Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2848.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/396387E7-5F07-E050-FF50-FF1BFD7EF849 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2021-08-23 12:03:19, last updated by Plazi 2023-11-04 12:39:19) |

|

scientific name |

Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870 |

| status |

|

Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870 View in CoL

Figs 3B View FIGURE 3 , 24–26 View FIGURE 24 View FIGURE 25 View FIGURE 26 , 27A View FIGURE 27

Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870: 519 View in CoL [Type locality: Italy, Naples ].

Suez Canal material reported herein: 37 samples, total number estimated as between ca. 200–500 individuals. Beets’ Great Bitter Lake samples, VIII / IX 1950, Stns 8–10, 33,?42, B3, 5 +? 1 samples with tentatively identified (empty) tube residues (see Appendix Table 2B).—Great Bitter Lake “Yellow Fleet” Ship Biofouling Samples (January 13–20, 1975), 37 subsamples, 200–500 specs (Appendix Table 2D).

Suez Canal depth and substrates: Beets’ samples: Residues of empty tubes on shells between 2.5–10.6 m, on Chicoreus erythraeus [as Murex anguliferus ], * Murex forskoehlii ; * Brachidontes pharaonis and * Gastrochaena cymbium .—Brattström & Taasen Great Bitter Lake “Yellow Fleet” ship-biofouling; on sponges; bivalves, * Brachidontes pharaonis ( Figs 3B View FIGURE 3 , 24 View FIGURE 24 ), * Malvufundus regulus , * Pinctada radiata and * Spondylus spinosus ; as well as on barnacles, crabs, bryozoans, and tunicates. (*Denotes an Indo-Pacific mollusc taxon that has migrated and established populations in the Levant Basin of the Mediterranean, i.e., a Lessepsian migrant mollusc [H.K. Mienis, pers. comm.]).

Remarks. Salmacina dysteri , originally described from boreal temperate waters (South Wales), was listed in the Cambridge Expedition Report on the Polychaeta Sedentaria ( Potts 1928) as present in the southern part of the Suez Canal and reported by Pixell (1913) and Potts (1928) from the Gulf of Suez end of the canal. Regrettably, Potts (1928) provided no details concerning his nominal S. dysteri material other than that there were especially large aggregations at the bathing place at the sites Port Taufiq 3, and Port Taufiq outside the Canal. That description is insufficient even to conjecture whether the Beets’ and “Yellow Fleet” Salmacina specimens sampled ca. 50 years later belong to the same taxon as that of Pixell (1913) or Potts (1928).

Fauvel (1933b: 144) reported Salmacina dysteri from the Gulf of Suez, citing Pixell’s (1913) and Potts’ (1928) reports, and discussed the philosophical basis for his taxonomic work: “Many species considered for a long time as endemic to the Indo-Pacific region appear absolutely identical with European species... One risks, therefore, considering as an important new species a taxon simply designated by a different name although in reality it is synonymous.” Fauvel was, very likely, the most redoubtable polychaetologist of his day, and this biogeographical philosophy presumably influenced H.L.M. Pixell (1913) and F.A. Potts (1928) as seen in their “cosmopolitan attribution” of S. dysteri (or they may all have influenced each other). Together, these authors provided an unlikely mix of distributions including those of nominal S. dysteri : The Atlantic, North Sea, English Channel, Cape Verde, Mediterranean, Red Sea, Suez Canal, Gulf of Suez, Zanzibar and Australia ( Fauvel 1927).

Regrettably, Pixell’s (1913) and Potts’s (1928) important voucher specimens from the Suez Canal could not be found, however, we were able to obtain for SEM examination Pixell’s nominal Salmacina dysteri specimens from Zanzibar and Wasin Island; one of Fauvel’s (1933a, b) samples from the Gulf of Suez; a nominal specimen of S. dysteri from Hawaii; as well as live Salmacina specimens from the Gulf of Aqaba (from Elat). Our findings did not support the determination of S. dysteri for these specimens or the ascription of S. dysteri as a “cosmopolitan species” (see “Material examined for comparison”, above). (Interestingly, Fauvel himself had some doubts as to the identification of the Gulf of Suez specimen as he put [three!] question marks after the “ Salmacina dysteri ” in his handwritten label of the voucher sample although the question marks were not cited in his two Gulf of Suez publications [ Fauvel 1933a: 80, 1933b: 1431]). On the contrary, the new findings support our cautious approach of generalising unverified determinations of Salmacina when the identifications cannot be validated by re-examining the specimens (see also Noguiera & ten Hove 2000).

Here it is important to stress that generalising the species determination applies only to the specific sample examined, as in none of the given areas was the density of sampling sufficiently great as to definitively exclude the possibility of more than one Salmacina taxon being present, particularly in the port areas, such as Port Taufiq, and even in the Suez Canal itself. As the late Prof. Heinz Steinitz noted (pers. comm.), finding a taxon in a given area is meaningful, but not having found it may not be indicative of its true absence unless high density and thorough sampling is carried out. This truism is particularly relevant concerning Salmacina and other taxa that can be transported by ship.

The type locality of Salmacina dysteri is Tenby, Carmarthen Bay, South Wales. Scanning electron microscope examination of nominal S. dysteri specimens from nearby biogeographic locations, i.e., the North Sea, the Irish Sea, as well voucher specimens from the English Channel identified by P. Fauvel (see Material examined for comparison, above), establishes that Fauvel’s particulars of the thoracic uncini of S. dysteri from its biogeographic home region—“7 rows with 2–3 teeth in a row”—were accurate ( Fauvel 1927; see also Rioja 1931 and Nogueira & ten Hove 2000), although in his figure, 129i on p. 379, Fauvel showed only a lateral view of the uncinus. Precise detail was naturally missing in his lateral illustration of the collar chaetae reported as having numerous fine teeth on the fin. Fauvel’s illustration of the S. dysteri aggregate ( Fauvel 1927, fig. 129k, a copy of Huxley 1855, fig. 1) is variously described as “a bundle of intertwining networks of tubes” ( Fauvel 1927), a “rope-like twisted mesh” (Knight-Jones et al. 1996: 256) or an “arborescent” aggregate ( Nishi & Nishihira 1997). Examination of the nominal S. dysteri tube aggregations from the Hebrides, from Menai Bridge and Fauvel-identified Saint Vaast-la-Hougue (La Manche) material bears that out.

The contrasting description of Salmacina incrustans referred to collar chaetae with 4–6 large teeth on the fin ( Fauvel 1927: 377–380, fig.129 a–l). Other than “rectangular with several rows of teeth above a larger tooth at the base,” Fauvel (1927: 378) did not provide any details of the thoracic uncini of S. incrustans . Although we were not able to obtain specimens of published S. incrustans for SEMming, we SEMmed material from traditional locations of S. incrustans from Spain and Croatia. The micrograph of the collar chaetae showed there was a prominent gap between the fin and the blade, as well as a perceptible difference in size between the prominent teeth of the fin and the other more lateral and proximal teeth. Distinct frontal views of a few thoracic uncini in a SEM micrograph of the 4 th torus of the S. incrustans from the Costa Brava specimen (SEM no. 0016), show three teeth in the F+1 row, with the number of teeth increasing to ca. 5 in the horizontal rows towards the apex. A nominal S. incrustans ’ uncinus from the Adriatic had F+1 with two teeth. For the tube aggregate of S. incrustans (type locality, Italy), Fauvel (1927: 378–379) reported two forms, either, “Tubes more or less aggregated in colonies encrusting algae, shells and stones,” or, “More rarely, forming structures analogous to those of Salmacina dysteri . ”

Fauvel reported prostomial ocelli as present in both Salmacina dysteri and S. incrustans ( Fauvel, 1927: 377, 378, respectively). However, in their study of taxonomic characters in Salmacina sp. / spp., ten Hove & Pantus (1985) found that newly-collected Mediterranean specimens (not determined to species) lacked prostomial ocelli altogether. In live or freshly collected Salmacina specimens from the Gulf of Aqaba, the character, brilliant crimson prostomial ocelli was very distinctive, but we noted that the ocelli faded shortly after alcohol-preservation ( Ben-Eliahu et al. 2007). Our conclusion was that the lack of prostomial or branchial ocelli is a robust character only in live or fresh material, not to be taken into consideration when studying preserved museum specimens ( Ben-Eliahu et al. 2007). We can provide no explanation for the discrepancy between Fauvel’s finding and that of ten Hove & Pantus (1985). Nonetheless, we have confidence that the chaetal structures described above and the form of the tube aggregate are robust and durable characters despite some variability in structure.

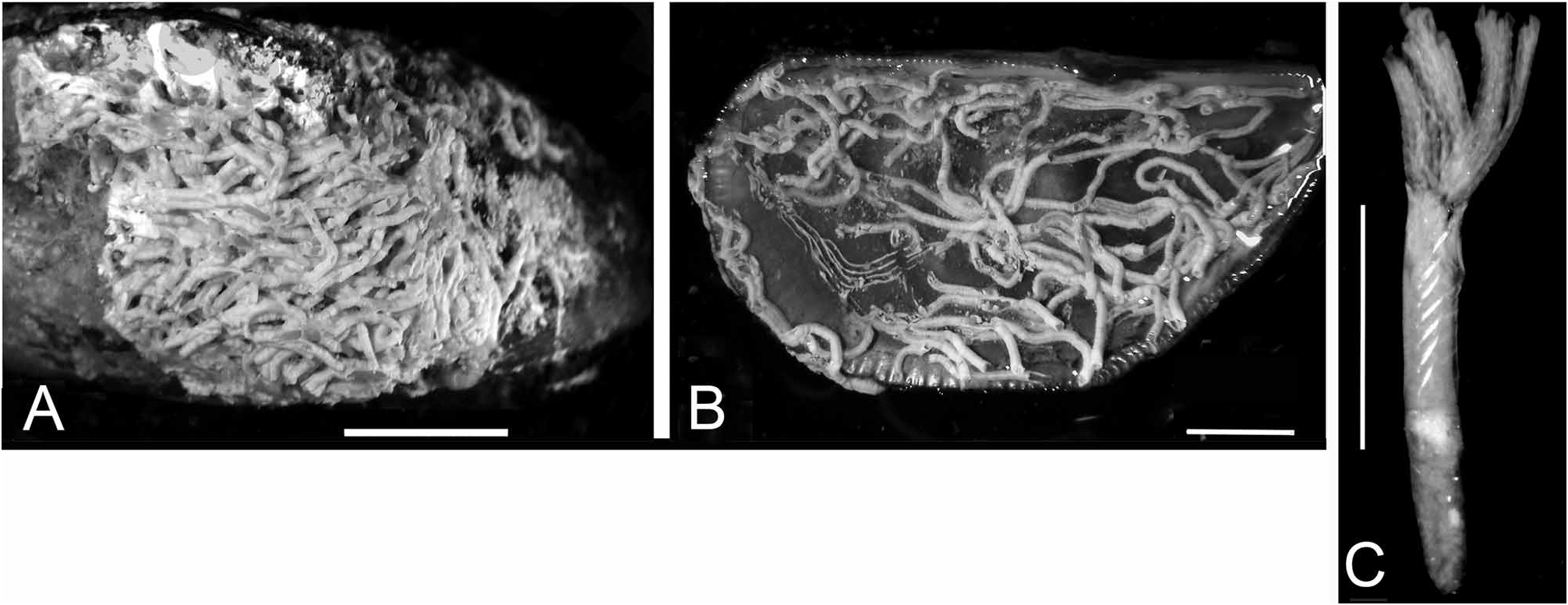

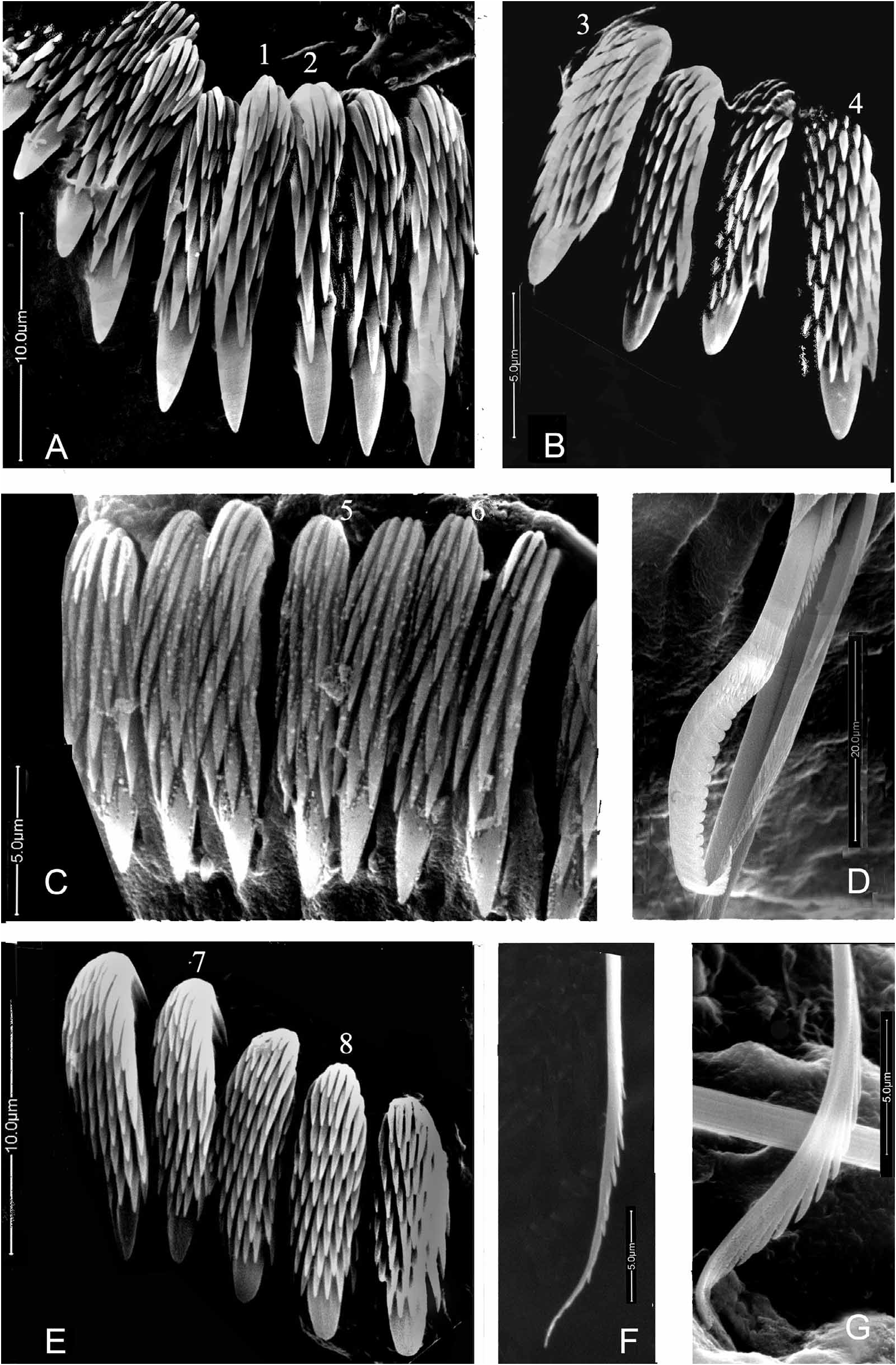

Both of our present Salmacina samples come from the Great Bitter Lake (Appendix Table 2B, D). The empty tube residues on C. Beets’ shells, collected in 1950, can be identified as Salmacina sp. due to their size and aggregate form, similar to those in Figs 3B View FIGURE 3 , 24A, B View FIGURE 24 , thus, presumably, belonging to the same taxon as the Salmacina specimens collected by Brattström & Taasen in 1975 from the “Yellow Fleet” ships. The flat- encrusting form of the tube aggregation corresponds to Fauvel’s (1927) description of Salmacina incrustans and excludes a determination of S. dysteri . The collar chaetae and uncini also conform to Fauvel’s characterisation of S. incrustans , taking into account his presumed magnification limitations. Fig. 25 View FIGURE 25 shows the collar chaetae of seven SEM “Yellow Fleet” specimens. Although there was considerable variability in their structure, even within a single fascicle (e.g., Figs 25D View FIGURE 25 1–3, F 1–2 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 ), there were nonetheless consistent characteristics: (1) the chaeta has a distinct non-denticulate gap separating the basal fin from the blade; (2) ca. 4 particularly large teeth on the fin, the distal-most tooth being the largest, the other three teeth grading in size proximally in the midline; the teeth grading laterally and proximally into smaller teeth, and then even smaller teeth laterally and more proximally reaching their smallest size in the most lateral and most proximal parts of the fin. Tori of thoracic uncini of two specimens are shown in Figs 26A, C View FIGURE 26 ; two uncini were counted in each torus (see legend, Fig. 26A View FIGURE 26 , uncini designated 1 and 2, and in Fig. 26 C View FIGURE 26 , designated 5 and 6, respectively). The number of teeth in the proximal row to the fang (F+1) position was 2–3, with the number increasing to 6 and 5 teeth and 4 and 5 teeth in the widest rows, respectively, altogether 6–7 rows of teeth above the fang (for counts of the abdominal uncini, see Figs 26B and E View FIGURE 26 ). There was considerable variability in structure between the uncini even within the same torus. Both the uncini and the flat-encrusting tube structure of our Salmacina from the Bitter Lake differ from Fauvel’s specimen from the Gulf of Suez ( Fauvel 1933 a, b) and from that in the Gulf of Aqaba ( Figs 27B, E View FIGURE 27 , respectively), as well as from a nominal S. dysteri from Hawaii. With less trepidation than before attempting this comparative study, we feel able to identify our Bitter Lake specimens as S. incrustans sensu Fauvel (1927) . Salmacina incrustans had been recorded from Alexandria (101 m), ca. 225 km west of the Mediterranean opening of the Suez Canal ( Fauvel 1937: 47 [again, voucher specimens not available]). Presuming that our determination as S. incrustans from the “Yellow Fleet” population in the Bitter Lake was correct, it is a reasonable inference that this taxon was transported by the ships from the Atlantic and Mediterranean into the Suez Canal, and eventually “infected” the Great Bitter Lake, as most probably did two other biofouling taxa, Hydroides elegans and H. diramphus (see above).

As regards the Salmacina dysteri sample misidentified by Fauvel from the Gulf of Suez (1933a, b; Figs 27B–D View FIGURE 27 ), it is worth mentioning that the tube aggregation resembled that of the S. dysteri , e.g., from the English Channel (Manche, St. Vaast-la-Hougue (see Comparative material studied). Fauvel’s sample contained only a single worm, the one we SEMmed, however, the micrograph clearly showed thoracic uncini of the multidentate-rasp-shaped type, with four teeth in the row proximal to the fang (F+1) = 4 ( Fig. 27B View FIGURE 27 ), rather than the 2–3 teeth characteristic of S. dysteri ; thus, it is certain that this Gulf of Suez specimen was not S. dysteri s. str. despite the similar tube aggregation structure. An important implication of this finding is that the presence of an aggregation of netlike intertwining tubes (presumably the basis for Fauvel’s identification), is not exclusively diagnostic for S. dysteri . Our results indicate that the character is present in additional Salmacina taxa.

In the Salmacina populations from the Gulf of Aqaba, the thoracic uncini similarly have multidentate rasp-like uncini with 4–5 teeth above the fang: (F+1) = 4–5, Fig. 27E View FIGURE 27 , and net-like aggregations. This was also true for nominal Salmacina dysteri specimens from Hawaii ( Bailey-Brock 1976). Pixell’s Salmacina dysteri from Zanzibar, Tanzania, Wasin Harbour (BM(NH) 1924.6.13.152); from the bottom of S.S. “Juba” (BM(NH) 1938.7.25, 26–40); off the coast of Zanzibar, Jembani (BM(NH) 1938.7.25.41–52), and presumably also Zanzibar 1938.7.25.13–25, uncini partly covered ( Pixell 1913). In the present paper, we are not attempting to deal in detail with all these taxa, except for generalising them to Salmacina sp. —there may be more than one taxon involved. Multidentate rasp-like uncini are also present in Salmacina amphidentata not Jones, 1962 sensu Fiege & Sun (1999) from Hainan Island as well as in the Caribbean species, S. amphidentata Jones, 1962 .

Finally, as concerns tube-aggregate form, if both flat-encrusting and net-like forms of aggregate are characteristic of Salmacina incrustans as Fauvel (1927: 379) suggested, this raises the question whether the form of the aggregation can be related to ecological adaptation, for example, to hydrographic factors, i.e., to a less rather than a more protected environment?

Bailey-Brock, J. H. (1976) Habitats of tubicolous polychaetes from the Hawaiian Islands. Pacific Science, 30, 69 - 81.

Ben-Eliahu, M. N. & Hove, H. A. ten (2007) A comparison of some Salmacina populations (Serpulidae) from different biogeographic regions, 9 th International Polychaete Conference, Aug. 12 - 18, 2007, Portland, Maine, USA. Book of Abstracts, p. 93.

Claparede, E. (1870) Les Annelides Chetopodes du Golfe de Naples. Annelides Sedentaires. (Supplement). Memoires de la Societe de physique et d'histoire naturelle de Geneve, 20, 365 - 542.

Fauvel, P. (1927) Polychetes Sedentaires. Addenda aux Errantes, Archiannelides, Myzostomaires. Faune de France, 16, 1 - 494.

Fauvel, P. (1933 b) Resume analytique du memoire de Pierre Fauvel sur les Polychetes. Mission Robert Ph. Dollfus en Egypte. Annelides Polychetes. Bulletin de l'Institut d'Egypt, 25, 131 - 144.

Fauvel, P. (1933 a) Annelides Polychetes. Mission Robert Ph. Dollfus en Egypte. Annelides Polychetes. Memoires de l'Institut d'Egypt, 21, 31 - 83.

Fauvel, P. (1937) Les fonds de peche pres d'Alexandrie. XI. Annelides Polychetes. Notes et Memoires, Ministere du Commerce & Industrie, Direction de Recherches Pecheries, 19, 1 - 60.

Fiege, D. & Sun, R. (1999) Polychaeta from Hainan Island, South China Sea, Part I. Serpulidae (Annelida, Polychaeta, Serpulidae). Senckenbergiana biologica, 79, 109 - 141.

Hove, H. A. ten & Pantus, F. J. A. (1985) Distinguishing the genera Apomatus Philippi, 1844 and Protula Risso, 1826 (Polychaeta: Serpulidae). A further plea for a methodical approach to serpulid taxonomy. Zoologische Mededeelingen (Leiden), 59, 1 - 25.

Huxley, T. A. (1855) On a hermaphrodite and fissiparous species of tubicolar annelid. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, new series, 1 (1), 113 - 129.

Jones, M. L. (1962). On some polychaetous annelids from Jamaica, the West Indies. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 124 (5), 169 - 212.

Nishi, E. & Nishihira, M. (1997) Multi-clonal pseudo-colony formation in the calcareous tube worm Salmacina dysteri (Huxley) (Serpulidae, Polychaeta). Natural History Research, 4 (2), 93 - 100.

Nogueira, J. M. M. de, & Hove, H. A. ten (2000) On a new species of Salmacina Claparede, 1870 (Polychaeta: Serpulidae) from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Beaufortia, 50, 151 - 161.

Pixell, H. L. M. (1913) Polychaeta of the Indian Ocean, together with some species from the Cape Verde Islands. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (Zoology), 16, 69 - 92; London. (Vol. 5, The Reports of the Percy Sladen Trust Expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905).

Potts, F. A (1928) Zoological Results of the Cambridge Expedition to the Suez Canal. Report on the annelids (sedentary polychaetes). Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 22 (5) 693 - 705.

Rioja, E. (1931) Estudio de los poliquetos de la Peninsula Iberica. Memorias de la Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales de Madrid 2. Serie Ciencias Naturales, 2, 1 - 472.

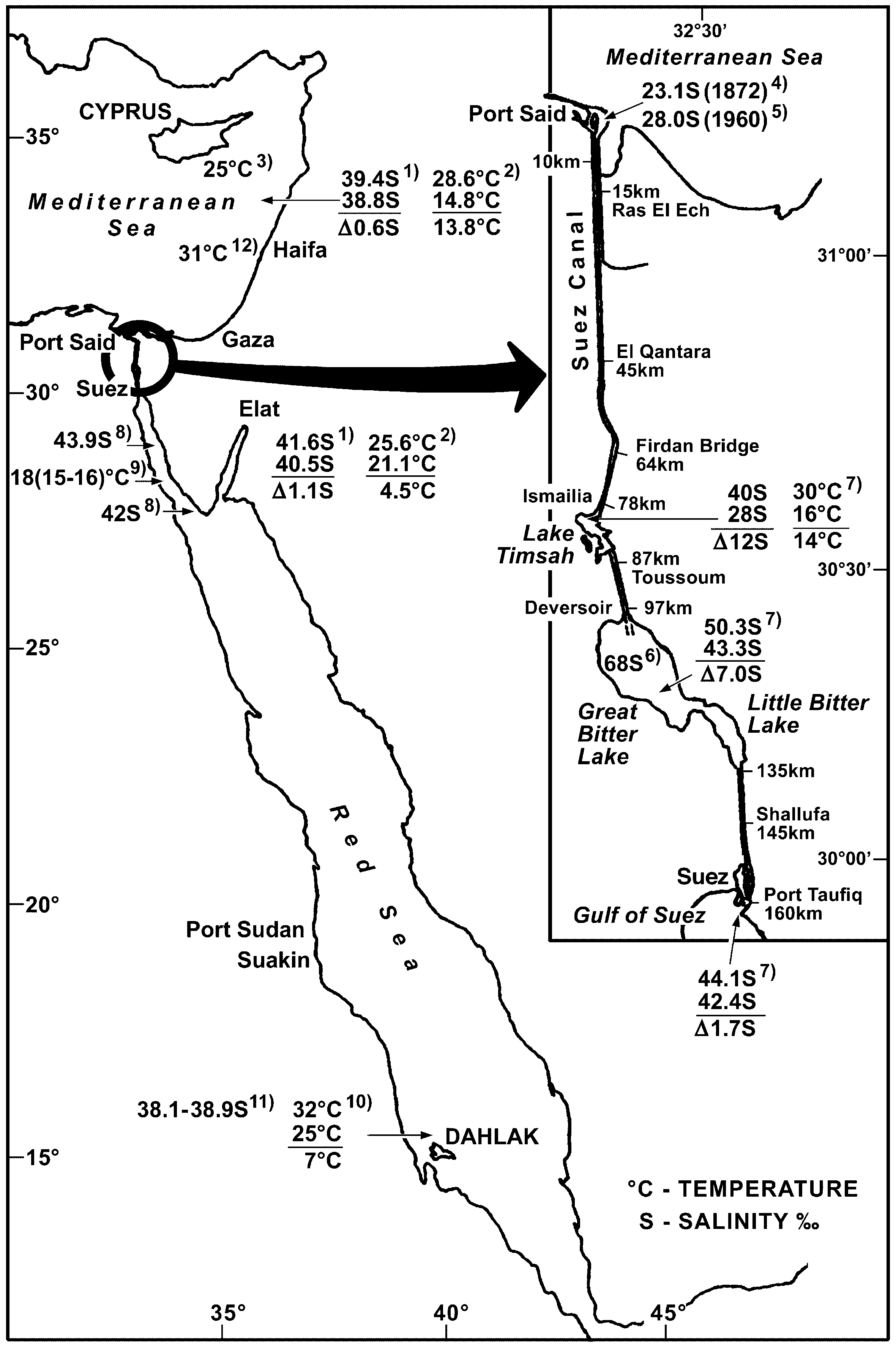

FIGURE 1. Map of Suez Canal showing salinity and temperature relations in the areas joined by the canal compiled from various sources. 1—Ben-Eliahu 1977: 70, Table 21, salinity ‰—seasonality, the extreme range of monthly means of sea surface salinity based on daily 00:08 recordings taken by the Nahariyya hydrographic station, northern Israel, 1968–1972 and the Elat hydrographic station, northern Gulf of Aqaba, 1962–1973, 2—Ben-Eliahu et al. 1988: 263, seasonality of sea surface temperature, Mediterranean coast of Israel and Elat, Gulf of Aqaba in °C (data from hydrographic stations listed above), 3—Por 1978: 118–119, fig. 32, southern Cyprus, summer surface isotherm 25°C; summer upwelling; 22°C, 4—Por 1978: 61, depressed salinity in Port Said due to Nile flood, 23.1‰ in autumn, 1872, 5—Ben-Tuvia 1970: 183, depressed surface salinity in Port Said due to Nile flood, autumn peak, IX & X.1960, 6—Thorson 1971: 842– 843, initial salinity at Great Bitter Lake, bottom, 8 m: 68–80‰; surface: 50–52‰, 7—Ghobashy & el-Komi 1981a: 169, 171, seasonality of Lake Timsah salinity and temperature between II.1977–I.1979; Ghobashy & el-Komi 1981b: 180, southern canal, seasonality of salinity and temperature at the Little Bitter Lake (Kabrit) and Suez between II.1977– I.1979, 8—Por 1972: 113–114. Gulf of Suez coast of Sinai, Ras el Missala and Ras es Sudr, 15 and 50 kms south of Suez, respectively, X.1970, Ras el Missalla along the shore, 44.25‰ and 25 m offshore 43.93‰; Ras es Sudr high VIII.1970, 44.25‰; X.1970, 41.69‰ and I.1971, 42‰, 9—Oren 1970: 226 reported 18°C temperature for the Gulf of Suez; however, Por 1972: 114, 1978: 83 noted even lower winter temperatures, particularly inshore, and found that the temperature decrease from south to north of Gulf of Suez corresponds with the depletion of the tropical fauna (i.e., of corals and associated taxa), from the south to the north of the Gulf, 10—Ben-Tuvia 1966: 255, mean monthly sea surface temperatures at Massawa, Eritrea, 11—Oren 1964: 12, table 3, III.1962, profile of Stn 7, surface to 110 m (low to high value, respectively) taken in the south Red Sea off Eritrea, off Entedebir and Dahlak Kebir Islands, 12—Brit 2000 (E. Spanier, pers. comm.): High peak temperature (9 m) prevailing off Haifa, northern Israel during August, 2000.

FIGURE 2. Biofouling on a ship that was trapped in the Suez Canal for 8 years when the canal was shut down due to the June 1967 war (adapted from Barracca & Thomas 1975). Scale: 1 m.

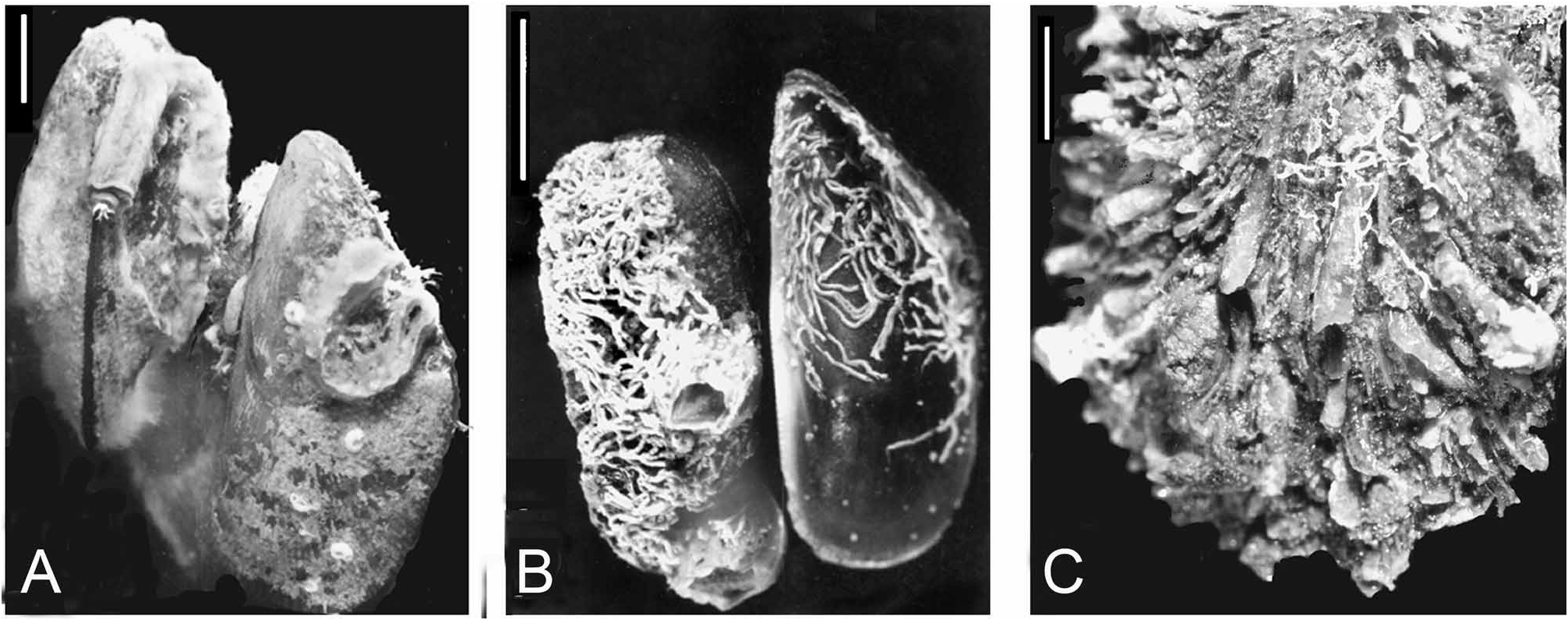

FIGURE 3. Serpulid tubeworms encrusted on bivalve molluscs from the biofouling aggregation on the “Yellow Fleet” ships trapped in the Great Bitter Lake. The aggregation on the ships was sampled in January 1975 by H. Brattström & J.P. Taasen before the reopening of the Suez Canal to traffic. A—Spirobranchus tetraceros and spirorbids on Brachidontes pharaonis; note Spirobranchus operculum projecting from upper left tube (see Fig. 33 of S. tetraceros), B—Aggregate of Salmacina incrustans and barnacle, Balanus amphitrite, on Brachidontes pharaonis, C—Minute Josephella marenzelleri tubes at base of spines of Spondylus spinosus shell (from subsample Biv 11 [see App. Table 2D]). Scales: 1 cm.

FIGURE 24. Salmacina incrustans encrusted on a Brachidontes pharaonis bivalve from the “Yellow Fleet”, Great Bitter Lake. A, B—Encrusting aggregation, outside and inside of a Brachidontes valve, respectively, C—Three-quarters view of worm (subsample Biv11). Scales: A, B–5 mm, C–1 mm.

FIGURE 25. Variability in fin and blade collar chaetae of Salmacina incrustans from the Great Bitter Lake sampled by H. Brattström and J.P. Taasen in January 1975. Note morphological variability of the fin structure in chaetae from the same individual. A1–3—Three collar chaetae (spec. no. 15), A1—Profile view, slightly darkened, A2—¾ view, A3—Frontal view of fin, B—Profile view of collar chaeta (spec. no. 8), C1–2—Frontal view of fin (spec. no. 14) with tips of blades of two chaetae to the left, D1–3—Three chaetae of spec. no. 10: D1—Frontal view of most distal fin, D2—Frontal view of fin positioned between the most distal and most proximal chaetae—the blade of these chaetae are below the focus level of the SEM and thus not visible in the micrograph; D3—¾ view of fin of most proximal chaeta, E—Frontal view of fin (specimen no. 16), F—Frontal view of fins (spec. no. 13; note the free (non-denticulate) space between the fin and the blades; the denticulate structure of the blades, G. G1—Frontal view of fin, G2—Lateral, almost profile view of fin & blade chaeta (specimen no. 11, 10,000 x). Magnifications: A1, A2—7,000 x, A3, E–G—10,000 x, B—6,000 x, C—16,000 x; D1—15,000 x; D2, D3—12,000 x.

FIGURE 26. Salmacina incrustans: Chaetae (other than collar chaetae) and uncini of specimens shown in Figs 25. A, B—Thoracic and abdominal uncini of spec. 13-3: A: Thoracic uncini (numbers refer to marked uncini in the figures): (1) F:3:4:4:5:6:6:3 = F+7 rows. (2) F:2:3:3:4:5:4 = F+6 rows, B—Abdominal uncini: (3) F:5:7:7:7:8:8:7:6:4 = F+9 rows; (4) F:5:5:6:6:3:5:6:5:5:5 = F+10 rows, C—Thoracic uncini of spec. 10-3, thoracic uncini teeth count: (5) F:3:4:4:4:4:4 = F+6 rows. (6) F:3:4:3:4:5:5:3 = F+7 rows, D—Apomatus chaeta and limbate chaetae (specimen 10-2), E—Abdominal uncini of spec. 13-2, (7) F:4:5:6:7:6:7:7:5:5 = F+9; (8) F:5:5:6:8:7:7:6:7:4 = F+9, F, G—Abdominal chaetae of two specs (15-1 and 8-1. Magnifications: A—13,000 x, B—16,000 x, C—12,000x, D—6,000 x, E—10,000 x, F—12,000 x, G— 16,000 x.

FIGURE 27. Comparison of Salmacina spp. from the Suez Canal, Gulf of Suez, and Gulf of Aqaba. A—Salmacina incrustans from Great Bitter Lake, spec. 10-3, thoracic uncini both (F+1) = 3, left uncinus detailed F:3:3:3:3:4:4 (compare Fig. 23), B—Salmacina not dysteri (Huxley) from Gulf of Suez (32°44’–32°47’ E., 28°49’–28°54 N., 25–30 m, legit R. Ph. Dollfus, Stn 11, 8.XII.1928, coralligenous sand, det. P. Fauvel (1933a: 80, 1933b: 143), generalised herein to Salmacina sp.; thoracic uncini from second torus of single (minute) specimen, apical part of uncini covered by a flap; F:4:5:5:? (left uncinus) and F:4:6:6:6:? (right uncinus), C—Collar chaeta fin, blade broken off, D—Intertwining, netlike tube aggregation from which minute specimen was removed, E—Thoracic mru-type uncini of Salmacina specimen from Gulf of Aqaba (from Elat). Magnifications: A—12,000 x, B, C—10,000 x, E—8,000 x.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870

| Ben-Eliahu, M. Nechama & Ten Hove, Harry A. 2011 |

Salmacina incrustans Claparède, 1870: 519

| Claparede, E. 1870: 519 |