Nyctophilus gouldi, Tomes, 1858

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6397752 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6403467 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4C3D87E8-FFD6-6A69-FF7C-92CD16BCBC0D |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Nyctophilus gouldi |

| status |

|

82. View Plate 58: Vespertilionidae

Gould’s Long-eared Bat

Nyctophilus gouldi View in CoL

French: Nyctophile de Gould / German: Gould-Langohrfledermaus / Spanish: Nictofila de Gould

Taxonomy. Nyctophilus gouldi Tomes, 1858 View in CoL ,

Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia.

Nyctophilus gould : is in the gould: group, which also tentatively includes N. sherrin: and N. nebulosus , but this requires additional research. Pilbara specimens of N. daedalus might be a distinct species within the gouldi group based on morphology. The Western Australian population might represent a distinct species with additional research. Monotypic.

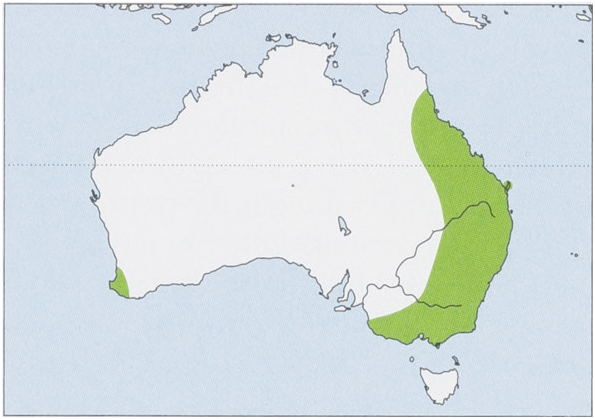

Distribution. SW Western Australia, E & SE Queensland (including Fraser I), C & E New South Wales, Victoria, and SE South Australia, SW & E Australia. A specimen is known from Fiji, but this is suspected to represent the New Caledonian Long-eared Bat ( NV. nebulosus ) or a mislabeled specimen. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 44-52 mm, tail 39-41 mm, ear 24-3-30-1 mm, forearm 36-3—47-7 mm; weight 5-2-16-5 g. Individuals from the south seem to be much larger than individuals in the north. Gould’s L.ong-eared Bat has very large ears and unique simple noseleaf of two ridges, one further on muzzle and another immediately above nostrils, with vertical groove in middle and furred trough between them. Dorsal pelage is slategray to grayish brown; venteris ashy gray. Rostrum,ears, and membranes are dark grayish brown. Rostrum is short and blunt, with ridge across muzzle over nostrils that is moderately developed with slight vertical groove. Ears are very large and broad, with bluntly rounded tips, horizontal ribbing on inner surfaces, inward curved anterior edges, and smooth posterior edges (ears can fold back at top ofthick part of anterior edge); large and furred interauricular band crosses forehead between ears; tragus is small and bluntly rounded at tip, being convex on anterior margin. Glans penisis divided by longitudinal groove into two cylinders, with upper one projecting to give distinctly beak-like appearance. Baculum is 3-3-7 mm long, with moderately thick and short shaft that constricts to very narrow and more pointed tip in dorsal view, and base is bifurcated; in lateral view, baculum is curved downward at base, but shaftis straight to abruptly narrowed tip. Skull is robust butis relatively gracile and narrow compared with congeners; rostrum is relatively short and less massive than in major species group; tympanic bullae are moderately developed; and M? and lower molars are not reduced. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 44 and FN = 50.

Habitat. Wet to semiarid habitats, including rainforests, wet and dry sclerophyll forests, Melaleuca (Myrtaceae) woodlands, waterways lined with river red gum ( Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Myrtaceae ), woodlands, and Acacia (Fabaceae) shrublands from sea level up to elevations of ¢. 1240 m (in Victoria). Gould’s Long-eared Bat is confined to more humid, temperate regions in Western Australia. It seems to need dense understories in tall forests to establish roosts.

Food and Feeding. Gould’s Long-eared Bat is insectivorous and generally forages on the wing or by gleaning prey from foliage or the ground. Echolocation and active listening are used to detect prey, but they more readily use active listening, only really using echolocation for orientation in unfamiliar habitats. Use of active listening vs. echolocation counters evasive actions of sonar detecting flying insects by avoiding their detection as a whole—common adaptation of bats with large ears. This is not the case for insects on foliage or the ground that can be detected either by using specialized echolocation that allows it to detect details in the texture of their immediate surroundings (e.g. camouflaged moth on leaf) but is less useful in detecting speed and direction of flying prey. Gould’s LLong-eared Bats fly close to the ground when hunting and fly slowly in large circles, well below the canopy. Diets usually contain moths and beetles, but crickets,flies, cockroaches, ants, bugs, and spiders are also eaten.

Breeding. Gould's L.ong-eared Bat breeds once a year and has 1-2 young in late spring or early summer; twinning rate is 50% in late October. Spermatogenesis begins in summer, and sperm is stored in the epididymides thereafter. Mating takes place largely in April when males and females are hibernating. Males arouse to mate with torpid females sporadically through winter until September. In September, hibernation follicle matures, and ovulation, fertilization, and implantation occur. Females most likely store sperm in their reproductive tract until then. An experimental group of females that was kept at 22°C in winter gave birth to young 67 days before wild individuals that were hibernating over winter did. Young are fully furred by four weeks of age and make their first attempts at flying with their mother at this time. Young are weaned at c.6 weeks of age and can be seen flying in January together with novice fliers presumably from the same colony, generally accompanied by an adult or two. Females reach sexual maturity at 7-9 months and males at 12-15 months.

Activity patterns. Gould's LLong-eared Bats roost in tree hollows and fissures close to the ground by day and leave roosts around dusk to forage. They have also been recorded in roofs and possibly a cave in northern Queensland. In southern populations, they tend to hibernate in a torpid state in winter (April-September) for stretches of up to eleven days, living on fat stored during late summer and early autumn. They also enter torpor to various degrees during the day to save energy. Males in New South Wales switched between torpor and normothermic thermoregulation during the day based on temperature achieved in roosts by the sun (arousing at higher temperatures). These males appeared to gain an energetic advantage by roosting in poorly insulated and generally sun-exposed roosts. Call shape is steep FM sweep that cannot be easily distinguished from other longeared bats using typical recordings. Peak frequencies are 50-53 kHz (mean 51-8 kHz).

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Gould’s L.ong-eared Bats roost in colonies that are typically sex-segregated, with females roosting in groups of 20 or more individuals and males roosting alone or in transient groups of less than six. They switch roosts often, generally between a set oftrees close to a creek line. Nightly foraging areas were no larger than 80 ha in a small remnant patch of forest in an urban matrix with artificial light, and individuals moved on average less than 300 m from their roosts each night. They used up to 100% of the remnant forest and almost never entered urban areas, indicating that urban areas might have restricted foraging range of these bats. At the population level, there are many females that are related to one another, suggesting low female dispersal and some sort of social bond among females.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Gould’s Long-eared Bat is widespread and common throughoutits distribution. It might be threatened by forest thinning and habitat fragmentation from urbanization and agricultural expansion in some regions. It does not do well in urban environments, and artificial light might restrict foraging in urban/bushland matrixes.

Bibliography. Brigham, Francis & Hamdorf (1997), Churchill (2008), Churchill et al. (1984), Ellis et al. (1989), Fullard et al. (1991), Fuller (2013), Gee (1999), Grant (1991), Law, Turbill & Ford (2008), Lunney etal. (1988), Parnaby (1987 2002a, 2009), Pennay et al. (2008), Phillips & Inward (1985), Threlfall et al. (2013a, 2013b), Tidemann & Flavel (1987), Turbill (2006b), Volleth & Tidemann (1989), Webala et al. (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Nyctophilus gouldi

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Nyctophilus gouldi

| Tomes 1858 |