Cebus cuscinus (Thomas, 1901)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628259 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B734-2845-0804-F43B3EE8F844 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Cebus cuscinus |

| status |

|

Shock-headed Capuchin

French: Sapajou ébouriffé / German: Peru-Kapuzineraffe / Spanish: Capuchino palido

Taxonomy. Cebus flavescens cuscinus Thomas, 1901 View in CoL ,

Callanga, Rio Pinipini, upper Rio Madre de Dios, Cuzco, Peru.

This species is monotypic.

Distribution. Poorly known, but it is believed to extend from the S (right) bank of the upper reaches of the Rio Purus in SE Peru, W into the Rio Urubamba Valley in the Cuzco Department, including the upper Rio Madre de Dios, S and E as far the Tambopata Basin, and extending into NW Bolivia. View Figure

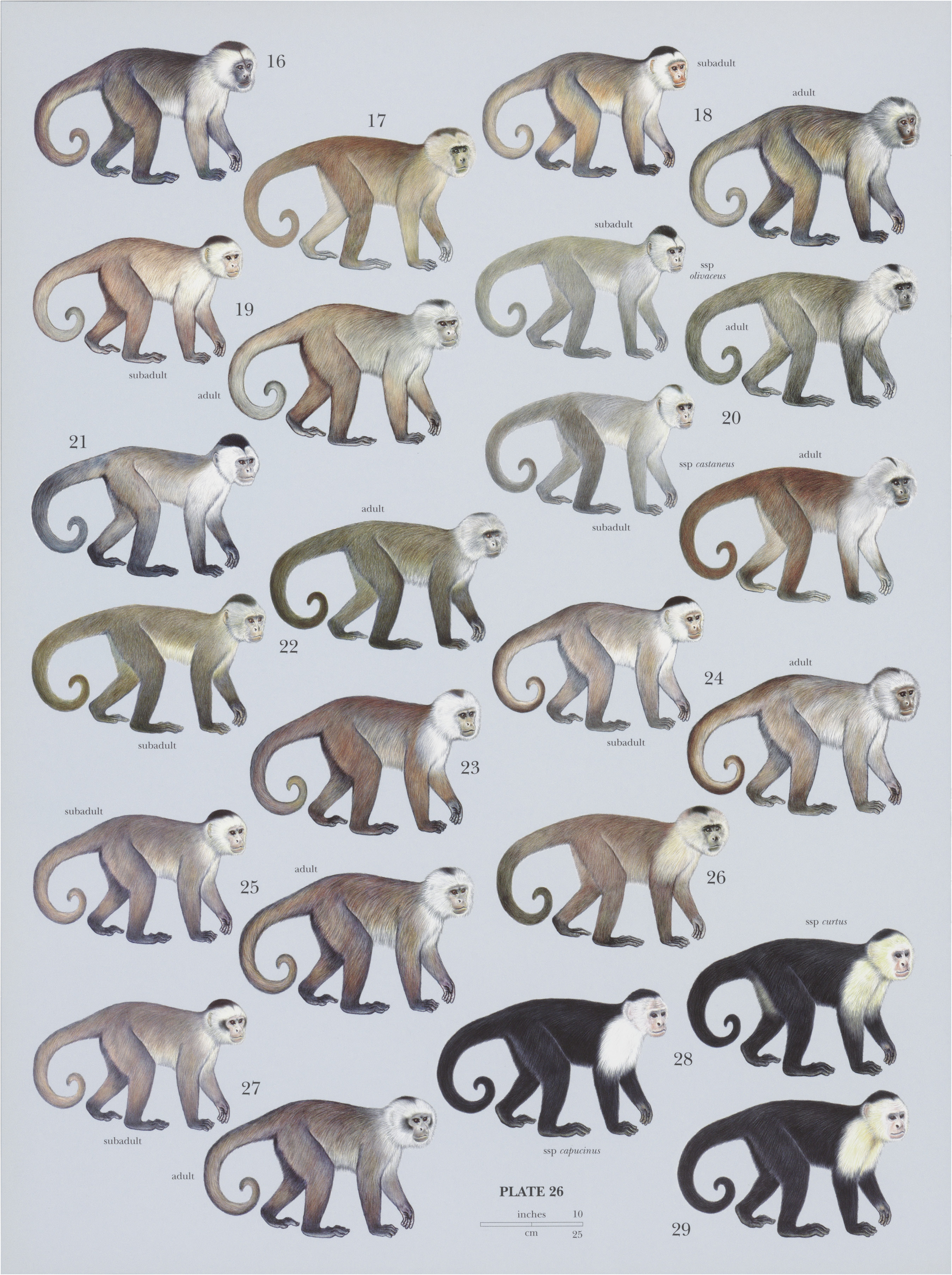

Descriptive notes. Head-body 40 cm (males) and 39-46 cm (females), tail 44 cm (males) and 39-47.5 cm (females); weight 2.8-3 kg. The Shock-headed Capuchin is similar to Spix’s White-fronted Capuchin ( C. unicolor ), but it has longer, silkier fur and is less brightly colored. Limbs are browner and contrast less with the back. The cap is large, distinct, and dark brown, and upper surface of the body is tawny-ocherous in the anterior parts and tawny toward the lower back. Lateral fringe and outer sides of upper arms are brown. The forearms are orangey-rufous on the outside, with wrists and hands darker. Outer thighs are like the rump, and shanks laterally are mixed orange-rufous. Surfaces of feet are brown to auburn. Underparts are ocherous-orange and silvery, becoming warm buff on the chest. There are whitish areas on the fronts of the shoulders and inner sides of the upper arms. The tail is cinnamon brown above, and brown below (a little paler toward the tip). The male has a broad pale frontal region sharply defining the dark brown cap, whereas the female has a dark brown frontal diadem continuous with the cap.

Habitat. [Lowland terra firma and seasonally inundated forests in the upper Amazon Basin, to the western slopes of the Andes in montane forest at elevations up to 1800 m. Shock-headed Capuchins usually occupy the middle to upper canopy but sometimes forage on the ground.

Food and Feeding. Shock-headed Capuchins in the Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Peru, have feeding habits and diet similar to the Large-headed Capuchin ( Sapajus macrocephalus ), but with some subtle and important differences in feeding strategies that allow sympatry, particularly during fruit shortages. Fruit and insects are the principal components the diet of Shock-headed Capuchins. Fruit comprises 99% of the plant part of the diet in the wet season (supplemented with pith and meristems) and 53% in the dry season. Seeds, particularly from palms, are also an important component of the diet in the dry season, and small quantities of pith, meristems, and petioles are eaten. Unlike Large-headed Capuchins, Shock-headed Capuchins can not break open Astrocaryum palm nuts to eat the endosperm—useful in the dry season when fruit is scarce. In the dry season, Shock-headed Capuchins spend hours searching through fallen bunches of palm fruits looking for those that have been attacked by bruchid beetles (subsequentto falling to the ground) but that still contain some endosperm. They smell and shake the nuts to gauge whether they still contain sufficient endosperm to make opening them worthwhile. Those they deem worthy are taken into a tree to bang them against a branch, or two nuts against each other, to open them and scrape out the hardened albumen with their teeth and fingernails. This is a prolonged process, and they spend longer time (sometimes more than two hours in a day), for less reward, than Large-headed Capuchins that spend c.45 minutes a day breaking open intact fruits from trees. To complement their dry-season diet, groups of Shock-headed Capuchins travel through much larger home ranges (more than 150 ha) than Largeheaded Capuchins to find other and large fruits crops, particularly those from widely scattered fig trees ( Ficus , Moraceae ). In the early dry season, Shock-headed Capuchins spend 56% of their feeding time on palm fruits and 41% of their feeding time on figs. Sympatric Large-headed Capuchins, in contrast, spend 64% their feeding time on palms and only 9% on figs. Shock-headed Capuchins are less destructive while foraging for animal prey and spend more time searching in litter, leaves, and tangles of lianas and much less time in palms than is typical of Large-headed Capuchins. The composition of the animal part of the diet is otherwise very similar between the two capuchins; both concentrate heavily on Hymenoptera, Orthoptera, and Lepidoptera.

Breeding. Female Shock-headed Capuchins solicit males intermittently when they are receptive, and although there is a distinct hierarchy, mating is not restricted to the most dominant male. Males take an active interest in the sexual condition of females, often sniffing their urine, evidently to see if they are in a periovulatory stage and receptive. They try to mount females even when they are not receptive.

Activity patterns. The annual activity budget of Shock-headed Capuchins in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve is foraging and feeding on insects 39%, feeding on plant material 22%, traveling 21%, resting 12%, and 6% in miscellaneous activities (e.g. grooming, play, and territorial behavior), with little seasonal change. In the early dry season, time spent eating fruits tends to be longer because of the long time they spend working on Astrocaryum nuts. They spend more time eating fruit in the morning, and foraging for animal prey increases gradually during the day and especially after resting at ¢.11:00 h. They also tend to eat fruit late in the afternoon before retiring.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Groups of Shock-headed Capuchins are multimale-multifemale and average c.15 individuals. The sex ratio is about even (1:1). They use large home ranges of more than 150 ha, spending time in any areas with fruit trees until their fruits are depleted. They may travel 1500-2200 m/day. Their ranging is nomadic, and there is no evidence of the use of a core area. Although home ranges of different groups overlap, Shock-headed Capuchins are quite territorial. Usually they move away in different directions when they perceive another group’s presence up to 100 m away. When encounters do happen, there is considerable cooperation among group members. They vocalize loudly, and dominant males come together and all group members confront the opposing group with aggressive displays and sometimes chases. This is not typical of Sapajus or Saimiri , which are considerably more tolerant of other groups. Because of relatively large home ranges of Shock-headed Capuchins, groups have access to many more fruiting trees of any particular species over a wider area of forest than is the case for sympatric Sapajus that has home ranges about one-third the size (¢.80 ha). Therefore, the diversity of the diets of Shock-headed Capuchinsis lower, but an important aspect of their wider ranging is that they are able to exploit larger fruit crops in large-canopied trees (e.g. figs) more than Large-headed Capuchins, which use smaller-canopied trees (e.g. palms). About 40% offruit feeding by Shock-headed Capuchins is in trees with crown diameters of 20-50 m compared to 12% by the Largeheaded Capuchins. The Shock-headed Capuchin lives in larger groups than Sapajus , multimale rather than single-male, and the males are philopatric and form coalitions to defend their groups. Aggressive interactions between males are less frequent than in Sapajus and males associate together more than do the females or any other age class. Males are more aggressive to females, and females are more aggressive to each other. Although an adult Sapajus male is more robust and stronger than a male Cebus , two Cebus males are able to challenge and displace a tufted capuchin male from a food source. Cebus groups are dominant as such to Sapajus groups by outnumbering them. Shockheaded capuchins often travel with squirrel monkeys ( Saimiri boliviensis ) and the groups often intermingle. Individuals can feed close together and only occasional antagonistic interactions and displacements occur (mostly in smaller-crowned fruiting trees). In the late afternoon, the two groups separate to different sleeping sites but rejoin in the morning. Squirrel monkeys generally travel in front of the Cebus groups. Predators of Shock-headed Capuchins include the larger raptors (Harpia, Morphnus, Spizaetus, and Spizastur), felids, the Tayra (Eira barbara), and snakes. Whereas a dominant male Sapajus is vigilant for aerial predators on behalf of his group (barking a warning), the dominant male Cebus hideslike any other group member. Adult males, however, do mob ground predators, giving silent threat displays.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List (as C. albifrons cuscinus ). Distribution of the Shock-headed Capuchin is not really known, and recent phylogenetic studies of the genus Cebus have highlighted the dearth of information regarding distributions of what may prove to be a number of distinct species in the southern Amazon Basin. The supposed distribution of the Shock-headed Capuchin in northern Bolivia, south-eastern Peru, and possibly the far south-western Brazilian Amazon Basin (Acre State) is relatively small, and development and colonization in some areas have resulted in considerable forest loss and hunting. Its hypothetical distribution includes some major protected areas such as Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve in Peru and Madidi National Park and Manuripi-Heath National Reserve in Bolivia.

Bibliography. Aquino & Encarnacion (1994b), Freese & Oppenheimer (1981), Hill (1960), Janson (1986), Peres (1991c¢), Terborgh (1983).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.