Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach, 1797)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6511086 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6511096 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/29264D66-FFCA-981F-F370-28D9F866F4D6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Loxodonta africana |

| status |

|

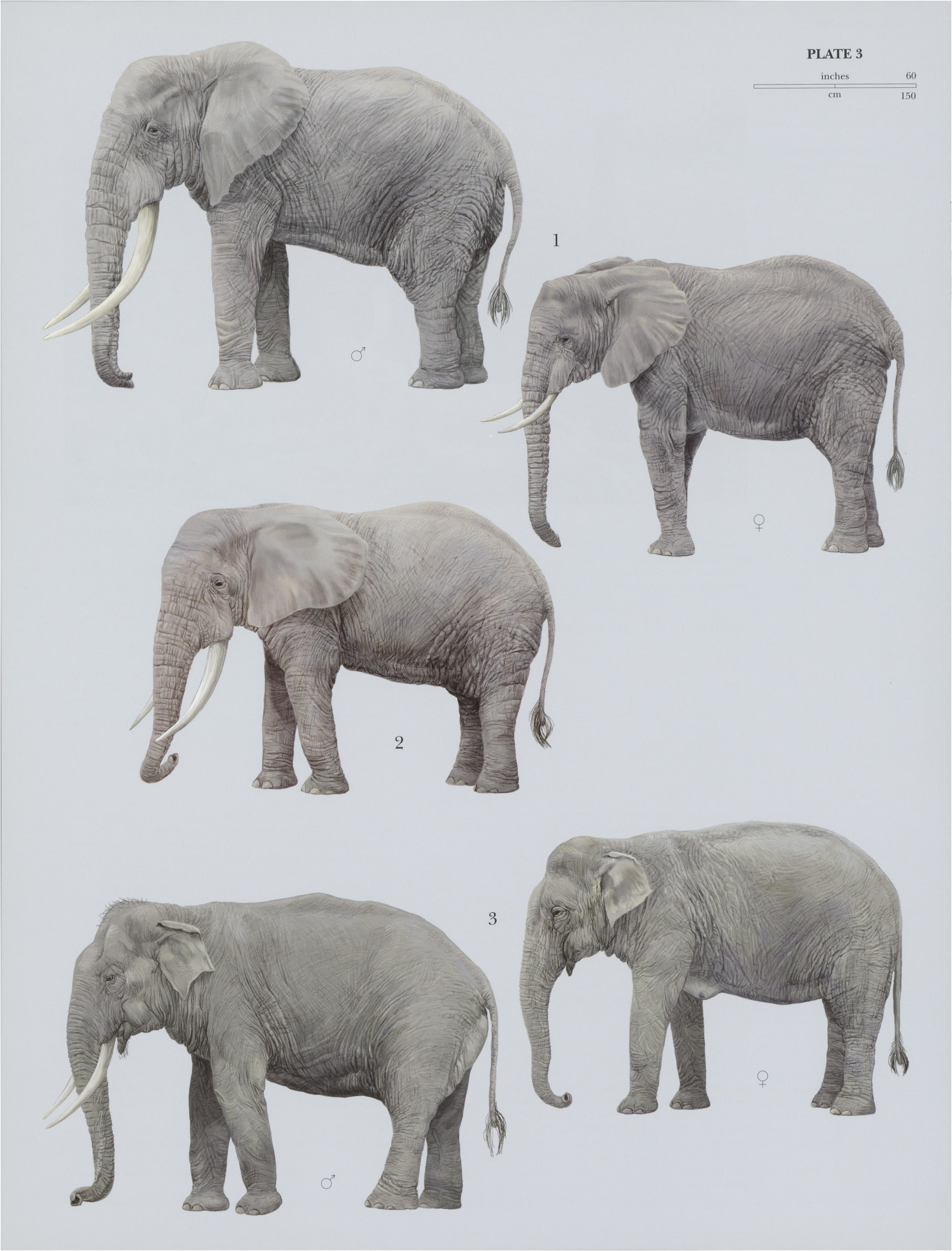

1. View Plato 3

African Savanna Elephant

Loxodonta africana View in CoL

French: Eléphant de savane / German: Afrikanischer Savannenelefant / Spanish: Elefante de sabana

Taxonomy. Elephas africanus Blumenbach, 1797 ,

Orange River, South Africa.

No subspecies are currently delineated, though size, appearance, and ivory vary regionally. Previously, the African Forest (L. cyclotis) and African Savanna Elephants were considered subspecies. Recent genetic examination indicates they are genetically distinct, meriting consideration as separate species. The delineation between African Forest and African Savanna Elephants remains contentious, and IUCN continues to recognize a single species with two subspecies. Genetic indices indicate that African Savanna Elephant populations were relatively well connected historically, but currently fragmentation is isolating populations. Monotypic.

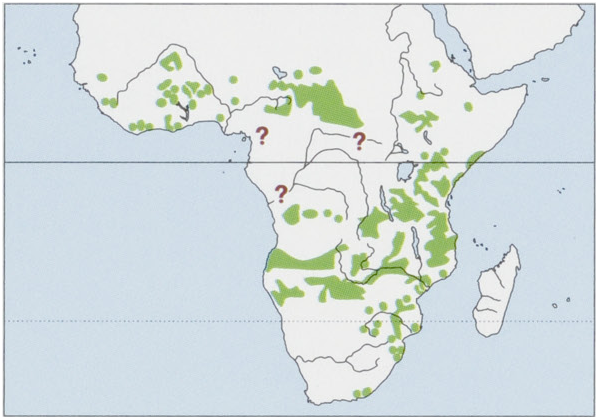

Distribution. Sub-Saharan Africa, primarily in E & S Africa. From N Cameroon and S Chad to S Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, then E Africa south to Angola, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, and South Africa. In W Africa scattered populations from Senegal to Nigeria but their taxonomic status is still under discussion. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body (including trunk) 600-750 cm, tail 100-150 cm, average shoulder height 320 cm (maximum 400 cm) in males and 260 cm (maximum 300 cm) in females; weight 6000 kg (maximum 10,000 kg) in males and 2800 kg (maximum 4600 kg) in females. Long, dense tusks are common to both females and males. Physical size and weight of ivory varies greatly across their range. Skin is thick and primarily hairless, dark gray to brown, though color varies in relation to soil (dusting and mud bathing result in soil-colored skin). Characteristic large ears are critical for thermo-regulation. Individual identification studies typically focus on nick and cut patterns on ears. Females and males are distinguishable primarily from size and girth of ivory, but also forehead shape. Males have much more bulbous foreheads; female foreheads are more angular. Large columnar legs ending in oval, padded feet support their large mass. Tails are relatively short with a bulb of hair on the end.

Habitat. African Savanna Elephants historically inhabited all but the driest desert regions of sub-Saharan Africa, including desert, mountainous tropical forest, semi-arid savanna, bushland, and dry woodland. Today they can be found in most habitats on the continent, but in greatest densities in dry wood/shrublands. Areas with elephants are typically of marginal agricultural potential or historically high disease burden. Human density is the primary driver of their distribution. Their range overlaps with African Forest Elephants on the forest/savanna fringe and it has been speculated that African Savanna Elephants probably use African Forest Elephant habitat in Central Africa.

Food and Feeding. As generalist herbivores, elephants consume a wide variety of grass and browse herbaceous materials including roots, bark, leaves,stalks, fruits, and seeds. In one account, over 150 species were ingested over a year. Food habits vary regionally in relation to resource availability. In grasslands, grass forage may comprise over 70% of the diet, while diets are totally browse-based in dense forest. In mixed wooded grassland savannas, diets switch seasonally between grass and browse in relation to productivity, resulting in nutrient content variation. Typically grass is eaten during wet season growth periods and browse is relied upon in dry season and early wet season; grass reliance can vary from 5% to 60% across seasons. Their large size and digestive structure allows elephants to metabolize low quality forage, which is hypothesized to be an adaptation to drought and low environmental predictability. As long as wateris available, adult elephants have relatively high survival rates through drought periods. Tusks are regularly used in foraging to break tree branches, debark trees, and dig up roots.

Breeding. Both males and females have reproductive cycles that strongly influence mating structure and breeding activity. For females, the 16week ovulatory cycle, capped by a 2-3 day receptive period, precedes a 22month gestation, the longest of any mammal. Highly dependentcalves stretch the postpartum interval to 1-3 years, resulting in an average intercalf interval of four years. In arid regions, reproduction is highly seasonal, with estrus typically occurring in the late wet season after peak ecosystem productivity. Estrus is dependent upon physical condition, and therefore influenced by ecological conditions (forage quality), the length of time since previously giving birth, and age. Reproductive senescence is common in old females. Males enter the physiological state of musth when reproductively active, a condition characterized by aggressive behavior, temporal gland swelling and streaming, endocrine changes, constant urine dribbling, and release of pungent pheromones. True musth (behavioral cues coupled with endocrine signatures) occurs in males over the age of 20-25 years. The duration of musth is related to dominance (size) and density of estrous females. Because males continue to grow in girth through much of their adult lives, dominant males are typically over the age of 35-40 years in populations with unaltered age structures. These males enter musth during seasonal peaks in estrous female availability and dominate reproduction in a population.

Activity patterns. Circadian activity patterns typically peak in the early morning and evening as well as around midnight. Sleep occurs primarily in the late night, around 03:00 h, for 2-3 hours. When conditions permit, day naps of 1-2 hours are common (often around noon, during the heat of the day). Foraging is the predominant activity with typically over 17 hours spent feeding per day. Time spent and rates of foraging typically increase during wet seasons when resources are higher quality. Activity may change in the presence of humans to avoid overlap at shared resources (e.g. water). The spatial relationship between limited resources is a predominant driver of activity patterns, with elephants often moving between shade, water, and forage.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. African Savanna Elephants are highly social and females maintain one of the more complex social organizations found in the animal kingdom. There are multiple (at least four) hierarchical levels, influenced by a variety offactors. Tightaffiliation in core female social groups appears to be driven by inclusive fitness benefits, socially mediated calf survivorship, social dominance relationships, and access to information. Core groups maintain strong bonds with other core groups that are usually kin-based. Further hierarchical levels appear to be related to anti-predator behavior, social factors, reproductive facilitation, and information exchange. The predominance of any of these factors can drive changes in the structure of social relations, which can occur across years and seasons. Males bond with other males, and possibly weakly to certain females, but these bonds are generally weaker than those between females. Male-male bonds are apparent in nonmusth periods. Musth males are largely solitary beyond ephemeral bonds to females for reproductive purposes. Dominance relationships were found to shape home range use and resulting movements during ecologically constrained periods, with dominant individuals accessing preferred habitats and moving less than subordinate individuals. Home ranges vary in relation to ecological conditions and individual factors. The largest home ranges, over than 30,000 km?, were found in xeric Mali, and the smallest, less than 50 km?, in more mesic Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. Ranges within a single population can vary by an order of magnitude. Males on average have larger ranges than females, but variability and maximum and minimum home range sizes do not differ much between sexes. Daily movements tend to be around 5-13 km in xeric savanna ecosystems, with most populations moving less during the dry season (though this varies). During musth, males range farther than in non-musth periods, with daily movements of 10-17 km.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I except populations of Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, which are included in Appendix II. African elephants, assessed as a single species by IUCN, are currently classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The total continental population stands between 472,269 and 689,671, with the majority of these individuals inhabiting savanna ecosystems. Less than 30% of the continent’s elephants are found in Central Africa, where the range of African Forest Elephants is predominant. Differences in the conservation status of African Savanna Elephant populations across Africa have resulted in regionally split listings by both IUCN and CITES. Currently, East African elephants, having declined by over 25% in the last three decades,are listed as Vulnerable. Central African elephants (both Forest and Savanna) are listed as Endangered. West African elephants are listed as Vulnerable, numbering less than 10,000 adults. Southern African elephants are listed as Least Concern, having increased in the last three decades. Ivory poaching and illegal ivory trade are primary threats to elephants in East, Central, and West Africa and increasingly in southern Africa. Range restriction and habitat loss are primary threats in East, West, and Southern Africa and some regions of Central Africa. Increasing human—elephant conflict is also a major threat to the species where range restriction and habitat loss are placing elephants in greater contact with humans. Approximately one third of elephant range is protected. Known range state extinctions occurred in Burundi in the 1970s, Gambia in 1913, Mauritania in the 1980s, and Swaziland in 1920 (though subsequent reintroductions in the 1980s and 1990s have returned Swaziland’s range state status). Very recent known extinctions have occurred in Sierra Leone (2010), and elephants are possibly locally extinct in Guinea Bissau and Senegal. Currently, the African elephant Specialist Group recognizes 36 range states.

Bibliography. Archie, Morrison et al. (2006), Archie, Moss, et al. (2006), Bates et al. (2008), Blanc et al. (2007), Caughley (1976), Cerling, Wittemyer, Ehleringer et al. (2009), Cerling, Wittemyer, Rasmussen et al. (2006), Douglas-Hamilton (1972), Douglas-Hamilton & Douglas-Hamilton (1975), Dublin et al. (1990), Eggert et al. (2008), Foley (2002), Hodges (1998), Laws (1970), Laws et al. (1975), Lee & Moss (1986), McComb, Moss, Durant et al. (2001), McComb, Moss, Sayialel & Baker (2000), McComb, Reby et al. (2003), Moss (1983, 1988, 2001), Murphy et al. (2001) O'Connell-Rodwell (2007), Owen-Smith (1988), Perry (1953), Poole (1989), Rasmussen et al. (2005), Roca et al. (2001), Shoshani (1998), Shoshani & Tassy (2005), Shoshani et al. (2006), Wittemyer, Douglas-Hamilton & Getz (2005), Wittemyer, Getz et al. (2007), Wittemyer, Okello et al. (2009), Wittemyer, Rasmussen & Douglas-Hamilton (2007).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Loxodonta africana

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Elephas africanus

| Blumenbach 1797 |