Sapajus xanthosternos (Wied-Neuwied, 1826)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628249 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B72E-285C-0815-F611364CF6A9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Sapajus xanthosternos |

| status |

|

Yellow-breasted Capuchin

Sapajus xanthosternos View in CoL

French: Sapajou a poitrine jaune / German: Gelbbrust-Kapuzineraffe / Spanish: Capuchino de pecho amarillo

Other common names: Buff-headed Capuchin, Golden-bellied Capuchin, Smooth-headed Capuchin

Taxonomy. Cebus xanthosternos Wied-Neuwied, 1826 View in CoL ,

Rio Belmonte, Bahia, Brazil.

This species is monotypic.

Distribution. EC Brazil, S and E of the Rio Sao Francisco, S to the Rio Jequitinhonha in the S of Bahia State. View Figure

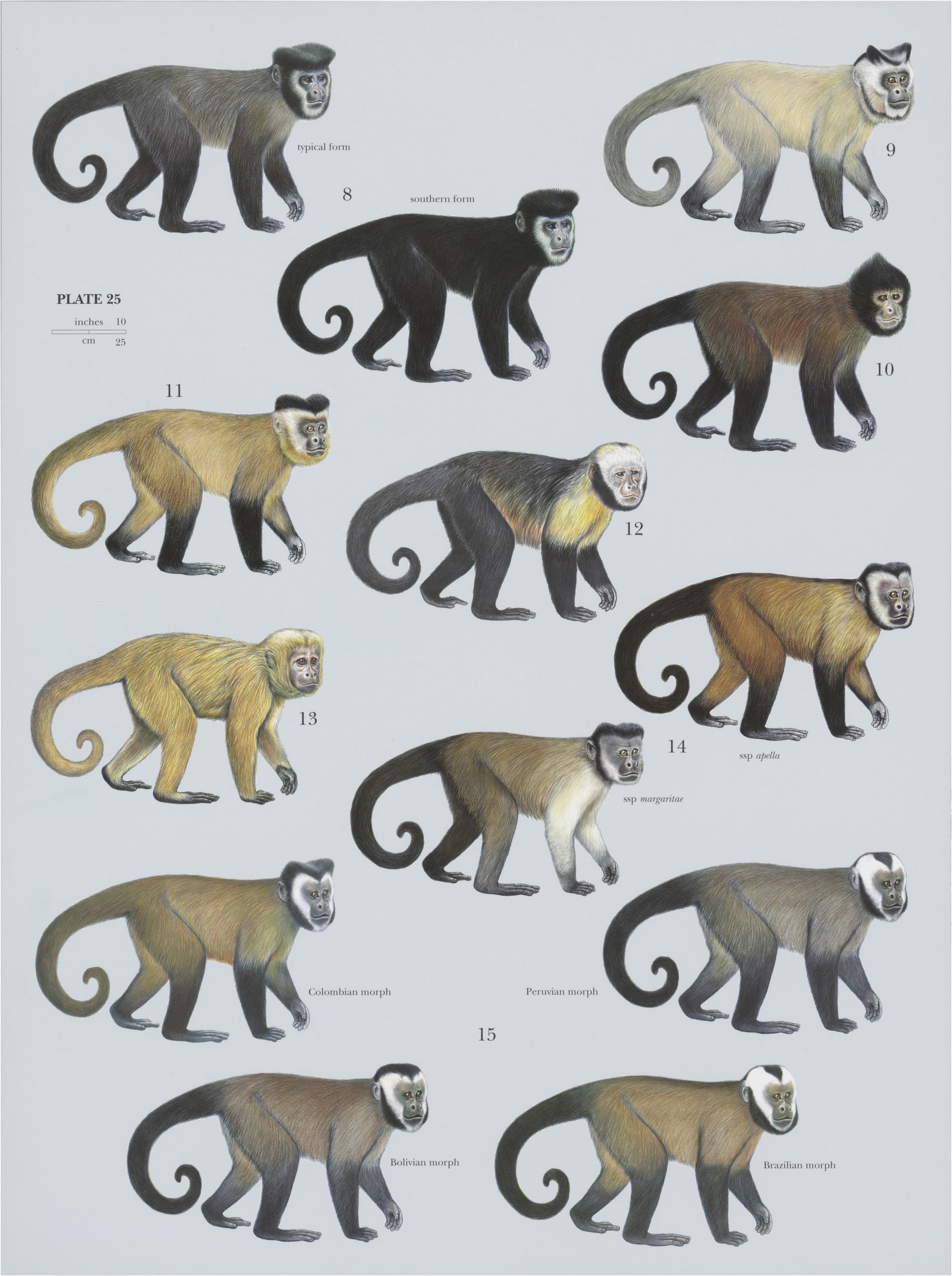

Descriptive notes. Head-body 39-42 cm (males) and 36-39 cm (females), tail 38-45 cm; weight 2.4-8 kg (males) and 1.3-3.4 kg (females). The Yellow-breasted Capuchin is generally brindled reddish above with a sharply marked, golden-red underside. The tail and limbs are black. The crown does not contrast with the body, the cap is black, and the face and temples are fawn. It is sometimes considered to be an exception among the robust/tufted capuchins because it lacks tufts, but it does in fact have small backward pointing tufts when inspected more carefully. In the northern part ofits distribution, Yellow-breasted Capuchins tend be pale, and in the south-west in the north of Minas Gerais State, they are considerably darker in overall color.

Habitat. Humid tropical lowland and submontane forest and, in the western part of its distribution, dry, semi-deciduous and deciduous forest. In the caatinga, the Yellowbreasted Capuchin is restricted to hills and mountain ranges where more humid forests can be found in valleys and slopes that receive orogenic rainfall.

Food and Feeding. Yellow-breasted Capuchins eatfruits, flowers, leaves of bromeliads, palm hearts, and small animal prey, including insects, birds (and bird eggs), lizards, and small mammals. They are the largest arboreal mammals in the forests where they live and are important seed dispersers—perhaps the only seed disperser of many of the plants in their habitat. They eat fruits from 96 plant species and swallow seeds of 88 of them. They feed also on cultivated exotic species such as oil palm ( Elaeis guineensis, Arecaceae ), jackfruit ( Artocarpus heterophyllus, Moraceae ), and cacao ( Theobroma cacao, Malvaceae ).

Breeding. A primiparous female Yellow-breasted Capuchin was recorded having twins in the Rio de Janeiro Primate Center in 1997. Her two infants were carried ventrally for the first month, and then increasingly on her back. In the fifth month, the infants occasionally left their mother and sometimes were carried by other females. Weaning began at one year of age. They weighed 1-5 kg and 1-6 kg at twelve months and 1-7 kg and 1-8 kg at 20 months, and still briefly rode on the mother’s back when they felt threatened. The male did not carry the young.

Activity patterns. There is no specific information available for this species, but sleeping sites are in large emergent trees.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of Yellow-breasted Capuchins are 9-27 individuals, but it is not known to what extent small groups result from hunting. A large group of 27 individuals used a large home range of more than 1000 ha, traveling ¢.3000 m during the day, whereas a smaller group of nine individuals used 418 ha. Females are philopatric and show little aggression. Surveys in 2003 2004 provided a density estimate in three forests in southern Bahia of 3-7 ind/km?.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List (as Cebus xanthosternos ). Although there are no reliable estimates of remaining populations of the Yellow-breasted Capuchin,it is believed to be among the rarest of the Neotropical primates. Its forests were largely obliterated during colonization of the region from the early to mid-1500s. Historical records show that in 1757 the region of the Reconcavo da Bahia and the main part of the states of Bahia and Sergipe, where the Yellow-headed Capuchin once thrived, produced more than 300,000 cattle/ year,all bred in pastures that were once tall tropical forests. By 1938, only 0-1% of Sergipe State was forested. There are no localities remaining where the Yellow-breasted Capuchin is found in anything but very low densities. Moreover, they are hunted for their meat and occasionally trapped for the pet trade. The Yellow-breasted Capuchin is known to occur in Una and Mata Escura biological reserves, Serra do Conduru State Park, and Serra das Lontras National Park created in 2010. In 2005, the population in Una Biological Reserve was estimated at 340 individuals (4-4 inds/km?). A breeding program was initiated at the Rio de Janeiro Primate Center in Brazil in 1984, and the Brazilian government established an international committee for the management and conservation of the Yellow-breasted Capuchin in the wild and in captivity in 1992. Between 1990 and 2000, 21 Yellow-breasted Capuchins were sent to seven zoos in Europe. In 2000, as a result of the efforts of the Mulhouse Zoo in France, the Yellow-breasted Capuchin was managed through the European Endangered Species Programme, with no further imports. By 2010, the number of captive individuals had risen to 140 maintained in 21 zoos. Surveys of the wild Yellow-breasted Capuchins resulted in estimates of ¢.3000 individuals remaining in widely scattered localities, but none of the populations are considered viable in the long term.

Bibliography. Baker & Kierulff (2002), Canale et al. (2009), Cassano et al. (2005), Coimbra-Filho (1986d), Coimbra-Filho, da Rocha e Silva & Pissinatti (1992), Coimbra-Filho, Rylands et al. (1991/1992), Fragaszy, Fedigan & Visalberghi (2004), Fragaszy, Visalberghi et al. (2004), Freese & Oppenheimer (1981), Kierulff et al. (2008), Lernould et al. (2012), Oliver & Santos (1991), Pissinatti et al. (1999), Rylands, da Fonseca et al. (1996), Rylands, Kierulff & Mittermeier (2005), Seuanez et al. (1986), Sick & Teixeira (1979), Torres (1988).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.