Saimiri sciureus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628239 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B720-2852-08F0-FD8D3965F641 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Saimiri sciureus |

| status |

|

Guianan Squirrel Monkey

French: Saimiri écureuil / German: Guayana-Totenkopfaffe / Spanish: Mono ardilla comun

Other common names: Common Squirrel Monkey; Collins's Squirrel Monkey (collinsi)

Taxonomy. Simia sciurea Linnaeus, 1758 ,

“India.” Restricted by Tate in 1939 to Guyana, Kartabo.

S. sciureus has seven pairs of acrocentric chromosomes. S. s. collinsi was recognized by A. Cabrera in his catalogue of primates in 1958 and W. C. O. Hill in his review of the Cebidae in 1960. Modern revisions of squirrel monkey taxonomy by P. Hershkovitz, R. Thorington, Jr. in 1985, and C. P. Groves in 2001, however, listed it as a junior synonym of the nominate subspecies sciureus . Independent molecular genetic studies by A. Lavergne and coworkers and X. Carretero-Pinzon and coworkers (both in 2009) found collinsi to be distinct. There is some hybridization with S. ustus in the maze of channels and flooded forests between the rios Madeira and Purus, just south of the Amazon River. Two subspecies recognized.

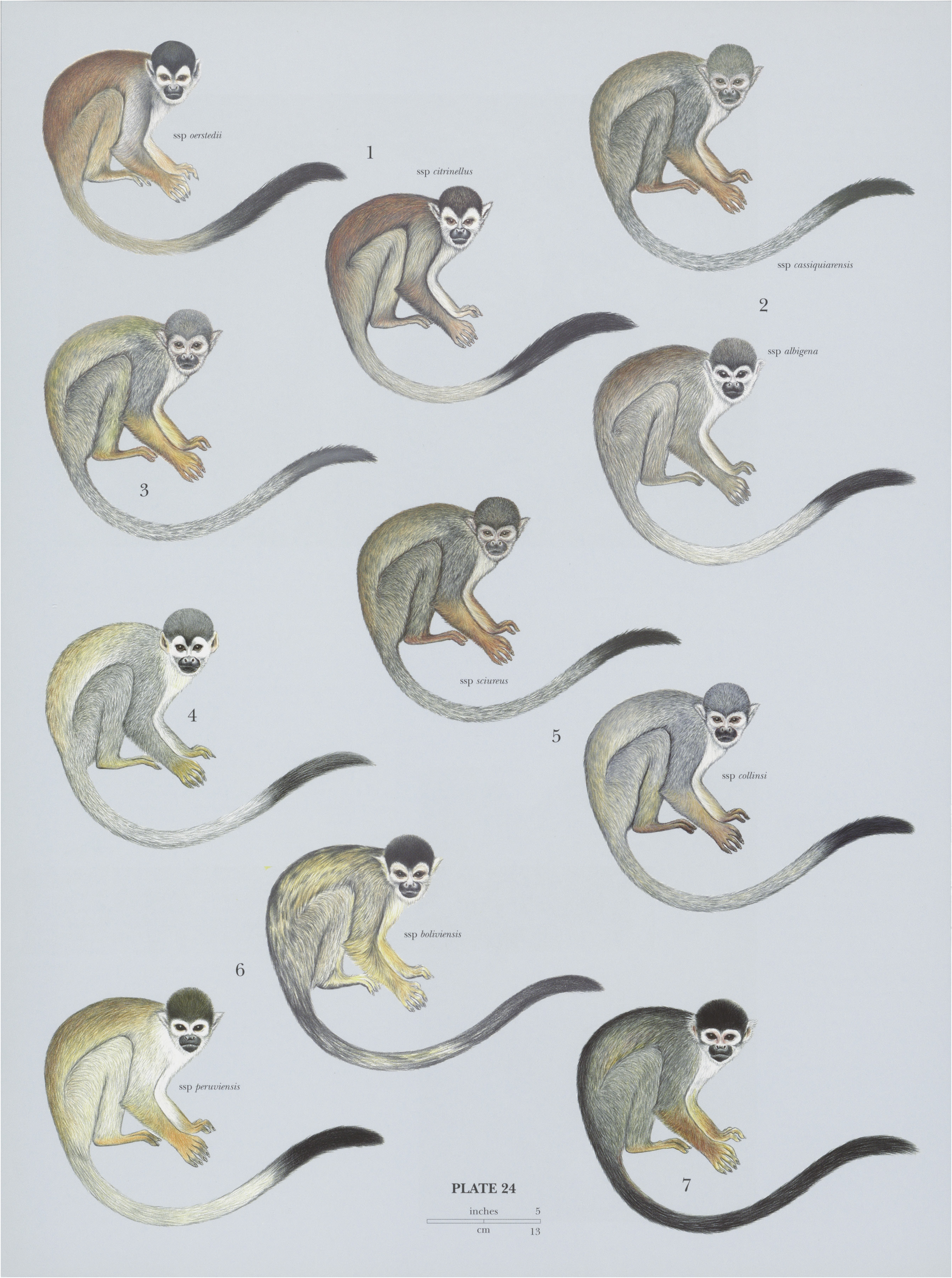

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. s. collins: Osgood, 1916 — N Brazil, Marajo I in the estuary of the Amazon River (Para State), but further studies are needed to identify the extent of its occurrence, which may well be much larger; the identity of the squirrel monkeys on other islands in the Amazon estuary (Gurupa, Caviana, and Mexiana) has yet to be ascertained. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 25-37 cm (males) and 25-34 cm (females), tail 36— 40 cm (males) and 36-47 cm (females); weight 550-1400 g (males) and 550-1200 g (females). The adult male type specimen of “Collins’s Squirrel Monkey” (S. s. collinsi): head-body 24-9 cm and tail 41-1 cm. The Guianan Squirrel Monkey is generally grayish or greenish to reddish-agouti, with an agouti-colored crown. White arches over the eyes are high and pointed in the “Gothic arch”style, and there are white ear tufts. The face is pink, with black around the muzzle. The nominate subspecies sciureus is buffy-agouti with yellowish-orange forearms, hands, and feet, and a white underside. The crown is gray-agouti in the male and intermixed or bordered with black in the female. Individuals south of the Amazon River are slightly yellower on the back and have a more yellowish suffusion on the crown. There is no defined nuchal band. Collins’s Squirrel Monkey is similar to the nominate subspecies, but its hands and feet are a dark rich tawny compared with the golden yellow or orange of the nominate subspecies. White around the ears is not (or only narrowly) continuous with white around the eyes. The back is paler than in the nominate subspecies, and the head, shoulders, and forepart of the back are grayish.

Habitat. Mature forest and early and late successional stages of secondary lowland rainforest, seasonally inundated forest, river edge and gallery forest, and mangrove and swamp forest.

Food and Feeding. A. Stone studied the feeding ecology of two groups of Guianan Squirrel Monkeys at Ananim, east of Belém, in the Para State, Brazil. Their diets were principally insects, fruit, flowers, nectar, seeds, gums, spiders,lizards, and bird eggs. Insects accounted for 79-82% oftheir feeding and foraging times during the year. Insects contributed more to the diet in the dry season: 72-74% of the time spent feeding and foraging in the dry season compared to 50-51% in the wet season. In one year, squirrel monkeys ate fruits from 68 species and 37 families. The fleshy, yellow mesocarp of fruits of the palm Maximiliana (= Attalea ) maripa ( Arecaceae ) was preferred, comprising an average of 28% of their feeding time and ranking first or second in the diet for nine months of the year. These palms grow in clusters, each having one to four bunches of several hundred to over one thousand fruits, which allows an entire group to feed simultaneously. In the wet season, flowers contributed only 1:7% of the plant diet, but they rose to 28-5% of the diet in the dry season when fruits were scarce. The two most important species providing flowers were the liana Memora magnifica ( Bignoniaceae ) and the vine Passiflora glandulosa ( Passifloraceae ). Nectar was eaten in the dry season, and they also ate gum and small (less than 4 mm) seeds of Stryphnodendron pulcherrimum ( Fabaceae ), which in one month comprised 39% of the plant feeding records. Of the insect prey recorded, 51% were orthopterans, but caterpillars and Hymenoptera were important in the wet season. In the dry season, Guianan Squirrel Monkeys frequently foraged in leaflitter (32% of insect foraging records) for large orthopterans and hemipterans, but only rarely in the wet season (2% of records). Another study of their diet was carried out by E. Lima and S. Ferrari in Gunma Ecological Park, also in the south of Para. The study monitored the diet of a group of Guianan Squirrel Monkeys in lowland terra firma forest through the dry season (August-November) to the onset of the wet season (December—January). In contrast to the findings of Stone, the diet changed markedly during the study. Animal prey (mostly orthopterans and lepidopterans) accounted for 80% of the feeding records in August, while plant material (mostly fruit) accounted for 20%. These proportions gradually changed as the dry season progressed, with less animal prey and more fruit until January, in the early wet season, when animal prey comprised 20% of the diet and fruit 80%. Foraging success for animal prey declined progressively through the study, while numbers of trees in fruit gradually increased. Overall, they ate fruit from 21 species, nectar from Symphonia globulifera ( Clusiaceae ), and inflorescences of Cecropia (Urticaceae) . Almost one-half of fruits eaten came from species of Fabaceae and Sapotacae. The Guianan Squirrel Monkey has been seen eating a bat only once, so it evidently does not hunt for them systematically as does the Central American Squirrel Monkey (S. oerstedii ).

Breeding. Breeding of the Guianan Squirrel Monkey is seasonal and normally synchronous in the group. Prior to the mating season, adult males become considerably fatter on the upper parts of their bodies, and they are much more vocal and aggressive. The mating season lasts about nine weeks in the early dry season. Unlike the Central American Squirrel Monkey, female Guianan Squirrel Monkeys apparently do not present sexually to males, nor do they follow or call to them. After a gestation of five months, births are highly synchronized among group members (all in less than one week) over two months (January-February) in the early wet season. The single large offspring is cared for by the mother and other adult females (allocare or alloparenting) that carry infants for short periods. The father shows no paternal care. The infant’s tail is slightly prehensile. Infants are weaned by about six months. Females are sexually mature at c.2:5 years and have their first infants about one year later. Males go through a subadult phase before entering true adulthood at 4-5 years old. Interbirth intervals are 1-2 years. Guianan Squirrel Monkeys can live 20 years or more.

Activity patterns. A study of two groups of Guianan Squirrel Monkeys in eastern Brazil found that, on average, 51-53% of their days is spent foraging for, processing, and eating food during the year. In another study, activity budgets were slightly different between seasons. In the dry season, individuals foraged more for insects (c.31% vs. c.25%), spent more time eating (¢.23% vs. ¢.15%), and less time resting (c.17-5% vs. c.27%) and occupied in social behavior (¢.5% vs. ¢.8%) than in the wet season. Time spent traveling (c.22% of the day) was similar between seasons.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The two groups of Guianan Squirrel Monkeys studied by Stone at Ananim had 44 and 50 individuals. During one year, their home ranges were 110 ha and 123 ha, with little seasonal differences in home range use. Daily movements were more than 2 km, averaging 2347 m during 57 days for one group and 2290 m during 20 days for the other. Groups are multimale—multifemale, with each sex forming dominance hierarchies; males are typically larger and most or all are dominant over females. Male Guianan Squirrel Monkeys form coalitions . Groups studied in Suriname have frequent agonistic interactions, and commonly over fruits (1-5 interactions/hour). Males in the groups studied in Brazil were much less aggressive. Aggression between femalesis infrequent, and they do not form coalitions . Females disperse and males are philopatric. Groups of Collins's Squirrel Monkey in gallery forest along the Rio Jutuba in the savanna of the eastern part of the island of Marajo were smaller (average 10 ind/group) than in extensive forest lowland terra firma forest. This is similar to the “Colombian Squirrel Monkey” (S. cassiquiarensis albigena) in gallery forest of the Eastern Llanos in Colombia, which also has smaller groups, perhaps an adaptation to the occupation of restricted linear habitats. Densities of Collins’s Squirrel Monkey have been estimated at 5-2 groups/km? and 54-2 ind/km?.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. Collins’s Squirrel Monkey is not evaluated separately. The Guianan Squirrel Monkey is widespread and common, although it was extensively exploited in the past by the laboratory-animal and pet trades. It is rarely hunted. It occurs in numerous and many large protected areas within its distribution.

Bibliography. Boinski (1999a, 1999b), Boinski & Cropp (1999), Carretero-Pinzén et al. (2009), Fernandes et al. (1995), Groves (2001), Hershkovitz (1984), Hill (1960), Jones et al. (1973), Lavergne et al. (2009), Lima & Ferrari (2003), Peres (1989c), Podolsky (1990), de Souza et al. (1997), Stone (2007), Tate (1939), Thorington (1968b, 1985).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.