Sillago suezensis, Golani & Fricke & Tikochinski, 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222933.2013.800609 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/426D8780-5D62-E50C-FD95-FCD0FD2430B7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sillago suezensis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Sillago suezensis View in CoL sp. nov.

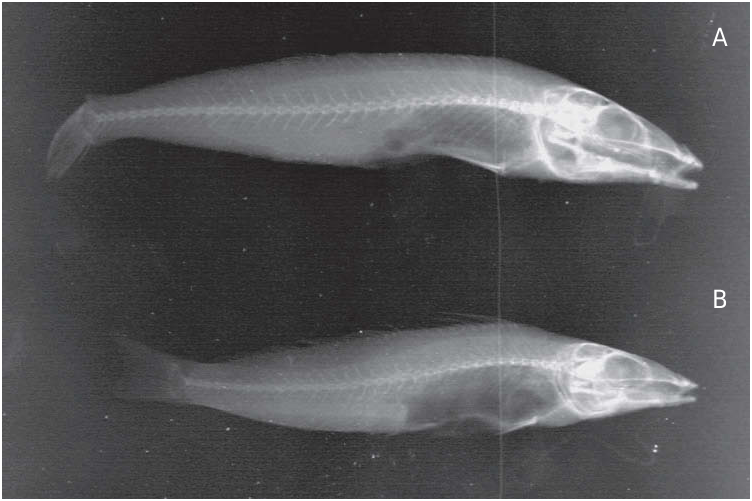

( Figures 1A, B, Dl View Figure 1 , 2 View Figure 2 , 3A View Figure 3 , 4A View Figure 4 )

Sillago erythraea: Cuvier View in CoL in Cuvier and Valenciennes 1829, p. 409 –411 (part, Gulf of Suez, based on paralectotype, MNHN A-3127). Golani et al. 2011; Tikochinski et al. 2012, p. 240 –246.

Holotype: HUJF 7134 (137 mm SL), Abu Zanima, Egypt, Gulf of Suez, Red Sea , Fish Collection team, 22 September 1967 [dissected].

Paratypes: Gulf of Suez , northern Red Sea, Egypt : HUJF 7135 (one specimen, 144 mm SL), Abu Zanima , Fish Collection team, 30 April 1970 [dissected] ; MNHN A-3127 (163 mm SL), paralectotype of S. erythraea Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes 1829, Suez , leg. E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, c.1799–1801. – Mediterranean Sea, Israel : HUJF 8552 (two specimens, 114–122 mm SL), Haifa , J. H. Fischthal, 27 June 1977; HUJF 10579 (16 specimens, 141–160 mm SL), Haifa , A. Ben-Tuvia, 27 May 1989; HUJF 10860 (two specimens, 144–185 mm SL), Haifa , A. Ben-Tuvia, 18 May 1982; HUJF 10898 (one specimen, 158 mm SL), Acre , A. Ben-Tuvia, 11 August 1982 ; HUJF 10899 (three specimens, 144–169 mm SL), Haifa , A. Ben-Tuvia, 14 January 1982; HUJF 10962 (five specimens, 109–139 mm SL), Jaffa , D. Golani, May 1980 ; HUJF 12360 (two specimens, 164–167 mm SL), Acre , D. Golani, 8 May 1987 ; HUJF 13933 (six specimens, 131–142 mm SL), Jaffa , D. Golani, 18 October 1989 ; HUJF 19740 (40 specimens, 110–162 mm SL), Haifa , D. Golani, 3 April 2008; MNHN 2012–0273 About MNHN (four specimens, 127–128 mm SL), Haifa , D. Golani, 6 June 2012; SMF 34724 (four specimens, 124–148 mm SL), same data as MNHN 2012–0273 ; USNM 406760 About USNM (four specimens, 128–138 mm SL), same data as MNHN 2012–0273. – Mediterranean Sea, Turkey : SMNS 16702 About SMNS (one specimen), Karataş, between Ada and beach, east of port, Province Adana , 1995.

Diagnosis

The following combination of characters distinguishes S. suezensis from congeners of the S. sihama species-group, which has the swimbladder divided posteriorly into two tapering extensions projecting below the vertebral column extending into the tail musculature; absence of scales on the preoperculum and on most of the operculum; total number of vertebrae 34; swimbladder with lateral extensions each spreading a blind tubule anterolaterally; position of nostril low.

Description

First dorsal-fin rays X (X–XII); second dorsal-fin rays I, 21 (I, 19–22). Anal-fin rays II, 20 (II, 18–22). Pectoral-fin rays 17 (14–17). Lateral-line scales 67 (63–74). Vertebrae 13 (13) [abdominal] + 3 (3) [modified] + 18 (18) [caudal], total 34 (34). Gill rakers relatively large, 4 + 10 (3–4 + 8–10), uppermost raker on upper arch rudimentary. Measurements of the holotype and paratypes see Table 1.

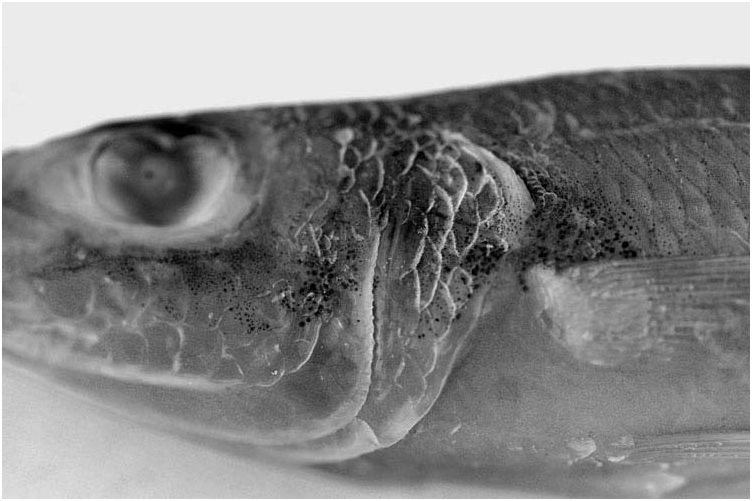

Upper jaw with a series of very small teeth that are slightly recurved. Anterior teeth slightly larger, posterior teeth gradually smaller. Teeth similar in the lower jaw, but with a narrow gap at the symphysis. Vomer covered with small teeth, similar to those in the jaws. Preopercle smooth, completely scaleless; opercle with a few scales, mainly in the upper part. Nostrils situated at the level of the upper quarter of the orbit; anterior nostril with a small flap, posterior nostril (which is situated close to the first) nearly round. Head length 3.2–3.8 in standard length. Orbit diameter 3.6 (3.0–4.3) in head length. Predorsal length 2.7 (2.6–3.2) in SL. Preanal length 1.6 (1.6–2.1) in SL. Maximum observed SL 185 mm.

Swimbladder ( Figure 4A View Figure 4 ) with two anterior extensions extending forward and diverging to terminate on each side of the basioccipital above the auditory capsule; two lateral extensions commence anteriorly, each sending a posterior subextension anterolaterally and then extending along the abdominal wall below the investing peritoneum to just posterior of the duct-like process; two posterior tapering extensions of the swimbladder projecting into the caudal region, both equal in length; the posterior subextensions of the anterolateral extension not convoluted, without blind tubules.

Colouration

Body dorsally silvery yellow-beige, silvery white below; a mid-lateral, silvery, longitudinal stripe usually present; upper part of eye with a reddish brown blotch; dorsal fins dusky terminally with or without rows of dark brown spots on the second dorsal-fin membrane; caudal fin with a faint dark brown blotch each on the dorsal and ventral lobes, fin often terminally dusky; no dark blotch at the base of the pectoral fin; other fins hyaline, pelvic and anal fins whitish.

Distribution

Northern Red Sea (Gulf of Suez, Egypt). Lessepsian immigrant through the Suez Canal into southeastern Mediterranean Sea including the southeastern Aegean Sea ( Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Turkey). The species was first recorded from the Mediterranean Sea by Mouneimne (1977), as S. sihama (non Forsskål, 1775), and immediately afterwards became very common throughout the southeastern Mediterranean Sea.

Biology

In the Mediterranean Sea, this species is mainly found on sandy substrates to depths of 40 m. Juveniles and subadults (up to 120 mm TL) are very common in shallow water of sandy beaches. The species feeds on benthic invertebrates, mainly on polychaetes and, to a lesser extent, on crustaceans ( Golani et al. 2002, p. 118). The spawning season is from April to September.

In Israel, S. suezensis sp. nov. is a commercial species that is caught by trawl and trammel net.

Etymology

The name of the new species refers to the type locality, Suez ( As Suwais , Egypt) , and the restricted original distribution area in the Gulf of Suez, northern Red Sea.

Comparison

This new species differs from S. sihama in the absence of scales on the preopercle and on most of the opercle (completely scaled in S. sihama and Sillago sp. aff. sihama ; see Figures 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ), in the shape of the swimbladder with the lateral extensions each spreading a blind tubule anterolaterally (tubule missing in S. sihama and Sillago sp. aff. sihama ; see Figure 4B, C View Figure 4 ), and the position of the nostril tending to be lower than in S. sihama .

Other species with two posterior extensions of the swimbladder include S. caudicula Kaga et al. 2010 (368, figs 1–3), S. indica McKay, Dutt and Sujatha in McKay, 1985 (see McKay 1985, p. 38, fig. 5E), Sillago intermedius Wongratana, 1977 (257, pls 9–10) and S. parvisquamis Gill, 1861b, p. 505 . The new species differs from S. caudicula in having 18–22 soft anal fin rays (23–24 in S. caudicula ), 34 total vertebrae (35–36 in S. caudicula ), the body depth at origin of first dorsal fin significantly deeper than that at origin of second dorsal fin (body depth at origin of second dorsal fin slightly deeper than that at origin of first dorsal fin in S. caudicula ), and the absence of spots along the midline of the body (11 dusky spots along the midline of the body in S. caudicula ); from S. indica in the absence of lateral extensions on the main part of the swimbladder (with four to eight lateral extensions in S. indica ), and the absence of dark markings on the side (a dark band on the side which is sometimes broken into blotches in S. indica ); from S. intermedius in the absence of dark saddles along the back (with eight to ten dorsal saddles in S. intermedius ), and the absence of spots or blotches along the midline of the body (eight or nine dark spots or blotches along the midline of the body in S. intermedius ); and from S. parvisquamis in having smooth lateral extensions of the swimbladder (lateral extensions covered with numerous blind tubules in S. parvisquamis ), the 19–22 anal fin soft rays (22–24 in S. parvisquamis ), and 63–74 lateral line scales (70–84 in S. parvisquamis ).

The species of the genus Sillago with two posterior extensions of the swimbladder are compared in Table 2.

Remarks

Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes (1829, p. 409–411) discussed the history of usage of the name S. sihama . He assumed that S. sihama of Rüppell differed from the Atherina sihama described by Forsskål in Niebuhr (1775) (which they doubted to belong to the genus Sillago at all) in the above-mentioned colouration details, and established the new name S. erythraea for Red Sea specimens of Sillago , based on six syntypes [MNHN A-3127 (one specimen) from Suez, Egypt; MNHN A-3137 (one specimen) from Massawa, Eritrea; SMF 324 (four specimens), the specimens described and illustrated by Rüppell (1828: pl. 3, fig 1)].

Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes (1829, p. 409–411) did not provide a very detailed description of the colour pattern of his S. erythraea . He only had alcohol-preserved specimens available, which had already been in preservative for 28–30 years (the Suez syntype), or 4–8 years (the Massawa syntype). The extant MNHN syntypes of S. erythraea were re-examined by Golani et al. (2011) and found to belong to two different species. While the Massawa specimen agreed well with the S. sihama of current usage, the Suez specimen was found to represent a separate species, S. erythraea . To provide a name for the species of Sillago occurring in the northern Red Sea, Golani et al. (2011, p. 470) designated the specimen MNHN A- 3127, which belongs to this new species, as the lectotype of S. erythraea . However, because of a previously missed lectotype designation of the specimen MNHN A- 3137 by McKay (1985, p. 7), S. erythraea is a junior synonym of S. sihama (see below). Golani et al. (2011, p. 466) were mistaken in the vertebral count. Erroneously, they missed the first (very small) vertebra, and misinterpreted the last abdominal vertebra as part of the hypural. The total vertebral counts are therefore not 32, as suggested by Golani et al. (2011), but in fact 34; the counts are corrected in the present paper.

In the present paper, we do not use the specimen MNHN A-3127 (paralectotype of S. erythraea ) as the holotype of the accordingly new species, because internal organs are missing; we chose another specimen from the Gulf of Suez, HUJF 7135 , instead .

The paralectotype of S. erythraea is partly damaged. Scales along the sides of the body are missing, so that the lateral line cannot be counted. Internal organs are missing. The first dorsal fin is abrased and nearly completely missing, but the bases of the spines are still present and can be counted. The second dorsal fin is also nearly completely missing (but fin ray bases are still present), except for the first three and the last two rays, which are complete. The anal fin spines are damaged by an extended slit through the belly, but the remainder of the rays are complete (except for a few damaged rays).

The condition of the scales on the opercle is consistent throughout the materials examined, compared with the heavily scaly opercle of S. sihama . It is also observed in living specimens. Therefore, an artificial loss or abrasion of scales just on the opercle while the other scales are still in place, because of collecting methods or subsequent treatment, and just in the material from the Gulf of Suez and the eastern Mediterranean, but not in the material from the southern Red Sea or in other areas, is highly improbable.

The illustration in McKay (1992, p. 59) of a swimbladder of a Red Sea specimen is probably based on Mediterranean material of S. suezensis . The unequal length of the posterior extensions of the swimbladder in that illustration is probably erroneous, as all specimens examined were found to have extensions of equal length.

In the Red Sea, there are several cases of species in the Gulf of Suez and / or Gulf of Aqaba which are distinct from closely related species in the southern parts. On the basis of Eschmeyer (2012), with addition of Pempheris sp. (family Pempheridae ; K. Koeda, personal communication, July 2011), a total of 59 species are known to be endemic in the northern Red Sea, including 14 species endemic in the Gulf of Suez, and 34 species endemic in the Gulf of Aqaba. The total northern Red Sea endemism amounts to about one-third of all fish species endemic in the Red Sea. The main reason for a high degree of endemism in the extreme northern part of the Red Sea is apparently the salinity level, which is higher than that of the main body of the Red Sea ( Wyrtki 1971). Fricke (1988, p. 538–540) discusses a theory of isolation of the Red Sea with speciation under a relatively high salinity level, and subsequent restriction of such species to the high-salinity waters of the northern Red Sea.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sillago suezensis

| Golani, Daniel, Fricke, Ronald & Tikochinski, Yaron 2013 |

Sillago erythraea:

| Tikochinski Y & Shainin I & Hyams Y & Motro U & Golani D 2012: 240 |

| Valenciennes A 1829: 409 |