, except during mating; the only other prolonged social contact are females with dependent kittens. Communicate mainly through urine spray marking; frequency of female spraying fluctuates strongly during the year, depending on the stage of reproductive cycle, with high frequency before mating, low when pregnant, and no spraying when rearing kittens. Males spray intensively prior to mating, up to 585 sprays per night. Scent rubbing and possibly claw-raking may have signalling function. Feces are rarely covered or deposited on middens. Vocal communication, a loud meowing sound, repeated up to ten times in quick succession, mostly from males looking for females during mating season. Females rarely call in estrus. Soft calls used by males courting females and by females calling kittens. Females give special alarm call, with ears depressed, to kittens. The adult sex ratio in the wild was four males to six females. Birth sex ratio is 1-16: 1 in captivity. Captive individuals may live up to 16 years; however data from the wild indicate 4-6 years as the average.

Breeding. Females have an estrous cycle of 54 days. Mate often, 6-10 copulations during 36hour female estrous period; resident male guards females and chases and fights with intruding males. Gestation is 63-68 days; up to two litters in the spring and summer season, coinciding with the rains and high availability of food. No litters in winter. Litter size 1-4, but usually two. Birth weight 60-90 g. Kittens born in hollow termite mound (“ant hill”), or South African Spring Hare burrow; mother leaves kittens for two hours on night of birth and resumes her nocturnal hunting schedule after four days, returning infrequently to suckle kittens. Kittens moved frequently after the first week; they develop rapidly, opening eyes at 3-9 days, first take solid food at 30 days, weaned within two months. Female carries prey items to them for feeding and teaching kittens to hunt live prey. Kittens independent after 3-4 months, but remain within mother’s range for extended periods. Sexual maturity (in captivity) is seven months for females and nine months for males.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The [UCN Red List. South African red data book: rare; very inconspicuous,shy, difficult to census; 8 adults/ 60 km? in central South Africa; in low quality habitat densities probably lower; species may be expanding in some areas; threats include expansion of human settlement and arable agriculture, use of poison, desertification, and overgrazing with bush encroachment. May be susceptible to locust poisoning. Farmers setting “coyote-getters” and poisoning carcasses during control operations targeting other predators may affect since they readily scavenge. Night calling and shooting aimed at Black-backed Jackal also impacts this species in the central Karoo. Cats also fall victim to dogs, used to chase or dig outjackals during problem animal operations. Young or sick individuals and kittens are vulnerable to Black-backed Jackal and Caracal predation. Kittens and possibly adults may fall victim to large nocturnal raptors such as eagle-owls (Bubo africanus, B. capensis, B. lacteus); both wild and captive individuals often die of kidney failure (amyloidosis), indicated by high urea concentrations in the blood.

Bibliography. Burchell (1824), Leyhausen & Tonkin (1966), Mellen (1989), Molteno et al. (1998), Nowell & Jackson (1996), Olbricht & Sliwa (1995, 1997), Power (2000), Roberts (1926), Shortridge (1931, 1934), Skinner & Smithers (1990), Sliwa (1994a, 1994b, 1994c, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2004, 2006), Sliwa & Schurer (2000), Smithers (1971, 1986), Stuart (1981, 1982), Stuart & Wilson (1988), Sunquist & Sunquist (2002), Visser (1977).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.